Abstract

Background and purpose Previous studies of patients who have undergone total hip arthroplasty (THA) due to femoral head necrosis (FHN) have shown an increased risk of revision compared to cases with primary osteoarthritis (POA), but recent studies have suggested that this procedure is not associated with poor outcome. We compared the risk of revision after operation with THA due to FHN or POA in

the Nordic Arthroplasty Register Association (NARA) database including Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden.

Patients and methods 427,806 THAs performed between 1995 and 2011 were included. The relative risk of revision for any reason, for aseptic loosening, dislocation, deep infection, and periprosthetic fracture was studied before and after adjustment for covariates using Cox regression models.

Results 416,217 hips with POA (mean age 69 (SD 10), 59% females) and 11,589 with FHN (mean age 65 (SD 16), 58% females) were registered. The mean follow-up was 6.3 (SD 4.3) years. After 2 years of observation, 1.7% in the POA group and 3.0% in the FHN group had been revised. The corresponding proportions after 16 years of observation were 4.2% and 6.1%, respectively. The 16-year survival in the 2 groups was 86% (95% CI: 86–86) and 77% (CI: 74–80). After adjusting for covariates, the relative risk (RR) of revision for any reason was higher in patients with FHN for both periods studied (up to 2 years: RR = 1.44, 95% CI: 1.34–1.54; p < 0.001; and 2–16 years: RR = 1.25, 1.14–1.38; p < 0.001).

Interpretation Patients with FHN had an overall increased risk of revision. This increased risk persisted over the entire period of observation and covered more or less all of the 4 most common reasons for revision.

Several studies of patients with femoral head necrosis (FHN) who have undergone total hip arthroplasty (THA) have shown an increased risk of revision compared to cases with primary osteoarthritis, but the literature in this field is not unanimous (Chandler et al. Citation1981, Cornell et al. Citation1985, Mont and Hungerford Citation1995). We therefore estimated the risk of revision for patients with THA due to non-traumatic FHN and for patients with primary osteoarthritis (POA). To obtain a sufficiently large material, we used the Nordic Arthroplasty Register, which covers data from the Danish, Finnish, Norwegian, and Swedish national registries.

Patients and methods

Sources of data

The Nordic Arthroplasty Register Association (NARA) was started in 2007 as a common database for Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. Finland joined the project in 2010. From 1995, all 4 countries have used individual-based registration of operations and patients. The NARA database consists of data on hip replacements compiled from the 4 national joint replacement registries (Havelin et al. 2009). At the time of the analysis, the database included 536,418 operations performed between January 1, 1995 and December 31, 2011. 436,915 hips had been operated due to POA or FHN. All surface replacements and operations with missing information on any of the variables analyzed were excluded, leaving 427,806 cases with THA for the study.

There were 11,589 hips with FHN and 416,217 hips with POA. Follow-up started on the day of operation and ended on the day of revision, death, or December 31, 2011. Revision was defined as removal or exchange of at least one of the prosthetic components. The average follow-up was 6.3 years (SD 4.3) (range 0–17) in the POA group and 5.8 years (SD 4.2) (range 0–17) in the FHN group.

Statistics

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was used to estimate the unadjusted cumulative revision rates. Data are presented as cumulative survival (CS) with 95% confidence interval (CI). Cox multiple regression analysis was used to study the relative risk (RR) of revision, adjusting for age (5 groups: < 50, 50–59, 60–69, 70–79, ≥ 80 years; or 2 groups: < 70 and ≥ 70), sex, and type of fixation. The proportional hazards assumption was evaluated with studies of survival curves and computation and plotting of Schoenfeld residuals. Analysis of fixation was separated into cemented or uncemented fixation of the cup and stem (1 variable each). The maximum follow-up was set at 16 years. At this time, 3,402 patients in the FHN group (29%) and 82,143 in the POA group (20%) had died.

The risks of revision due to aseptic loosening, dislocation, deep infection, and periprosthetic fracture were studied separately. Exploratory analyses revealed non-proportionality over time and high residuals in some of the analyses. Thus, the risk of revision for any reason was split into 2 periods, 0–2 years and 2–16 years after the operation. Further subgrouping or group modification was done in the analyses of revision due to loosening, infection, and periprosthetic fracture due to time dependency of 1 or 2 of the variables age, sex, and stem fixation. To validate our calculations, they were repeated using 11,589 matched THAs in the group with POA for comparison. These operations were matched based on age, sex, and fixation of the cup and stem. The matching was performed by computation of propensity scores (nearest-neighbor matching) (Rosenbaum and Rubin 1983). This validation gave essentially the same results (data not shown). All tests were 2-tailed and any p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software version 20.0 and the R statistics package.

Ethics

The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (J. no. 2008-41-2024), the Finnish National Committee for Medical Research Ethics (TUKIJA), and the Norwegian and the Swedish Data Inspection Boards.

Results

Demographics

During the period of observation, the relative ratio of FHN to POA patients remained fairly constant, slightly below or above 3%. 58% of the THAs in patients with FHN were in females and 59% of the THAs in patients with POA were in females.

Patients with FHN had a lower mean age (65 years (SD 16)) than those operated due to POA (69 years (SD 10)) (p < 0.001). Overall, patients with FHN were more evenly distributed between the 5 age groups studied (< 50, 50–59, 60–69, 70–79, ≥ 80 years) ().

Table 1. Patient demographics, type of fixation, and causes of revision

Type of fixation

Patients with POA received cemented prostheses more frequently (63%) than those with FHN (59%) (all-cemented; ). The distribution regarding uncemented prostheses was reversed (23% and 26%). In the remaining groups of fixation, hips with FHN were more frequently represented (8.3% POA and 9.1% FHN, respectively, for hybrids and 5.0% POA and 5.9% FHN for reversed hybrids). Thus, uncemented cups and stems were used more frequently in hips with FHN (cups: 32% and 35%; stems: 29% and 32%).

Survival

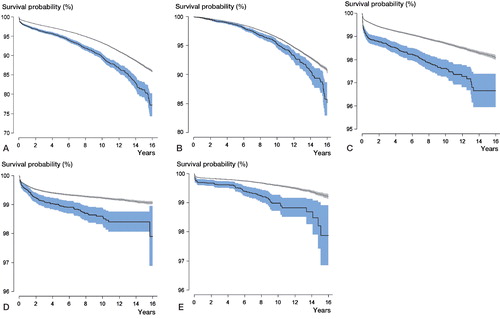

At 16 years, 6.9% of the hips had been revised in the group with FHN and 4.7% had been revised in the POA group. For all reasons for revision studied, the revision rate was higher in the study group (). After 2 years, the survival using all reasons for revision as outcome was lower in the FHN group than in the POA group (97% (95% CI: 96–97) and 98% (CI: 98–98); p < 0.001). After 16 years, the survival had decreased to 77% (CI: 74–80) and 86% (CI: 86–86), respectively (p < 0.001). The 16-year survival was also lower in the FHN group when each of the outcomes loosening, infection, dislocation, and periprosthetic fracture were studied separately (p < 0.001) (Figure).

Mean survival ± 95% CI according to Kaplan-Meier based on revision for any reason (panel A), loosening (B), dislocation (C), infection (D), and periprosthetic fracture (E). Light gray: primary osteoarthritis; dark gray: femoral head necrosis.

Separation of FHN patients who were operated 1995–2002 and 2003–2011 revealed slightly lower 2-year survival for those operated during the later period (98% (CI: 97–98) vs. 96% (CI: 96–97); p = 0.002). After 8 years, the survival became more equal (92% (CI: 91–93) and 92% (CI: 90–93); p = 0.06).

Risk of revision for any reason

A Cox regression model showed that the FHN group had more than twice the risk of having revision within 6 months compared to the POA group (adjusted RR = 2.2, CI: 1.9–2.6, detailed data not shown). At 2 years, the adjusted relative risk had decreased to 1.4 (CI: 1.3–1.5) (). From 2 to 16 years, the unadjusted and adjusted risks decreased further, but were still higher in the FHN than in the POA group (adjusted RR = 1.3, CI: 1.1–1.4) (). Age-stratified analyses during the entire follow-up period (0–16 years) showed that the unadjusted and adjusted risk of revision was statistically significantly elevated for FHN patients compared to POA patients over 50 years of age, whereas in the youngest group (< 50 years) the risk was similar (p ≥ 0.09) ().

Table 2. Relative risk of revision for any reason, from 0 to 2 years and after 2 years

Table 3. Unadjusted and adjusted relative risk of revision in FHN and POA for any reason up to 2 years, separated into age groups. Adjustment for sex and for cup and stem fixation (risk ratios for covariates are not shown)

Risk of revision for specific reasons

Before any adjustment, patients with FHN showed an increased risk of being revised due to loosening. Further analyses were done on data stratified for age and stem fixation, in order not to violate the proportional hazards assumption. Thus, in these analyses hips operated with cemented and cementless stems were studied separately. After adjusting for sex, age within each stratum, and cup fixation, we found increased risk of revision in the FHN group in patients who were 70 years and older in the group that was operated with a cemented stem (Table 4, see Supplementary data). Patients 70 years and older with FHN and operated with an uncemented stem also showed a higher risk, but this was not statistically significantly different from that for those with primary OA. The number of hips in patients with FHN who were operated with an uncemented stem was, however, low (383 cases).

During the entire period of observation, the risk of revision due to dislocation was twice as high in the FHN group (Table 5, see Supplementary data). Revision because of infection was stratified for age (< 70 and ≥ 70 years) due to non-proportionality. After adjustment for covariates, the risk of being revised because of infection was increased in patients with FHN by about 70–80% depending on age (Table 6, see Supplementary data).

Without any adjustment, patients with FHN had more than twice the risk of being revised due to periprosthetic fracture compared to those operated due to POA. The risk ratio between males and females and between cemented and uncemented stems varied over time. The analyses were therefore stratified for sex and choice of stem fixation. Both males and females with FHN who were operated with a cemented stem showed an increased risk of being revised due to periprosthetic fracture. This increase in risk was particularly high in females. In patients operated with an uncemented stem, the situation was reversed. Males with FHN had more than twice the risk of that in males with POA, whereas in females the risk ratio was lower (Table 7, see Supplementary data).

Discussion

Primary OA is the most common diagnosis for THA in studies from Europe, USA, and Australia, while FHN has been the most common diagnosis in several studies reported from Asia (Bouchain and Delorme Citation2003, Canadian Joint Replacement Registry 2010, Lee et al. Citation2010, Australian Orthopedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry 2012). To our knowledge, there have been no reports focusing on the differences in the incidence of FHN worldwide. In a review article based on data collected until 1991, Mont and Hungerford (Citation1995) estimated that between 5% and 12% of the THAs in the USA were performed due to avascular necrosis. In a recent publication, Tofferi (2012) reported an incidence of about 10%, suggesting that this share has remained rather constant. In our study, the relative frequency was 2.2% of the total amount of THRs performed 1995–2011. Even though this figure is considerably lower, it did not change over the period of observation.

Early clinical studies of THA inserted in cases with FHN reported high failure rates (Chandler et al. Citation1981, Cornell et al. Citation1985, Mont and Hungerford Citation1995). More recent studies have, however, found that the revision rate in patients with FHN is comparable to those reported in cases with POA (Piston et al. Citation1994, Wei et al. Citation1999 Fyda et al. Citation2002, Hungerford et al. Citation2006, Conroy et al. Citation2008, Bose and Baruah Citation2010, Kim et al. Citation2010, Johannson et al. Citation2011). Wei et al. (Citation1999) concluded that patients with FHN could expect results similar to those observed in patients with primary OA, even after revision surgery. Idiopathic FHN is a rare diagnosis and many of the studies performed have been small and retrospective (Table 8, see Supplementary data). In the present study, the risk of early revision was slightly higher in the patient group with FHN during the late period (2003–2011), but this difference appeared to level out with time. This observation contradicts the results of Johannson et al. (Citation2011). These authors did, however, separate their patients into those operated before 1990 and those operated during 1990 and later, which could be one explanation.

Previous registry studies have shown inconsistent results regarding the risk of revision after operation with THA in these patients. In the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register, Furnes et al. (2001) did not find an increased risk of revision based on 415 cases compared to 37,215 THAs operated because of POA. Conroy et al. (Citation2008) evaluated data from the Australian Register and found an increased risk of revision due to dislocation in these cases. In a literature review including 3,277 THAs in 2,593 patients, Johannson et al. (Citation2011) found that the revision rate was lower in patients operated after 1990. It was higher in patients with FHN associated with sickle cell disease, Gaucher disease, or renal failure, but these high-risk groups only constituted less than 20% of the cases. Johnsen et al. (Citation2006) studied 1,093 THA patients in the Danish Hip Arthroplasty Register who were operated between 1995 and 2001 because of FHN. They observed an increased risk of revision during the postoperative month, but no difference compared to POA 6 months to 9 years after the index operation. In general, the reason for revision varies over time (Garellick et al 2009). During the first 2 years, dislocation and infection are the most common causes whereas revisions due to loosening or lysis will peak later on. Thus, these discrepancies between studies could be related to variable time to follow-up—and also to skewed implant selection and insufficient numbers included.

A limitation of most registry-based studies is that only a revision operation is considered as a definition of failure. Some patients with poor clinical results may not be revised, and some with radiographic failure have minor or no clinical symptoms or may not be revised due to poor general health. In this respect, however, younger patients are probably revised earlier than elderly patients. This might have skewed the results in the present study since patients with FHN were somewhat younger than those with primary OA. The Nordic registries have complete coverage, which means that all hospitals participate. The completeness of data on primary procedures varies between 86% and 99% in the 4 countries. Revisions are probably under-reported to a certain extent, but there is no reason to believe that any such under-reporting should differ between the 2 patient groups studied. However, it is possible that centers with more experience performed the majority of the replacements in the young patients and thereby more of the patients with FHN, which could have been a possible source of bias.

We found that the risk of revision in FHN patients for any reason was more than double during the first 6 postoperative months. After 2 years, it decreased to about 50%. Compared to the group with POA, revisions due to dislocation, infection, and periprosthetic fracture were especially common. These causes—and particularly dislocation and infection—often result in early revisions. Revision due to periprosthetic fractures may also occur early, and especially with use of uncemented stems. High age was a risk factor for early revision, whereas revisions after 2 years were more common in younger patients. The reason may be that older patients more often suffer from dislocation and infection whereas loosening is a more important problem in the younger population.

Previous studies have found that men have a higher risk of being revised for any reason than women (Fukushima et al. 2010, Katz et al. Citation2012). This is in accordance with our findings. Further studies of the 4 most common reasons for revision revealed that there was poorer outcome for males concerning loosening, infection, and periprosthetic fracture, whereas the risk of revision due to dislocation was about the same.

FHN has been associated with risk factors and/or diseases that, in different ways, may influence the outcome of a THR. Some of the most common risk factors or diseases are excessive alcohol consumption, smoking, heart/kidney transplantation, corticosteroids, and systemic lupus erythematosus (Bradbury et al. Citation1994, Mont and Hungerford Citation1995, Lieberman et al. Citation2000, Mahoney et al. Citation2005, Mont et al. Citation2006). These conditions or their treatment will frequently result in inferior bone quality and reduced resistance to infections. Mental confusion in association with various types of abuse might also influence the risk of dislocation, infection, and periprosthetic fracture. Another contributory factor for increased risk of revision in patients with FHN may be that osteonecrosis tends to affect younger individuals. FHN predominated in the age group below 50 years, with a group mean of about 65 years. According to the age-stratified analyses, there was an increase in risk for all age groups except the one below 50 years of age. This rather speaks against the idea that age should have a decisive influence on the increased revision rate in cases with this diagnosis. Patients with primary OA were generally older, which is in line with previously reported data (Johannson et al. Citation2011).

Younger people have higher activity than older patients, placing more stress on the implant. On the other hand, the increase in risk of revision because of loosening in patients with FHN was not as pronounced as for the other 3 causes studied. After adjustment for covariates, a statistically significant increase could only be established for patients over 70 years of age who were operated with a cemented stem. Also, in the group operated with an uncemented stem the risk ratio was higher—but not statistically significantly so. However, uncemented stems were rarely used in these cases, resulting in few observations. These findings suggest that any influence of FHN (or its causes) on the quality of the bone—with the potential to influence the risk of loosening—is only relevant in older patients.

Compared to patients with POA, we found that an increased risk of revision was associated with the presence of FHN in patients who were 50 years of age or more. The risk ratio increased up to 60–69 years, and tended to decrease thereafter. The reason for this age dependence is not clear. It could be related to our observation that the influence of FHN on the risk of revision varies between causes of revision. Dislocation, infection, and periprosthetic fracture had the highest risk ratios. These complications are common in the early period after a THA and are more common in elderly patients. With time, loosening will become more and more a cause of revision; we only (and after adjustment for covariates) found a difference between the diagnoses in patients 70 years and older who were operated with a cemented stem.

FHN increases the risk of a future revision in a complex way. It could be that bone necrosis results in secondary changes in the quality of the bone and soft tissues around the hip, which contributes to these complications. It does seem more probable that metabolic changes or other factors preceding the development of necrosis are responsible. To explore these issues, further cross-matching with healthcare and pharmaceutical registers would be of interest.

In summary, patients with FHN have a higher risk of being revised than those operated due to POA—and especially up to 2 years after the primary operation. Over the entire observation period of 16 years, the most pronounced differences were observed for the causes periprosthetic fracture, dislocation, and infection.

Supplementary data

Tables 4-8 are available at Acta’s website (www.actaorthop.org), identification number 6577.

Supplementary Material

Download PDF (45.8 KB)Data collection: GG, JK, AMF, OF, LIH, KM, SO, AP, and PP. Original idea: JK after discussion in the NARA group. Manuscript preparation: CB and JK. Revision of manuscript: all authors. Data preparation and statistics: CB, MM, and JK.

No competing interests declared.

- Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry. Annual Report 2012. www.aoanjrr.dmac.adelaide.edu.au 2008 AOANJRRAAR. http://www.dmac.adelaide.edu.au(aoanjrr Accessed Feb 10 2010.

- Australian Orthopedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry. Annual Report Adelaide AOA 2012.

- Bose VC, Baruah BD. Resurfacing arthroplasty of the hip for avascular necrosis of the femoral head: a minimum follow-up of four years. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2010; 92 (7): 922-8.

- Bouchain G, Delorme D. Novel hydroxamate and anilide derivatives as potent histone deacetylase inhibitors: synthesis and antiproliferative evaluation. Curr Med Chem 2003; 10 (22): 2359-72.

- Bradbury G, Benjamin J, Thompson J, Klees E, Copeland J. Avascular necrosis of bone after cardiac transplantation. Prevalence and relationship to administration and dosage of steroids. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1994; 76 (9): 1385-8.

- Canadian Joint Replacement Registry. Hip and knee replacements in Canada. 2008-2009 Annual Report. http://www.cihi.ca/cjrr Accessed Feb 10 2010. 2010.

- Chandler HP, Reineck FT, Wixson RL, McCarthy JC. Total hip replacement in patients younger than thirty years old. A five-year follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1981; 63 (9): 1426-34.

- Conroy JL, Whitehouse SL, Graves SE, Pratt NL, Ryan P, Crawford RW. Risk factors for revision for early dislocation in total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2008; 23 (6): 867-72.

- Cornell CN, Salvati EA, Pellicci PM. Long-term follow-up of total hip replacement in patients with osteonecrosis. Orthop Clin North Am 1985; 16 (4): 757-69.

- Fukushima W, Fujioka M, Kubo T, Tamakoshi A, Nagai M, Hirota Y. Nationwide epidemiologic survey of idiopathic osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Clin Orthop 2010; (468) (10): 2715-24.

- Furnes O, Lie SA, Espehaug B, Vollset SE, Engesaeter LB, Havelin LI. Hip disease and the prognosis of total hip replacements. A review of 53,698 primary total hip replacements reported to the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register 1987. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2001; 83 (4): 579-86.

- Fyda TM, Callaghan JJ, Olejniczak J, Johnston RC. Minimum ten-year follow-up of cemented total hip replacement in patients with osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Iowa Orthop J 2002; 22: 8-19.

- Garellick G, Kärrholm J, Rogmark C, Herberts P. Göteborg: Dept of Orthopaedics, Sahlgrenska University Hospital; 2009 The Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register, Annual Report 2009.

- Hungerford MW, Hungerford DS, Khanuja HS, Pietryak BP, Jones LC. Survivorship of femoral revision hip arthroplasty in patients with osteonecrosis. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) (Suppl 3) 2006; 88: 126-30.

- Johannson HR, Zywiel MG, Marker DR, Jones LC, McGrath MS, Mont MA. Osteonecrosis is not a predictor of poor outcomes in primary total hip arthroplasty: a systematic literature review. Int Orthop 2011; 35 (4): 465-73.

- Johnsen SP, Sørensen HT, Lucht U, Søballe K, Overgaard S, Pedersen AB. Patient-related predictors of implant failure after primary total hip replacement in the initial, short- and long-terms. A nationwide Danish follow-up study including 36,984 patients. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2006; 88 (10): 1303-8.

- Katz JN, Wright EA, Wright J, Malchau H, Mahomed NN, Stedman M, et al. Twelve-year risk of revision after primary total hip replacement in the u.s. Medicare population. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2012; 94 (20): 1825-32.

- Kim YH, Choi Y, Kim JS. Cementless total hip arthroplasty with ceramic-on-ceramic bearing in patients younger than 45 years with femoral-head osteonecrosis. Int Orthop 2010; 34 (8): 1123-7.

- Lee MS, Hsieh PH, Shih CH, Wang CJ. Non-traumatic osteonecrosis of the femoral head–from clinical to bench. Chang Gung Med J 2010; 33 (4): 351-60.

- Lieberman JR, Scaduto AA, Wellmeyer E. Symptomatic osteonecrosis of the hip after orthotopic liver transplantation. J Arthroplasty 2000; 15 (6): 767-71.

- Mahoney CR, Glesby MJ, DiCarlo EF, Peterson MG, Bostrom MP. Total hip arthroplasty in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection: pathologic findings and surgical outcomes. Acta Orthop 2005; 76 (2): 198-203.

- Mont MA, Hungerford DS. Non-traumatic avascular necrosis of the femoral head. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1995; 77 (3): 459-74.

- Mont MA, Jones LC, Hungerford DS. Nontraumatic osteonecrosis of the femoral head: ten years later. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2006; 88 (5): 1117-32.

- Piston RW, Engh CA, De Carvalho PI, Suthers K. Osteonecrosis of the femoral head treated with total hip arthroplasty without cement. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1994; 76 (2): 202-14.

- Tofferi JK. Avascular Necrosis. Medscape Updated Jan 2012. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/333364-overview

- Wei SY, Klimkiewicz JJ, Lai M, Garino JP, Steinberg ME. Revision total hip arthroplasty in patients with avascular necrosis. Orthopedics 1999; 22 (8): 747-57.