Abstract

Background and purpose — Metaphyseal fractures heal in a rapid fashion that is different from the bone shaft healing process. Animal studies have focused on diaphyseal fractures. We investigated the metaphyseal fracture-healing process in rabbits.

Animals and methods — 60 rabbits (divided into 12 groups) underwent proximal tibial osteotomy, anatomical reduction, and fixation with screws. After surgery, the proximal tibiae were harvested at different time points for histology.

Results — No obvious osteonecrosis or bone resorption were found 2 weeks after surgery. From day 5 to week 5, woven bone or new trabeculae formed. From week 2, remodeling into lamellar bone started and reached a peak at week 6. These 3 stages overlapped. Histomorphometry showed that the structure changed as a unimodal curve.

Interpretation — The healing process of metaphyseal fractures appears to differ from the commonly studied healing process in diaphyseal fractures. It is rapid, and can be divided into 4 histological stages: cellular activation and differentiation, formation of woven bone, transformation of woven bone into lamellar bone, and further remodeling.

Most fractures of the extremities occur in metaphyseal bones, mainly trabecular. Healing of shaft fracture is a complex multi-step process in which intramembranous and endochondral ossification combine to complete the process (CitationRabie et al. 1996, CitationShapiro 2008). By contrast, metaphyseal fractures appear to heal in a more rapid fashion—differently from diaphyseal fractures. Numerous animal model studies have concentrated on diaphyseal fractures, whereas there have been few experimental studies on metaphyseal fractures (CitationJarry and Uhthoff 1971, CitationUhthoff and Rahn 1981, CitationNunamaker 1998, CitationStuermer et al. 2009).

We hypothesized that metaphyseal fractures heal through a different, special process. We designed a new rabbit-based metaphyseal fracture model for this study.

Animals and methods

Animals

60 New Zealand white rabbits, 6 months old, each weighing about 3.5 kg, were obtained from the Laboratory Animal Center of Peking University (Beijing, China). The animals were divided into 12 groups with 5 per group. All were anesthetized by injection of sodium pentobarbital (30 mg/kg) into the auricular vein. After surgery, they were returned to individual cages for recovery with free movement.

Surgical procedures

A 2-cm longitudinal skin incision was made medial to the knee joint. The joint was exposed while inspecting the medial plateau. An osteotomy was performed with the blade on the medial tibial plateau at the attachment of the medial meniscus anterior horn, resulting in a cleavage fracture (AO/OTA classification 41B1, Schatzker classification type IV). The size of the fragment was 0.5 cm × 1 cm × 1.5 cm. The reduction was performed in situ, then fixed with a single screw (stainless steel, diameter 1.5 mm and length 18 mm) ().

Figure 1. Screw fixation for medial tibial plateau fracture after anatomical reduction (right knee joint). The yellow arrow indicates the osteotomy line. The knee joint is shown in anterior view.

On postoperative days 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, and 11 and at weeks 2, 3, 4, 6, and 8, animals were killed with an overdose of sodium pentobarbital. The bilateral tibiae were harvested and fixed with 10% formalin for histological examination.

Histological examination

The proximal tibiae were fixed with 70% ethanol, dehydrated in ascending concentrations of ethanol, defatted in dimethyl benzene, and embedded in methyl methacrylate without decalcification. Undecalcified 5-μm coronal plane sections were stained with Giemsa, von Kossa, and Masson-Goldner techniques.

Bone histomorphometry

Nomenclature, symbols, and units used in bone histomorphometry have been well described in previous studies (CitationParfitt et al. 1987, Dempster et al. 2013). Using a semi-automatic digitizing system for bone histomorphometry (Leica QWin; Leica, Germany) with a final magnification of 50×, we examined the following parameters: trabecular bone volume (bone volume (BV)/tissue volume (TV)), trabecular thickness (Tb.Th), trabecular number (Tb.N) and trabecular separation (Tb.Sp). The areas measured were defined by a rectangular region between subchondral bone and epiphyseal line.

Statistics

Values for the quantitative data obtained are expressed as mean (SD). Differences between experimental groups were evaluated through analysis of variance (ANOVA), and post-hoc test with the Student-Newman-Keuls (SNK) method.

Ethics

This study was performed in accordance with the recommendations of the Institutional Animal Care Guidelines and it was given ethical approval by the Administration Committee for Experimental Animals, Peking University People’s Hospital (entry number 2011-24).

Results

Histological examination

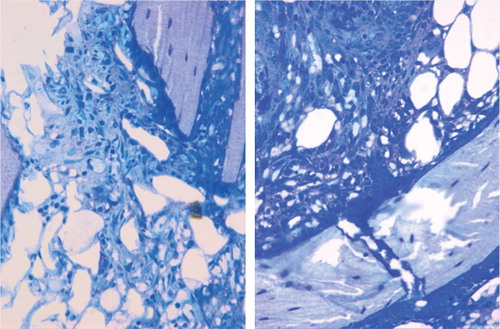

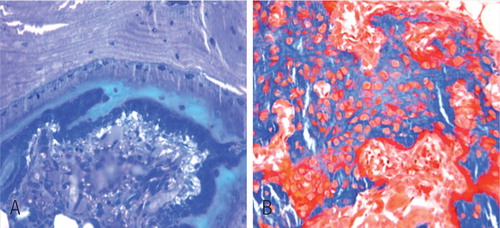

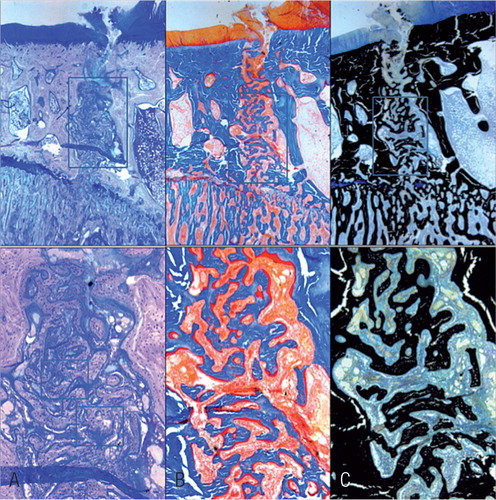

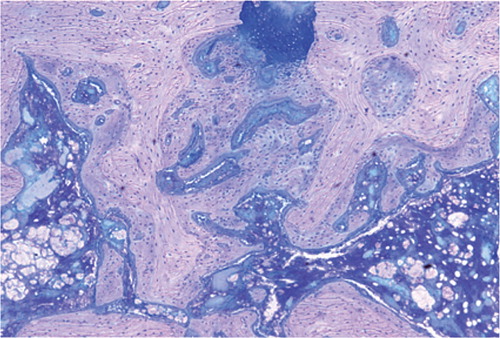

On postoperative day 1, the epiphyseal structure was disrupted without obvious hematoma. On day 3, a large number of presumed mesenchymal stem cells appeared within the fracture site. These cells proliferated and secreted collagen to form osteoid. The phenomenon was most active at the fracture gap, waning on both sides (). Already on day 5, primary woven bone formed with intensified cell proliferation. Much osteoid around the formed woven bone indicated that the formation of woven bone was still continuing (). On day 7, the amount of woven bone increased, with random matrix orientation. Bone formation could be divided into 2 patterns: one was lamellar bone formation based on the pre-existing trabeculae, and the other was woven bone formation—like islands in appearance—to connect the 2 sides of the fracture (). On day 9, cell proliferation and woven bone formation decreased. The woven structure began to transform into a more orderly lamellar structure with higher density and consistent distribution. The new trabeculae mineralized well and the grid structure formed. However, there was no typical lamellar structure yet. On day 11, the trabeculae were substantially larger than before. At week 2, the fracture site was filled with newly formed trabeculae. Typical lamella could be found on the surface of new-formed trabeculae. Osteoclasts in the lacuna on the surface of new trabeculae appeared (). At week 3, most new trabeculae were well mineralized and formed the typical lamellar structure (). At week 4, the basic multicellular unit (BMU) appeared. At week 8, there was normal bone structure.

Figure 2. The cellular proliferation occurred in the marrow inter-trabecular space and on the surface of pre-existing trabeculae. The shape of the cells was spindle-like or polygon-like, and they retained the appearance of mesenchymal cells (Giemsa stain, 200× magnification).

Figure 3. Histological features of the fracture site on postoperative day 5. The cellular proliferation kept increasing and formed the primary woven bone. Goldner staining (B) showed that there was a large amount of osteoid around the primary woven bone. Von Kossa staining (C) showed that deposition of calcium began on the osteoid and primary woven bone. (A Giemsa stain. Upper row 16×, middle row 50×, and lower row 200× magnification).

Figure 4. 2 different patterns of new bone formation. A. One occurred on the surface of pre-existing trabeculae to form the lamellar bone directly (Giemsa stain, 200× magnification). B. The other occurred at the inter-trabecular marrow, like a “map” with a high number of cells inside the new-formed woven bone (Goldner stain, 200× magnification).

Figure 5. Histological features of the fracture site at postoperative week 2. The new-formed trabeculae were larger than at the previous time point because of the lamellar bone formation. (Upper row 16x and low row 50× magnification. A Giemsa, B Goldner, and C von Kossa stain).

Figure 6. Histological features of the fracture site at postoperative week 3 (Giemsa stain, 50× magnification). The cell proliferation had finished. Most of the new-formed trabeculae had transformed into lamellar structures. The newly formed bone tissue could be distinguished from the original bone tissue due to the cell density, the cell size, and the orientation of the matrix.

Bone histomorphometry

BV/TV and Tb.N reached a peak at postoperative week 2 and then decreased. Tb.Sp was lowest at week 2, while the Tb.Th continued to increase (). The parameter data of histomorphometry changed as a unimodal curve.

Table 1. The structural parameters of trabecular bones measured by histomorphometry

Discussion

Cortical and cancellous bone have different structures. The cancellous bone affords a large surface area and vascularized marrow, which is helpful for deposition of new bone and offers a good blood supply (CitationFan et al. 2008). Numerous studies have investigated the fracture-healing process of diaphyseal fractures, whereas metaphyseal fractures have received much less attention (CitationJarry and Uhthoff 1971, CitationUhthoff and Rahn 1981, CitationNunamaker 1998, CitationStuermer et al. 2009, CitationAspenberg and Sandberg 2013). CitationJarry and Uhthoff (1971) compared stable and unstable metaphyseal fracture-healing models in rats, rabbits, and dogs. In stable fractures direct healing occurred based on the pre-existing trabeculae. Unstable fractures led to woven bone formation secondary to fibrous tissue. However, sparse callus formation was found in both conditions. CitationUhthoff and Rahn (1981) proposed that when fractures were not displaced, cancellous bone in metaphyseal areas could heal with limited callus formation.

CitationAspenberg and Sandberg (2013) studied histological biopsies from human distal radial fractures at different time points after injury, and found that the membranous ossification was the most predominant form of bone formation within marrow space. The woven bone could be directly formed in bone marrow with limited endochondral ossification. Cartilage was seldom seen. Cartilage was also seldom present in histological observations of specimens from knee-joint arthrodeses that were taken 4 weeks after surgery (CitationCharnley and Baker 1952). New woven bone formed on the surface of old trabeculae had united at the 2 sides.

The oscillating saw used by CitationJarry and Uhthoff (1971) may have caused extensive thermal bone damage. A novel animal model was developed to mimic metaphyseal fractures, using the distal femur in goats (CitationClaes et al.1997, 2009). However, the gap left between the fracture surface in Claes’ studies does not correspond to the clinical situation. In contrast to the study by Jarry and those by Claes, we used a blade to split the fracture in our study to avoid thermal injury. The fracture was fixed with screws after anatomical reduction in situ, to obtain better fixation than with Kirschner wires, which have often been used previously.

We found 2 patterns of bone formation different from the findings of CitationUhthoff and Rahn (1981). Cell proliferation initially began at the fracture site around vertical trabeculae. On the surface of these vertical trabeculae, osteoblast activity accelerated and formed the new woven bone that would connect the pre-existing trabeculae on both sides of the fracture; this was also described by CitationCharnley and Baker (1952). The activity of bone formation could lead to formation of lamellar bone directly on the surface of pre-existing trabeculae. These findings agree with the results of CitationJarry and Uhthoff (1971). Also, mesenchymal cells differentiated into osteoblasts and formed the woven bone directly in marrow tissue; this agrees with the findings of CitationAspenberg and Sandberg (2013). The woven bone formed island-like structures independently, which transformed into lamellar structures through remodeling. There was no callus formation during the whole process of fracture healing.

According to our findings, only intramembranous repair occurred in the fracture-healing process. We detected no hematoma, osteonecrosis, or inflammation in the cell proliferation stage. There was little loss of vascular function and little distortion of trabecular structure. The findings of CitationSandberg and Aspenberg (2014) concur with our results: stem cells played an important role in metaphyseal healing, and inflammation was not obvious at the early stages.

Our results revealed that BV/TV and Tb.N increased and reached a peak at 2 weeks after surgery. At the same time, Tb.Sp was minimal and Tb.Th increased continuously. Combined with the histology results, this indicated that the fracture had healed to the organization level at postoperative week 2. The increase in BV/TV in the early phase was mainly caused by the new-formed immature trabeculae (with higher numbers, smaller size, and lower separation).

At week 6, histomorphometry showed a slight decrease in BV/TV and then it returned to normal levels. This may be relevant to the high bone-remodeling activity in the same period. Compared to day −1, week 8 showed similar BV/TV, but higher Tb.Sp and Tb.Th and lower Tb.N, which might indicate that the bone remodeling would last for some time.

The study had certain limitations. Sodium pentobarbital was used as anesthetic agent. Although the animals anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital lay still in our study, they may have experienced stress reactions. Another weakness of the present study was the choice of 6-month-old rabbits. These rabbits were not skeletally mature, and animals that were more than 6 months may be more suitable for a fracture-healing model.

The metaphyseal fracture heals directly through intramembranous ossification involving 2 different locations, one in the marrow of the fracture site, the other on the surface of pre-existing trabeculae. The whole fracture-healing process consists of 4 histological stages: cellular activation and differentiation, formation of woven bone and new trabeculae, transformation of woven bone into lamellar bone, and further remodeling.

WC, DH, PZ, and BJ conceived and designed the experiments. WC, DH, NH, and YK performed them. WC, DH, PZ, and XY analyzed the data. WC, PZ, and BJ wrote the manuscript.

This study was funded by Chinese National Ministry of Science and Technology, 973 Project Planning (No. 2014CB542200), the National Natural Science Fund (Nos. 31271284, 31171150, 81171146, 30971526, 31100860, 31040043, 31371210, 81372044), the Educational Ministry New Century Excellent Talents Support Project (No. BMU 20110270), and the Ministry of Education Innovation Team (IRT1201).

No competing interests declared.

- Aspenberg P, Sandberg O. Distal radial fracture heal by direct woven bone formation. Acta Orthop 2013; 84: 297-300.

- Charnley J, Baker SL. Compression arthrodesis of the knee; a clinical and histological study. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1952; 34: 187-99.

- Claes L, Augat P, Suger G, Wilke HJ. Influence of size and stability of the osteotomy gap on the success of fracture healing. J Orthop Res 1997; 15: 577-84.

- Claes L, Veeser A, Gockelmann M, Simon U, Ignatius A. A novel model to study metaphyseal bone healing under defined biomechanical conditions. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2009; 129: 923-8.

- Dempster DW, Compston JE, Drezner MK, Glorieux FH, Kanis JA, Malluche H, Meunier PJ, Ott SM, Recker RR, Parfitt AM. Standardized nomenclature, symbols, and units for bone histomorphometry: a 2012 update of the report of the ASBMR Histomorphometry Nomenclature Committee. J Bone Miner Res 2013; 28: 2-17.

- Fan W, Crawford R, Xiao Y. Structural and cellular differences between metaphyseal and diaphyseal periosteum in different aged rats. Bone 2008; 42: 81-9.

- Jarry L, Uhthoff HK. Differences in healing of metaphyseal and diaphyseal fractures. Can J Surg 1971; 14: 127-35.

- Nunamaker DM. Experimental models of fracture repair. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1998; 355: S56-65.

- Parfitt AM, Drezner MK, Glorieux FH, Kanis JA, Malluche H, Meunier PJ, Ott SM, Recker RR. Bone histomorphometry: standardization of nomenclature, symbols, and units. Report of the ASBMR Histomorphometry Nomenclature Committee. J Bone Miner Res 1987; 2: 595-610.

- Rabie AB, Dan Z, Samman N. Ultrastructural identification of cells involved in the healing of intramembranous and endochondral bones. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1996; 25: 383-8.

- Sandberg O, Aspenberg P. Different effects of indomethacin on healing of shaft and metaphyseal fractures. Acta Orthop 2014 1-5. [Epub ahead of print].

- Shapiro F. Bone development and its relation to fracture repair. The role of mesenchymal osteoblasts and surface osteoblasts. Eur Cell Mater 2008; 15: 53-76.

- Stuermer EK, Sehmisch S, Tezval M, Tezval H, Rack T, Boekhoff J, Wuttke W, Herrmann TR, Seidlova-Wuttke D, Stuermer KM. Effect of testosterone, raloxifene and estrogen replacement on the microstructure and biomechanics of metaphyseal osteoporotic bones in orchiectomized male rats. World J Urol 2009; 27: 547-55.

- Uhthoff HK, Rahn BA. Healing patterns of metaphyseal fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1981; 160: 295-303.