Abstract

Background and purpose — Previous work has shown that despite preventive measures, intraoperative contamination of joint replacements is still common, although most of these patients seem to do well in follow-up of up to 5 years. We analyzed the prevalence and bacteriology of intraoperative contamination of primary joint replacement and assessed whether its presence is related to periprosthetic joint infection (PJI) on long-term follow-up.

Patients and methods — 49 primary total hip replacements (THRs) and 41 total knee replacements (TKRs) performed between 1990 and 1991 were included in the study. 4 bacterial swabs were collected intraoperatively during each procedure. Patients were followed up for joint-related complications until March 2011.

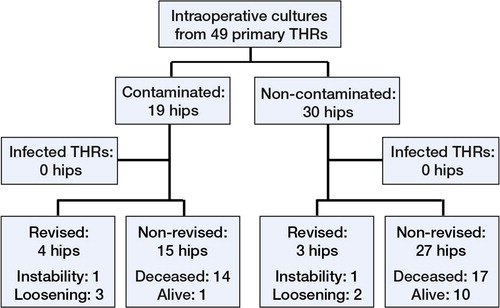

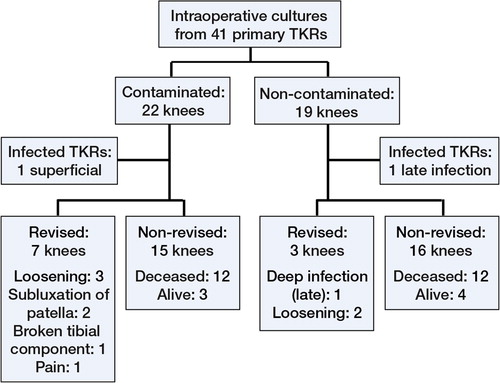

Results — 19 of 49 THRs and 22 of 41 TKRs had at least 1 positive culture. Coagulase-negative staphylococci and Staphylococcus aureus were the most common organisms, contaminating 28 and 9 operations respectively. Where information was available, bacteria from 27 of 29 contaminated operations were susceptible to the prophylactic antibiotic administered. 13% of samples gathered before 130 min of surgery were contaminated, as compared to 35% collected after that time. 2 infections were diagnosed, both in TKRs. 1 of them may have been related to intraoperative contamination.

Interpretation — Intraoperative contamination was common but few infections occurred, possibly due to the effect of prophylactic antibiotics. The rate of contamination was higher with longer duration of surgery. It appears that positive results from intraoperative swabs do not predict the occurrence of PJI.

Periprosthetic joint infection (PJI) is a major complication of joint replacement. 1 year after primary total joint replacement, around 1% of patients have been revised due to deep infection; superficial surgical site infections (SSIs) are more common and occur in around 3% of cases (Jämsen et al. Citation2010, Dale et al. Citation2011). PJI is difficult to diagnose and treat and has a severe effect on quality of life (Whitehouse et al. Citation2002). The number of primary joint replacements will increase (Kurtz et al. Citation2007), so the incidence of PJI may also rise. Prevention is of key importance. Measures such as laminar air flow and prophylactic antibiotics are effective (Lidwell et al. Citation1987). Intraoperative contamination is, however, common—occurring in one-fifth to two-thirds of operations. However, the short-term prognosis of most of these patients appears to be good (Davis et al. Citation1999, Byrne et al. Citation2007). Intraoperative contamination is usually the cause of early infections, but it may also cause a substantial number of the infections arising more than 2 years after surgery (Phillips et al. Citation2006). To our knowledge, there have been no studies on intraoperative contamination with over 5 years of follow-up.

We studied the prevalence and bacteriology of intraoperative contamination during primary joint replacement and assessed whether the presence of intraoperative contamination is related to PJI on long-term follow-up.

Patients and methods

Patients

We collected intraoperative bacterial samples from 92 consecutive primary total hip replacements (THRs) and knee replacements (TKRs) that were carried out for osteoarthritis between October 1990 and September 1991. The sampling was part of a quality-control project evaluating antiseptic routines and ventilation of the operating rooms. Follow-up was until March 1, 2011 unless death or revision had occurred. We did not include patients with less than 1 year of follow-up, which led to the exclusion of 1 THR patient who was revised due to instability and 1 TKR patient who was operated for a distal femur fracture. Neither patient had signs of infection at revision or developed infection afterwards. The study therefore involved 49 THRs (47 patients) and 41 TKRs (40 patients).

Hospital files were reviewed retrospectively for the occurrence of superficial surgical site infection, PJI, or revision. During the follow-up period, revisions were performed at 3 hospitals in Iceland with the 2 largest performing the majority, and we reviewed the medical files of both of them; 1 of these was the hospital in which the study was performed. The patients would most probably have sought medical attention at these 2 largest hospitals for geographical reasons—or have been transferred there in the unlikely event of a PJI being diagnosed elsewhere.

Perioperative treatment and surgical technique

6 orthopedic surgeons at Reykjavik City Hospital, Iceland, performed the operations. The skin was prepared with 2 Hibiscrub showers on the night before and on the morning of surgery, but final preparation was done in the operating room by non-scrubbed personnel wearing sterile gloves. The scrubbed surgical team, which included a scrub nurse, a surgeon, and an assistant who all wore reusable impervious drapes and double gloves, applied disposable impervious skin drapes around the surgical field.

According to surgeon preference, either intravenous cloxacillin (2 g) or cefazolin (1.5 g) was given as infection prophylaxis within 1 h of placing the incision, with continuation at 6- or 8-h intervals (respectively) for 48 h. If there was penicillin allergy, clindamycin (600 mg) was given at 8-h intervals.

Operations were performed in non-laminar airflow operating rooms with positive pressure ventilation (12 changes of air per hour and filters with over 95% average atmospheric dust spot efficiency). In all THRs, a posterior approach was used to implant a Charnley hip prosthesis, except for 4 operations in which Charnley Elite prostheses were used (both from DePuy International, Leeds, UK). For TKR, the Kinematic condylar knee (Howmedica, Rutherford, NJ, USA) was implanted through a medial parapatellar approach. A splash basin was used to store instruments in sterile water when they were not in use. The implants were fixed to bone using gentamicin-impregnated Palacos bone cement (Heraeus Medical, Hanau, Germany).

All patients received thrombosis prophylaxis: 40 mg enoxaparin administered once daily for 7 days or intravenous Macrodex for 3 days. The wound was examined on postoperative days 1 and 5 and any infection was documented. Routine follow-up was at 2 weeks and 3 months postoperatively. There was no prospective infection surveillance program.

Microbiology

In THRs, samples were taken from the acetabulum before and after cementing the cup and from the fascia after its closure; in TKRs, they were taken from the intercondylar notch before and after cementing and from the capsule after its closure. These samples were defined as coming from the wound. In both THRs and TKRs, a sample was taken from the splash basin at the same time as the sample from the fascia or capsule. We decided to take cultures from the 4 sites where we believed contamination could be relevant for the development of infection.

Swabs were immediately placed in Amies transport medium (BD diagnostics, Sparks, MD) and delivered to the laboratory. The material was incubated for 5 days at 36°C on blood agar (aerobically and anaerobically), on chocolate agar, and in thioglycollate broth. Isolated organisms were identified by standard laboratory methods. Contamination was defined as any bacterial growth. Contaminated patients did not receive prolonged antibiotic treatment.

Statistics

To determine statistically significant differences in continuous variables between groups, we used the Wilcoxon rank-sum test with continuity correction. For categorical variables, we used Fisher’s exact test. Prosthesis survival was calculated with the Kaplan-Meier method and survival rates were compared with the log-rank test. Revision was defined as removal or exchange of 1 or more components. Any p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. We used Microsoft Excel and the R software package version 3.0.0 for analysis.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Icelandic National Bioethics Committee and Data Protection Authority on November 20, 2010 (reference number VSNb2010110032/03.7).

Results

19 of 49 THR operations and 22 of 41 TKR operations showed contamination. In 3 THR operations and 7 TKR operations, more than 1 site was contaminated. Coagulase-negative staphylococci (CNS) were the most common contaminating organisms, followed by Staphylococcus aureus (). The splash basin was the most commonly contaminated site ().

Table 1. Contaminating organisms and number of contaminated sites

Table 2. Sites of contamination and duration of surgery at sample collection

When we analyzed THRs and TKRs together, the only demographic or perioperative variable with a statistically significant difference between contaminated and uncontaminated operations was the distribution of type of prophylactic antibiotic administered (p = 0.02) ().

Table 3. Demographic and perioperative variables

Duration of surgery at sample collection

The duration of surgery at sample acquisition was available for 321 (93%) of the 346 samples that we had gathered. 13% of samples gathered before 130 min of surgery were contaminated (39 of 301) as compared to 35% of those collected after that time (7 of 20) (p = 0.01).

Susceptibility of contaminating bacteria to prophylactic antibiotics

Information on antibiotic susceptibility was available for 29 of 41 contaminated operations. The contaminating bacteria were sensitive to the antibiotic that had been administered for the particular procedure in all but 2 cases. 1 was a resistant strain of Staphylococcus species cultured during a TKR, and the other was a CNS with intermediate sensitivity cultured during a THR. Cloxacillin had been administered before both procedures. The THR patient had no postoperative complications but the TKR patient had chronic pain without any clear signs of infection. The knee was revised after 5 years due to a broken tibia component. Cultures were negative at revision.

Outcome

The median follow-up of THRs and TKRs was 15 (1–20) years and 11 (1–20) years. 1 superficial surgical site infection was observed in the TKR group. The knee gave way a few days after surgery, and the wound opened and a superficial infection developed. The wound was revised and resutured, and the patient was treated with antibiotics. Cultures showed CNS, which was also cultured from the intercondylar area before cementing. The patient continued to have pain, and the knee was revised after 2.3 years but was not found to be infected. 1 deep TKR infection arose late following arthrocentesis for traumatic hemarthrosis. This knee, which was in the uncontaminated group, was revised 8 years after the primary operation.

There were 7 revisions in the THR group and 10 in the TKR group; the most common indication was aseptic loosening ( and ).

For THRs, Kaplan-Meier estimated survival after 19 years with revision for any reason as endpoint was 81% (95% CI: 69–95). For TKR, the survival was 69% after 15 years (95% CI: 55–88). There was no statistically significant difference between survival of contaminated and uncontaminated operations when we analyzed THRs and TKRs together, with either revision for any reason or aseptic loosening as endpoint.

Discussion

Our main finding is that although intraoperative contamination was common, we did not find it to be correlated to obvious infection on long-term follow-up. Furthermore, we found that the rate of contamination was higher after longer duration of surgery.

Almost half of our 90 operations had contamination, which is higher than the 23% reported by Byrne et al. (Citation2007) but lower than the 63% reported by Davis et al. (Citation1999). The wide range of contamination reported may be explained by differences in potential risk factors for intraoperative contamination, such as higher number of operating room personnel, longer operation times (Byrne et al. Citation2007), or high BMI (Font-Vizcarra et al. Citation2011). Other patient-, perioperative-, and culture-related factors such as the number of cultures taken, the timing, the site of sampling, and the sensitivity of culture methods might also contribute to the variation in the contamination rates reported.

The splash basin was the most commonly contaminated site. 2 previous studies, where water taken from the splash basin was passed through a grid membrane and the membrane filter was then cultured, gave contamination rates of 74% (Baird et al. Citation1984) and 24% (Anto et al. Citation2006). A recent study in which swabs were used to take cultures from the splash basin found a contamination rate of only 2% (Glait et al. Citation2011), and the authors speculated that the discrepancy might be partly due to differences in sampling methods—but our findings do not support this. To our knowledge, there have been no studies that have clearly linked the splash basin to infection. We nevertheless feel that it should be used with caution, as it appears to be a reservoir for bacteria.

The difference in distribution of type of prophylactic antibiotic administered was statistically significant between contaminated and uncontaminated operations. This finding should be interpreted with great caution, as it is based on few observations—and in light of a systematic review by AlBuhairan et al. (Citation2008), which showed that there is no evidence that any type of antibiotic prophylaxis has better results than any other.

Maathuis et al. (Citation2005) reasoned that contamination of the future prosthesis site might be of more relevance than contamination of remote objects such as light handles and knives, which some studies have reported. They found that the acetabular bed was contaminated in 5 of 67 operations, as compared to 2 of 45 in our study.

Contamination of the fascia and subcutaneous tissue might also be important as a potential source of bacteria causing superficial surgical site infection, which is a known risk factor for PJI (Berbari et al. Citation1998). In our study, the fascia was contaminated in 14 of 87 procedures as compared to 9 of 154 in a study by Frank et al. (Citation2011). In that study, however, the subcutaneous tissue was wiped with an antiseptic before sampling, which may have contributed to the lower contamination rate. That study found that positive cultures were not a reliable predictor of PJI.

Staphylococci were the most commonly isolated organisms, which is in line with previous studies on intraoperative contamination, surgical site infection, and deep infections (Davis et al. Citation1999, Abudu et al. Citation2002, Phillips et al. Citation2006). Causality might be inferred from these observations, and Knobben et al. (Citation2006) concluded that there was an association between intraoperative contamination and PJI but the positive predictive value of intraoperative contamination for PJI was only 14%, becoming 25% if the occurrence of prolonged discharge was added as a criterion.

We found that 13% of samples acquired before 130 min of operative time were positive as compared to 35% if collected after that time point. Byrne et al. (Citation2007) previously found a similar trend, with a cutoff at 90 min. Our results are in accordance with previous work that showed that the risk of infection increases if the duration of surgery exceeds 2–2.5 h (Peersman et al. Citation2001, Ridgeway et al. Citation2005, Dale et al. Citation2009).

41 of our 90 operations were contaminated, yet only 2 infections occurred, both in TKRs. The late infection was probably caused by direct inoculation in relation to arthrocentesis. The superficial infection could have been caused by inoculation through the wound, which ruptured shortly after the primary operation. However, intraoperative contamination cannot be excluded, as CNS were cultured from the primary operation and at revision of the infected wound. Unfortunately, we do not have information on the strain. Previous studies have also found that intraoperative contamination is common even though most of these patients do not develop deep infections ().

Table 4. Previous studies on intraoperative contamination and PJI that reported the number of operations with contamination and that had follow-up

How can this be explained? Firstly, the occurrence of infection is probably determined by the interplay between numerous factors that affect the balance between host defenses and the virulence of the attacking bacteria, and the presence of contamination is only one of them. With a larger study group and more data available, a multivariate analysis could define the independent effect of intraoperative contamination.

Secondly, it is plausible that prophylactic antibiotics contribute, as they have been shown to reduce the relative risk of infection by 81% compared with no prophylaxis (AlBuhairan et al. Citation2008) and most of the contaminating bacteria in our study were susceptible to the antibiotic that had been given prophylactically.

Finally, the size of the inoculum is of importance. In a TKR model in rabbits, the incidence of infection increased with the size of the inoculum (Craig et al. Citation2005). Similarly to previous studies, we determined only the presence or absence of contamination in a couple of small areas in the wound at certain points of time. It is uncertain whether this is a valid method to determine the true load of bacteria in the wound, and potentially affects the relationship between contamination and infection.

There was no statistically significant difference in survival between contaminated and uncontaminated operations. On the other hand, the overall survival of the Kinematic condylar knee, 69% at 15 years, was poorer than the previously reported range of 82–93% at around 15 years (van Loon et al. Citation2000, Gill and Joshi Citation2001). Breakage of the medial part of the metal tibia tray occurred in 3 of 41 TKRs. The highest previously reported occurrence of this failure mechanism of the Kinematic condylar knee prosthesis is 2% (Abernethy et al. Citation1996). Breakage of the tibia component was therefore relatively common in our series, but apart from that we do not have explanations for the poor survival rate. The survival of Charnley prostheses was 81% at 19 years, which is similar to previously reported rates of 82% (Klapach et al. Citation2001) and 84% (Berry et al. Citation2002) at 20 years.

The present study had a number of weaknesses. It was not possible to analyze the relationship between intraoperative contamination and infection, as only 2 infections occurred and only 1 of them might have been caused by intraoperative contamination. This relates to the small size of the study group, as the rate of infections was within the previously reported range of 1–3%.

Other weaknesses included lack of control swabs and information on the timing of administration of prophylactic antibiotics preoperatively. It is probably most effective if given within 30 minutes of placing the incision (van Kasteren et al. Citation2007). We incubated cultures for 5 days, which is the same period of time most commonly reported for diagnosing PJI (Butler-Wu et al. Citation2011). However, Schäfer et al. (Citation2008) found that 26% of cases defined as PJI on the basis of culture results after 14 days had been negative after 7 days of incubation. Furthermore, a recent study by Aggerwal et al. (2013) found that tissue cultures were more sensitive and specific than swabs in the diagnosis of PJI. Considering these results, it is therefore possible that we did not identify all the contaminated operations.

We are confident that we managed to find the majority of patients who were revised, despite the retrospective nature of the study. Some infections could have been treated with antibiotics without revision, but due to the small size of our community it is likely that such patients would have attended the outpatient department at some point, but we found no such patients.

We cannot make conclusions about the relationship between intraoperative contamination and PJI. However, positive bacterial swabs from primary joint replacements using the current methodology did not predict the occurrence of deep infection during long-term follow-up and they are therefore not helpful in identifying patients at risk of PJI. Nevertheless, contamination is common, with the possibility of causing infection. This should encourage us to adhere meticulously to antiseptic routines, especially as the incidence of PJI might be rising (Dale et al. Citation2012)—possibly due in part to declining preventive routines (Stefánsdóttir et al. Citation2009). Furthermore, the rate of contamination was higher with longer duration of surgery, which should be avoided.

EJ: contributed to data collection, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript. HJ: collected data. OR: supervised the analysis and wrote the manuscript. BM: planned the study and supervised data collection and analysis. All the authors contributed to editing and revision of the manuscript.

We thank Magnus Gottfredsson MD, Department of Infectious Diseases, Landspitali University Hospital, Reykjavik for advice during writing of the manuscript.

No competing interests declared.

- Abernethy PJ, Robinson CM, Fowler RM. Fracture of the metal tibial tray after Kinematic total knee replacement. A common cause of early aseptic failure. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1996; 78 (2): 220-5.

- Abudu A, Sivardeen KA, Grimer RJ, Pynsent PB, Noy M. The outcome of perioperative wound infection after total hip and knee arthroplasty. Int Orthop 2002; 26 (1): 40-3.

- Aggarwal VK, Higuera C, Deirmengian G, Parvizi J, Austin MS. Swab cultures are not as effective as tissue cultures for diagnosis of periprosthetic joint infection. Clin Orthop 2013; (471) (10): 3196-203.

- AlBuhairan B, Hind D, Hutchinson A. Antibiotic prophylaxis for wound infections in total joint arthroplasty: a systematic review. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2008; 90 (7): 915-9.

- Anto B, McCabe J, Kelly S, Morris S, Rynn L, Corbett-Feeney G. Splash basin bacterial contamination during elective arthroplasty. J Infect 2006; 52 (3): 231-2.

- Baird RA, Nickel FR, Thrupp LD, Rucker S, Hawkins B. Splash basin contamination in orthopaedic surgery. Clin Orthop 1984; (187): 129-33.

- Berbari EF, Hanssen AD, Duffy MC, Steckelberg JM, Ilstrup DM, Harmsen WS, et al. Risk factors for prosthetic joint infection: case-control study. Clin Infect Dis 1998; 27 (5): 1247-54.

- Berry DJ, Harmsen WS, Cabanela ME, Morrey BF. Twenty-five-year survivorship of two thousand consecutive primary Charnley total hip replacements: factors affecting survivorship of acetabular and femoral components. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2002; 84 (2): 171-7.

- Butler-Wu SM, Burns EM, Pottinger PS, Magaret AS, Rakeman JL, Matsen FA, 3rd, et al. Optimization of periprosthetic culture for diagnosis of Propionibacterium acnes prosthetic joint infection. J Clin Microbiol 2011; 49 (7): 2490-5.

- Byrne AM, Morris S, McCarthy T, Quinlan W, O’Byrne JM. Outcome following deep wound contamination in cemented arthroplasty. Int Orthop 2007; 31 (1): 27-31.

- Craig MR, Poelstra KA, Sherrell JC, Kwon MS, Belzile EL, Brown TE. A novel total knee arthroplasty infection model in rabbits. J Orthop Res 2005; 23 (5): 1100-4.

- Dale H, Hallan G, Espehaug B, Havelin LI, Engesæter LB. Increasing risk of revision due to deep infection after hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthop 2009; 80 (6): 639-45.

- Dale H, Skråmm I, Løwer HL, Eriksen HM, Espehaug B, Furnes O, et al. Infection after primary hip arthroplasty: a comparison of 3 Norwegian health registers. Acta Orthop 2011; 82 (6): 646-54.

- Dale H, Fenstad AM, Hallan G, Havelin LI, Furnes O, Overgaard S, et al. Increasing risk of prosthetic joint infection after total hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthop 2012; 83 (5): 449-58.

- Davis N, Curry A, Gambhir AK, Panigrahi H, Walker CR, Wilkins EG, et al. Intraoperative bacterial contamination in operations for joint replacement. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1999; 81 (5): 886-9.

- Font-Vizcarra L, Tornero E, Bori G, Bosch J, Mensa J, Soriano A. Relationship between intraoperative cultures during hip arthroplasty, obesity, and the risk of early prosthetic joint infection: a prospective study of 428 patients. Int J Artif Organs 2011; 34 (9): 870-5.

- Frank CB, Adams M, Kroeber M, Wentzensen A, Heppert V, Schulte-Bockholt D, et al. Intraoperative subcutaneous wound closing culture sample: a predicting factor for periprosthetic infection after hip- and knee-replacement? Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2011; 131 (10): 1389-96.

- Gill GS, Joshi AB. Long-term results of Kinematic Condylar knee replacement. An analysis of 404 knees. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2001; 83 (3): 355-8.

- Glait SA, Schwarzkopf R, Gould S, Bosco J, Slover J. Is repetitive intraoperative splash basin use a source of bacterial contamination in total joint replacement? Orthopedics 2011; 34 (9): e546-9.

- Jämsen E, Varonen M, Huhtala H, Lehto MU, Lumio J, Konttinen YT, et al. Incidence of prosthetic joint infections after primary knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2010; 25 (1): 87-92.

- Klapach AS, Callaghan JJ, Goetz DD, Olejniczak JP, Johnston RC. Charnley total hip arthroplasty with use of improved cementing techniques: a minimum twenty-year follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2001; 83 (12): 1840-8.

- Knobben BA, Engelsma Y, Neut D, van der Mei HC, Busscher HJ, van Horn JR. Intraoperative contamination influences wound discharge and periprosthetic infection. Clin Orthop 2006; (452): 236-41.

- Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, Mowat F, Halpern M. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2007; 89 (4): 780-5.

- Lidwell OM, Elson RA, Lowbury EJ, Whyte W, Blowers R, Stanley SJ, et al. Ultraclean air and antibiotics for prevention of postoperative infection. A multicenter study of 8,052 joint replacement operations. Acta Orthop Scand 1987; 58 (1): 4-13.

- Maathuis PG, Neut D, Busscher HJ, van der Mei HC, van Horn JR. Perioperative contamination in primary total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop 2005; (433): 136-9.

- Peersman G, Laskin R, Davis J, Peterson M. Infection in total knee replacement: a retrospective review of 6489 total knee replacements. Clin Orthop 2001; (392): 15-23.

- Phillips JE, Crane TP, Noy M, Elliott TS, Grimer RJ. The incidence of deep prosthetic infections in a specialist orthopaedic hospital: a 15-year prospective survey. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2006; 88 (7): 943-8.

- Ridgeway S, Wilson J, Charlet A, Kafatos G, Pearson A, Coello R. Infection of the surgical site after arthroplasty of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2005; 87 (6): 844-50.

- Schäfer P, Fink B, Sandow D, Margull A, Berger I, Frommelt L. Prolonged bacterial culture to identify late periprosthetic joint infection: a promising strategy. Clin Infect Dis 2008; 47 (11): 1403-9.

- Stefánsdóttir A, Robertsson O, W-Dahl A, Kiernan S, Gustafson P, Lidgren L. Inadequate timing of prophylactic antibiotics in orthopedic surgery. We can do better. Acta Orthop 2009; 80 (6): 633-8.

- van Kasteren ME, Manniën J, Ott A, Kullberg BJ, de Boer AS, Gyssens IC. Antibiotic prophylaxis and the risk of surgical site infections following total hip arthroplasty: timely administration is the most important factor. Clin Infect Dis 2007; 44 (7): 921-7.

- van Loon CJ, Wisse MA, de Waal Malefijt MC, Jansen RH, Veth RP. The kinematic total knee arthroplasty. A 10- to 15-year follow-up and survival analysis. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2000; 120 (1-2): 48-52.

- Whitehouse JD, Friedman ND, Kirkland KB, Richardson WJ, Sexton DJ. The impact of surgical-site infections following orthopedic surgery at a community hospital and a university hospital: adverse quality of life, excess length of stay, and extra cost. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2002; 23 (4): 183-9.