Abstract

Background — Ancient Egypt might be considered the cradle of medicine. The modern literature is, however, sometimes rather too enthusiastic regarding the procedures that are attributed an Egyptian origin. I briefly present and analyze the claims regarding orthopedic surgery in Egypt, what was actually done by the Egyptians, and what may have been incorrectly ascribed to them.

Methods — I reviewed the original sources and also the modern literature regarding surgery in ancient Egypt, concentrating especially on orthopedic surgery.

Results — As is well known, both literary sources and the archaeological/osteological material bear witness to treatment of various fractures. The Egyptian painting, often claimed to depict the reduction of a dislocated shoulder according to Kocher’s method, is, however, open to interpretation. Therapeutic amputations are never depicted or mentioned in the literary sources, while the specimens suggested to demonstrate such amputations are not convincing.

Interpretation — The ancient Egyptians certainly treated fractures of various kinds, and with varying degrees of success. Concerning the reductions of dislocated joints and therapeutic amputations, there is no clear evidence for the existence of such procedures. It would, however, be surprising if dislocations were not treated, even though they have not left traces in the surviving sources. Concerning amputations, the general level of Egyptian surgery makes it unlikely that limb amputations were done, even if they may possibly have been performed under extraordinary circumstances.

The art of medicine might be said to have first seen the light of day in Egypt, and the Egyptian doctors were well respected and sought after by foreign rulers (Herodotus Citation1890, von Staden Citation1989). However, I can mention here the Egyptian physicians of the Persian king Darius, who were sentenced to impalement for their failure to cure his ankle dislocation. Their lives and the ankle of Darius had to be saved by a Greek.

The high regard for the ancient Egyptians remained through the ages and the Napoleonic expedition to Egypt at the end of the eighteenth century with the birth of modern Egyptology contributed considerably to the interest, admiration, and not least to the romantic air surrounding the alleged skills of the ancient Egyptians, which to some extent still persist today.

However, even though Egypt may be considered to be the cradle of medicine, the modern literature is sometimes too enthusiastic. Procedures such as cataract surgery (Ascaso et al. Citation2009, Blomstedt Citation2014), trephinations (El Gindi Citation2002, Blomstedt Citation2012), tracheostomies (Vikentiev Citation1949–1950, Blomstedt Citation2014), dental surgery (Weinberger Citation1947, Blomstedt Citation2013), etc. have often, but incorrectly, been considered to be of Egyptian origin. Such statements have been published in respected international peer-reviewed publications, and can be found throughout the literature. This is also true in the field of orthopedic surgery, or more specifically regarding reductions of dislocated shoulders, and especially concerning amputations, which have often been given a place in the armamentarium of the Egyptian doctors.

In an attempt to provide a critical and balanced image of the surgical skills of the ancient Egyptians, I have reviewed the original sources and the modern literature regarding the different areas of surgery.

I briefly present and analyze the claims regarding orthopedic surgery in Egypt, from the first dynasty (ca. 3,100 BC) until the beginning of the Ptolemaic era (332 BC), in order to establish what the Egyptians actually did and what has been incorrectly ascribed to them.

Orthopedic surgery in ancient Egypt

The existence of different specialties in the field of medicine is well known from ancient Egypt, such as what we today would refer to as ophthalmology or dentistry. Contrary to what has sometimes been stated (Ebbell Citation1937), there are, however, no indications that surgery was one of these, or that it was seen as separate from the field of medicine in general (Jonckheere Citation1951a, b), and the same is of course true regarding orthopedic surgery. Orthopedic conditions and treatments have, however, been documented in the Egyptian material.

Fractures

Our main source of knowledge regarding surgery in Egypt is the preserved medical papyri, but only one of these—the Edwin Smith papyrus—is of interest concerning orthopedic surgery. The preserved copy of this papyrus is dated to the New Kingdom, around 1,300 BC, but it is possible that this work originated from an earlier period. The 48 case presentations are divided into title, examination, diagnosis/prognosis, and treatment, and in several cases there is a vocabulary with explanations. For each case, it is decided whether it is a condition to treat, to contend, or not to treat due to a poor prognosis. The cases are arranged systematically beginning with the skull and progressing downwards. For some unknown reason, the scribe has stopped in the middle of a word, in the middle of a case, in the middle of the text. It seems natural that the original manuscript would have continued all the way down to the feet, but unfortunately there is no case involving the pelvic area or the lower extremities.

Cases 29–33 and 48 deal with injuries to the spinal column, but are of limited interest since the orthopedic nature of these cases is limited to the conditions, and not to the treatment, which is either non-existent or of a purely non-surgical nature. The cases of most interest regarding what we would consider to be orthopedic surgery today are cases 34–38, which I present here in some detail.

Concerning case 34, dislocation of the 2 clavicles, it is not clear whether we are dealing with a trauma of one or both clavicles. While the linguistics are in favor of the latter, it seems more likely that we are dealing with the former on probabilistic grounds and that it can be assumed to be a sterno-clavicular dislocation. This condition is treated with a reduction and binding with stiff rolls of linen:

“If thou examinest a man having a dislocation in his two collar-bones, shouldst thou find his two shoulders turned over, (and) the head(s) of his two collar-bones turned toward his face.”

“Thou shouldst cause (them) to fall back, so that they rest in their places. Thou shouldst bind it with stiff rolls of linen; thou shouldst treat it afterward [with] grease (and) honey every day, until he recovers.” (Breasted Citation1930).

In an alternative scenario in case 34, there is a rupture in the overlying tissue. This is said to be a case to be treated. No treatment is suggested, however, and this is likely to be a scribal error where the original verdict would have been a case not to treat (Breasted Citation1930). The text continues with a description of a clavicular fracture in case 35, which receives the following treatment:

“Thou shouldst place him prostrate on his back, with something folded between his two shoulder-blades; thou shouldst spread out with his two shoulders in order to stretch apart his collar-bone until that break falls into its place. Thou shouldst make for him two splints of linen, (and) thou shouldst apply one of them both on the inside of his upper arm and the other on the under side of his upper arm. Thou shouldst bind it with ymrw, (and) treat it afterward with honey every day, until he recovers.” (Breasted Citation1930)

From the description, it is unclear how the suggested splint would have exerted its effect, and the same treatment is suggested almost word for word in case 36, a fracture of the humerus. Considering the different techniques necessary for reduction and for stabilization of these cases, we must be dealing here with a scribal error. Perhaps we might assume that while the reduction belongs to case 35, the splints have originally been part of the treatment of the humerus fracture. Splints are also mentioned in case 37, a fracture of the humerus with a rupture of the overlying tissue. A case to be contended, according to the following:

“If thou examinest a man having a break in his upper arm, over which a wound has been inflicted, (and) thou findest that that break crepitates under thy fingers.

Thou shouldst make for him two splints of linen; thou shouldst bind it with ymrw; (and) thou shouldst treat it afterwards [with] grease, honey, (and) lint every day until thou knowest that he has reached a decisive point.” (Breasted Citation1930).

A second case is also described with a more serious wound “piercing through to the interior of his injury”, a case not to be treated. Perhaps in the first case the skin was not penetrated by the fracture, or perhaps we are dealing here with wounds afflicted from the outside with different depths of penetration (Brorson Citation2009). The last case (38) is a mere split in the humerus. A split in this particular case was most probably conceived as a minor stable skeletal injury without dislocation.

Concerning various fractures, the abundant osteological material has demonstrated many cases of fracture healing in good position, while the opposite has also been frequent (Said Citation2002). Well-healed fractures have sometimes been taken as evidence of skilled bone setters (Jäger Citation1907, Citation1909). However, most fractures heal well in primates, including humans, without access to orthopedic treatment (Schultz Citation1944, Ackerknecht Citation1947).

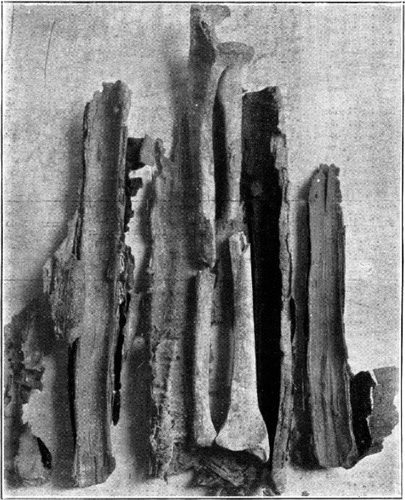

2 graves from the fifth dynasty have also been found in Naga-ed-dêr with preserved wooden splints in situ, where the patients apparently died due to open fractures (Smith Citation1908). The splints seem to have been of an efficient design concerning the fracture of the forearm (), while the same cannot be said regarding the fracture of the femur ().

Figure 1. Compound fracture of the forearm with unwrapped bark splints. From Smith (Citation1908).

Figure 2. Compound fracture of the femur with wooden splints in situ. From Smith (Citation1908).

Reduction of dislocated shoulder

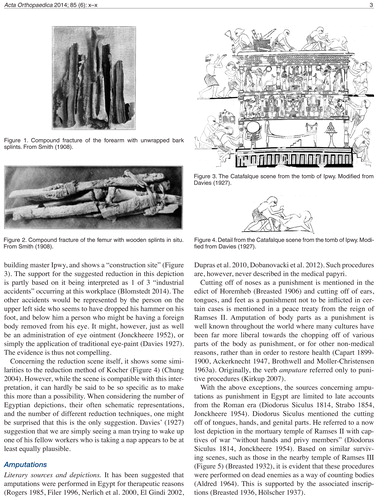

Reduction of a dislocated jaw is described in the Edwin Smith papyrus, but reduction of dislocated limbs is never mentioned in the literary sources. It seems, however, to be commonly accepted that the first evidence regarding reduction of a dislocated shoulder dates back to ancient Egypt, normally specified as a depiction in the tomb of Ipwy (Hussein Citation1965-1966, Filer Citation1996, Mattick and Wyatt Citation2000, Colton Citation2013). The scene is suggested to represent reduction of a dislocated shoulder and has been adopted as the emblem of the Egyptian Orthopedic Association (Said Citation2002). It was found in the tomb of the building master Ipwy, and shows a “construction site” (). The support for the suggested reduction in this depiction is partly based on it being interpreted as 1 of 3 “industrial accidents” occurring at this workplace (Blomstedt Citation2014). The other accidents would be represented by the person on the upper left side who seems to have dropped his hammer on his foot, and below him a person who might be having a foreign body removed from his eye. It might, however, just as well be an administration of eye ointment (Jonckheere Citation1952), or simply the application of traditional eye-paint (Davies Citation1927). The evidence is thus not compelling.

Figure 3. The Catafalque scene from the tomb of Ipwy. Modified from Davies (Citation1927).

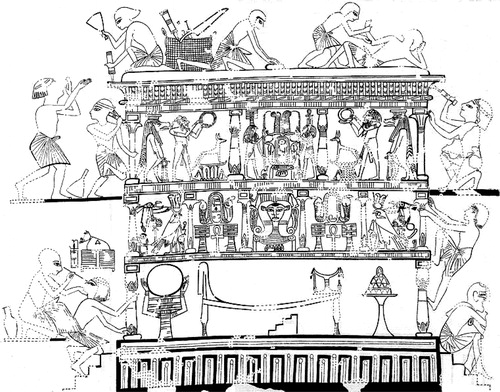

Concerning the reduction scene itself, it shows some similarities to the reduction method of Kocher () (Chung Citation2004). However, while the scene is compatible with this interpretation, it can hardly be said to be so specific as to make this more than a possibility. When considering the number of Egyptian depictions, their often schematic representations, and the number of different reduction techniques, one might be surprised that this is the only suggestion. Davies’ (Citation1927) suggestion that we are simply seeing a man trying to wake up one of his fellow workers who is taking a nap appears to be at least equally plausible.

Figure 4. Detail from the Catafalque scene from the tomb of Ipwy. Modified from Davies (Citation1927).

Amputations

Literary sources and depictions. It has been suggested that amputations were performed in Egypt for therapeutic reasons (Rogers Citation1985, Filer Citation1996, Nerlich et al. Citation2000, El Gindi Citation2002, Dupras et al. Citation2010, Dobanovacki et al. Citation2012). Such procedures are, however, never described in the medical papyri.

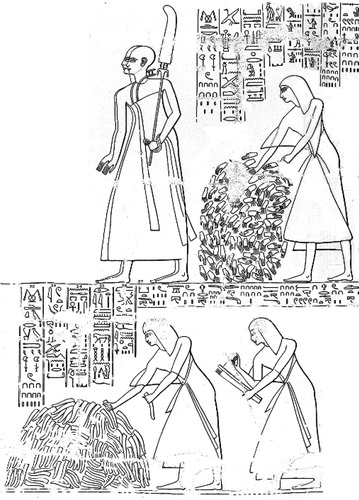

Cutting off of noses as a punishment is mentioned in the edict of Horemheb (Breasted Citation1906) and cutting off of ears, tongues, and feet as a punishment not to be inflicted in certain cases is mentioned in a peace treaty from the reign of Ramses II. Amputation of body parts as a punishment is well known throughout the world where many cultures have been far more liberal towards the chopping off of various parts of the body as punishment, or for other non-medical reasons, rather than in order to restore health (Capart Citation1899-1900, Ackerknecht Citation1947, Brothwell and Moller-Christensen Citation1963a). Originally, the verb amputare referred only to punitive procedures (Kirkup Citation2007).

With the above exceptions, the sources concerning amputations as punishment in Egypt are limited to late accounts from the Roman era (Diodorus Siculus Citation1814, Strabo Citation1854, Jonckheere Citation1954). Diodorus Siculus mentioned the cutting off of tongues, hands, and genital parts. He referred to a now lost depiction in the mortuary temple of Ramses II with captives of war “without hands and privy members” (Diodorus Siculus Citation1814, Jonckheere Citation1954). Based on similar surviving scenes, such as those in the nearby temple of Ramses III () (CitationBreasted 1932), it is evident that these procedures were performed on dead enemies as a way of counting bodies (Aldred Citation1964). This is supported by the associated inscriptions (Breasted Citation1936, Hölscher Citation1937).

Figure 5. Counting of hands and phalluses in Medinet Habu. From CitationBreasted (1932).

Perhaps the most important contribution to the perception of amputations as an Egyptian therapeutic procedure comes from none other than the famous surgeon of Napoleon, Larrey. In his memoires of the Egyptian campaign under Napoleon, he wrote appreciatively about the surgical skills of the ancient Egyptians, and provided the following information from his visit to Thebes:

“On the ceilings and walls of these temples are bas-reliefs, representing limbs, cut off with instruments very similar to those used at present in surgery, for amputating. Instruments of the same kind are described in their hieroglyphicks, and traces are discovered of surgical operations, which prove that their surgery kept pace with the other arts, which appear to have been carried to a high degree of perfection.” (Larrey Citation1812, Citation1814).

Unfortunately, no depictions of amputations are known from Thebes. Like Diodorus Siculus, Larrey simply misinterpreted the depictions and hieroglyphs, taking them at face value. This is perhaps an understandable mistake, considering their appearance. A selection of hieroglyphs is provided in . Larrey’s misinterpretation was later quoted in Samuel Cooper’s influential A dictionary of practical surgery and the idea later spread to other works in the modern literature (Cooper and Reese Citation1832, Finlayson Citation1893).

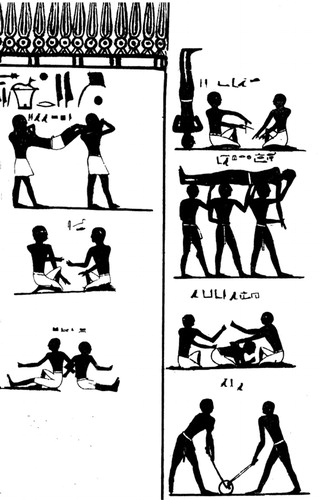

Recently, El Gindi (Citation2002) published another depiction from an “ancient temple”, provided by the famous Egyptologist Zahy Hawas, said to depict an amputation of the upper extremity. The published photo is of poor quality and difficult to interpret. It appears to depict a man holding the ends of a thin thread in each hand, while the thread is curved around another man’s lower arm or arms. A drawing of that scene is provided here in (Newberry et al. Citation1894), but not reversed laterally as in the photo. Considering that the wire saw was introduced in surgery as late as 1894, it does seem safe to discard this suggestion (Gigli Citation1894). Professor Kanawati (personal communication) has further identified the image. It does not stem from an ancient temple but from the tomb of Khety in Beni Hasan and it depicts young boys playing different games, as can be seen from the larger section of the depiction in . Among other games, we can see a boy standing on his head, 2 boys playing with a ring and 2 sticks etc., while the suggested amputation scene in the upper right corner can be more readily interpreted as a game with string.

Figure 7. A sketch of a scene suggested to depict an amputation of the lower arm. Modified from Newberry (Citation1894) (plate XVI).

Figure 8. Some depictions of boys playing games. From the eastern half of the south wall in the tomb of Khety (Tomb 17, Beni Hasan). Modified from Newberry Citation1894 (plate XVI).

The osteological material

Concerning the osteological material, and regarding findings not stemming from well-preserved mummies (the overwhelming majority of cases), we also have to take into account changes that occurred after death. Some bodies would have been buried in an advanced state of decay with parts missing, and some corpses would have been disturbed and divided by plunderers and scavengers. In a disturbed tomb, a fractured femur where the bones of the lower part of the extremity are missing is probably more readily explained by the plundered nature of the tomb than by an amputation. There are frequent examples of restorations of mummies by the embalmers. When the mummy of Ramses IV lost its right hand after mutilation by plunderers, this was replaced with 2 foreign right hands (Smith and Dawson Citation1924). The mummy of Pediamun was made smaller in order to fit into the coffin, which is why his shoulders and arms were detached and discarded and the legs broken at the mid-thigh and the distal parts discarded (Gray Citation1966).

Some findings have, however, indicated lost limbs with signs of healing or other circumstances leading to suggestions of possible therapeutic amputations. The example most often referred to is the case of Brothwell and Møller-Christensen (1963b). They presented the fused remains of an ulna and radius where the distal end had been lost and the stump showed signs of healing with abundant callus, indicating long-term survival. This is an isolated specimen without other parts of the skeleton, but the authors suggested that it was an amputation, possibly of therapeutic nature. However, such a bone bridge is not typical of amputations, but is documented in the Egyptian material following fractures (Smith Citation1910). This find has been compared with other similar cases, indicating that it can be more readily explained as a simple case of nonunion than as a case of amputation (Stewart Citation1974, Sullivan Citation1998).

Dupras et al. (Citation2010) reported 4 cases that they consider to be possible therapeutic amputations from Dayr al-Barsha. 1 case was “a healed amputation of the left ulna near the elbow” where the left radius was missing. Since these bones were found together with the remains of several individuals in a disturbed grave and had to be reconstructed, one should perhaps—as in the case of Brothwell (Citation1963)—consider whether this might simply be a case of nonunion. Another case had apparently succumbed to very severe trauma. The injuries of interest here were in the right upper extremity, where the hand and lower part of the forearm were missing and where superficial cutting marks were found in relation to a fracture of the humerus. Considering the extent of the injuries, it would seem more likely that an attempt was made to cut off the arm in order to free the body from entrapment by a falling block or such like, rather than as a therapeutic amputation. The third case consisted of 2 isolated feet, which were considered to belong to the same individual and which showed a well-healed amputation through all the metatarsophalangeal joints. The fourth case showed a well-healed trans-metatarsal amputation of both feet. These 2 cases call to mind the peace treaty of Ramses II mentioned above. It might also be mentioned that partial foot amputations of prisoners of war are known from the Seneca Indians in historical times (Lawson Citation1709).

Zaki et al. (Citation2010) presented 2 cases from the Old Kingdom of well-healed suggested therapeutic amputations of a forearm and a lower leg. The information on the finds is limited, but it gives the impression that here, with the exception of the suggested amputations, we are dealing with sequestered complete skeletons. Nerlich et al. (Citation2000) reported a case from the third intermediate period in which an amputated big toe was replaced by a wooden prosthesis. The authors considered it unlikely that this would have been a traumatic amputation.

In all of these cases, it is not possible to prove that there was amputation or to disregard the possibility from the osteological material, but only to discuss whether this is a likely explanation.

The oldest known amputation was that of an arm in a Neanderthal. This case has been suggested to be a case of therapeutic amputation, but Majno (Citation1975) has soberly remarked that lions were more common than surgeons in those days. We have to remember that body parts are not only separated by therapeutic amputations, but as mentioned above, also as a punitive measure—and we must also consider war injuries, animals, industrial accidents, etc. Regarding trapped limbs or parts that have almost been separated from the rest of the body, it seems unlikely that the Egyptians would not consider amputation. Examples of amputations in extremis are known not only to be performed by laymen but also by the victims themselves, and they even occur in the animal kingdom. Kirkup (Citation2007) provided a good summary in his excellent work on the history of limb amputation:

“It seems probable that instinctive limb dismemberment took place in prehistoric times, either for dry gangrene, for limb entrapment, or to dispose of crushed and virtually amputated limbs in the presence of open fractures, making use of the fracture site or cutting through joints, especially those of the fingers and toes.” (Kirkup Citation2007).

Considering the simplicity of amputation of fingers and toes, one can well imagine that these might have been removed at times due to gangrene or other causes. There is, however, no direct evidence for therapeutic amputations being part of surgery in ancient Egypt, especially concerning larger limbs. Considering the level of Egyptian surgery in general, this also seems very unlikely. Concerning surgery in general, the procedures described in the medical papyri are of a very simple nature. Furthermore, they appear to have been very uncommon. Not a single surgical incision has been found in any of the tens of thousands of mummies investigated from the Pharaonic period.

In summary, the ancient Egyptians certainly treated fractures of various kinds and with varying degrees of success. Concerning the reductions of dislocated joints and therapeutic amputations, there is no clear evidence of the existence of such procedures. It would, however, be surprising if dislocations were not treated, even though they have not left any traces in the surviving sources. Concerning amputations, the general level of Egyptian surgery makes it unlikely that limb amputations were part of the therapeutic armamentarium, even though they may have been performed under extraordinary circumstances.

I am grateful to Professor Kanawati for his advice and to Professor Hariz for reviewing the language of this manuscript.

The author has no financial interest in ancient Egyptian surgery and has not received any financial support for this work.

- Ackerknecht EH. Primitive surgery. Am Anthropol 1947; 49 (1): 25-45.

- Aldred C. A possible case of amputation. Man 1964; 64: 56.

- Ascaso FJ, Lizana J, Cristobal JA. Cataract surgery in ancient Egypt. J Cataract Refract Surg 2009; 35 (3): 607-8.

- Blomstedt P. Transnasal surgery. J Neurosurg 2012; 117 (2): 381-3.

- Blomstedt P. Dental surgery in ancient Egypt. J Hist Dent 2013; 61 (3): 129-42.

- Blomstedt P. Cataract surgery in ancient Egypt. J Cataract Refract Surg 2014a; 40 (3): 485-9.

- Blomstedt P. Tracheostomy in ancient Egypt. J Laryngol Otol 2014b: In Press.

- Breasted JH. Ancient records of Egypt; historical documents from the earliest times to the Persian conquest. University of Chicago Press, Chicago 1906.

- Breasted JH. The Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus. University of Chicago Press, Chicago 1930.

- Breasted JH. Medinet Habu - Volume II. University of Chicago Press, Chicago 1932.

- Breasted JH. The records of Ramses III - The texts in Medinet Habu volumes I and II. University of Chicago Press, Chicago 1936.

- Brorson S. Management of fractures of the humerus in ancient Egypt, Greece, and Rome: an historical review. Clin Orthop 2009; (467) (7): 1907-14.

- Brothwell D, Moller-Christensen V. Medio-historical aspects of a very early case of mutilation. Dan Med Bull 1963a; 10: 21-5.

- Brothwell DR, Møller-Christensen V. A Possible case of amputation, dated to c. 2000 . Man 1963b; 63: 192-4.

- Capart J. Esquisse d’une histoire du droit pénal égyptien. Rev de l’Uni de Bruxelles 1899-5: 1-38.

- Chung CH. Closed reduction techniques for acute anterior shoulder dislocation: from Egyptians to Australians. Hong Kong Journal of Emergency Medicine 2004; 11 (3): 178 - 88.

- Colton C. Orthopaedic challenges in Ancient Egypt. Bone & Joint 2013; 2 (2): 2-7.

- Cooper S, Reese DM. A dictionary of practical surgery. J. & J. Harper, New York, 1832.

- Davies N. Two Ramesside tombs. Metropolitan museum of art, New York 1927.

- Diodorus Siculus. Historical library, London 1814.

- Dobanovacki D, Milovanovic L, Slavkovic A, Tatic M, Miškovic S, Škoric-Jokic S, Pecanac M. Surgery before Common Era. Arch Oncol 2012; 20 (1-2): 22-35.

- Dupras TL, Williams LJ, De Meyer M, Peeters C, Depraetere D, Vanthuyne B, Willems H. Evidence of amputation as medical treatment in ancient Egypt. Int J Osteoarchaeol 2010; 20: 405-23.

- Ebbell B. The Papyrus Ebers. Levin & Munksgaard, Copenhagen 1937.

- El Gindi S. Neurosurgery in Egypt: past, present, and future-from pyramids to radiosurgery. Neurosurgery 2002; 51 (3): 789-95.

- Filer J. Disease. University of Texas Press, Austin 1996.

- Finlayson J. Ancient Egyptian medicine. BMJ 1893; 1: 748-52, 1014-6, 1160-4.

- Gigli L. Über ein neues Instrument zum Durchtrennen der Knochen, die Drahtsäge. Zbl Chir 1894; 21: 409-11.

- Gray PH. Embalmers’ ‘restorations’. J Egypt Archaeol 1966; 52: 138-40.

- Herodotus. The History of Herodotus. Macmillan and Co., London 1890.

- Hussein MK. Reduction of Dislocated Shoulders as Depicted in the Tomb of Ipuy. BIE 1965-47: 47 52.

- Hölscher W. Libyer und Ägypter: Beiträge zur Ethnologie und Geschichte libyscher Völkerschaften nach den altägyptischen Quellen. J. J. Augustin, Glückstadt 1937.

- Jonckheere F. À la recherche du chirurgien égyptien. Chronique d’Égypte 1951a; 26: 28-45.

- Jonckheere F. La place du prêtre de Sekhmet dans le corps médical de l’ancienne Égypt. In: Actes du VI:e congrès d’histoire des sciences. Amsterdam; 1951b. 324-33.

- Jonckheere F. La “Mesdemet”, cosmétique et médicament égyptiens. Histoire de la médecine 1952; 2 (7): 2-12.

- Jonckheere F. L ’eunuque dans l’Égypte pharaonique. Revue d’hist des sc 1954; 7: 139-55.

- Jäger K. Beiträge zur frühzeitlichen Chirurgie. Kastner, Wiesbaden 1907.

- Jäger K. Beiträge zur prähistorischen Chirurgie (Paläochirurgie). F.C.W. Vogel, Wien 1909.

- Kirkup J. A history of limb amputation. Springer, London 2007.

- Larrey DJ. Mémoires de chirurgie militaire, et campagnes. J. Smith, Paris, 1812.

- Larrey DJ. Memoirs of military surgery. 1st American from the 2d Paris ed. Joseph Cushing, Baltimore, 1814.

- Lawson J. A new voyage to Carolina. s.n., London 1709.

- Majno G. The healing hand. Man and wound in the ancient world. Harvard Unversity Press, Cambridge 1975.

- Mattick A, Wyatt JP. From Hippocrates to the Eskimo—a history of techniques used to reduce anterior dislocation of the shoulder. J R Coll Surg Edinb 2000; 45 (5): 312-6.

- Nerlich AG, Zink A, Szeimies U, Hagedorn HG. Ancient Egyptian prosthesis of the big toe. Lancet 2000; 356 (9248): 2176-9.

- Newberry PE, Griffith FL, Fraser GW. Beni Hasan Part II. Egypt Exploration Fund; Archaeological Survey of Egypt, London 1894.

- Rogers SL. Primitive surgery: skills before science. Thomas, Springfield 1985.

- Said GZ. The management of skeletal injuries in ancient Egypt. AO Dialogue 2002; 15: 12-3.

- Schultz AH. Age changes and variability in gibbons. Am J Phys Anthr 1944; 2: 1-129.

- Smith GE. The most ancient splints. BMJ 1908: 732-4.

- Smith GE. The Archaeological Survey of Nubia—report for 1907-1908. National printing department, Cairo 1910.

- Smith GE, Dawson WR. Egyptian Mummies. George Allen and Unwin, London 1924.

- Stewart TD. Nonunion of fractures in antiquity, with description of five cases from the New World involving the forearm. Bull New York Academy of Medicine 1974; 50: 875-91.

- Strabo. The geography of Strabo. H. G. Bohn, London 1854.

- Sullivan R. Proto-surgery in ancient Egypt. Acta Medica (Hradec Kralove) 1998; 41 (3): 109-20.

- Weinberger BW. The dental art in ancient Egypt. J Am Dent Assoc 1947; 34: 170-84.

- Vikentiev V. Les monuments archaïques. IV-V. Deux rites du jubilé royal à l’époque protodynastique. BIE 1949-32: 171-228.

- von Staden H. Herophilus. The art of medicine in early Alexandria. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1989.

- Zaki ME, El-Din A MS, Soliman M A-T, Mahmoud NH, Basha W AB. Limb amputation in ancient Egyptians from Old Kingdom. J Appl Sciences Res 2010; 6 (8): 913-7.