Abstract

Background and purpose Fungal prosthetic joint infections are rare and difficult to treat. This systematic review was conducted to determine outcome and to give treatment recommendations.

Patients and methods After an extensive search of the literature, 164 patients treated for fungal hip or knee prosthetic joint infection (PJI) were reviewed. This included 8 patients from our own institutions.

Results Most patients presented with pain (78%) and swelling (65%). In 68% of the patients, 1 or more risk factors for fungal PJI were found. In 51% of the patients, radiographs showed signs of loosening of the arthroplasty. Candida species were cultured from most patients (88%). In 21% of all patients, fungal culture results were first considered to be contamination. There was co-infection with bacteria in 33% of the patients. For outcome analysis, 119 patients had an adequate follow-up of at least 2 years. Staged revision was the treatment performed most often, with the highest success rate (85%).

Interpretation Fungal PJI resembles chronic bacterial PJI. For diagnosis, multiple samples and prolonged culturing are essential. Fungal species should be considered to be pathogens. Co-infection with bacteria should be treated with additional antibacterial agents.

We found no evidence that 1-stage revision, debridement, antibiotics, irrigation, and retention (DAIR) or antifungal therapy without surgical treatment adequately controls fungal PJI. Thus, staged revision should be the standard treatment for fungal PJI. After resection of the prosthesis, we recommend systemic antifungal treatment for at least 6 weeks—and until there are no clinical signs of infection and blood infection markers have normalized. Then reimplantation can be performed.

Prosthetic joint infection (PJI) is the most debilitating and expensive complication following arthroplasty (Bozic and Ries Citation2005). A nationwide study performed in the USA showed an infection burden of 1.23% for THA and 1.21% for TKA, with an almost 2-fold increase between 1990 and 2004 (Kurtz et al. Citation2008).

Fungal PJI is uncommon, and occurs in approximately 1% of all PJIs (Phelan et al. Citation2002, Azzam et al. Citation2009). There are few reports in the literature and most of them have included only a small number of patients (Azzam et al. Citation2009, Dutronc et al. Citation2010, Anagnostakos et al. Citation2012, Hwang et al. Citation2012). Most fungal PJIs are caused by Candida albicans and Candida parapsilosis (Azzam et al. Citation2009). Extensive comorbidity and decreased immunity are considered risk factors for fungal infections (Phelan et al. Citation2002, Azzam et al. Citation2009). The surgical treatment options are similar to those for bacterial PJIs (Azzam et al. Citation2009). The Infectious Diseases Society of America recommends removal of the arthroplasty in most patients, with therapy for at least 6 weeks with fluconazole or amphotericin B (Osmon et al. Citation2013). If removal of the arthroplasty is not an option, for instance due to the poor health of the patient, chronic suppression with fluconazole is recommended (Pappas et al. 2009).

This review covers 156 previously reported cases of fungal hip and knee PJI and 8 patients from our own institutions. We have analyzed treatment options and outcome.

Patients and methods

The following online databases were searched: Medline (period 1966 to July 2012), Cochrane Clinical Trial Register (1988 to July 2012), and Embase (January 1988 to July 2012). The search was performed independently by 2 reviewers (JK and SC). Disagreement was resolved by consensus and third party adjudication.

Using the search terms “prosthesis implantation[Mesh]” AND “candida[Mesh]”, “(candida OR fungal) AND (((hip OR knee) AND prosthesis) OR arthroplasty)”, “(candida OR fungal) AND (prosthesis OR arthroplasty) NOT medline[sb]”, we initially found 1,411 articles. The titles, abstracts, and keywords of these papers were reviewed and the full publications were retrieved if there was insufficient information to determine appropriateness for inclusion. All publications considered relevant were read completely. In addition, reference lists of publications included were checked for articles that had been missed initially. Articles that were not in English were included if translation was possible.

We also retrospectively studied patient files from all patients who had been treated for fungal PJI at our institutions between 2003 and 2011.

Data collected from all the articles included and from patients from our own institutions included: age, sex, affected joint, primary or revision surgery, comorbidity, preoperative diagnosis, symptoms, duration of symptoms, interval between primary surgery and onset of symptoms of infection, species isolated, origin of culture samples (i.e. aspiration, intraoperative, other), other microorganisms cultured, fungal culture considered irrelevant (yes or no), C-reactive protein (CRP, mg/L) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR, mm/h) at presentation, radiographic findings, local and systemic antimicrobial therapy, duration of antimicrobial therapy, type of surgical treatment, time from resection to reimplantation, outcome, and duration of follow-up.

Definitions

Risk factor status was based on risk factors previously mentioned by others: an immunosuppressive or immunodeficient status, diabetes mellitus, rheumatoid arthritis, a history of renal insufficiency, malignancy or previous PJI (Azzam et al. Citation2009, Dutronc et al. Citation2010, Kelesidis and Tsiodras Citation2010, Garcia-Oltra et al. Citation2011, Wu and Hsu Citation2011, Anagnostakos et al. Citation2012, Chiu et al. Citation2013).

Since criteria used to define infection were not always clearly noted by other authors, we decided to consider all fungal infections described in the individual studies as definite fungal infections.

Cure of fungal PJI was defined as good clinical function and absence of infectious signs and symptoms, with the arthroplasty present (either after staged revision or after debridement), without the use of chronic antifungal or antibacterial therapy and with a follow-up of at least 2 years.

Baseline data, such as patient characteristics and culture results, are not only described for patients with a follow-up of at least 2 years, but for all the patients included.

Studies included

68 studies describing fungal hip and knee PJI were found. 2 of 10 patients were excluded in a group of fungal PJI patients because the infected joint was unclear (Garcia-Oltra et al. Citation2011). From 1 study, 4 of 6 patients were excluded, as fungal native joint infection before arthroplasty was proven or strongly suspected (Kuberski et al. Citation2011). 1 article described 10 patients, 6 of which had already been reported (Phelan et al. Citation2002). In total, 64 studies were included, describing 156 patients (Table 1, see supplementary data). We included 8 more patients from our own institutions (Table 2, see supplementary data), giving a total of 164 patients.

Results

Patient characteristics

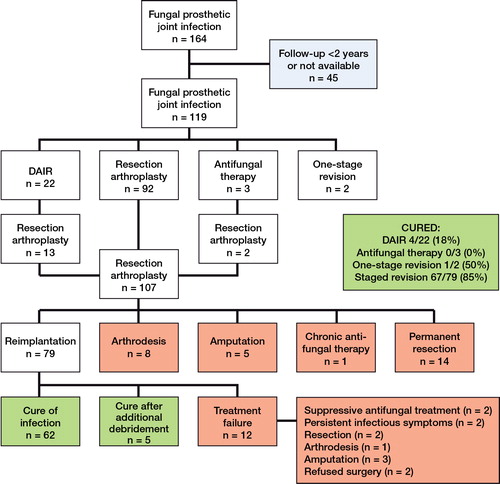

164 patients were included (63% female). 94 patients had a fungal infection of a knee arthroplasty and 70 had a fungal infection of a hip arthroplasty. Infection occurred after primary arthroplasty in 68 patients, after revision arthroplasty in 53 patients, and in 43 patients primary or revision arthroplasty was not specified. In 17 patients, the duration of follow-up was not reported, and in 32 patients follow-up was less than 2 years, leaving 119 patients with a follow-up of at least 2 years (Figure).

Flow chart describing the outcome of surgical treatment in 119 patients with fungal hip or knee PJI and with an adequate follow-up.

Possible risk factors predisposing for PJI were accurately described in 148 patients: 101 patients had 1 or more risk factors for PJI (68%) ().

Table 3. Numbers of patients with risk factors for fungal PJI, described in 148 patients with fungal PJI

Clinical features and diagnosis

Clinical symptoms were described for 147 patients. Most patients presented with symptoms of chronic infection such as pain (78%) and swelling (65%). Other symptoms included warmth (18%), limited range of motion (10%), redness (8%), and fever (7%). Wound drainage and sinus tract were described in 4% and 9% of patients, respectively.

The mean duration from last performed arthroplasty (primary or revision) to diagnosis of fungal PJI was 27 months (range 2 weeks to 22 years). 29% of the patients had an infection-free period of at least 2 years after the index surgery.

Plain radiography results were described in 118 patients. In 60 patients, signs of loosening of the prosthesis were seen (“loosening”, “lucency”, and “osteolysis”).

Blood levels of CRP (in mg/L) and ESR (in mm/h) were available in 91 and 101 patients, respectively. In 4 reports, the unit of CRP blood levels was not mentioned, and these were left out (some authors reported in mg/L and others in mg/dL). Mean CRP levels at presentation were 44 (0.9–280) mg/L; mean ESR was 53 (7–141) mm/h.

The final diagnosis was always based on culture results, from aspiration fluid alone (n = 32), intraoperative specimens alone (n = 45), or aspiration and intraoperative specimens combined (n = 32). In 3 patients, the microorganism was detected intraoperatively and with another method (1 blood culture, 1 wound drainage, 1 sinus tract).

For 51% of the patients (n = 84), it was reported whether or not the initial fungal cultures were considered to be contaminants. For 18 patients (21%), the fungal cultures were initially considered contamination.

Microbiology

Most fungal PJIs were caused by candida species (n = 145; 88%), the commonest being Candida albicans (n = 78; 48%). Other candida species were C. parapsilosis (n = 40), C. glabrata (n = 14), C. tropicalis (n = 6), C. pelliculosa (n = 3), C. lipolytica, C. guillermondii, C. famata, and C. lusitaniae (all n = 1). 5 patients had polyfungal infections, all caused by candida. Other fungal species were found in 24 patients and included species such as Aspergillus fumigatus, Pichia anomala, and Rhodotorula minuta.

In 54 patients, bacteria were also cultured (33%). Coagulase-negative Staphylococcus was cultured in 26 patients, methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) in 13 patients and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in 7 patients.

Surgical treatment

The numbers of patients in the different treatment groups are shown in the Figure. Staged revision was successful in most patients (85%). Debridement, antibiotics (antifungals), irrigation, and retention of the prosthesis (DAIR) was successful in 4 of 22 patients, one-stage revision in 1 of 2 patients, and antifungal treatment without surgery in 0 of 3 patients. The mean interval between resection and reimplantation was 4.8 months, ranging from 1 week to 1.5 years. In 55 patients with staged revision, interval duration and treatment outcome were both described, of which only 3 patients in whom treatment failed (mean interval for success 4.2 months vs. 2.8 months for failure). Interval duration of 6 weeks or less was described for 5 patients (all healed), 2 months or less for 19 patients (all healed), and 3 months or less for 34 patients (32 healed).

The use of a spacer was described in 86 patients. 68 spacers were loaded with antibiotic agents, 5 with antifungal agents, and 7 with both. The exact doses of antifungal agents were mentioned by 7 authors. Antifungal drugs used were amphotericin B in 9 patients (between 187.5 mg and 1,200 mg per batch of bone cement (40 g), amphotericin B and variconazole in 1 patient (250 mg and 1,000 mg per batch, respectively), fluconazole in 1 patient (200 mg in a spacer), and itraconazole in 1 patient (250 mg in a spacer). In 2 patients, fluconazole-loaded bone cement beads were implanted (2,000 mg per batch of bone cement).

Antifungal therapy

160 of 164 patients were treated with systemic antifungal agents, mostly with amphotericin B (71 patients) or fluconazole (80 patients). A combination of both was used in 4 patients. All fluconazole use was described in studies after 1996 (70/80 patients between 2002 and 2012). Amphotericin B was more frequently used in earlier studies (44/71 patients between 2002 and 2012). The use of echinocandins, a new group of antifungal agents, was described in 6 patients (2005–2012): caspofungin in 3, micafungin in 2, and anidafungin in 1.

In 143 patients, the total duration of antifungal treatment was mentioned (intravenous and oral combined), with a mean of 3.8 (0–36) months. 7 other patients received chronic antifungal therapy at follow-up.

54 patients who underwent a staged revision had a follow-up of more than 2 years and an adequate description of antifungal treatment duration; 48 of them were treated successfully. Failures (n = 6) had antifungal therapy for a mean of 5.7 (2.5–12) months. Successfully treated patients were given antifungal agents for a shorter period (mean 2.9 months).

Antifungal agent administration of 0–6 weeks was described in 13 patients (n = 13), with success in all. 0–2 months was reported in 28 patients, who all healed. 0–3 months was described in 40 patients (38 of whom healed), and 0–6 months in 48 patients (44 of whom healed).

Discussion

Risk factors

Risk factors usually associated with fungal infections, more specifically with candidiasis, are mostly factors related to comorbidity with an impaired immune response: an immunosuppressive or immunodeficient status, diabetes mellitus, rheumatoid arthritis, malignancy, tuberculosis, and/or a history of renal transplantation or insufficiency (Azzam et al. Citation2009, Kelesidis and Tsiodras Citation2010, Anagnostakos et al. Citation2012). Other, external factors include drug abuse, prolonged antibiotic use, in-dwelling catheters, malnutrition, severe burns, and multiple abdominal surgeries (Azzam et al. Citation2009, Kelesidis and Tsiodras Citation2010, Anagnostakos et al. Citation2012). These factors are also assumed to play a role in fungal prosthetic joint infection. Other predominant factors include previous PJI, revision surgery, and cutaneous candidiasis (Azzam et al. Citation2009, Dutronc et al. Citation2010, Kelesidis and Tsiodras Citation2010, Garcia-Oltra et al. Citation2011, Wu and Hsu Citation2011, Anagnostakos et al. Citation2012, Chiu et al. Citation2013). Azzam et al. (Citation2009) showed that around 50% of patients with fungal PJI had 1 or more risk factors, including cardiac disease. However, we found that 101 of 148 patients had one or more risk factors for fungal PJI (68% of the patients), not including cardiac disease as a risk factor. When we included cardiac disease, 82% of the patients were at risk (122/148).

Clinical features and diagnosis

The route of infection for fungal PJI remains controversial. The mechanism and clinical features often mimic that of chronic bacterial infection, with an indolent onset, and most often patients present with swelling and pain without other symptoms of infection (Darouiche et al. Citation1989, Lerch et al. Citation2003, Azzam et al. Citation2009, Dutronc et al. Citation2010, Chiu et al. Citation2013). Prosthetic loosening is seen in many patients, as the infection may have been lingering for years (Lambertus et al. Citation1988, Brooks and Pupparo Citation1998). We found that half of the patients had radiographic signs of loosening. This is comparable to patients with bacterial PJIs (Bernard et al. Citation2004). As fungal PJI develops slowly, diagnosis is difficult, and the diagnosis ‘aseptic loosening’ is easily made—especially with no bacterial co-infection (Lerch et al. Citation2003).

Most authors agree that serum values, such as CRP and ESR, and joint fluid cell counts have limited value. Discrimination between fungal and bacterial PJI is impossible based on laboratory values. The value of additional tests such as bone scintigraphy and serum titers remains unclear (Paul et al. Citation1992, Kelesidis and Tsiodras Citation2010, Anagnostakos et al. Citation2012).

The diagnosis should be based on cultures from aspiration fluid or tissue or swabs obtained at surgery. However, a substantial delay in diagnosis may occur because culture results are sometimes interpreted as contamination, and most authors recommend obtaining multiple samples, prolonged culture, and special staining (Ramamohan et al. Citation2001, Yang et al. Citation2001, Azzam et al. Citation2009, Dutronc et al. Citation2010, Chiu et al. Citation2013). Furthermore, according to Dutronc et al. (Citation2010), if candida species are cultured, they should always be treated as a pathogen. We found that in 21% of the patients, the fungal culture result was—incorrectly—considered to be contamination. We recommend that a cultured fungal species should always be considered to be a pathogen.

Because diagnosis with the above-mentioned microbiological methods may be difficult, other methods such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) may be useful. However, none of the articles on fungal PJI mentioned PCR.

Treatment

Primary antifungal drug treatment, without surgical treatment, was described in only 3 patients with adequate follow-up, none of which healed. DAIR was successful in 4 of 22 patients. For bacterial PJI, the consensus is that chronic infections should never be treated with DAIR (Crockarell et al. Citation1998, Osmon et al. Citation2013). We suggest the same for fungal PJI.

1-stage revision, performed in 2 patients, was successful in 1 patient and unsuccessful in the other (Simonian et al. Citation1997, Selmon et al. Citation1998). These numbers are too small to draw any conclusions about 1-stage revision as an alternative to 2-stage revision for fungal PJI.

Many authors have treated fungal PJI as a chronic bacterial infection, and staged revision is generally recommended (Darouiche et al. Citation1989, Lerch et al. Citation2003, Azzam et al. Citation2009, Dutronc et al. Citation2010, Chiu et al. Citation2013). In our series, this treatment was commonest, with a success rate of 85% (67/79 patients). The success rate of staged revisions for bacterial PJIs is approximately 87–91% (Garvin and Hanssen 1995, Sia et al. Citation2005,van Diemen et al. Citation2013).

The ideal interval between implant removal and reimplantation is unknown. We found a mean of 4.8 months, with a range from 1 week to 1.5 years. Some authors have suggested a 3-month period (Evans and Nelson Citation1990, Yang et al. Citation2001) whereas others have advised reimplantation only when repeated (aspiration) cultures are negative (Phelan et al. Citation2002, Chiu et al. Citation2013). The time between resection and reimplantation arthroplasty was mentioned for only 3 patients with failure of staged revision (mean 2.8 months as opposed to 4.2 months in the successfully treated patients). The group of patients in which the interval was adequately mentioned may not have been representative for the whole group of fungal PJI patients. Apart from a minimum of 6 weeks, we do not dare to make recommendations on the duration of the resection reimplantation interval. We therefore recommend that reimplantation should be performed only in the absence of clinical signs of infectious symptoms, with CRP and ESR serum levels within the normal range (CRP < 5.0 mg/L and ESR < 10 mm/h) or showing continuously falling values.

The use of local antifungal treatment was described in 14 patients (2 beads, 12 spacers) (Selmon et al. Citation1998, Bruce et al. Citation2001, Marra et al. Citation2001, Phelan et al. Citation2002, Gaston and Ogden Citation2004, Gottesman-Yekutieli et al. Citation2011, Wu and Hsu Citation2011, Deelstra et al. Citation2013). 2 groups reported high local levels of antifungal agent with this method (Bruce et al. Citation2001, Marra et al. Citation2001), but others claimed that local antifungal therapy had no effect, based on laboratory studies (Wyman et al. Citation2002, Azzam et al. Citation2009). An antibiotic-loaded spacer to treat bacterial co-infection or prevent bacterial superinfection was used in 75 patients (Azzam et al. Citation2009, Anagnostakos et al. Citation2012, Deelstra et al. Citation2013). No specific recommendations about the use of antifungal treatment in cement can be made because of the low number of patients. However, adding antibiotics to the cement is advisable because of the high number of patients with a combined fungal and bacterial PJI (33%).

Antifungal therapy

Most authors suggested a minimum duration of treatment of 6 weeks (Ramamohan et al. Citation2001, Phelan et al. Citation2002, Anagnostakos et al. Citation2012), but others advised a minimum of 12 months (Azzam et al. Citation2009, Austen et al. Citation2013). Amphotericin B or fluconazole have been considered the drugs of choice for administration in fungal infections (Gaston and Ogden Citation2004, Antony et al. Citation2008, Austen et al. Citation2013). All fluconazole treatments were described in studies reported after 1996. This can be explained by the time of development of the products, and by the publication of studies that indicate that fluconazole is as effective for hematogenous candidiasis yet better tolerated than amphotericin B (Rex et al. 1994). Amphotericin B is one of the most toxic antimicrobial drugs, with a high incidence of adverse effects (Merrer et al. Citation2001). On the other hand, primary resistance against fluconazole is common in some non-albicans candida species, particularly Candida krusei and Candida glabrata (Selmon et al. Citation1998, Kontoyiannis and Lewis Citation2002).

The use of echocandins was only described in a few reports (Lejko-Zupanc et al. Citation2005, Dumaine et al. Citation2008, Bland and Thomas Citation2009, Graw et al. Citation2010), but it may be a good alternative—due to its low toxicity and broad spectrum—especially for fluconazole-resistant fungal species, or if amphotericin B is not tolerated by the patient. However, the long-term side effects are unclear (Kelesidis and Tsiodras Citation2010).

The period of antifungal treatment was shorter in successfully treated patients than in patients with treatment failure. This might be due to several factors, including selection bias (e.g. patients in a worse condition may be treated longer) and publication bias (e.g. patients cured with a short antifungal period may be more interesting to publish). Longer treatment may be bothersome for some patients. We concur with other authors, and because duration (comparing 6 weeks and 3 months of antifungal treatment) does not appear to influence outcome after reimplantation, we recommend antifungal treatment for at least 6 weeks, which may be extended until serum CRP and ESR levels have normalized or show continuously falling values, and clinical signs of infection remain absent. There is no evidence that a shorter period of antifungal treatment will give the same results.

Conclusion

68% of the patients with fungal PJI had 1 or more risk factors predisposing for fungal PJI. The majority of these patients presented with signs and symptoms similar to those of chronic bacterial PJIs, such as pain, swelling, and prosthetic loosening. The diagnostic tools are the same for both kinds of infection, as recommended by the Workgroup of the Musculoskeletal Infection Society (Parvizi et al. Citation2011). Cultured fungi, including candida species, should be considered pathogenic. In the future, DNA techniques such as PCR could assist in the diagnosis, and might even prove to be more accurate than culture (Osmon et al. Citation2013).

Based on our findings, we recommend 2-stage revision for all patients with a fungal PJI. There is no evidence that 1-stage revision, DAIR, or only antifungal therapy have similar results. Based on our findings, we recommend giving systemic antifungal treatment at least until there are no clinical signs of infectious symptoms, with normalized infection parameters in blood. After that, reimplantation can be considered or performed. There is insufficient evidence that the use of local antifungal treatment has additional benefits. Systemic and local antibacterial drugs should be added (to the cement) when there is co-infection with bacteria.

www.actaorthop.org

Download PDF (35.4 KB)JK, MB, and SC conceived and designed the study. JK and SC performed the literature search. JK, SC, and JS analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to interpretation of the data and revision of the final manuscript.

No competing interests declared.

- Acikgoz ZC, Sayli U, Avci S, Dogruel H, Gamberzade S. An extremely uncommon infection: Candida glabrata arthritis after total knee arthroplasty. Scand J Infect Dis 2002; 34 (5): 394-6.

- Anagnostakos K, Kelm J, Schmitt E, Jung J. Fungal periprosthetic hip and knee joint infections clinical experience with a 2-stage treatment protocol. J Arthroplasty 2012; 27 (2): 293-8.

- Antony S, Dominguez DC, Jackson J, Misenheimer G. Evaluation and treatment of candida species in prosthetic joint infections. Infect Dis Clin Pract 2008; 16: 354-9.

- Austen S, van der Weegen W, Verduin CM, van d, V, Hoekstra HJ. Coccidioidomycosis infection of a total knee arthroplasty in a nonendemic region. J Arthroplasty 2013; 28 (2): 375.

- Austin KS, Testa NN, Luntz RK, Greene JB, Smiles S. Aspergillus infection of total knee arthroplasty presenting as a popliteal cyst. Case report and review of the literature. J Arthroplasty 1992; 7 (3): 311-4.

- Azzam K, Parvizi J, Jungkind D, Hanssen A, Fehring T, Springer B, Bozic K, Della VC, Pulido L, Barrack R. Microbiological, clinical, and surgical features of fungal prosthetic joint infections: a multi-institutional experience. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) (Suppl 6) 2009; 91: 142-9.

- Badrul B, Ruslan G. Candida albicans infection of a prosthetic knee replacement: a case report. Med J Malaysia (Suppl C) 2000; 55: 93-6.

- Baumann PA, Cunningham B, Patel NS, Finn HA. Aspergillus fumigatus infection in a mega prosthetic total knee arthroplasty: salvage by staged reimplantation with 5-year follow-up. J Arthroplasty 2001; 16 (4): 498-503.

- Bernard L, Lubbeke A, Stern R, Bru JP, Feron JM, Peyramond D, Denormandie P, Arvieux C, Chirouze C, Perronne C, Hoffmeyer P. Value of preoperative investigations in diagnosing prosthetic joint infection: retrospective cohort study and literature review. Scand J Infect Dis 2004; 36 (6-7): 410-6.

- Bland CM, Thomas S. Micafungin plus fluconazole in an infected knee with retained hardware due to Candida albicans. Ann Pharmacother 2009; 43 (3): 528-31.

- Bozic KJ, Ries MD. The impact of infection after total hip arthroplasty on hospital and surgeon resource utilization. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2005; 87 (8): 1746-51.

- Brooks DH, Pupparo F. Successful salvage of a primary total knee arthroplasty infected with Candida parapsilosis. J Arthroplasty 1998; 13 (6): 707-12.

- Bruce AS, Kerry RM, Norman P, Stockley I. Fluconazole-impregnated beads in the management of fungal infection of prosthetic joints. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2001; 83 (2): 183-4.

- Cardinal E, Braunstein EM, Capello WN, Heck DA. Candida albicans infection of prosthetic joints. Orthopedics 1996; 19 (3): 247-51.

- Chiu W-K, Chung K-Y, Cheung K-W, Chiu K-H. Candida parapsilosis total hip arthroplasty infection: case report and literature review. J Orthop Trauma 2013; 17: 33-6.

- Crockarell JR, Hanssen AD, Osmon DR, Morrey BF. Treatment of infection with debridement and retention of the components following hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1998; 80 (9): 1306-13.

- Cushing RD, Fulgenzi WR. Synovial fluid levels of fluconazole in a patient with Candida parapsilosis prosthetic joint infection who had an excellent clinical response. J Arthroplasty 1997; 12 (8): 950.

- Cutrona AF, Shah M, Himes MS, Miladore MA. Rhodotorula minuta: an unusual fungal infection in hip-joint prosthesis. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 2002; 31 (3): 137-40.

- Darouiche RO, Hamill RJ, Musher DM, Young EJ, Harris RL. Periprosthetic candidal infections following arthroplasty. Rev Infect Dis 1989; 11 (1): 89-96.

- Deelstra JJ, Neut D, Jutte PC. Successful Treatment of Candida Albicans-Infected Total Hip Prosthesis With Staged Procedure Using an Antifungal-Loaded Cement Spacer. J Arthroplasty 2013; 28 (2): 374.

- DeHart DJ. Use of itraconazole for treatment of sporotrichosis involving a knee prosthesis. Clin Infect Dis 1995; 21 (2): 450.

- Del Pozo JL, Patel R. Clinical practice. Infection associated with prosthetic joints. N Engl J Med 2009; 361 (8): 787-94.

- Dumaine V, Eyrolle L, Baixench MT, Paugam A, Larousserie F, Padoin C, Tod M, Salmon D. Successful treatment of prosthetic knee Candida glabrata infection with caspofungin combined with flucytosine. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2008; 31 (4): 398-9.

- Dutronc H, Dauchy FA, Cazanave C, Rougie C, Lafarie-Castet S, Couprie B, Fabre T, Dupon M. Candida prosthetic infections: case series and literature review. Scand J Infect Dis 2010; 42 (11-12): 890-5.

- Esposito S, Leone S. Prosthetic joint infections: microbiology, diagnosis, management and prevention. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2008; 32 (4): 287-93.

- Evans RP, Nelson CL. Staged reimplantation of a total hip prosthesis after infection with Candida albicans. A report of two cases. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1990; 72 (10): 1551-3.

- Fabry K, Verheyden F, Nelen G. Infection of a total knee prosthesis by Candida glabrata: a case report. Acta Orthop Belg 2005; 71 (1): 119-21.

- Fevang BT, Lie SA, Havelin LI, Engesaeter LB, Furnes O. Improved results of primary total hip replacement. Acta Orthop 2010; 81 (6): 649-59.

- Fowler VG, Jr., Nacinovich FM, Alspaugh JA, Corey GR. Prosthetic joint infection due to Histoplasma capsulatum: case report and review. Clin Infect Dis 1998; 26 (4): 1017.

- Fukasawa N, Shirakura K. Candida arthritis after total knee arthroplasty—a case of successful treatment without prosthesis removal. Acta Orthop Scand 1997; 68 (3): 306-7.

- Garcia-Oltra E, Garcia-Ramiro S, Martinez JC, Tibau R, Bori G, Bosch J, Mensa J, Soriano A. Prosthetic joint infection by Candida spp. Rev Esp Quimioter 2011; 24 (1): 37-41.

- Garvin KL, Hanssen AD. Infection after total hip arthroplasty. Past, present, and future. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1995; 77 (10): 1576-88.

- Gaston G, Ogden J. Candida glabrata periprosthetic infection: a case report and literature review. J Arthroplasty 2004; 19 (7): 927-30.

- Giulieri SG, Graber P, Ochsner PE, Zimmerli W. Management of infection associated with total hip arthroplasty according to a treatment algorithm. Infection 2004; 32 (4): 222-8.

- Goodman JS, Seibert DG, Reahl GE, Jr., Geckler RW. Fungal infection of prosthetic joints: a report of two cases. J Rheumatol 1983; 10 (3): 494-5.

- Gottesman-Yekutieli T, Shwartz O, Edelman A, Hendel D, Dan M. Pseudallescheria boydii infection of a prosthetic hip joint—an uncommon infection in a rare location. Am J Med Sci 2011; 342 (3): 250-3.

- Graw B, Woolson S, Huddleston JI. Candida infection in total knee arthroplasty with successful reimplantation. J Knee Surg 2010; 23 (3): 169-74.

- Guyard M, Vaz G, Aleksic I, Guyen O, Carret JP, Bejui-Hugues J. Aspergillar prosthetic hip infection with false aneurysm of the common femoral artery and cup migration into the pelvis. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot 2006; 92 (6): 606-9.

- Hennessy MJ. Infection of a total knee arthroplasty by Candida parapsilosis. A case report of successful treatment by joint reimplantation with a literature review. Am J Knee Surg 1996; 9 (3): 133-6.

- Hwang BH, Yoon JY, Nam CH, Jung KA, Lee SC, Han CD, Moon SH. Fungal peri-prosthetic joint infection after primary total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2012; 94 (5): 656-9.

- Iskander MK, Khan MA. Candida albicans infection of a prosthetic knee replacement. J Rheumatol 1988; 15 (10): 1594-5.

- Johannsson B, Callaghan JJ. Prosthetic hip infection due to Cryptococcus neoformans: case report. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2009; 64 (1): 76-9.

- Kelesidis T, Tsiodras S. Candida albicans prosthetic hip infection in elderly patients: is fluconazole monotherapy an option? Scand J Infect Dis 2010; 42 (1): 12-21.

- Koch AE. Candida albicans infection of a prosthetic knee replacement: a report and review of the literature. J Rheumatol 1988; 15 (2): 362-5.

- Kontoyiannis DP, Lewis RE. Antifungal drug resistance of pathogenic fungi. Lancet 2002; 359 (9312): 1135-44.

- Kuberski T, Ianas V, Ferguson T, Nomura J, Johnson R. Treatment of prosthetic joint infections associated with coccidioidomycosis. Infect Dis Clin Pract 2011; (19): 252-5.

- Kurtz SM, Lau E, Schmier J, Ong KL, Zhao K, Parvizi J. Infection burden for hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States. J Arthroplasty 2008; 23 (7): 984-91.

- Lackner M, De Man FH, Eygendaal D, Wintermans RG, Kluytmans JA, Klaassen CH, Meis JF. Severe prosthetic joint infection in an immunocompetent male patient due to a therapy refractory Pseudallescheria apiosperma. Mycoses (Suppl 3) 2011; 54: 22-7.

- Lambertus M, Thordarson D, Goetz MB. Fungal prosthetic arthritis: presentation of two cases and review of the literature. Rev Infect Dis 1988; 10 (5): 1038-43.

- Langer P, Kassim RA, Macari GS, Saleh KJ. Aspergillus infection after total knee arthroplasty. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 2003; 32 (8): 402-4.

- Lazzarini L, Manfrin V, De LF. Candidal prosthetic hip infection in a patient with previous candidal septic arthritis. J Arthroplasty 2004; 19 (2): 248-52.

- Lejko-Zupanc T, Mozina E, Vrevc F. Caspofungin as treatment for Candida glabrata hip infection. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2005; 25 (3): 273-4.

- Lerch K, Kalteis T, Schubert T, Lehn N, Grifka J. Prosthetic joint infections with osteomyelitis due to Candida albicans. Mycoses 2003; 46 (11-12): 462-6.

- Levine M, Rehm SJ, Wilde AH. Infection with Candida albicans of a total knee arthroplasty. Case report and review of the literature. Clin Orthop 1988; (226): 235-9.

- MacGregor RR, Schimmer BM, Steinberg ME. Results of combined amphotericin B-5-fluorcytosine therapy for prosthetic knee joint infected with Candida parapsilosis. J Rheumatol 1979; 6 (4): 451-5.

- Marra F, Robbins GM, Masri BA, Duncan C, Wasan KM, Kwong EH, Jewesson PJ. Amphotericin B-loaded bone cement to treat osteomyelitis caused by Candida albicans. Can J Surg 2001; 44 (5): 383-6.

- Merrer J, Dupont B, Nieszkowska A, De JB, Outin H. Candida albicans prosthetic arthritis treated with fluconazole alone. J Infect 2001; 42 (3): 208-9.

- Moisés J, Calls J, Ara J, Pérez L, Coll E, García S, Bergadá E, López-Pedret J, Revert L, Darnell A. Candida parapsilosis sepsis in a patient on maintenance hemodialysis with a hip-joint replacement. Nefrologia 1998; 18 (4): 330-2.

- Nayeri F, Cameron R, Chryssanthou E, Johansson L, Soderstrom C. Candida glabrata prosthesis infection following pyelonephritis and septicaemia. Scand J Infect Dis 1997; 29 (6): 635-8.

- Osmon DR, Berbari EF, Berendt AR, Lew D, Zimmerli W, Steckelberg JM, Rao N, Hanssen A, Wilson WR. Diagnosis and management of prosthetic joint infection: clinical practice guidelines by the infectious diseases society of america. Clin Infect Dis 2013; 56 (1): e1-e25.

- Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes D, Benjamin DK, Jr., Calandra TF, Edwards JE, Jr., Filler SG, Fisher JF, Kullberg BJ, Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Reboli AC, Rex JH, Walsh TJ, Sobel JD. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of candidiasis: 2009 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2009; 48 (5): 503-35.

- Parvizi J, Zmistowski B, Berbari EF, Bauer TW, Springer BD, Della Valle CJ, Garvin KL, Mont MA, Wongworawat MD, Zalavras CG. New definition for periprosthetic joint infection: from the Workgroup of the Musculoskeletal Infection Society. Clin Orthop 2011; (469) (11): 2992-4.

- Paul J, White SH, Nicholls KM, Crook DW. Prosthetic joint infection due to Candida parapsilosis in the UK: case report and literature review. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 1992; 11 (9): 847-9.

- Phelan DM, Osmon DR, Keating MR, Hanssen AD. Delayed reimplantation arthroplasty for candidal prosthetic joint infection: a report of 4 cases and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis 2002; 34 (7): 930-8.

- Prenzel KL, Isenberg J, Helling HJ, Rehm KE. Candida infection in hip alloarthroplasty. Unfallchirurg 2003; 106 (1): 70-2.

- Ramamohan N, Zeineh N, Grigoris P, Butcher I. Candida glabrata infection after total hip arthroplasty. J Infect 2001; 42 (1): 74-6.

- Rex J H, Bennett J E, Sugar A M, Pappas P G, van der Horst C M, Edwards J E, Washburn R G, Scheld W M, Karchmer A W, Dine A P. A randomized trial comparing fluconazole with amphotericin B for the treatment of candidemia in patients without neutropenia. Candidemia Study Group and the National Institute. N Engl J Med 1994; 331 (20): 1325-30.

- Selmon GP, Slater RN, Shepperd JA, Wright EP. Successful 1-stage exchange total knee arthroplasty for fungal infection. J Arthroplasty 1998; 13 (1): 114-5.

- Sia IG, Berbari EF, Karchmer AW. Prosthetic joint infections. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2005; 19 (4): 885-914.

- Simonian PT, Brause BD, Wickiewicz TL. Candida infection after total knee arthroplasty. Management without resection or amphotericin B. J Arthroplasty 1997; 12 (7): 825-9.

- Tunkel AR, Thomas CY, Wispelwey B. Candida prosthetic arthritis: report of a case treated with fluconazole and review of the literature. Am J Med 1993; 94 (1): 100-3.

- van Diemen MP, Colen S, Dalemans AA, Stuyck J, Mulier M. Two-stage revision of an infected total hip arthroplasty: a follow-up of 136 patients. Hip Int 2013; 17: 0. Epub ahead of print.

- Villamil-Cajoto I, Van der Eynde-Collado A, Otero LR, Villacian Vicedo MJ. Personal autonomy in the management of candidal prosthetic joint infection. Cent Eur J Med 2012; 7 (4): 539-41.

- Wada M, Baba H, Imura S. Prosthetic knee Candida parapsilosis infection. J Arthroplasty 1998; 13 (4): 479-82.

- White A, Goetz MB. Candida parapsilosis prosthetic joint infection unresponsive to treatment with fluconazole. Clin Infect Dis 1995; 20 (4): 1068-9.

- Wu MH, Hsu KY. Candidal arthritis in revision knee arthroplasty successfully treated with sequential parenteral-oral fluconazole and amphotericin B-loaded cement spacer. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2011; 19 (2): 273-6.

- Wyman J, McGough R, Limbird R. Fungal infection of a total knee prosthesis: successful treatment using articulating cement spacers and staged reimplantation. Orthopedics 2002; 25 (12): 1391-4.

- Yang SH, Pao JL, Hang YS. Staged reimplantation of total knee arthroplasty after Candida infection. J Arthroplasty 2001; 16 (4): 529-32.

- Yilmaz M, Mete B, Ozaras R, Kaynak G, Tabak F, Tenekecioglu Y, Ozturk R. Aspergillus fumigatus infection as a delayed manifestation of prosthetic knee arthroplasty and a review of the literature. Scand J Infect Dis 2011; 43 (8): 573-8.

- Younkin S, Evarts CM, Steigbigel RT. Candida parapsilosis infection of a total hip-joint replacement: successful reimplantation after treatment with amphotericin B and 5-fluorocytosine. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1984; 66 (1): 142-3.