Abstract

Background and purpose Enhanced Recovery (ER) is a well-established multidisciplinary strategy in lower limb arthroplasty and was introduced in our department in May 2008. This retrospective study reviews short-term outcomes in a consecutive unselected series of 3,000 procedures (the “ER” group), and compares them to a numerically comparable cohort that had been operated on previously using a traditional protocol (the “Trad” group).

Methods Prospectively collected data on surgical endpoints (length of stay (LOS), return to theater (RTT), re-admission, and 30- and 90-day mortality) and medical complications (stroke, gastrointestinal bleeding, myocardial infarction, and pneumonia within 30 days; deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism within 60 days) were compared.

Results ER included 1,256 THR patients and 1,744 TKR patients (1,369 THRs and 1,631 TKRs in Trad). The median LOS in the ER group was reduced (3 days vs. 6 days; p = 0.01). Blood transfusion rate was also reduced (7.6% vs. 23%; p < 0.001), as was RTT rate (p = 0.05). The 30-day incidence of myocardial infarction declined (0.4% vs. 0.9%; p = 0.03) while that of stroke, gastrointestinal bleeding, pneumonia, deep vein thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism was not statistically significantly different. Mortality at 30 days and at 90 days was 0.1% and 0.5%, respectively, as compared to 0.5% and 0.8% using the traditional protocol (p = 0.03 and p = 0.1, respectively).

Interpretation This is the largest study of ER arthroplasty, and provides safety data on a consecutive unselected series. The program has achieved a statistically significant reduction in LOS and in cardiac ischemic events for our patients, with a near-significant decrease in return to theater and in mortality rates.

Enhanced Recovery (ER) or fast-track total hip (THA) and total knee arthroplasty (TKA) has become well established (Malviya et al. Citation2011). This is a multidisciplinary strategy involving patient education, multimodal analgesia, standardized perioperative anesthesia and local anesthetic infiltration, judicious fluid administration, and early mobilization. It has been shown to reduce length of stay (LOS) without increasing re-admission rates (Husted et al. Citation2008, Citation2010b, Malviya et al. Citation2011). Other endpoints reportedly expedited or improved with fast-track programs include functional rehabilitation and patient outcome (Holm et al. Citation2010, Larsen et al. Citation2010). Medical complications including thromboembolism are not more frequent using ER techniques (Husted et al. Citation2010a).

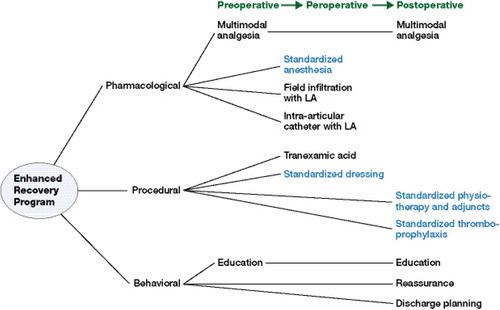

An earlier study showed reduced early mortality in the first 1,500 procedures at our unit under a locally adapted ER programme (Malviya et al. Citation2011). We wanted to determine whether the beneficial effects of ER arthroplasty would persist in a larger group of patients. We now present the short-term (90-day) outcomes and safety data for the first 3,000 unselected consecutive primary hip and knee arthroplasties performed using this ER program, which we have compared to those from an unselected consecutive series of 3,000 procedures using the traditional (Trad) protocol immediately before the introduction of the ER program. Both protocols are summarized in .

Table 1. Protocols followed during the different periods in this study. Adapted from Malviya et al. Citation2011

Methods

The ER program was started in May 2008 and all patients were operated on by 9 consultant surgeons at 2 sites within the same Trust. Only ASA grade-1 and -2 patients were operated on at site 1. Site 2 has a high-dependency facility, and patients of all ASA grades underwent procedures at this site.

The pharmacological components of the program included standardized anesthesia and pre- and postoperative analgesia. Analgesia started on the night before surgery with Gabapentin (300 mg). Low-dose spinal anesthesia was administered for each procedure, with sedation or light general anesthesia, and 1 g intravenous Paracetamol with or without 40 mg intravenous Parecoxib. Levobupivacaine (0.125%, 80 mL) was infiltrated intraoperatively in a wide and layered field including joint capsule, muscle, fat, and skin. During wound closure, an epidural catheter complete with microbiological filter was placed within the joint and tunnelled to exit away from the surgical wound. 20 mL Levobupivacaine was infused through the catheter after skin closure, and 3 postoperative boluses were delivered at 6, 14, and 24 h. THA patients received 20-mL boluses and the larger intra-articular space in TKA could accommodate 40-mL boluses (Nechleba et al. Citation2005). The ambIT pump (Summit Medical Products, Sandy, UT) was used to deliver the boluses in all these cases, and the scrub and ward nursing staff received regular scheduled sessions to train and maintain skills. Postoperative regular analgesia included Gabapentin (300 mg twice daily for 5 days) and Oxycontin (5–20 mg twice daily for 2 days) followed by Tramadol (50–100 mg every 4–6 h). All patients received intravenous Tranexamic acid (15 mg/kg) as a slow bolus at induction.

The procedural measures were introduced with the intention of reducing perioperative blood loss and to facilitate earlier mobilization. Drains were not used. Wound dressings were standardized (Abuzakuk et al. Citation2006, Clarke et al. Citation2009). TKAs also received a single-layered crepe bandage and a compressive cuff (AirCast Knee Cryo/Cuff; DJO UK Ltd., Guildford, Surrey, UK). Physiotherapy was started within 3–5 h of surgery. Staff nurses were trained to mobilize patients when physiotherapists were not available. Physiotherapy moved from 5 to 7 days a week as the program started, with each patient being reviewed once immediately after the surgery and twice on each subsequent day until discharge.

Behavioral changes were fundamental to the program. Patient education started with the initial outpatient consultation, at which mobilization and length-of-stay expectations were discussed and an information DVD was provided. The message was reiterated by different team members and all patients were invited to attend a patient education class. They were counselled that pain could be expected (Jones et al. Citation2011). The Figure illustrates the different components in relation to the patients’ progression through the ER program.

This schematic diagram shows the patient’s progression through different components of the Enhanced Recovery program.

A uniform blood transfusion policy was adopted in June 2007 (during use of the traditional approach). This is based on national guidelines and has remained unchanged during ER (Department of Health 2007). The transfusion threshold at our unit is a hemoglobin (Hb) value of 80 g/L in the typical physically well patient undergoing arthroplasty. Transfusion is administered routinely at Hb levels less than 70 g/L. For patients with cardiovascular disease, or those expected to have covert cardiovascular disease (e.g. elderly patients or those with peripheral vascular disease), transfusion is considered when the Hb value is less than 90 g/L. Supplementary oral iron is prescribed with or without laxatives if Hb is between 90 and 100 g/L. Orthogeriatric rehabilitation is done on-site, and the LOS data include the rehabilitation stay for the patients who required it. Discharge refers to discharge home. The hospital’s discharge criteria did not change with the implementation of the program. These included the patient (1) reasonably pain-free on regular analgesia, (2) voiding urine normally without a catheter, (3) ambulant with 2 crutches at the most, (4) confident alone on the stairs, and (5) able to move the knee 0–90°; with visits organized for district nurses to administer injections of low-molecular-weight heparin.

Certain components of the protocol did change during the implementation of the program. Thromboprophylaxis changed in accordance with evolving guidance from National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)

The department used aspirin and stockings until October 4, 2006 (midway in the traditional program) when it was changed to Tinzaparin (Innohep; LEO Pharma A/S, Ballerup, Denmark) (4,500 U subcutaneously, once daily). This was continued in the ER program until July 31, 2009. Rivaroxaban (Xarelto; Bayer Schering Pharma AG, Wuppertal, Germany) (10 mg orally, once daily) was used between August 1, 2009 and February 1, 2010, before finally reverting to Tinzaparin (Jensen et al. Citation2011). Preoperative Dexamethasone was part of the protocol initially but was discontinued because of concerns about potential immunosuppression. Some physical measures targeting Clostridium difficile and MRSA infections were introduced over the study period, including chlorine-containing cleaning agents in patient areas (August 2007) and the start of “Deep Clean” (January 2008) and hydrogen peroxide fumigation (June 2008). The antibiotic prophylaxis at the start of the traditional protocol was 3 doses of Cefuroxime (1.5 g, 750 mg, and 750 mg). This was changed in October 2007 to high-dose Gentamicin (4.5 mg/kg), which was continued in the ER program. It was finally changed to Gentamicin (3 mg/kg) and Teicoplanin (400 mg) in February 2009 (Sprowson et al. Citation2012). The change to Gentamicin led to concerns about renal dysfunction, and the concomitant use of non-steroidal analgesics could not be adopted as a regular feature in our ER program despite their reported benefit in improving postoperative outcomes (Aveline et al. Citation2009, Schroer et al. Citation2011). Lastly, there was a national shortage of intravenous Tranexamic acid for 18 weeks (National Electronic Library for Medicines 2010). Instead, the oral preparation was administered in 302 procedures at a dose of 25 mg/kg (maximum 2 g).

Qualified coders collected data on all patient episodes. Data on individual episodes were linked, so that complications resulting in re-admission after a successful discharge were included. By using the appropriate codes (Bramer 1988, NHS Connecting for Health 2009), complication rates after primary joint arthroplasty were identified. We report on surgical endpoints (return to theater (RTT) and re-admission) and medical complications (stroke, gastrointestinal bleeding (GIB), myocardial infarction (MI), and pneumonia within 30 days; deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE) within 60 days; and mortality at 30 and 90 days). No patients were lost to follow-up.

Statistics

The data on LOS were non-parametric, and Mann-Whitney U test was used to analyze differences between the 2 cohorts. Prevalence of comorbidities, surgical outcomes, and incidence of complications were treated as binomial variables. These were calculated as 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and they were also compared using chi-square tests (where p-values of less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant).

Results

6,000 unselected consecutive arthroplasty procedures where examined. These included 3,000 traditional procedures (in 2,639 patients) between April 2004 and April 2008 and 3,000 ER procedures (in 2,680 patients) between May 2008 and July 2011. compares the demographics and comorbidities between patient episodes in the 2 groups. The ER group had a higher proportion of females, and more patients underwent TKAs than in the Trad group. Also, a higher proportion of ER episodes were coded with hypertension (p < 0.001), type 2 diabetes (p < 0.001), and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (p = 0.002).

Table 2. A comparison of demographics and comorbidities between the two cohorts

The median LOS was reduced by 3 days in the ER group (). This reduction in hospital stay due to earlier achievement of discharge criteria did not result in a higher re-admission rate. Requirement for blood transfusion was less in the ER group (p < 0.001), as was the RTT rate (p = 0.05). In the ER group there were statistically significant reductions for 30-day incidence of MI and death. There were 5 deaths within the first 30 days in the ER group, all being in hospital. The causes were perioperative cardiac arrest (day 0), myocardial infarction (day 2), multiple organ failure secondary to pneumonia (day 3), pancreatitis (day 6), and pulmonary embolism (day 8).

Table 3. A comparison of surgical endpoints and medical complications in the 2 cohorts

Discussion

The results of this study show that adopting an ER program helped achieve substantial reduction in 4 important outcomes. Firstly, the LOS almost halved without an increase in the rates of re-admission or RTT. Secondly, postoperative blood transfusion requirements were dramatically reduced. Thirdly, the protocol resulted in a fall in recorded 30-day cardiac ischemic events. Finally, and most importantly, both 30- and 90-day mortality declined.

LOS after ER arthroplasty remains a multifactorial issue (Husted et al. Citation2010a). In our experience, the coupling of procedural innovation and patient education has resulted in a consistent decline in LOS. This has been maintained well beyond the introduction period associated with high staff enthusiasm. The reduced transfusion rate most likely results from the use of Tranexamic acid, confirming its efficacy in reducing perioperative blood loss and allogenic blood transfusion in hip and knee arthroplasty (Alshryda et al. Citation2011, Sukeik et al. Citation2011). This was not accompanied by any increase in embolic complications; in fact, the incidence of stroke, DVT, and PE was recorded less often in ER. Despite the higher prevalence of comorbidities (hypertension, ischemic heart disease, COPD, and type-2 diabetes), ER patients suffered fewer cardiac ischemic events.

The cost of consumables per procedure is modest (e.g. Tranexamic acid €3.67 per gram, Levobupivacaine €28.4, catheter €9.5, ambIT pump €35.5, Cryo/Cuff €47). 7-day rather than 5-day availability of physiotherapy costs €35.5 per procedure. This means an additional unit cost of €112 for THAs and €160 for TKAs. The ER group had 11,400 bed days less than the traditional group. A conservative estimate for the cost of an elective orthopaedic bed was €320 a day in 2008 (Jones Citation2008). Thus, there was effectively €3.5 million of savings with this cohort of ER patients. These released bed days increased the effectivity of the unit, as evidenced by the shorter period of time to complete 3,000 procedures with the ER program than with the traditional protocol (37 months as opposed to 49 months). Reduced transfusion also has cost implications, at €145– €166 per unit (NHS Blood and Transplant 2012). The reduced medical complications with the associated physical, social, and financial implications further justify an ER protocol.

This study had some limitations. The 2 cohorts were not concurrent. The ER patients and staff looking after them benefitted from educational measures to help reduce LOS. These were both unselected cohorts, and the higher proportions of females and of TKAs during the ER period were incidental. There were changes in DVT prophylaxis regimen during both periods, but these reflected changes in NICE guidance (NICE 2007, 2011). The changes in antibiotic prophylaxis mentioned above may also have had a confounding influence on medical complications. Also, the ER cohort was more recent, and would have intuitively benefitted from advances in diagnostic and therapeutic modalities. Nevertheless, this is the largest series of consecutive and unselected primary hip and knee arthroplasties reported to date, and confirms that Enhanced Recovery is practical, safe for patients, and cost-effective.

SK and MR designed the study. SK and AM collected the data. KE, IC, MR, and PP implemented the protocol. SK, AM, SM, and MR prepared the manuscript. All the authors reviewed the manuscript.

We gratefully acknowledge the help of all the contributing surgeons, anesthetists, theater practitioners, nursing staff, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, business managers, and information managers working at Northumbria Healthcare NHS Trust.

No competing interests declared.

- Abuzakuk TM, Coward P, Shenava Y, Kumar VS, Skinner JA. The management of wounds following primary lower limb arthroplasty: a prospective, randomized study comparing hydrofibre and central pad dressings. Int Wound J 2006; 3 (2): 133-7.

- Alshryda S, Sarda P, Sukeik M, Nargol A, Blenkinsopp J, Mason JM. Tranexamic acid in total knee replacement: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2011; 93 (12): 1577-85.

- Aveline C, Leroux A, Vautier P, Cognet F, Le Hetet H, Bonnet F. Risk factors for renal dysfunction after total hip arthroplasty. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim 2009; 28 (9): 728-34.

- Brämer GR. International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems. Tenth revision. World Health Stat Q 1988; 41 (1): 32-6.

- Clarke JV, Deakin AH, Dillon JM, Emmerson S, Kinninmonth AW. A prospective clinical audit of a new dressing design for lower limb arthroplasty wounds. J Wound Care 2009; 18 (1): 5-8, 10-1.

- Department of Health. Health Service Circular HSC 2007/001. Better blood transfusion– Safe and appropriate use of blood. London; 2007.

- Holm B, Kristensen MT, Bencke J, Husted H, Kehlet H, Bandholm T. Loss of knee-extension strength is related to knee swelling after total knee arthroplasty. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2010; 91: 1770-6.

- Husted H, Holm G, Jacobsen S. Predictors of length of stay and patient satisfaction after hip and knee replacement surgery: fast-track experience in 712 patients. Acta Orthop 2008; 79 (2): 168-73.

- Husted H, Hansen HC, Holm G, Bach-Dal C, Rud K, Andersen KL, Kehlet H. What determines length of stay after total hip and knee arthroplasty?A nationwide study in Denmark. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2010a; 130 (2): 263-8.

- Husted H, Otte KS, Kristensen BB, Orsnes T, Kehlet H. Readmissions after fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2010b; 130 (9): 1185-91.

- Husted H, Otte KS, Kristensen BB, Ørsnes T, Wong C, Kehlet H. Low risk of thromboembolic complications after fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty. Acta Orthop 2010c; 81 (5): 599-605.

- Jensen CD, Steval A, Partington PF, Reed MR, Muller SD. Return to theatre following total hip and knee replacement, before and after the introduction of rivaroxaban: a retrospective cohort study. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2011; 93 (1): 91-5.

- Jones R. Costing orthopaedic interventions. Br J Healthcare Management 2008; 14 (12): 539-47.

- Jones S, Alnaib M, Kokkinakis M, Wilkinson M, St Clair Gibson A, Kader D. Pre-operative patient education reduces length of stay after knee joint arthroplasty. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2011; 93 (1): 71-5.

- Larsen K, Hansen TB, Søballe K, Kehlet H. Patient-reported outcome after fast-track hip arthroplasty: a prospective cohort study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2010; 8: 144.

- Malviya A, Martin K, Harper I, Muller SD, Emmerson KP, Partington PF, Reed MR. Enhanced recovery program for hip and knee replacement reduces death rate. Acta Orthop 2011; 82 (5): 577-81.

- National Electronic Library for Medicines. London and South East Regional Medicines Information Service. 25 January 2010. http://www.nelm.nhs.uk/en/NeLM-Area/Other-Lib-Updates/Drug-Discontinuation-And-Shortage/Shortage-of-tranexamic-acid-injection-Cyclokapron-injection/. Accessed 20 February 2013.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Venous thromboembolism: reducing the risk of venous thromboembolism (deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism) in inpatients undergoing surgery. (Clinical guideline CG46) 2007. http://www.nice.org.uk/CG046. Accessed 15 May 2013.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Venous thromboembolism: reducing the risk. (Clinical guideline CG92) 2011. http://www.nice.org.uk/CG092. Accessed 15 May 2013.

- Nechleba J, Rogers V, Cortina G, Cooney T. Continuous intra-articular infusion of bupivacaine for postoperative pain following total knee arthroplasty. J Knee Surg 2005; 18 (3): 197-202.

- NHS Blood and Transplant. Strategic Plan 2012 – 2017. http://www.nhsbt.nhs.uk/strategicplan/blood_components/ (date last accessed 10 Aug 2012).

- NHS Connecting for Health. OPCS Classification of Interventions and Procedures. Version 4.5. London: TSO, 2009.

- Schroer WC, Diesfeld PJ, LeMarr AR, Reedy ME. Benefits of prolonged postoperative cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor administration on total knee arthroplasty recovery: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Arthroplasty (6 Suppl) 2011; 26: 2-7.

- Sprowson A, Symes T, Khan SK, Oswald T, Reed MR. Changing antibiotic prophylaxis for primary joint arthroplasty affects postoperative complication rates and bacterial spectrum. Surgeon 2012 Epub ahead of print.

- Sukeik M, Alshryda S, Haddad FS, Mason JM. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the use of tranexamic acid in total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2011; 93 (1): 39-46.