Abstract

Background and purpose — There are very few data concerning the outcome after short-segment posterior stabilization and anterior spondylodesis with rib grafts in patients suffering from unstable thoracolumbar burst fractures. We have therefore investigated the clinical and radiographic outcome after posterior bisegmental instrumentation and monosegmental anterior spondylodesis using an autologous rib graft for unstable thoracolumbar burst fractures.

Patients and methods — This was a retrospective analysis of 32 consecutive patients at a single center. The monosegmental Cobb angle was measured preoperatively, postoperatively, then 6 and 12 months postoperatively, and also after implant removal. Anterior vertebral fusion was graded on conventional radiographs according to the criteria proposed by Molinari.

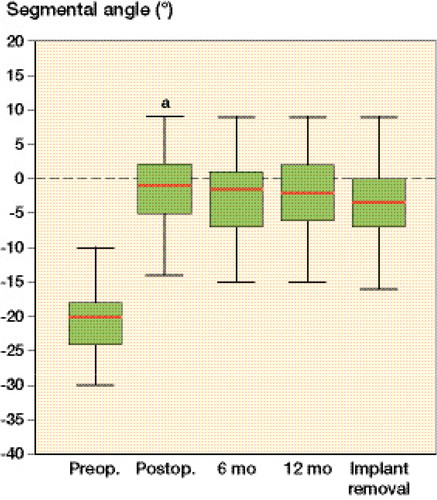

Results — Segmental kyphosis at the fracture site was corrected from a median of -20° (95% CI: -21.2 to -18.8) to -1.0° (95% CI: -2.7 to 0.7) postoperatively. 1 year after surgery, the segmental angle had decreased by a median of 2.0° (95% CI: 0.2 to 2.8). The spondylodesis fused in all patients, which was evident from incorporation and remodeling of the rib grafts. The median correction loss after implant removal was 0.0° (95% CI: -0.5 to 0.5). 26 of the 32 patients reported having no back complaints at the last follow-up (2 years postoperatively). 1 patient suffered from intercostal neuralgia, and 5 patients reported mild to moderate back pain.

Interpretation — Short-segment posterior instrumentation and anterior spondylodesis using an autologous rib graft resulted in sufficient correction of posttraumatic segmental kyphosis. There was no clinically relevant correction loss, and the majority of patients had no back complaints at the 2-year follow-up.

Thoracolumbar (T11–L2) burst fractures that are unstable (i.e. failure of the anterior and middle column under compression or disruption of the posterior column) or associated with a neurologic deficit are most often treated surgically (Verlaan et al. Citation2004, Oner et al. Citation2010). Currently, short-segment posterior stabilization is considered to be the first step towards preserving motion segments, preventing adjacent segment disease, shortening operating time, and reducing intraoperative blood loss (Verlaan et al. Citation2004, Dai et al. Citation2007, Zdeblick et al. Citation2009, Gelb et al. Citation2010, Kim et al. Citation2011, Schmid et al. Citation2011, Tofuku et al. Citation2012). Furthermore, short-segment posterior stabilization can be performed in a standard emergency surgery setting. However, there has been some controversy concerning the need and type of anterior treatment. Combined posterior and anterior spondylodesis may result in better pain relief (Verlaan et al. Citation2004) and less correction loss (Bertram et al. Citation2003, Oner et al. Citation2010) or instrumentation failure (Been and Bouma Citation1999) compared to posterior surgery alone in patients suffering from burst fractures with an impaired anterior column.

Autologous bone grafting results in superior fusion rates compared to allografts (An et al. Citation1995). However, donor-site morbidity often impairs clinical outcome (Summers and Eisenstein Citation1989, Emery et al. Citation1996, Myeroff and Archdeacon Citation2011). If thoracotomy is performed to access thoracolumbar burst fractures from anterior, autologous rib grafts can be harvested without additional surgery. To date, little is known about the outcome after anterior spondylodesis with rib grafts in patients suffering from thoracolumbar burst fractures (Buhren and Braun Citation1993, Vieweg et al. Citation1996, Nakamura et al. Citation2001). We have therefore investigated the clinical and radiographic outcome after posterior bisegmental instrumentation and monosegmental spondylodesis combined with anterior monosegmental spondylodesis using an autologous rib graft for treatment of thoracolumbar burst fractures.

Patients and methods

Included in this retrospective study were 37 consecutive patients who were treated with posterior bisegmental instrumentation and monosegmental spondylodesis combined with anterior monosegmental spondylodesis using an autologous rib graft for thoracolumbar burst fractures (T11–L2) at a single institution between 1999 and 2007. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Canton Lucerne.

Indications for surgery

Indications for surgery included instability (i.e. disruption of posterior structures), neurological deficits (i.e. paraplegia), risk of spinal cord injury (e.g. retropulsed fragment, spinal canal compromise), substantial damage of the proximal intervertebral disc, or severe kyphosis (> 20°) (Argenson et al. Citation1996, Munting Citation2010). In patients without neurological deficits, MRI was used to investigate the integrity of the posterior structures.

Surgery

Surgeries were performed by 6 experienced spine surgeons. In principle, a 2-stage procedure was performed. First, posterior fracture reduction, restoration of the sagittal plane alignment, and stabilization using an internal fixator with monoaxial screws (Universal Spine System or SpineFix System, Synthes, Switzerland) was achieved. Posterior instrumentation involved 2 motion segments. Autologous vertebral bone—and if necessary allologous (Tutoplast, Novomedics GmbH, Zürich, Switzerland) or xenologous bone (Tutobone, Novomedics GmbH, Zürich, Switzerland)—was used for monosegmental posterior spondylodesis. Secondly, after approximately 10 days, anterior spondylodesis was performed using a rib graft. When the respiratory and cardiovascular condition of the patient allowed, posterior and anterior procedures were performed as 1 stage.

Posterior fracture reduction, restoration of the sagittal plane alignment, and stabilization using an internal fixator with monoaxial screws was performed with the patient in prone position according to the technique described by Dick (Citation1987). A single dose (1g) of a first-generation cephalosporin was given before surgery. The fractured vertebra was identified with a fluoroscope, and a midline incision was performed over the spinous processes reaching from 1 adjacent vertebra below to 1 above. Access to the pedicles was gained by dissecting the thoracolumbar fascia and blunt detachment of the paravertebral muscles. Monoaxial pedicle screws were placed into the vertebral bodies above and below the injury (bisegmental instrumentation). Rods were cut to the appropriate length and bent in order to restore lordosis and achieve fracture reduction. In cases of persistent spinal canal compromise, laminectomy and occasionally direct repositioning of a retropulsed fragment was performed. Posterolateral spondylodesis between the injured and adjacent proximal vertebra was accomplished by decortication and adding the removed bone flakes together with allologous or xenologous bone. The wound was closed in layers and a drain was placed inside the subcutaneous tissue.

Anterior spondylodesis was performed during the same intervention, if the respiratory and cardiovascular condition of the patient allowed, or approximately 10 days after posterior surgery. Single-lumen tracheal intubation was used, and patients were placed in right lateral recumbence. The skin was incised (8-10 cm) over the rib 2 levels proximal to the injured vertebra. The periosteum was stripped from the ventral two-thirds of the rib, and the segmental nerve and blood vessels were identified. A 12- to 14-cm rib bone graft was then harvested. Subsequently, the pleura was perforated (minimized incision length of ~10 cm), and a retractor system was placed. After identification of the injured vertebra using fluoroscopy, the parietal pleura was dissected longitudinally along the vertebral bodies, reaching from the proximal adjacent vertebra to the distal adjacent vertebra. Afterwards, the proximal (injured) disc and the fractured part of the injured vertebra (partial corpectomy) were removed. Corpectomy was performed with a chisel and with a view to creating a flat and level surface. The posterior wall of the injured vertebra was spared, but thinned with rongeurs to facilitate resorption. The cartilaginous endplate of the proximal vertebra was removed completely with rasps to facilitate fusion. Afterwards, approximately 5 autologous rib strut grafts of appropriate length (2-3 cm) were inserted press-fit in the sagittal plane compactly side by side like a palisade (). Attention was paid to prepare the bone bed carefully and place the rib grafts correctly. A chest tube was placed, and the pleura was partially closed. Finally, a catheter connected to an analgesic perfusor was put into the costodiaphragmatic recess, and deep wound drainage was positioned. The wound was closed in layers. The chest tube, wound drain, and catheter were removed after 2-3 days. Patients were mobilized one day after anterior surgery. Patients without spinal cord injury wore a thoracolumbar brace for 12 weeks in order to prevent excessive inclination and reclination, because the additional anterior spondylodesis did not provide primary stability.

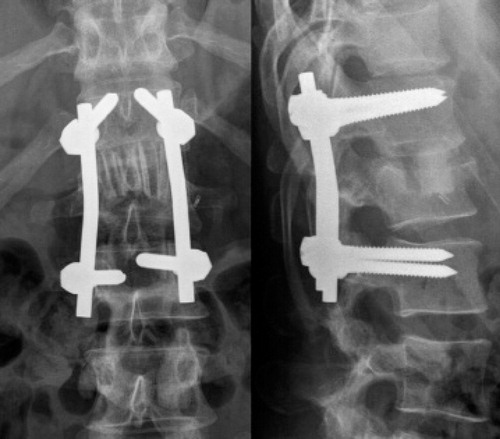

Figure 1. Anteroposterior (left) and lateral (right) view of the thoracolumbar spine (T11 to L3) on postoperative radiographs after an AO type B2.3 fracture of L1. Bisegmental posterior instrumentation from T12 to L2 and anterior spondylodesis from T12 to L1 using an autologous rib graft was performed. The image shows the rib strut grafts in situ, arranged like a palisade.

Implant removal

Removal of the implants was recommended after fusion had occurred, in order to restore motion to the additionally fixed superior motion segment.

Follow-up

Clinical and conventional radiographic evaluation took place after 1, 6, and 12 weeks; 6 and 12 months postoperatively; and 6 and 12 months after implant removal. Postoperative pain was assessed on a numeric rating scale (NRS) from 0 to 10 (mild pain: 1–4; moderate pain: 5–7; severe pain: 8–10). Postoperative computed tomography (CT) imaging was only performed if indicated by findings on the conventional radiographs, or if patients reported moderate or severe back pain.

Radiographic analysis

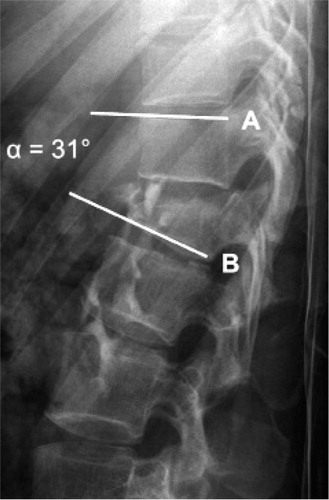

Fractures were graded according to the AO classification system using preoperative conventional radiographs and CT images (Magerl et al. Citation1994). The monosegmental Cobb angle (Keynan et al. Citation2006) () between the lower endplate of the fractured vertebra and the upper endplate of the adjacent proximal vertebra was measured on lateral conventional radiographs using Phoenix PACS software (version 3.20.34233; Phoenix-PACS GmbH, Freiburg, Germany). Negative values indicate kyphotic angles and positive values indicate lordotic angles. Anterior interbody fusion was graded according to Molinari et al. (Citation1999) as follows. Grade I: fused with remodeling and trabeculae present; grade II: graft intact, not fully remodeled and incorporated, and no lucency present; grade III: graft intact, potential lucency present at the top or bottom of the graft; grade IV: fusion absent with collapse/resorption of the graft.

Figure 2. Lateral view of the thoracolumbar spine on a conventional radiograph after an AO type B1.2 fracture of L1. The segmental angle (α) was determined by measuring the angle between the line (B) parallel to the lower endplate of the fractured vertebra and the line (A) parallel to the upper endplate of the adjacent proximal vertebra (Keynan et al. Citation2006).

Statistics

Data are presented as median, range, and 95% confidence interval (CI). Differences between the monosegmental Cobb angles were tested using the Friedman and Wilcoxon signed rank test. In all statistical analyses, any p-value of < 0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software (version 15.0).

Results

5 of the 37 patients were lost to follow-up because they had moved abroad, and they were therefore excluded from the analysis. Thus, we analyzed the data on 32 patients (26 males) (Table). The median age at the time of injury was 31 (16–67 years). The fractures had most often occurred after falls (n = 11), followed by para-gliding (n = 8), traffic accidents (n = 6), winter sport accidents (n = 5), and other trauma (n = 2). The most frequently affected vertebrae were L1 (n = 20) and T12 (n = 10). The fracture severity according to the AO classification system was: 1 A3.1 lesion, 1 A3.2 lesion, 14 B1.2 lesions, 10 B2.3 lesions, and 6 C1.3 lesions. 5 patients had sustained additional vertebral fractures (AO type A.1). 4 patients had suffered from polytrauma (cranial, thoracic, abdominal, or pelvic injuries, long bone fractures). All the patients with neurological deficits had received methylprednisolone in different dose regimens within the first 48 h after injury. In 10 patients (including all 5 patients without neurological deficits), MRI was used to investigate the integrity of the posterior ligamentous complex. A rupture of the posterior ligamentous complex was therefore confirmed in all 5 patients without neurological deficits.

The median time from injury to surgery was 1 (0–26) days. A crosslink rod was connected in 3 patients (2 AO type B fracture and 1 type C fracture). In 3 patients, laminectomy was performed for decompression of the spinal cord. Additional allologous or xenologous bone was used for posterior spondylodesis in 3 and 5 patients. Anterior surgery was performed after a median time of 8 (0–58) days. In 10 patients, posterior and anterior surgery was carried out in a single intervention. Most commonly, anterior spondylodesis was performed with the tenth rib (n = 26). The ninth and eleventh ribs were used in 4 and 2 patients, respectively.

Individual patient characteristics, Cobb angles, and outcomes after posterior bisegmental instrumentation and monosegmental spondylodesis combined with anterior monosegmental spondylodesis using an autologous rib graft

There were no relevant perioperative complications. Furthermore, no implant failure or loosening was observed. In the majority of patients (n = 22), posterior instrumentation was removed after a median time of 19 (13–32) months. 3 patients refused implant removal, and for 6 patients there was no information available as to why the implants were not removed. 1 patient suffered from chronic intercostal neuralgia. 26 patients had no complaints concerning their back. 1 and 2 patients suffered from mild and moderate back pain after implant removal. In the 10 patients without implant removal, 2 patients reported mild back pain postoperatively.

The segmental kyphosis was corrected from a median of -20° (range: -25 to -10; CI: -21 to -19) to -1.0° (range: -14 to 8; CI: -2.7 to 0.7) postoperatively (). The segmental angle decreased by a median of 2.0° (range: -2 to 17; CI: 0.2 to 2.8) from the postoperative situation to 12 months postoperatively. The median correction loss after implant removal was 0.0° (range: -2 to 6; CI: -0.5 to 0.5). There was no statistically significant difference between the segmental angle before and after implant removal (p = 0.12).

Figure 3. Box plots of segmental angles preoperatively and postoperatively, 6 months and 12 months postoperatively, and 4.0 months (95% CI: 4.9–14.0) after implant removal, i.e. 28.0 months (95% CI: 26.2–36.7) postoperatively, and 1.5x interquartile range (whiskers). Values are median (lines), 95% CI (boxes), and range (bars). a significantly different from 6- and 12-month values (p < 0.001).

At the time of admission, 27 patients suffered from neurological deficits (Table). The patient with the AO type A2.3 fracture presented with an American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) impairment score (AIS) D, but recovered completely postoperatively (AIS E). 20 of the 24 patients with AO type B fractures showed neurological impairment. 2 patients recovered from AIS B and D, respectively, to AIS E, and 1 patient improved from AIS B to AIS D. All the patients who had sustained an AO type C fracture suffered from neurological deficits (2 patients with AIS A and 4 with AIS D), and there was no improvement in the AIS at discharge.

Anterior spondylodesis resulted in fusion in all patients, as evidenced by incorporation and remodeling of the rib grafts (). There was no lucency, collapse, or resorption of a graft. The median Molinari score 12 months postoperatively was 2 (1–3), and it was 1 (1–1) after implant removal.

Figure 4. Postoperative image after an AO type B2.3 fracture of L1. Anterior spondylodesis resulted in solid fusion 2 years postoperatively, and the posterior instrumentation was therefore removed. The autologous rib grafts were incorporated and partially remodeled. There were no signs of lucency or resorption.

Discussion

The restoration and maintenance of the anatomic alignment in the sagittal plane is an important goal in the surgical treatment of thoracolumbar burst fractures. It is important from a functional point of view (Argenson et al. Citation1996) and for prevention of accelerated disc degeneration of adjacent segments (Lee Citation1988, Kumar et al. Citation2001)—and possibly pain associated with kyphotic deformity (Malcolm et al. Citation1981, Farcy et al. Citation1990, Vaccaro and Silber Citation2001). In our series, the posttraumatic segmental angle was corrected from a median of -20° to -1° (kyphosis) postoperatively. After implant removal, the median segmental angle was -3°. In comparison, the physiological segmental angles in the thoracolumbar spine (T11–L2) range from -4.8° to -1.2° (Vialle et al. Citation2005). Correction loss 1 year postoperatively was minor and clinically irrelevant, and no further correction loss was observed thereafter until 2 years postoperatively (implants removed). These findings are in accordance with results in the literature. In systematic review and multicenter studies, the postoperative bisegmental angle has been reported to decrease by approximately 5° after combined posterior and anterior spondylodesis as compared to approximately 7° after short posterior spondylodesis (Verlaan et al. Citation2004, Reinhold et al. Citation2010). In a recent multicenter study, the authors concluded that combined posterior and anterior surgery restored posttraumatic deformity best (Reinhold et al. Citation2010). However, the clinical relevance and benefit of this small difference in kyphosis correction is questionable. The additional morbidity risks and costs with the anterior approach need to be justified by the clinical benefits. Nevertheless, there does not appear to be a relevant difference in the risk of complications after combined techniques and the risk after posterior techniques (Verlaan et al. Citation2004). Furthermore, the differences in treated patient groups or fractures and outcome measures between studies may have masked relevant differences between the techniques under investigation in published studies. Thus, randomized prospective studies comparing the different techniques are required to establish true benefits of one technique over another.

Stabilization allowing early mobilization for rehabilitation and prevention of pressure sores is particularly important in paraplegic patients. In the present study, most patients had sustained a neurological injury; 8 of 32 patients suffered from complete paraplegia. The rate of patients with neurological injury and complete paraplegia in other studies has been lower than in our study, i.e. between 5% and 25% (Reinhold et al. Citation2010, Schmid et al. Citation2011). In our experience, posterior instrumentation in the thoracic and thoracolumbar region commonly causes pressure points and discomfort in wheelchair users. Furthermore, monosegmental posterior and anterior spondylodesis is performed in order to preserve motion segments and prevent adjacent segment disease. Thus, we recommend removal of the posterior instrumentation in wheelchair users especially, but also in patients without any neurological deficits.

Postoperative neurological improvement was observed in 4 patients. 3 of these 4 patients (1 with AO type A fractures and 2 with AO type B fractures) recovered completely (AIS E). However, none of the patients with AO type C fractures showed any improvement in the AIS. The correction of the compromised spinal canal did not generally result in neurological improvement but possibly prevented further neurological deterioration. Our observations are largely in accordance with those in the literature (Verlaan et al. Citation2004, Oner et al. Citation2010, Schmid et al. Citation2010). Complete cord injury (AIS A) is not likely to resolve whereas patients with mild neurological deficits have a greater chance of recovery (Reinhold et al. Citation2010).

We did not encounter any major perioperative complications and there were no implant failures or loosening. In a systematic review of surgical treatment of thoracolumbar fractures, a complication rate of 5% was reported after anteroposterior surgery (Verlaan et al. Citation2004). Most patients (72%) were pain-free after anteroposterior surgery, 22% suffered from mild to moderate back pain, and 6% suffered from constant severe pain. In the present study, 81% reported having no back pain and 19% complained of mild to moderate back pain. Postoperative pain after thoracolumbar fractures may persist or develop because of progressive kyphosis as a result of abnormal stresses placed on the facet joints, the intervertebral discs, and the surrounding soft tissues (Malcolm et al. Citation1981, Vaccaro and Silber Citation2001, Glassman et al. Citation2005, Munting Citation2010). Furthermore, the injured intervertebral disc itself may become a source of pain if it is not removed completely, as a result of chronic osteochondrosis (Mayer and Korge Citation2002).

The additional anterior approach facilitates the complete removal of the injured intervertebral disc, and this may prevent chronic posttraumatic back pain (Willen et al. Citation1990, Benson et al. Citation1992). Furthermore, it has been suggested that postoperative kyphosis after thoracolumbar burst fractures mainly occurs because of disc height loss (Wang et al. Citation2008) resulting from a collapse of the injured disc space (Daniaux et al. Citation1991, Muller et al. Citation1999, Walchli et al. Citation2001) or creeping of the disc into the fractured bony endplate (Oner et al. Citation1998).

Some authors have claimed that the rib graft segments must be fixed together with wire, thread, or a screw to achieve sufficient mechanical stability (Vieweg et al. Citation1996). However, in our study there was no graft failure, even though the graft segments were not fixed together. 3-4 rib segments are required to attain load-carrying capacity similar to that of iliac bone grafts (Vieweg et al. Citation1996, Nakamura et al. Citation2001). The anterior approach to thoracolumbar fractures via thoracotomy facilitates the harvest of autologous rib grafts, which achieve excellent fusion rates and very little donor-site morbidity.

Other authors have also reported successful outcomes after short-segment posterior instrumentation for treatment of AO type B and C thoracolumbar burst fractures with anterior spondylodesis (Reinhold et al. Citation2010, Schmid et al. Citation2010) or without (Gelb et al. Citation2010, Reinhold et al. Citation2010). However, the degree of correction loss was great without anterior spondylodesis (Gelb et al. Citation2010, Reinhold et al. Citation2010).

One limitation of our study was the possibility of patient selection bias as a result of investigating patients who presented at our institution, which is a private rehabilitation center for spinal cord-injured patients. Furthermore, this was a retrospective study with no comparison or control group. A randomized, prospective comparison of the present technique with other standard techniques is required to ascertain and validate the current results. The quality of fusion was assessed on conventional radiographs and not on CT images, which would be considered to be the gold-standard method. As a result of the retrospective nature of our study, CT images at the time of implant removal were not available for all patients. According to common clinical practice, postoperative CT imaging was only performed if indicated by findings on the conventional radiographs, or if patients reported moderate or severe back pain (NRS 5–10).

In conclusion, there was no clinically relevant correction loss postoperatively and after implant removal, and there were no major complications. Most patients had no complaints concerning their back at the last follow-up.

Conception and design: NA and PM. Acquisition of data: TK. Analysis and interpretation of data: JK. Drafting of manuscript: NA and JK. Critical revision of manuscript and approval of final version: NA, TK, PM, and JK.

No competing interests declared.

- An HS, Simpson JM, Glover JM, Stephany J. Comparison between allograft plus demineralized bone matrix versus autograft in anterior cervical fusion. A prospective multicenter study. Spine 1995; 20 (20): 2211-6.

- Argenson C, Lassale B, Begue T, Denis F, Feron M, Guigui P, et al. Recent fractures of the thoracic and lumbar spine with or without neurologic disorders. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot (Suppl 1) 1996; 82:61-127.

- Been HD, Bouma GJ. Comparison of two types of surgery for thoraco-lumbar burst fractures: combined anterior and posterior stabilisation vs. posterior instrumentation only. Acta Neurochir 1999; 141 (4): 349-57.

- Benson DR, Burkus JK, Montesano PX, Sutherland TB, McLain RF. Unstable thoracolumbar and lumbar burst fractures treated with the AO fixateur interne. J Spinal Disord 1992; 5 (3): 335-43.

- Bertram R, Bessem H, Diedrich O, Wagner U, Schmitt O. Comparison of dorso-lateral and dorso-ventral stabilization procedures in the treatment of vertebral fractures. Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb 2003; 141 (5): 573-7.

- Buhren V, Braun C. Ventrale Fusionsosteosynthese mit Rippensegmentblock zur Behandlung von Frakturen der Brustwirbelsäule Operat Orthop Traumatol 1993; 5 (4): 245-58.

- Dai LY, Jiang SD, Wang XY, Jiang LS. A review of the management of thoracolumbar burst fractures. Surg Neurol 2007; 67 (3): 221-31.

- Daniaux H, Seykora P, Genelin A, Lang T, Kathrein A. Application of posterior plating and modifications in thoracolumbar spine injuries. Indication, techniques, and results. Spine (3 Suppl) 1991; 16: S125-33.

- Dick W. The “fixateur interne” as a versatile implant for spine surgery. Spine 1987; 12 (9): 882-900.

- Emery SE, Heller JG, Petersilge CA, Bolesta MJ, Whitesides TE, Jr. Tibial stress fracture after a graft has been obtained from the fibula. A report of five cases. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1996; 78 (8): 1248-51.

- Farcy JP, Weidenbaum M, Glassman SD. Sagittal index in management of thoracolumbar burst fractures. Spine 1990; 15 (9): 958-65.

- Gelb D, Ludwig S, Karp JE, Chung EH, Werner C, Kim T, et al. Successful treatment of thoracolumbar fractures with short-segment pedicle instrumentation. J Spinal Disord Tech 2010; 23 (5): 293-301.

- Glassman SD, Bridwell K, Dimar JR, Horton W, Berven S, Schwab F. The impact of positive sagittal balance in adult spinal deformity. Spine 2005; 30 (18): 2024-9.

- Keynan O, Fisher CG, Vaccaro A, Fehlings MG, Oner FC, Dietz J, et al. Radiographic measurement parameters in thoracolumbar fractures: a systematic review and consensus statement of the spine trauma study group. Spine 2006; 31 (5): E156-65.

- Kim YM, Kim DS, Choi ES, Shon HC, Park KJ, Cho BK, et al. Nonfusion method in thoracolumbar and lumbar spinal fractures. Spine 2011; 36 (2): 170-6.

- Kumar MN, Baklanov A, Chopin D. Correlation between sagittal plane changes and adjacent segment degeneration following lumbar spine fusion. Eur Spine J 2001; 10 (4): 314-9.

- Lee CK. Accelerated degeneration of the segment adjacent to a lumbar fusion. Spine 1988; 13 (3): 375-7.

- Magerl F, Aebi M, Gertzbein SD, Harms J, Nazarian S. A comprehensive classification of thoracic and lumbar injuries. Eur Spine J 1994; 3 (4): 184-201.

- Malcolm BW, Bradford DS, Winter RB, Chou SN. Post-traumatic kyphosis. A review of forty-eight surgically treated patients. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1981; 63 (6): 891-9.

- Mayer HM, Korge A. Non-fusion technology in degenerative lumbar spinal disorders: facts, questions, challenges. Eur Spine J (Suppl 2) 2002; 11: S85-91.

- Molinari RW, Bridwell KH, Klepps SJ, Baldus C. Minimum 5-year follow-up of anterior column structural allografts in the thoracic and lumbar spine. Spine 1999; 24 (10): 967-72.

- Muller U, Berlemann U, Sledge J, Schwarzenbach O. Treatment of thoracolumbar burst fractures without neurologic deficit by indirect reduction and posterior instrumentation: bisegmental stabilization with monosegmental fusion. Eur Spine J 1999; 8 (4): 284-9.

- Munting E. Surgical treatment of post-traumatic kyphosis in the thoracolumbar spine: indications and technical aspects. Eur Spine J (Suppl 1) 2010; 19: S69-73.

- Myeroff C, Archdeacon M. Autogenous bone graft: donor sites and techniques. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2011; 93 (23): 2227-36.

- Nakamura H, Yamano Y, Seki M, Konishi S. Use of folded vascularized rib graft in anterior fusion after treatment of thoracic and upper lumbar lesions. Technical note. J Neurosurg (2 Suppl) 2001; 94: 323-7.

- Oner FC, van der Rijt RR, Ramos LM, Dhert WJ, Verbout AJ. Changes in the disc space after fractures of the thoracolumbar spine. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1998; 80 (5): 833-9.

- Oner FC, Wood KB, Smith JS, Shaffrey CI. Therapeutic decision making in thoracolumbar spine trauma. Spine (21 Suppl) 2010; 35: S235-44.

- Reinhold M, Knop C, Beisse R, Audige L, Kandziora F, Pizanis A, et al. Operative treatment of 733 patients with acute thoracolumbar spinal injuries: comprehensive results from the second, prospective, Internet-based multicenter study of the Spine Study Group of the German Association of Trauma Surgery. Eur Spine J 2010; 19 (10): 1657-76.

- Schmid R, Krappinger D, Seykora P, Blauth M, Kathrein A. PLIF in thoracolumbar trauma: technique and radiological results. Eur Spine J 2010; 19 (7): 1079-86.

- Schmid R, Krappinger D, Blauth M, Kathrein A. Mid-term results of PLIF/TLIF in trauma. Eur Spine J 2011; 20 (3): 395-402.

- Summers BN, Eisenstein SM. Donor site pain from the ilium. A complication of lumbar spine fusion. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1989; 71 (4): 677-80.

- Tofuku K, Koga H, Ijiri K, Ishidou Y, Yamamoto T, Zenmyo M, et al. Combined posterior and delayed staged mini-open anterior short-segment fusion for thoracolumbar burst fractures. J Spinal Disord Tech 2012; 25 (1): 38-46.

- Vaccaro AR, Silber JS. Post-traumatic spinal deformity. Spine (24 Suppl) 2001; 26: S111-8.

- Verlaan JJ, Diekerhof CH, Buskens E, van der Tweel I, Verbout AJ, Dhert WJ, et al. Surgical treatment of traumatic fractures of the thoracic and lumbar spine: a systematic review of the literature on techniques, complications, and outcome. Spine 2004; 29 (7): 803-14.

- Vialle R, Levassor N, Rillardon L, Templier A, Skalli W, Guigui P. Radiographic analysis of the sagittal alignment and balance of the spine in asymptomatic subjects. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2005; 87 (2): 260-7.

- Vieweg U, Kaden B, Schramm J. Vertebral body replacement with a rib segment block in transthoracic intervention. Zentralbl Neurochir 1996; 57 (3): 136-42.

- Walchli B, Heini P, Berlemann U. Loss of correction after dorsal stabilization of burst fractures of the thoracolumbar junction. The role of transpedicular spongiosa plasty. Unfallchirurg 2001; 104 (8): 742-7.

- Wang XY, Dai LY, Xu HZ, Chi YL. Kyphosis recurrence after posterior short-segment fixation in thoracolumbar burst fractures. J Neurosurg Spine 2008; 8 (3): 246-54.

- Willen J, Anderson J, Toomoka K, Singer K. The natural history of burst fractures at the thoracolumbar junction. J Spinal Disord 1990; 3 (1): 39-46.

- Zdeblick TA, Sasso RC, Vaccaro AR, Chapman JR, Harris MB. Surgical treatment of thoracolumbar fractures. Instr Course Lect 2009; 58: 639-44.