Abstract

Background Hemiarthroplasties are performed in great numbers worldwide but are seldom registered on a national basis. Our aim was to identify risk factors for reoperation after fracture-related hemiarthroplasty in Norway and Sweden.

Material and methods A common dataset was created based on the Norwegian Hip Fracture Register and the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register. 33,205 hip fractures in individuals > 60 years of age treated with modular hemiarthroplasties were reported for the period 2005–2010. Cox regression analyses based on reoperations were performed (covariates: age group, sex, type of stem and implant head, surgical approach, and hospital volume).

Results 1,164 patients (3.5%) were reoperated during a mean follow-up of 2.7 (SD 1.7) years. In patients over 85 years, an increased risk of reoperation was found for uncemented stems (HR = 2.2, 95% CI: 1.7–2.8), bipolar heads (HR = 1.4, CI: 1.2–1.8), posterior approach (HR = 1.4, CI: 1.2–1.8) and male sex (HR = 1.3, CI: 1.0–1.6). For patients aged 75–85 years, uncemented stems (HR = 1.6, 95% CI: 1.2–2.0) and men (HR = 1.3, CI: 1.1–1.6) carried an increased risk. Increased risk of reoperation due to infection was found for patients aged < 75 years (HR = 1.5, CI: 1.1–2.0) and for uncemented stems. For open surgery due to dislocation, the strongest risk factor was a posterior approach (HR = 2.2, CI: 1.8–2.6). Uncemented stems in particular (HR = 3.6, CI: 2.4–5.3) and male sex increased the risk of periprosthetic fracture surgery.

Interpretation Cemented stems and a direct lateral transgluteal approach reduced the risk of reoperation after hip fractures treated with hemiarthroplasty in patients over 75 years. Men and younger patients had a higher risk of reoperation. For the age group 60–74 years, there were no such differences in risk in this material.

Being the main treatment option for displaced femoral neck fractures, hemiarthroplasties are performed in great numbers worldwide. In spite of this, these procedures are seldom registered nationally and there is little evidence regarding the best choice of implant design and surgical technique.

Randomized clinical trials (RCTs) may be underpowered to detect any differences in rare complications such as perioperative death, infection, and periprosthetic fractures. This is illustrated by the question of whether or not to choose cemented fixation, where the 3 RCTs on modern implants (Figved et al. Citation2009, Deangelis et al. Citation2012, Taylor et al. Citation2012) did not detect any clear difference. Regarding bi- or unipolar implants, only 1 (Cornell et al. Citation1998) of 5 RCTs found any difference in clinical outcome (Calder et al. Citation1996, Davison et al. Citation2001, Raia et al. Citation2003, Hedbeck et al. Citation2011). The importance of the surgical approach in fracture patients has not, to our knowledge, been studied in any RCT.

As part of the collaboration in the Nordic Arthroplasty Register Association (NARA) (Havelin et al. Citation2009), a common hemiarthroplasty dataset was created based on data from the Norwegian Hip Fracture Register (NHFR) and the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register (SHAR). This dataset has been thoroughly described earlier and revealed differences in implant design, surgical technique, and reoperation rates between the countries (Gjertsen et al. Citation2014). Using this dataset, we have now investigated factors that influence the reoperation rate after hemiarthroplasties in general and due to specific complications.

Material and methods

Both the NHFR and the SHAR began registration of hemiarthroplasties in 2005 (Gjertsen et al. Citation2008, Leonardsson et al. Citation2012a). Verification of data recording in hemiarthroplasties in the NHFR and the SHAR is 99% and 96% (Dale et al. Citation2011, Leonardsson et al. Citation2012a). Both primary procedures and reoperations are registered. In the common database, only hemiarthroplasties for hip fractures were included. By using the unique identification numbers given to all inhabitants of Norway and Sweden, reoperations were linked to their index operation.

Gjertsen et al. (Citation2014) have already described the whole dataset. The 2 national datasets were prepared from the respective registries. A common set of variables was defined and re-coded in order to obtain similar definitions of the variables, resulting in 2 homogeneous databases before merging. De-identification of the patients was done before the 2 datasets were merged. A reoperation was defined as any further open surgery, including open reduction of dislocated HAs and soft tissue reoperations without removal or exchange of prosthesis components. Hospital volume was defined—based on annual number of procedures—as 100 or fewer (“low”) or more than 100 (“high”). The fractures were defined by their ICD-10 codes S72.00 (fracture of neck of femur), S72.10 (peritrochanteric fracture), and S72.20 (subtrochanteric fracture) in the registries. Only 1.1% and 0.3% belonged to the 2 latter groups; a number of these were probably basocervical fractures, and others may have been miscoded. The registries have no access to radiographs for validation of fracture type.

We included all types of proximal femoral fractures in patients who were 60 years and older, from 2005–2010. 183 individuals less than 60 years of age were excluded. Procedures with incomplete registry records and those performed with approaches other than the direct lateral transgluteal approach (Gammer Citation1985, Hardinge Citation1982) or the posterior approach (Moore Citation1957) were excluded (n = 1,028). Monoblock prostheses (n = 1,954) were also excluded, as these are now hardly used in Sweden and Norway; 83% of the registered monoblock implants were used before 2008. From an original dataset of 36,989 procedures, 33,205 were included in the analyses.

Ethics

The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Gothenburg (ref. 1030-11).

Statistics

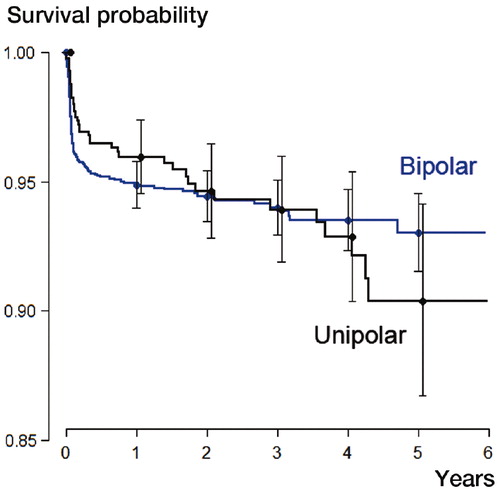

Cox regression analyses on reoperation (generally, and subdivided into the 4 most common reasons for reoperation) were performed with covariates including age group (60–74 years, 75–85 years, and over 85 years), sex, type of stem (uncemented or cemented), type of implant head (unipolar or bipolar), surgical approach, and hospital volume. Hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are presented. A separate Cox regression analysis was carried out including the patients with information on cognitive function (n = 29,340), with dementia as a covariate. “Present” and “uncertain” dementia were grouped together and compared to “none”. Information on dementia was mainly collected from existing medical records or from family members. In addition, both Swedish and Norwegian hip fracture guidelines recommend routine testing for dementia on admission to hospital. The registries are not aware of the extent to which this is actually done. Furthermore, we performed chi-square test and survival analysis (Kaplan-Meier) including use of the log-rank test. The limit for significance was set at p ≤ 0.05. Survival curves were plotted for all covariates, and Schoenfeld residuals were computed and plotted to test the proportional hazards assumption. These analyses showed non-proportionality related to age when reoperation for any reason was used as outcome. We therefore performed 1 analysis for each of the 3 major age groups including sex, type of fixation, type of femoral head, surgical approach, and hospital volume. Type of head (i.e. bipolar or unipolar) was omitted for the age range 60–74 years, due to lack of proportionality (Figure).

PASW Statistics 18 and the R package version 2.13.0 were used for the statistical calculations.

Results

Mean age was 84 (SD 6.7) years and 24,059 patients (72%) were women. 1,164 of the 33,205 patients (3.5%) had been reoperated during a mean follow-up of 2.7 (SD 1.7) years. The most common reasons were dislocation (443 cases), infection (424 cases), and periprosthetic fracture (154 cases). 13 patients had aseptic loosening and 130 were reoperated due to other complications including acetabular erosion ().

Table 1. Crude reoperation rates

Risk factors for reoperation in general

In patients over 85 years (n = 13,828), increased risk of reoperation for any reason was found for male sex and for use of uncemented stems, posterior approach, and bipolar heads (). In patients aged 75–85 years (n = 16,121), male sex and the use of uncemented stems carried an increased risk of reoperation (). In the youngest age group (60–74 years, n = 3,256), no particular risk factors regarding reoperation in general were found (). In this group, head design was omitted due to lack of proportionality (Figure). Regarding trends in crude reoperation rate, this group contrasted with the 2 older ones, as women had a higher crude reoperation rate. 120 of 2,156 women (5.6%) had secondary surgery, as compared to 51 of 1,100 men (4.6 %).

Table 2. Risk factors for reoperation of any kind for different age groups. Cox regression analysis with hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). Head design has been omitted for ages 60–74 years due to lack of proportionality

Risk factors for reoperation for specific reasons

Men had an increased risk of surgery for periprosthetic fracture (). Patients aged 60–74 years had an increased risk of reoperation due to dislocation, infection, and erosion/other complications, compared to the older groups. Uncemented stems were associated with higher risk of reoperation due to periprosthetic fracture, erosion/other complications, and infection. Bipolar heads carried an increased risk of infection and fracture-related reoperation. Posterior approach increased the risk of reoperation due to dislocation and periprosthetic fracture, but reduced the risk of erosion/other complications. Hospital volume only affected the risk of periprosthetic fracture, where an increased risk was seen in larger hospitals.

Table 3. Risk factors for reoperation due to specific complications for all ages. Cox regression analysis with hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI)

The pattern of risk factors for the 3 major complications was mainly the same when we split the population into age groups. For example, in patients over 85 years, the use of uncemented stems turned out to be a risk factor for reoperation due to infection, dislocation, and periprosthetic fracture. In those aged between 75 and 85 years, the use of uncemented stems increased the risk of periprosthetic fracture surgery. Use of a posterior approach was a risk factor for reoperation due to dislocation in all age groups. Male sex was a risk factor for reoperation due to periprosthetic fracture in the 2 older groups. In all age groups, surgery at a low-volume hospital led to a reduced risk of reoperation for periprosthetic fracture ().

Table 4. Risk factors for reoperation due to specific complications for patients in 3 age groups (A–C). Cox regression analysis with hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). Head design has been omitted for ages 60–74 years due to lack of proportionality

Risk factors for reoperation due to erosion

A sub-analysis of reoperation due to acetabular erosion was made in the Swedish patients, since this complication not was specifically recorded in Norway. Of the 22,404 Swedish patients, 49 had a reoperation due to erosion. We found an increased risk of reoperation due to erosion in younger patients (60–74 years: HR = 58, CI: 8–452; 75–85 years: HR = 24, CI: 3–177) and with unipolar heads (HR = 2.5, CI: 1.4–4.6).

Dementia as a risk factor for reoperation

29,340 patients had data on cognitive function. When we added dementia as a covariate in the regression analysis of the entire material, dementia was found to increase the risk of reoperation (HR = 1.2, CI 1.1–1.4). Patients with dementia generally had more open surgery due to dislocation, 149 of 9,694 as compared to 236 of 19,646 (p = 0.02, chi-square test).

Discussion

It should be stressed that the registries depend on thorough reporting of reoperations (open surgery only) from participating hospitals; thus, neither closed reductions of dislocations nor non-surgically treated deep infections were included in the present study. Only a few cases of erosion were recorded in this dataset, suggesting that this is a rare cause of reoperation (particularly in the shorter run). It certainly does not exclude the possibility that erosion per se is a more common complication. The fact that we had data on only 13 cases of aseptic loosening precluded further analysis of this complication.

Dislocation

Posterior approach clearly increased the risk of reoperation due to dislocation. This is supported by clinical studies of fractures patients (Chan et al. Citation1975, Keene and Parker Citation1993, Pajarinen et al. Citation2003, Enocson et al. Citation2008) as well as registry data (Leonardsson et al. Citation2012b).

Infection

The reason for increased risk of reoperation due to infection in younger patients, patients operated with a bipolar head, and those with an uncemented stem is not clear. The older the patient, the greater the tendency might be to prefer non-surgical treatment of infection, such as long-term antibiotic treatment. Younger fracture patients selected to hemiarthroplasty treatment might have comorbidities, making them more susceptible to infection. It is not clear whether the role of polyethylene in a bipolar head (as opposed to an all-metal unipolar head) plays any role, for example an increased reoperation rate due to an ambition to exchange polyethylene parts. Cement loaded with antibiotics is used routinely in Norway and Sweden (CitationEngesaeter et al. 2010, Garellick et al. Citation2012), which could lead to a slightly lower infection rate compared to uncemented stems. A lower risk of revision due to infection has been observed in cemented stems than in uncemented stems, for both primary total hip arthroplasty and hemiarthroplasties (Garellick et al. Citation2012, Gjertsen et al. Citation2012).

Periprosthetic fracture

The increased risk of periprosthetic fracture seen for uncemented stems is well known from registry studies (Graves et al. Citation2009, Leonardsson et al. Citation2009, Leonardsson et al. Citation2012b) and has recently been shown in an RCT as well (Taylor et al. Citation2012). As in a study by CitationLindahl (2006), males were found to have a higher risk of periprosthetic fracture, contradicting the belief that old osteoporotic women are particularly at risk. The men who suffer a hip fracture may represent another type of frailty and propensity to fall. The relationship between posterior approach, large hospital volume, and periprosthetic fracture is difficult to determine. Regarding the latter, large teaching hospitals may experience more complications. In elective THA surgery, the posterior approach has actually been assumed to reduce the fracture risk (Jolles et al. Citation2006). We plan to do an analysis to find on any correlation between mortality and stem fixation in this material.

Acetabular erosion and other complications

This group mainly consisted of patients with erosion and pain of unclear origin. The younger the patient the higher the risk, which is well in line with erosion being related to grade of activity (Baker et al. Citation2006). The higher risk associated with uncemented stems may be attributed to their tendency to give more thigh pain initially, but this has mostly been linked to the Austin-Moore stem, which was not included in this study (Parker et al. Citation2010). The reduced risk after posterior incision might be explained by less extensive dissection and less compromise to the hip abductors than with the lateral approach (Baker et al. Citation1989).

When analyzing erosion only, the cases were few, resulting in wide confidence intervals. We did find the protective effect of a bipolar head that was the hypothesis behind the development of the design. In RCTs, only 1 study has confirmed this, and then only regarding radiological signs of erosion—not clinical symptoms (Hedbeck et al. Citation2011).

Age

The younger the patient is, the higher is the risk of reoperation after hemiarthroplasty, in particular due to dislocation, infection, and erosion. The outcome in the age group 60–75 years differed substantially from that in the older age groups. No clear risk factors could be found, and women had a higher crude reoperation rate than men. Different patient characteristics in the younger group must be suspected. A selection bias is also introduced, as the 2 countries have different treatment regimens for this age group. In Norway, half of the patients were treated with hemiarthroplasties, 14% with a THA, and 36% with internal fixation (IF) (Gjertsen Citation2012). In Sweden, 28% had hemiarthroplasty, as many as 46% had THA, and 26% had IF (Leonardsson et al. Citation2013). In order to compare results internationally, this patient and treatment selection must be known. In Australia, 57% of patients aged between 60 and 75 years are treated with internal fixation, 35% with hemiarthroplasty, and only 8% with THA (Data from the AOA National Joint Replacement Register (personal communication with Ms Ann Tomkins)). In the UK, the rate of THA has been increasing in the last few years (Currie et al. Citation2012). These variations make comparisons of national studies more difficult.

Comparison with other studies

Modern hemiarthroplasties all function reasonably well, and the clinical differences may be minor. Still, given the high number of hip fractures, the impact of these procedures on health economics, and the strain of any reoperation on an elderly individual, it is important to improve the results further. Traditional RCTs have had difficulties in detecting these clinical differences, thus not helping surgeons to choose the best implant. Studying large, prospectively registered data on a national (or international) level complements controlled clinical studies. Apart from being in line with those from the SHAR and NHFR alone (Gjertsen Citation2012, Leonardsson et al. Citation2012b), our findings mainly support the results from the Australian registry (AOANJRR). On the question of bipolar or unipolar heads, though, our results contradict the higher cumulative revision rate after unipolar implants in the AOANJRR. To some extent, this might be due to a different age distribution: 25% of Australian patients treated with bipolar prostheses are under 75 years, as compared to 10% in our study. Corresponding numbers for unipolar prostheses are 19% and 8% (Graves et al. Citation2012). The causality is complex, as shown in the present study. For our oldest group, the use of a bipolar head increased the risk of reoperation. The suggested association between the use of bipolar heads and infection and periprosthetic fracture may be spurious, with unknown confounding factors. Further refinement of registry data and longer follow-up is required to determine whether bipolar heads are of any benefit, more than the reduced risk of acetabular erosion in the youngest group. Our figures suggest that erosion is a rare complication. However, the development of erosion is gradual, and many elderly people may hesitate to seek medical care; instead, they may adapt to a sedentary lifestyle. Thus, the problem of erosion may be considerably underrated when using reoperation as endpoint, as surgeons may hesitate to perform revision surgery in an elderly individual. Age, i.e. activity level, is the main risk factor for development of erosion (Baker et al. Citation2006, Leonardsson et al. Citation2012b).

To summarize, our results on the benefits of unipolar heads must be seen in the light of the fact that in Norway and Sweden, younger patients with femoral neck fractures are to a great extent treated with internal fixation or THA. In addition, a longer follow-up may reveal inferior long-term results for unipolar heads, as suggested by the survival curve for the younger group. Implant choice must be guided by the assumed remaining life of the patient.

Strengths and limitations

In terms of size and as an international joint venture, our material is unique. We chose not to include country in the regression analyses, due to co-variation. Posterior approaches and unipolar heads are seldom used in Norway. In Sweden, cemented implants predominate (Gjertsen et al. Citation2014). A drawback of the project was that only variables used in both registries could be included, and patient characteristics were not known in detail. There may have been unknown confounding factors. A potential selection bias regarding implants and surgical technique at different hospitals may have been compensated for by the fact that all the hospitals in Norway and Sweden contributed.

In addition to reoperation as endpoint, ideally patient-reported outcome and non-surgically treated complications should also be analyzed. Regarding primary surgery, both registries have excellent completeness (96–99%) (Dale et al. Citation2011, Leonardsson et al. Citation2012a). Some hospitals may fail in their routines for reporting reoperations, which have prompted further analysis in both countries. However, we assume that under-reporting may not affect the results systematically. We chose to compare the major principles used in most hospitals, not specific brands of implants. The reoperation rate should be seen as a best-case scenario.

Conclusion

Infection, dislocation, and periprosthetic fracture are the main reasons for failure after hemiarthroplasty surgery. Each complication appears to have a particular risk profile. Use of the direct lateral approach is important in order to prevent dislocation-related reoperations. Cemented stems reduce the risk of periprosthetic fractures and infections. Unipolar heads appear to serve most of the elderly best. Patients aged 60–74 years have an inferior outcome after hemiarthroplasty compared to older patients. If an active patient is treated with hemiarthroplasty, a bipolar head might be beneficial to prevent erosion. The optimum choice of unipolar or bipolar hemiarthroplasty, or total hip arthroplasty, based on patient characteristics must be studied further.

CR and JEG planned the study. AMF was responsible for preparing the common dataset. JEG was responsible for the Norwegian dataset and CR was responsible for the Swedish dataset. CR, JEG, AMF, and JK performed the statistical analyses. CR wrote the manuscript with substantial contributions from all authors, who also participated in data collection and in interpretation of the results.

We thank Anna Sandelin at the Center of Registers in Region Västra Götaland for preparing the Swedish dataset. We also thank the staff of the Norwegian and Swedish registries for their work. Finally, we are grateful to all the surgeons and coordinators who loyally report to the national registries.

No competing interests declared.

- Baker AS, Bitounis VC. Abductor function after total hip replacement. An electromyographic and clinical review. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1989; 71 (1): 47-50.

- Baker RP, Squires B, Gargan MF, Bannister GC. Total hip arthroplasty and hemiarthroplasty in mobile, independent patients with a displaced intracapsular fracture of the femoral neck. A randomized, controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2006; 88 (12): 2583-9.

- Calder SJ, Anderson GH, Jagger C, Harper WM, Gregg PJ. Unipolar or bipolar prosthesis for displaced intracapsular hip fracture in octogenarians: a randomised prospective study. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1996; 78 (3): 391-4.

- Chan RN, Hoskinson J. Thompson prosthesis for fractured neck of femur. A comparison of surgical approaches. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1975; 57 (4): 437-43.

- Cornell CN, Levine D, O’Doherty J, Lyden J. Unipolar versus bipolar hemiarthroplasty for the treatment of femoral neck fractures in the elderly. Clin Orthop 1998; (348): 67-71.

- Currie C, Partridge M, Plant F, Roberts J, Wakeman R, Williams A. The National Hip Fracture Database Annual Report 2012. 2012.

- Dale H, Skramm I, Lower HL, Eriksen HM, Espehaug B, Furnes O, Skjeldestad FE, Havelin LI, Engesaeter LB. Infection after primary hip arthroplasty: a comparison of 3 Norwegian health registers. Acta Orthop 2011; 82 (6): 646-54.

- Davison JN, Calder SJ, Anderson GH, Ward G, Jagger C, Harper WM, Gregg PJ. Treatment for displaced intracapsular fracture of the proximal femur. A prospective, randomised trial in patients aged 65 to 79 years. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2001; 83 (2): 206-12.

- Deangelis JP, Ademi A, Staff I, Lewis CG. Cemented versus uncemented hemiarthroplasty for displaced femoral neck fractures: A prospective randomized trial with early follow-up. J Orthop Trauma 2012; 26 (3): 135-40.

- Engesaeter LB, Furnes O, Havelin LI, Fenstad AM. Rapport, Nasjonalt Kompetensesenter for Leddproteser ISBN 978-82-91847-15-3 Bergen, Norway 2010.

- Enocson A, Tidermark J, Tornkvist H, Lapidus LJ. Dislocation of hemiarthroplasty after femoral neck fracture: better outcome after the anterolateral approach in a prospective cohort study on 739 consecutive hips. Acta Orthop 2008; 79 (2): 211-7.

- Figved W, Opland V, Frihagen F, Jervidalo T, Madsen JE, Nordsletten L. Cemented versus uncemented hemiarthroplasty for displaced femoral neck fractures. Clin Orthop 2009; (467) (9): 2426-35.

- Gammer W. A modified lateroanterior approach in operations for hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop 1985; (199): 169-72.

- Garellick G, Kärrholm J, Rogmark C, Rolfson O, Herberts P. Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register Annual Report 2011. ISBN 978-91-980507-1-4. Gothenburg, Sweden 2012.

- Gjertsen JE. Data from the Norwegian Hip Fracture Register (personal communication) 2012.

- Gjertsen JE, Engesaeter LB, Furnes O, Havelin LI, Steindal K, Vinje T, Fevang JM. The Norwegian Hip Fracture Register: experiences after the first 2 years and 15,576 reported operations. Acta Orthop 2008; 79 (5): 583-93.

- Gjertsen JE, Lie SA, Vinje T, Engesaeter LB, Hallan G, Matre K, Furnes O. More re-operations after uncemented than cemented hemiarthroplasty used in the treatment of displaced fractures of the femoral neck: an observational study of 11,116 hemiarthroplasties from a national register. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2012; 94 (8): 1113-9.

- Gjertsen JE, Fenstad AM, Leonardsson O, Engesaeter LB, Karrholm J, Furnes O, Garellick G, Rogmark C. Hemiarthroplasties after hip fractures in Norway and Sweden; a collaboration between the Norwegian and Swedish national registries. Hip Int 2014; 24 (3): in press.

- Graves S, Davidson D, de Steiger R, Tomkins A. Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry. Annual Report. Adelaide:AOA; 2009. In: http://wwwdmacadelaideeduau/aoanjrr/publicationsjsp 2009.

- Graves S, Davidson D, de Steiger R, Tomkins A. Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry. Annual Report. Adelaide:AOA; 2012. In: http://wwwdmacadelaideeduau/aoanjrr/publicationsjsp 2012.

- Hardinge K. The direct lateral approach to the hip. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1982; 64 (1): 17-9.

- Havelin LI, Fenstad AM, Salomonsson R, Mehnert F, Furnes O, Overgaard S, Pedersen AB, Herberts P, Karrholm J, et al. The Nordic Arthroplasty Register Association: a unique collaboration between 3 national hip arthroplasty registries with 280,201 THRs. Acta Orthop 2009; 80 (4): 393-401.

- Hedbeck CJ, Blomfeldt R, Lapidus G, Tornkvist H, Ponzer S, Tidermark J. Unipolar hemiarthroplasty versus bipolar hemiarthroplasty in the most elderly patients with displaced femoral neck fractures: a randomised, controlled trial. Int Orthop 2011; 35(11): 1703-11.

- Jolles B, Bogoch E. Posterior versus lateral surgical approach for total hip arthroplasty in adults with osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews; 2006. p. CD003828.pub3.

- Keene GS, Parker MJ. Hemiarthroplasty of the hip--the anterior or posterior approach? A comparison of surgical approaches. Injury 1993; 24 (9): 611-3.

- Leonardsson O, Rogmark C, Karrholm J, Akesson K, Garellick G. Outcome after primary and secondary replacement for subcapital fracture of the hip in 10 264 patients. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2009; 91 (5): 595-600.

- Leonardsson O, Garellick G, Karrholm J, Akesson K, Rogmark C. Changes in implant choice and surgical technique for hemiarthroplasty. Acta Orthop 2012a; 83 (1): 7-13.

- Leonardsson O, Karrholm J, Akesson K, Garellick G, Rogmark C. Higher risk of reoperation for bipolar and uncemented hemiarthroplasty. Acta Orthop 2012b; 83 (5): 459-66.

- Leonardsson O, Rolfson O, Hommel A, Garellick G, Akesson K, Rogmark C. Patient-reported outcome after displaced femoral neck fracture. A national survey of 4,467 patients. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2013; 95 (18): 1693-9.

- Lindahl H. The periprosthetic femur fracture. A study from the Swedish National Hip Arthroplasty Register In: Institute of Clinical Sciences, Section for Anesthesiology, Biomaterials and Orthopaedics. Gothenburg University of Gothenburg Sahlgrenska Academy 2006.

- Moore AT. The self-locking metal hip prosthesis. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1957; 39 (4): 811-27.

- Pajarinen J, Savolainen V, Tulikoura I, Lindahl J, Hirvensalo E. Factors predisposing to dislocation of the Thompson hemiarthroplasty: 22 dislocations in 338 patients. Acta Orthop Scand 2003; 74 (1): 45-8.

- Parker MJ, Gurusamy KS, Azegami S. Arthroplasties (with and without bone cement) for proximal femoral fractures in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010(6): CD001706.

- Raia FJ, Chapman CB, Herrera MF, Schweppe MW, Michelsen CB, Rosenwasser MP. Unipolar or bipolar hemiarthroplasty for femoral neck fractures in the elderly? Clin Orthop 2003; (414): 259-65.

- Taylor F, Wright M, Zhu M. Hemiarthroplasty of the hip with and without cement: a randomized clinical trial. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2012; 94 (7): 577-83.