A 52-year-old man presented at our tertiary referral center for orthopedic oncology with progressive pain in the left hip and leg. Conventional radiographs and CT showed a relatively well-defined 8 × 9 × 11 cm expansile osteolytic lesion. The lesion extended from the left os ischium to the inferior ramus of the left os pubis (). MRI confirmed the presence of a highly vascularized lesion with extension into the adductor loge, obturator externus, and pectineus muscles (). Preoperative CT-guided core needle biopsies confirmed the diagnosis of giant cell tumor of bone (GCTB) ().

Figure 1. A. A well-defined 11 × 9 × 8 cm expansile osteolytic lesion extending from the left ischium to the lower arm of the left pubis in a 52-year-old man with progressive pain in his left hip and leg. Radiographic findings were consistent with the diagnosis of GCTB. B. 3 months after the start of denosumab treatment, there was no progression of disease and increased radiopacity of the lesion. C. 5 years after resection of the ischium and inferior ramus of the pubis followed by phenolization and cementation of the posterior acetabular wall, there was no evidence of recurrent disease.

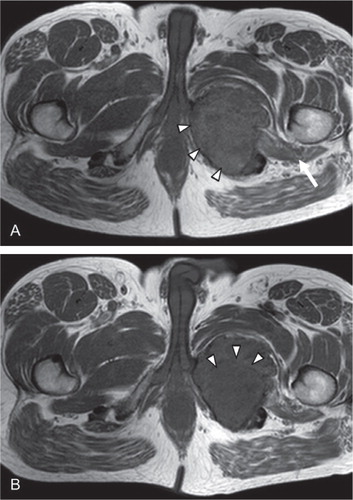

Figure 2. A. T1-weighted MR imaging before treatment with denosumab showed a highly vascularized lesion (arrowheads) extending into the surrounding soft tissues (arrow), consistent with GCTB. B. T1-weighted MR imaging 3 months after the start of denosumab treatment showed that there was no progression of disease. Areas of central necrosis were seen (arrowheads).

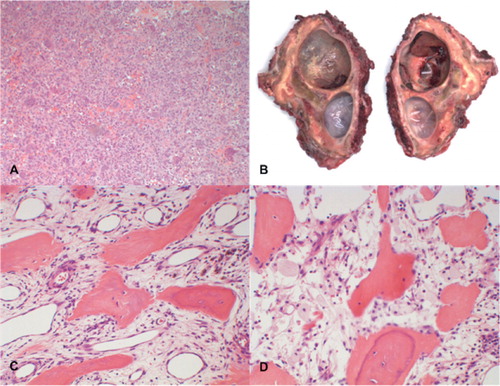

Figure 3. A. Histology of the biopsy specimen before the start of denosumab treatment showed numerous uniformly spaced giant cells with large vesicular nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and mononuclear cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm and nuclei similar to those of adjacent giant cells, which is consistent with the diagnosis of GCTB. B. Macro specimen of intralesional resection after 7 months of treatment with denosumab, showing 2 large cysts and focal clots. The resection planes were not free of reactive tissue. C and D. Histology of the surgical specimen showed stromal cells, scattered mononuclear spindle cells with elongated oval-shaped nuclei without evident atypia, and diffuse foamy macrophages. No multinucleated giant cells were seen.

In this patient with locally advanced GCTB at a surgically difficult anatomical location, we expected that neoadjuvant therapy with the receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-β ligand (RANKL) inhibitor denosumab would facilitate intralesional excision by creating a calcified rim around the tumor and its soft tissue component. The patient was treated over 7 months with denosumab, 120 mg subcutaneously every 4 weeks, with loading doses at study days 8 and 15 of a large worldwide phase-2 study for patients with locally advanced GCTB (www.clinicaltrials.gov, NCT00680992). During treatment, the patient did not experience any adverse reactions. He received standard daily oral calcium/vitamin D supplementation. Serum electrolytes were checked every 4 weeks, and no evident alterations were found. 2 months after the start of denosumab, the patient reported less pain. Radiographs showed remarkably increased radiopacity of the lesion (). MRI showed that there was no progression of disease, and areas of central liquefaction were noticed (). 7 months after the start of denosumab treatment, arterial embolization to prevent excessive intraoperative hemorrhage was followed by intralesional resection with phenolization and PMMA cementation of the osteotomy planes of os ischium, inferior ramus of os pubis, and acetabulum. The soft tissue extension observed previously showed an ossified rim, which facilitated surgical approach. No reconstruction was needed and no complications were reported (). Denosumab was continued for 6 months postoperatively. Histology of the surgical specimen showed GCTB with reactive stromal cells and scattered spindle cells with elongated oval-shaped nuclei without evident atypia. Diffusely clustered foamy macrophages were also seen. No multinucleated giant cells were seen, in contrast to previous biopsies, indicating a good response to denosumab (, 3D). Follow-up included physical examination and imaging on a regular basis. 5 years postoperatively, there were no signs of local recurrence or pulmonary metastases. Apart from occasional muscular cramps in the gluteal area, the patient does not suffer from any complaints and physical functioning is not impaired.

Discussion

Standard treatment for conventional GCTB of the long bones is curettage with local adjuvants such as phenol and polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA), resulting in recurrence rates between 12% and 34% (CitationBecker et al. 2008, CitationKivioja et al. 2008, CitationBalke et al. 2009, CitationKlenke et al. 2011). However, due to relatively high recurrence rates, more extensive surgery is indicated for high-risk GCTB with extraosseous extension, especially in the pelvic region (Van der CitationHeijden et al. 2012). More extensive primary surgery may be indicated in axial GCTB (CitationBalke et al. 2009), which may result in loss of function and higher risk of complications (CitationLeggon et al. 2004, CitationBalke et al. 2012).

Microscopically, GCTB is composed of rounded mononuclear macrophage-like osteoclast precursor cells, spindle-shaped mononuclear neoplastic stromal cells, and reactive multinucleated osteoclast-like giant cells capable of bone resorption (CitationAthanasou et al. 2013). RANKL is highly expressed by the mononuclear neoplastic stromal cells (CitationRoux et al. 2002, CitationMorgan et al. 2005, CitationBranstetter et al. 2012) and is believed to play an important role in osteoclast formation, differentiation, and survival.

Denosumab is a fully human monoclonal antibody with high affinity for RANKL (CitationKostenuik et al. 2009) and therapeutic potential in treatment of GCTB. The efficacy of denosumab for GCTB has been proven in prospective randomized trials, and it has recently been registered for advanced GCTB by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA). In an open-label phase-2 study, patients with recurrent or unresectable GCTB were treated with denosumab before surgery (CitationThomas et al. 2010). In 86% of patients (30 of 35), there was an objective response to denosumab therapy, defined as either > 90% elimination of giant cells on histological evaluation or no radiographic progression of the target lesion up to week 25. The interim analysis of a larger study (n = 282) was recently published, and confirmed the high efficacy of denosumab in GCTB (CitationChawla et al. 2013). 96% of surgically unsalvageable patients had no disease progression after a median follow-up of 13 months. 74 of 100 patients had no surgery and 16 of 26 underwent less morbid surgery after a median follow-up period of 9 months. Toxicity from denosumab is rare.

The role of radiotherapy as adjuvant treatment of GCTB needs to be redefined, now that denosumab has been registered for locally advanced GCTB. Given the promising short-term results of phase-II studies with denosumab, use of radiotherapy should be limited to rare cases of unresectable, residual, or recurrent GCTB (e.g. in axial locations) in which treatment with denosumab is not available, is contraindicated, or has been ineffective—and when surgery would lead to unacceptable morbidity.

By treating our patient with denosumab, we created a situation whereby safe intralesional resection could be performed instead of more extensive surgery. We did not find any complications or evidence of residual or local recurrent disease 5 years postoperatively. Future encouraging results with neoadjuvant denosumab could allow us to treat GCTB with intralesional surgery in cases where more extensive surgery would otherwise have been indicated. This would result in better surgical, oncological, and functional outcomes and would reduce recurrence and the risk of complications. The current phase-2 study (NCT00680992) will be able to determine the effectiveness and safety of neoadjuvant treatment with denosumab for GCTB. What the optimal treatment dose, interval, and duration of therapy should be and whether adjuvant denosumab would be useful after standard surgical treatment will be the subject of a future study being planned by EORTC.

LH wrote the manuscript. MAJS revised and corrected the manuscript. PDSD operated on the patient and revised the manuscript. HG is local PI for the NCT00680992 study, treated the patient with denosumab, and revised the manuscript. PCWH performed histopathological evaluation of preoperative biopsy and resection specimens, provided images, and revised the manuscript.

No competing interests declared.

- Athanasou NA, Bansal M, Forsyth R et al. Giant cell tumour of bone. In Fletcher CDM, Bridge JA Hogendoorn PCW Mertens F (Eds): “WHO Classification of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone.” Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), 2013: 321–4.

- Balke M, Streitbuerger A, Budny T et al. Treatment and outcome of giant cell tumors of the pelvis. Acta Orthop 2009; 80(5): 590–6.

- Balke M, Henrichs MP, Gosgheger G et al. Giant cell tumors of the axial skeleton. Sarcoma 2012; 2012: 410973.

- Becker WT, Dohle J, Bernd L et al. Local recurrence of giant cell tumor of bone after intralesional treatment with and without adjuvant therapy. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2008; 90(5): 1060–7.

- Branstetter DG, Nelson SD, Manivel J C et al. Denosumab induces tumor reduction and bone formation in patients with giant-cell tumor of bone. Clin Cancer Res 2012; 18: 4415–24.

- Chawla S, Henshaw R, Seeger L et al. Safety and efficacy of denosumab for adults and skeletally mature adolescents with giant cell tumour of bone: interim analysis of an open-label, parallel-group, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 2013; 14: 901–8.

- van der Heijden L, van de Sande M AJ, Dijkstra P DS. Soft tissue extension increases the risk of local recurrence after curettage with adjuvants for giant cell tumor of the long bones – A retrospective study of 93 patients. Acta Orthop 2012; 83(4): 401–5.

- Kivioja AH, Blomqvist C, Hietaniemi K et al. Cement is recommended in intralesional surgery of giant cell tumors: a Scandinavian Sarcoma Group study of 294 patients followed for a median time of 5 years. Acta Orthop 2008; 79(1): 86–93.

- Klenke FM, Wenger DE, Inwards C Y et al. Giant cell tumor of bone: risk factors for recurrence. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2011; 469(2): 591–9.

- Kostenuik PJ, Nguyen HQ, McCabe J et al. Denosumab, a fully human monoclonal antibody to RANKL, inhibits bone resorption and increases BMD in knock-in mice that express chimeric (murine/human) RANKL. J Bone Miner Res 2009; 24(2): 182–95.

- Leggon RE, Zlotecki R, Reith J et al. Giant cell tumor of the pelvis and sacrum: 17 cases and analysis of the literature. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2004; (423): 196–207.

- Morgan T, Atkins GJ, Trivett M K et al. Molecular profiling of giant cell tumor of bone and the osteoclastic localization of ligand for receptor activator of nuclear factor kappaB. Am J Pathol 2005; 167: 117.

- Roux S, Amazit L, Meduri G et al. RANK (receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa B) and RANK ligand are expressed in giant cell tumors of bone. Am J Clin Pathol 2002; 117: 210–6.

- Thomas DM, Henshaw R, Skubitz K M et al. Denosumab in patients with giant-cell tumour of bone: an open-label, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 2010; 11(3): 275–80.