Abstract

Background and purpose Limb lengthening is performed for a diverse range of orthopedic problems. A high rate of complications has been reported in these patients, which include motor and sensory loss as a result of nerve damage. We investigated the effect of limb lengthening on peripheral nerve function.

Patients and methods 36 patients underwent electrophysiological testing at 3 points: (1) preoperatively, (2) after application of external fixator/corticotomy but before lengthening, and (3) after lengthening. The limb-length discrepancy was due to a congenital etiology (n = 19), a growth disturbance (n = 9), or a traumatic etiology (n = 8).

Results 2 of the traumatic etiology patients had significant changes evident on electrophysiological testing preoperatively. They both deteriorated further with lengthening. 7 of the 21 patients studied showed deterioration in nerve function after lengthening, but not postoperatively, indicating that this was due to the lengthening process and not to the surgical procedure. All of these patients had a congenital etiology for their leg-length discrepancy.

Interpretation As detailed electrophysiological tests were carried out before surgery, after surgery but before lengthening, and finally after completion of lengthening, it was possible to distinguish between the effects of the operation and the effects of lengthening on nerve function. The results indicate that the etiology, site (femur or tibia), and nerve (common peroneal or tibial) had a bearing on the risk of nerve injury and that these factors had a far greater effect than the total amount of lengthening.

Limb lengthening is carried out to correct a diverse range of orthopedic problems including post-traumatic shortening, congenital deformity, and short stature. Leg lengthening is most commonly performed using the Ilizarov method with a latency period of 5–7 days before gradual distraction with the external fixator begins (Ilizarov Citation1989b). The generation of bone, muscle, and skin during lengthening is well reported (Austad et al. Citation1982, Ilizarov Citation1989a,Citationb, Simpson et al. Citation1995). The response of peripheral nervous tissue to lengthening is less well understood, however.

It has been suggested that in response to gradual lengthening, Schwann cells synthesise new myelin and new axoplasm is formed (Hara et al. Citation2003). However, a deterioration of nerve function as a consequence of elongation has been reported in an rabbit model (Chuang et al. Citation1995) and morphological changes have been seen in a rodent model at rates of lengthening of 1.6% per day (Abe et al. Citation2004). Altered expression of sodium channels in the nodes of Ranvier following nerve elongation has also been reported, which could account for the electrophysiological changes observed in the rodent model (Ichimura et al. Citation2005).

Muscle weakness that could be due to either nerve damage or muscle damage has been reported after limb lengthening (Maffuli and Fixsen Citation1995). To determine the extent of nerve damage, a small number of studies have involved electrophysiological tests on limb-lengthening patients (Galardi et al. Citation1990, Young et al. Citation1993, Polo et al. Citation1997, Citation1999, Malliopoulos et al. Citation2007); however, since nerve testing was not carried out after application of the external fixator and corticotomy but before lengthening, it was not possible to determine how much of the nerve damage was a result of the lengthening process itself and how much was due to the operative procedure (i.e. application of fixator and corticotomy). Nogueira et al. (Citation2003) found that 16% of the nerve lesions in their patients occurred immediately after surgery.

The aim of this study was to determine whether particular kinds of patients and particular nerves were at risk of nerve dysfunction as a result of lengthening, by analyzing how nerve conduction changed at the different stages of the limb-lengthening procedure (i.e. after corticotomy but before lengthening or after lengthening) in patients with different pathologies. From this, we hoped to make recommendations for management.

Patients and methods

Study group

Over a 4-year period, electrophysiological data were collected on 36 consecutive patients over the age of 8 years who underwent leg lengthening by the Ilizarov method. Of these 19 patients had a limb-length inequality as a consequence of a congenital limb abnormality (the congenital group). 9 patients had a limb-length inequality as a result of growth disturbance due to physeal injury or childhood osteomyelitis (the growth-disturbance group). 8 patients had a leg-length discrepancy acquired after skeletal maturity due to trauma (the trauma group). 19 patients underwent unilateral tibial lengthening, (14 in the congenital group, 3 in the growth-disturbance group, and 2 in the trauma group), 11 patients underwent unilateral femoral lengthening (2 in the congenital group, 3 in the growth-disturbance group, and 6 in the trauma group), and 5 underwent both unilateral tibial and femoral lengthening (3 in the congenital group and 2 in the growth-disturbance group). 1 patient in the growth-disturbance group underwent bilateral femoral lengthening.

In all patients, leg-length inequality was corrected by distraction osteogenesis using an external fixator. At surgery, the femur or the tibia was divided percutaneously and the external frame applied. After a delay of 7 days, lengthening was started at a maximum rate of 1 mm per day, in increments of 0.25 mm. If there was evidence of poor regenerate formation or contractures of adjacent joints due to muscle tightness, the rate was reduced. The period of treatment was dependent on the amount of lengthening; the mean lengthening index was 0.9 mm/day.

Electrophysiological recordings

In patients undergoing tibial lengthening, motor nerve function was monitored by recording compound muscle action potentials (CMAPs) of a distal muscle (extensor digitorum brevis) using a Medelec Mystro 20, by placing recording electrodes over the muscle belly. The common peroneal nerve was stimulated supramaximally at the fibular head and also at the level of the ankle. The distance between the 2 stimulation points divided by the difference in the time taken from stimulation to generation of the CMAP at the 2 sites was the conduction velocity.

As the sciatic nerve could not be easily stimulated proximal to the femoral lengthening site, patients undergoing femoral lengthening were monitored using F-waves. These were generated by stimulating the tibial nerve just posterior to the medial malleolus. F-waves were generated by applying supramaximal stimulation above the distal portion of a nerve so that the impulse travelled both distally (orthodromically) and proximally (antidromically) up the axon of the motor neuron to its cell body in the spinal cord. There, a small proportion of motor neurons back-fired, generating nerve action potentials which travelled orthodromically and evoked an action potential in a small proportion of the muscle fibers—causing a small, second CMAP called the F-wave. The time from stimulation to the beginning of the muscle action potential as a result of direct orthodromic stimulation is called the distal motor latency. The time taken for the action potential to travel from the medial malleolus, antidromically up the axon to the cell body, and then back down to the motor end-plate plus the time for the beginning of the muscle action potential to be detected is called the F-wave latency. Damage to approximately 90% of the fibers can cause the F-wave to disappear.

Additional recordings were made on a subset of tibial-lengthening patients using F-waves to monitor function of the tibial and common peroneal nerves to establish whether the common peroneal nerve was more sensitive to damage than the tibial nerve.

Amplitude ratios

The amplitude of the CMAP obtained from the distal stimulation point was divided by the amplitude obtained from the proximal stimulation point and referred to as the amplitude ratio.

Statistics

All data were analyzed using Minitab release 16 (Minitab Inc., State college, Pennsylvania). CMAP and F-wave readings were not normally distributed and are therefore reported as medians with interquartile ranges. Changes in CMAP and F-wave readings between time points were normally distributed, and are reported as mean (SD). Between-group differences were assessed by the Kruskal-Wallis test or chi-square test for non-parametric data, and normally distributed data were assessed with one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA); post hoc evaluations were performed with Tukey’s HSD test to assess individual comparisons. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Electrophysiology

The change in measurement of an individual patient’s conduction velocity at the 3 different time points in the unoperated contralateral limb varied from 0.4% to 11%. We therefore considered only changes of more than 12% to be of clinical relevance. The median conduction velocities were within normal ranges at all 3 time points in the congenital and growth-disturbance groups (). The results for the trauma group (n = 8) were skewed by 2 patients. Both patients had changes in conduction velocity preoperatively—before either corticotomy or any lengthening—that were 37% and 24% less than their uninjured limbs. The former patient deteriorated further after operation and the latter patient deteriorated after lengthening. Both patients had clinically evident common peroneal nerve palsy (one postoperatively and one after lengthening).

Table 1. Conduction velocity in m/s by etiology

There was no statistically significant difference in median preoperative conduction velocity between groups (Kruskal-Wallis, p = 0.2). The F-wave latencies were similar at baseline and at later time points ().

Table 2. Latencies of F-waves in milliseconds by etiology a

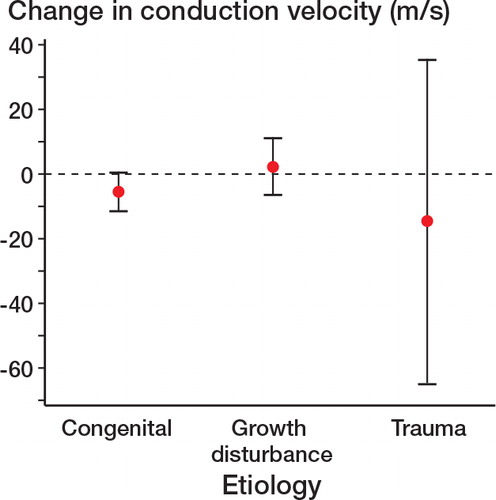

Despite the large changes in conduction velocity (particularly within the trauma group), differences between the change in mean conduction velocity between etiologies did not reach statistical significance between preoperatively and postoperatively (one-way ANOVA, F = 1.54, p = 0.3) ().

An abnormal conduction velocity preoperatively and postoperatively was observed in some patients in the trauma etiology group (). No change in conduction velocity was observed following operation in the congenital and growth-disturbance groups (). The patients undergoing tibial lengthening in these 2 groups were therefore analyzed further to assess whether there was a change in conduction velocity with lengthening. Patients with a congenital etiology showed a greater reduction in nerve function than those with growth disturbance (chi-squared, p = 0.03) ().

Table 3. Patients with and without a 12% drop (considered to be a clinically relevant change) in nerve function for different etiologies. A significantly greater risk of nerve dysfunction was observed in patients with a congenital etiology (chi-square, p = 0.03)

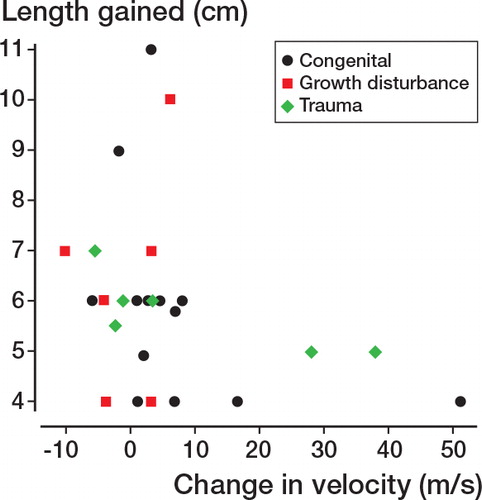

The amount of lengthening achieved was also significantly different between groups (one-way ANOVA, F = 5.31, p = 0.009). Post hoc Tukey HSD tests showed that the length achieved was greater in the growth-disturbance group at the 0.05 significance level; all other comparisons were not statistically significant. Interestingly, the lengthening achieved was not related to poor outcome either between preoperative and postoperative assessments (one-way ANOVA, F = 0.3, p = 0.9) or between postoperative and post-lengthening assessments (one-way ANOVA, F = 0.2, p = 1.0) ().

Figure 2. Length gained and change in conduction velocity after lengthening. Large changes in conduction velocity (in 2 trauma cases and 1 congenital case) are indicative of poor outcome, as these reflect poor postoperative conduction. There was no association between these cases and amount of lengthening.

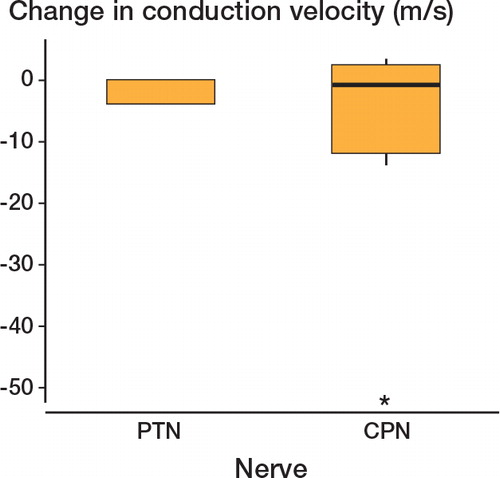

All the cases in which major disturbance to nerve conduction velocity (and function) was evident occurred when lengthening the tibia; no cases of femoral lengthening showed a reduction in conduction velocity. This included the patients undergoing simultaneous ipsilateral femoral and tibial lengthening, none of whom had a drop in conduction. In all cases of reduced conduction velocity, the common peroneal nerve was damaged ().

Amplitude ratios

Prior to surgery, CMAPs recorded from extensor digitorum brevis or abductor hallucis and the amplitude ratios were all within the normal range (78–100%), except for the 2 patients in the trauma group, who also had reduced conduction velocities. Postoperatively in the congenital group, there were no significant changes in amplitude ratio from baseline. After lengthening, the CMAPs of 5 patients in the congenital group fell to below 1mV, an order of magnitude lower than baseline readings (i.e. stimulating the nerve proximal to the site of lengthening produced a muscle action potential of low amplitude compared to the muscle action potential produced when the nerve was stimulated beyond the lengthening site). In the growth-disturbance group, there were no significant changes in amplitude ratio between preoperative and postoperative recordings, and no deterioration between postoperative and post-lengthening recordings. In the trauma group, 6 of the 8 patients were undergoing femoral lengthening, so amplitude ratios could not be measured. Of the 2 who could be measured, 1 showed complete peroneal nerve palsy postoperatively; this patient had a very low CMAP preoperatively (300 μV). The other patient also had a very weak CMAP preoperatively. These were the same patients who had low conduction velocities preoperatively. CMAPs in the other patients measured in this group were normal.

Clinical outcome

Preoperatively, 34 patients (all in the congenital and growth-disturbance groups and 6 of 8 in the trauma group) presented with no clinical signs of nerve dysfunction. 2 trauma patients whose conduction velocity was noted to be abnormal at baseline also had abnormal clinical signs: 1 patient who had loss of the anterior compartment musculature and skin had weakness of dorsiflexion and altered sensation over part of the dorsum of the foot; the other patient had normal sensation to light touch and slight weakness, which was attributed to muscle wasting while in a plaster cast. Postoperatively, no patients in the growth-disturbance group had clinically apparent nerve dysfunction. 2 patients in the congenital group had numbness on the dorsum of the foot and weakness of great toe extension. The nerve dysfunction recovered slowly in the year following the end of lengthening. The 2 patients in the trauma group with common peroneal nerve dysfunction recovered partially, but had some persisting weakness of toe dorsiflexion and altered sensation on the dorsum of the foot.

Discussion

In experimental models of limb lengthening, conflicting results have been reported on the effect of the procedure on peripheral nerves. Gil-Albarova et al. (Citation1997) did not find any changes in nerve morphology or function in a study of lengthening of lamb femurs. Similar findings have been reported by Simpson et al. (Citation2013) during lengthening of rabbit tibias. In contrast, Ippolito et al. (Citation1994) found degenerative changes in the myelin sheaths of the palmar nerves of calves, which became progressively more severe with greater amounts of lengthening.Nerve dysfunction was also observed by Shibukawa and Shirai (Citation2001) in their study of rabbit sciatic nerves; they found that with gradual elongation, the compound muscle action potential (CMAP) was reduced and the latency (i.e. the time between stimulation of the nerve and the onset of the muscle action potential) was increased. Other studies have also shown nerve dysfunction, which was more evident at rates of lengthening greater than 1 mm/day (Huang and Chang Citation1997, Skoulis et al. Citation1998, Ikeda et al. Citation2000, Yokota et al. Citation2003).

Clinically evident nerve palsy has been reported in one tenth of patients following leg-lengthening procedures (Velazquez et al. Citation1993). In the present study we found that 7 of 36 patients had electrophysiological evidence of nerve dysfunction. This could be accounted for by differences in the case mix or by differences in the technique used, but is more likely to be explained by the nerve dysfunction not being detectable clinically in half of those with neurophysiological signs of dysfunction. Malliopoulos et al. (Citation2007) reported a higher rate of electrophysiological deterioration: 8 out of 25. Galardi et al. (Citation1990) demonstrated denervation in all 10 limbs of 5 achondroplastic patients who underwent a large amount (27%) of tibial lengthening bilaterally, raising the possibility that the nerve dysfunction secondary to lengthening may be dependent on the total amount of lengthening as well as on the rate of lengthening. However, in our patients we did not find any association between the amount of lengthening and nerve dysfunction, and this concurs with a study of lengthening in short-stature patients and with the findings of Nogueira et al. (Citation2003). The latter authors found a higher risk of nerve injury in patients undergoing double-level tibial lengthening. In these patients, the nerves would have been lengthening at a faster rate. This is in agreement with reports of nerve dysfunction at rates of lengthening of more than 1.5% per day (Simpson and Kenwright Citation1997). This also suggests that patients whose nerves are tethered by scarring are at increased risk of nerve palsy, as lengthening would occur over a shorter segment of nerve.

We found a greater number of patients with dysfunction in the peroneal nerve (n = 5) than in the tibial nerve (n = 0). A greater susceptibility of the common peroneal nerve is supported by a study by Huang and Chang (Citation1997), who observed in a rabbit model that common peroneal nerve damage occurred earlier and was more severe than in the posterior tibial nerve. Our results agree with those of Young et al. (Citation1993), who demonstrated that following tibial lengthening, all 6 patients examined electrophysiologically had abnormal peroneal nerves whereas only 2 had changes in the posterior tibial nerve. Our findings are also in agreement with the results of Polo et al. (Citation1997), who reported that 4 of 14 patients undergoing lengthening for short stature showed weakness of foot dorsiflexion and electrophysiological changes, consistent with peroneal nerve damage.

The hypothesis that disruption of nerve function is greater in the common peroneal nerve (CPN) than in the posterior tibial nerve (PTN) is supported by Ikeda et al. (Citation2001), who suggested that elongated nerves are more vulnerable to compression injury. During lengthening, the common peroneal nerve and the tibial nerve are both elongated but only the common peroneal nerve is subjected to compression (against the fibula neck). Wexler et al. (Citation1998) pointed out that structured electrophysiological monitoring following limb lengthening allows early detection of nerve injuries and enables surgical intervention before nerve damage becomes permanent. In patients undergoing lengthening in whom significant compression of the common peroneal nerve against the fibula neck may be expected, it would be prudent to carry out monitoring of the nerve, perhaps by non-invasive methods such as reported by Nogueira et al. (Citation2003). If deterioration in function is observed, which does not resolve, decompression of the common peroneal nerve at the fibula neck is recommended.

In conclusion, as detailed electrophysiological tests were carried out before surgery, after surgery but before lengthening, and finally after completion of lengthening, it was possible to distinguish between the effects of the operation and the effects of lengthening on nerve function. The results suggest that (1) patients undergoing lengthening for a congenital etiology (as opposed to an acquired growth disturbance)—especially of the tibia—are at greater risk of nerve damage, and (2) that the common peroneal nerve is at greater risk of damage than the posterior tibial nerve. These factors had a greater impact than the total amount of lengthening. In addition, we found that a quarter of the patients (2 of 8) in the trauma group had electrophysiologically evident nerve dysfunction at baseline that was not evident clinically at that stage. These nerves appeared to be particularly sensitive and deteriorated further postoperatively or after lengthening.

HS: study design, review of literature, collection and analysis of data, and writing of manuscript. JH: review of literature and writing of paper. DH: analysis of data and writing of paper. MS: analysis of data. KM: collection of data and writing of paper.

We thank Dr M MacDougall for statistical advice and Professor John Kenwright for his comments on the manuscript.

No competing interests declared.

- Abe I, Ochiai N, Ichimura H, Tsujino A, Sun J, Hara Y. Internodes can nearly double in length with gradual elongation of the adult rat sciatic nerve. J Orthop Res 2004; 22: 571-7.

- Austad ED, Pasyk KA, McClatchey KD, Cherry GW. Histomorphologic evaluation of guinea pig skin and soft tissue after controlled tissue expansion. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1982; 70 (6): 704-10.

- Chuang TY, Chan RC, Chin LS, Hsu TC. Neuromuscular injury during limb lengthening: a longitudinal follow-up by rabbit tibial model. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1995; 76 (5): 467-70.

- Galardi G, Comi G, Lozza L, Marchettini P, Novarina M, Facchini R, et al.. Peripheral nerve damage during limb lengthening. Neurophysiology in five cases of bilateral tibial lengthening. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1990; 72 (1): 121-4.

- Gil-Albarova J, Melgosa M, Gil-Albarova O, Canadell J. Soft tissue behavior during limb lengthening: an experimental study in lambs. J Pediatr Orthop B 1997; 6 (4): 266-73.

- Hara Y, Shiga T, Abe I, Tsujino A, Ichimura H, Okado N, et al.. P0 mRNA expression increases during gradual nerve elongation in adult rats. Exp Neurol 2003; 184 (1): 428-35.

- Huang SC, Chang CW. Electrophysiologic evaluation of neuromuscular functions during limb lengthening by callus distraction. J Formos Med Assoc 1997; 96 (3): 172-8.

- Ichimura H, Shiga T, Abe I, Hara Y, Terui N, Tsujino A, et al.. Distribution of sodium channels during nerve elongation in rat peripheral nerve. J Orthop Sci 2005; 10 (2): 214-20.

- Ikeda K, Tomita K, Tanaka S. Experimental study of peripheral nerve injury during gradual limb elongation. Hand Surg 2000; 5 (1): 41-7.

- Ikeda K, Yokoyama M, Tomita K, Tanaka S. Vulnerability of the gradually elongated nerve to compression injury. Hand Surg 2001; 6 (1): 29-35.

- Ilizarov GA. The tension-stress effect on the genesis and growth of tissues. Part I. The influence of stability of fixation and soft-tissue preservation. Clin Orthop 1989a; (238): 249-81.

- Ilizarov GA. The tension-stress effect on the genesis and growth of tissues. Part II. The influence of the rate and frequency of distraction. Clin Orthop 1989b; (239): 263-85.

- Ippolito E, Peretti G, Bellocci M, Farsetti P, Tudisco C, Caterini R, et al.. Histology and ultrastructure of arteries, veins, and peripheral nerves during limb lengthening. Clin Orthop 1994; (308): 54-62.

- Maffuli N, Fixsen JA. Muscular strength after callotasis limb lengthening. J Pediatr Orthop 1995; 15 (2): 212-6.

- Malliopoulos X, Maisonneuve B, Fron D, Herbaux B. Electrophysical surveillance in limb lengthening in 25 children and adolescents. Ann Readapt Med Phys 2007; 50 (5): 302-5.

- Nogueira MP, Paley D, Bhave A, Herbert A, Nocente C, Herzenberg JE. Nerve lesions associated with limb-lengthening. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2003; 85 (8): 1502-10.

- Polo A, Aldegheri R, Zambito A, Trivella G, Manganotti P, De Grandis D, et al.. Lower-limb lengthening in short stature. An electrophysiological and clinical assessment of peripheral nerve function. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1997; 79 (6): 1014-8.

- Polo A, Zambito A, Aldegheri R, Tinazzi M, Rizzuto N. Nerve conduction changes during lower limb lengthening. Somatosensory evoked potentials (SEPs) and F-wave results. Electromyogr Clin Neurophysiol 1999; 39 (3): 139-44.

- Shibukawa M, Shirai Y. Experimental study on slow-speed elongation injury of the peripheral nerve: electrophysiological and histological changes. J Orthop Sci 2001; 6 (3): 262-8.

- Simpson A H R W Williams PE, Kyberd P, Goldspink G, Kenwright J. The response of muscle to leg lengthening. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1995; 77 (4): 630-6.

- Simpson A H RW, Kenwright J. Response of peripheral nerve to lengthening. Trans Orthop Res Soc 1997; 22 (1): 268.

- Simpson AH, Gillingwater TH, Anderson H, Cottrell D, Sherman DL, Ribchester RR, Brophy PJ. Effect of limb lengthening on internodal lengthand conduction velocity of peripheral nerve. J Neurosci 2013; 33 (10): 4536-9.

- Skoulis TG, Vekris MD, Terzis JK. Effect of distraction osteogenesis on the peripheral nerve: experimental study in the rat. J Reconstr Microsurg 1998; 14 (8): 565-74.

- Velazquez RJ, Bell DF, Armstrong PF, Tibshirani R. Complications of use of the Ilizarov technique in the correction of limb deformities in children. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1993; 75 (8): 1148-56.

- Wexler I, Paley D, Herzenberg JE, Herbert A. Detection of nerve entrapment during limb lengthening by means of near-nerve recording. Electromyogr Clin Neurophysiol 1998; 38 (3): 161-7.

- Yokota A, Doi M, Ohtsuka H, Abe M. Nerve conduction and microanatomy in the rabbit sciatic nerve after gradual limb lengthening-distraction neurogenesis. J Orthop Res 2003; 21 (1): 36-43.

- Young NL, Davis RJ, Bell DF, Redmond DM. Electromyographic and nerve conduction changes after tibial lengthening by the Ilizarov method. J Pediatr Orthop 1993; 13 (4): 473-7.