Abstract

Background — Fast–track has become a well–known concept resulting in improved patient satisfaction and postoperative results. Concerns have been raised about whether increased efficiency could compromise safety, and whether early hospital discharge might result in an increased number of complications. We present 1–year follow–up results after implementing fast–track in a Norwegian university hospital.

Methods — This was a register–based study of 1,069 consecutive fast–track hip and knee arthroplasty patients who were operated on between September 2010 and December 2012. Patients were followed up until 1 year after surgery.

Results — 987 primary and 82 revision hip or knee arthroplasty patients were included. 869 primary and 51 revision hip or knee patients attended 1–year follow–up. Mean patient satisfaction was 9.3 out of a maximum of 10. Mean length of stay was 3.1 days for primary patients. It was 4.2 days in the revision hip patients and 3.9 in the revision knee patients. Revision rates until 1–year follow–up were 2.9% and 3.3% for primary hip and knee patients, and 3.7% and 7.1% for revision hip and knee patients. Function scores and patient–reported outcome scores were improved in all groups.

Interpretation — We found reduced length of stay, a high level of patient satisfaction, and low revision rates, together with improved health–related quality of life and functionality, when we introduced fast–track into an orthopedic department in a Norwegian university hospital.

The health service in Norway has been reorganized in the last decade. The number of available beds and the length of stay (LOS) in somatic hospitals have been reduced. Patients are increasingly being treated as outpatients rather than being admitted to hospital (CitationSSB 2011). Changes in treatment modalities have contributed to this reorganization. Within elective surgery, the “fast–track” principles are increasingly being adopted, although there is still potential for improvement regarding both treatment and clinical results (CitationRostlund and Kehlet 2007, CitationKehlet and Soballe 2010). Fast–track originated in Denmark—in gastrointestinal surgery—and has been further developed and documented in joint replacement surgery in hospitals in Denmark over the last decade (CitationRasmussen et al. 2001, CitationHusted et al. 2010a,Citationd, 2012, CitationLeonhardt et al. 2010). The fast–track concept is an evidence–based multimodality treatment that reduces convalescence time and improves clinical results, including reduction in morbidity and mortality (CitationKehlet and Wilmore 2008, CitationSchneider et al. 2009). The particularly important elements are: anesthesia, fluid therapy, pain therapy, and early postoperative mobilization (CitationHusted and Holm 2006, CitationHusted et al. 2010a, Citation2011a, Citation2012, CitationKhan et al. 2014) as well as preoperative information and supervision (CitationKehlet 1997, CitationAndersen et al. 2007, Citation2009, CitationHolm et al. 2010).

It has been said that fast–track may result in increased complication rates and re–admissions (CitationMauerhan et al. 2003). However, several studies have found that reduced length of stay does not compromise patient safety (CitationPilot et al. 2006, CitationMahomed et al. 2008, CitationSchneider et al. 2009) or increase complication rates compared to conventional treatment methods (CitationHusted et al. 2010b). Also, it has been shown that fast–track surgery with early mobilization and short deep–vein thrombosis prophylaxis results in low rates of deep–vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism (CitationHusted et al. 2010c, CitationJorgensen et al. 2013).

A reorganization in the orthopedic department at Trondheim University Hospital in 2010 led to an increased number of knee and hip arthroplasty patients, from 7 to 17 a week (CitationEgeberg et al. 2010). Based on the successful implementation of fast–track in several hospitals in Denmark (CitationHusted et al. 2008, CitationKehlet and Wilmore 2008), this model was adopted in our department. To be able to continually monitor treatment quality and process data, we established an internal quality register (CitationBjorgen et al. 2012). We now present the 1–year follow–up results after implementation of this fast–track procedure.

Patients and methods

Patients were recruited between September 1, 2010 and December 1, 2012. From September 2010, all elective patients (ASA classification I, II, and stable III) with a diagnosis of arthritis and scheduled for primary total hip replacement surgery (THA) or total knee replacement surgery (TKA) were enrolled in the fast–track system. From May 1, 2012, all elective primary patients (ASA I–IV) and all elective hip and knee revision patients were also enrolled. Acute events such as fractures or 2–stage revisions due to infection were excluded. At discharge, all fast–track patients were scheduled for 2 follow–up consultations with a physiotherapist (knee patients at 2 months and 1 year; hip patients at 3 months and 1 year). Data concerning LOS prior to the fast–track implementation were obtained from the hospital patient administration system.

The fast–track procedure

The fast–track procedure is based on principles previously described (CitationKehlet and Wilmore 2008, CitationHandley 2009, CitationHusted et al. 2010d, CitationKehlet and Soballe 2010, CitationHusted 2012), focusing on standardization and evidence–based care in all parts of the treatment chain. Patients receive oral and written information about the whole procedure, from surgery until follow–up. Patients and relatives are also invited to a multidisciplinary education class arranged at the hospital shortly before admission. An orthopedic surgeon, an anesthetist, a nurse, and a physiotherapist present each part of the treatment chain from admission until discharge. Patients practice walking with crutches and are shown the fast–track unit in which they will be staying during hospitalization. All patients are admitted on the day their surgery is scheduled.

The patients receive optimized pain relief with spinal anesthesia, local infiltration analgesia, and systemic analgesics. The multimodal analgesic regimen is standardized as far as possible; pre–medication consists of paracetamol (1.5–2 g), dexamethasone (16–20 mg), and etoricoxib (90 mg). Benzodiazepines are not used. Operations are done under spinal anesthesia with 2.5–3.0 mL bupivacaine (0.5% plain), preferably at the L2/L3 or alternatively at the L3/L4 vertebral interspace. Propofol infusions are administered for sedation if needed. A standardized program for intraoperative fluid administration is followed consisting of 1–1.5 L Ringer’s acetate, 15 mg/kg transexamic acid (max. 1.5 g), and 2 g cephalothin. Following surgery, patients are transferred to the recovery unit and later to a specialized hip and knee arthroplasty unit with a well–defined and experienced program for multimodal rehabilitation. Multimodal, orally administered opioid–sparing analgesia is given to all patients: etoricoxib (90 mg) and paracetamol (1–1.5 g). Oxycodone (5–10 mg) is given if needed (pain score on the numeric rating scale (NRS) > 4).

All patients are mobilized out of bed in the intensive care unit, as soon as the block from the spinal anesthesia disappears. They are encouraged to be as physically active as possible during the hospital stay, to wear their own clothes, and to have their meals in the dining room in the patient ward. Patients participate in group physiotherapy and are also instructed to individually perform specific joint and muscle exercises several times a day according to an exercise guide. Pain experienced at rest and mobilization is registered on an 11–point NRS with a maximum score of 10 where 0 is no pain and 10 is the worst pain imaginable. Before discharge from hospital, specific criteria must be fulfilled: when mobilized, the pain level must be 3 or less on the NRS, the wound must be dry, and the patient must be able to walk on stairs with crutches. Patients are mainly discharged to their homes and given advice about physiotherapy according to conventional rehabilitation procedures.

Registration

2–12 weeks before surgery, patients are screened by nurses and physiotherapists in the outpatient unit. During hospitalization, data are registered by nurses peroperatively and on a daily basis at the fast–track unit. At the follow–up consultations, the physiotherapist registers follow–up data, provides information about current expectations, and gives advice concerning further rehabilitation. If any adverse results are revealed during these consultations, the physiotherapist refers the patient to a surgeon for consultation.

Pain is registered preoperatively, on a daily basis during hospitalization, and at follow–up. An anonymous patient satisfaction form is filled out by the patient throughout the fast–track course using an 11–point scale (where 0 is worst and 10 is best). LOS is reported as the number of nights hospitalized after the operation. Time to mobilization is defined as the number of hours from the end of surgery to mobilization. Patient–reported outcome scores (PROMS) are measured using (1) the self–administered generic health–related quality of life (HRQoL) questionnaire EQ–5D (CitationRabin and de Charro 2001), a standardized instrument for use as a measure of health outcome, with a score from 0.50 to 1.00, where 1.00 is the maximum score representing perfect health, for both hip and knee patients, (2) the self–administered disease–specific questionnaires Hip Disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score – Physical Function Short Forms (HOOS–PS) for hip patients (CitationDavis et al. 2008), and (3) Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score – Physical Function Short Forms (KOOS–PS) for knee patients (CitationPerruccio et al. 2008). The 2 latter forms have a score from 0 to 100 with 0 being the optimal score, representing no difficulty in performing specific tasks. These are designed for objective assessment of physical function.

All patients are examined by a physiotherapist and physical function is measured by the disease–specific Harris hip score (HHS) and the American Knee Society score (KSS). Maximum score for the HHS is 100 points, with a score of > 70 meaning poor, 70–79 fair, 80–89 good, and 90–100 excellent. The maximum KSS values (knee score and functional score) are 100 points each, with a score of > 60 meaning poor, 60–69 fair, 70–79 good, and 80–100 excellent. All questionnaires are filled out preoperatively and twice postoperatively, knee patients after 8 weeks and hip patients aafter 12 weeks and after 1 year. 1 year after surgery, the patients are asked 2 specific questions: (1) “How does the leg that was operated on work today compared to before surgery?”, and (2) “Based on your experience to date, would you go through the surgery again?”.

Ethics

Before registration, all patients are informed about the registry and asked to sign consent forms allowing their data to be used for scientific purposes. According to our regional ethics committee, the present study was a quality assurance study that did not require any approval in order to be performed or published.

Statistics

The data distribution was evaluated by visual inspection of histograms. Normally distributed data are presented as mean with standard deviation (SD) or range. Since only 13 of the 920 patients (1.4%) had bilateral procedures (bilateral observations), the within–individual correlations were not taken into account in the statistical analyses. Data concerning complications are presented as relative risk with 95% confidence interval (CI) (CitationHagen 1998). The analyses were performed using SPSS version 21.0 and Microsoft Excel.

Results

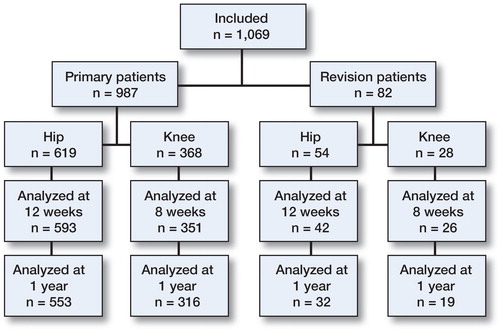

Before the implementation of fast–track, 7 hip or knee arthroplasty patients were operated every week at Trondheim University Hospital and 8 were operated on in a satellite clinic. Mean LOS was 8.1 (5.3) days for primary hip patients and 8.1 (5.1) days for primary knee patients. After fast–track implementation, all hip and knee arthroplasty surgeries were performed at the university hospital, with a total number of 17 surgeries a week. 1,069 fast–track patients were included in the present study: 619 primary THA patients, 368 primary TKA patients, 54 revision THA patients, and 28 revision TKA patients ().

Table 1. Patient characteristics in the different groups (primary total hip arthroplasty and primary total knee arthroplasty; revision total hip arthroplasty and revision total knee arthroplasty)

For THA, the number of 12–week follow–ups was 593 (96%) for primary patients and 42 (78%) for revision patients. For TKA, the number of 8–week follow–ups was 351 (95%) for primary patients and 26 (93%) for revision patients. At the 1–year follow–up, 553 (89%) primary, and 32 (59%) revision hip patients were analyzed, and 316 (86%) primary and 19 (68%) revision knee patients were analyzed. A flow chart of the participants is given in .

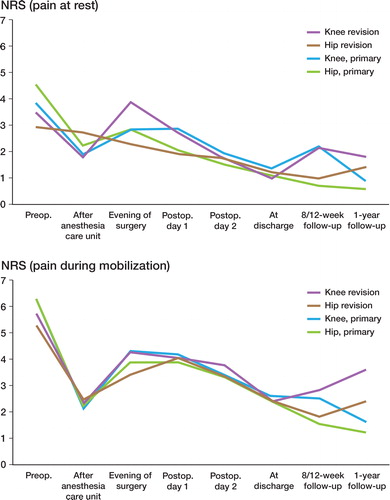

Mean patient satisfaction with the LOS for all patients was 8.9 (1.7), and with the fast–track course it was 9.3 (1.2). Pain scores at rest and during mobilization from before operation until the 1–year follow–up are presented in . PROMS, physical function scores, and complications for primary and revision patients are given in , , and , respectively.

Figure 2. Pain at rest (upper panel) and mobilization (lower panel) at 8 time points, from preoperatively until 1 year postoperatively. Lines represent mean pain score for each patient group.

Table 2. Patient–reported outcome scores (PROMS) in the 4 different groups: EQ–5D, HOOS–PS, KOOS–PS, and the physical function scores HHS and KSS. For abbreviations, see text. All scores were obtained preoperatively, 8 and 12 weeks postoperatively, and 1 year postoperatively. Data are mean (SD)

Table 3. Complications within 1 year of primary total hip arthroplasty or primary total knee arthroplasty

Table 4. Complications within 1 year of revision surgery for hip and knee patients

Primary surgery

Of the THA patients who underwent primary surgery, 94% were mobilized in the recovery unit and the mean time from surgery to mobilization was 3.5 (1.6) h. Mean LOS was 3.1 (0.8) days. 82% of the patients were discharged directly to their homes. Total re–admission rate within one year was 5.7% (4.3–7.0). The revision rate was 2.9% (2.0–3.9), of which 1.6% (0.9–2.3) was caused by infections and 1.0% (0.4–1.5) by dislocations. At 1–year follow–up, 83% reported improved functionality in the operated limb and 85% reported that they would have been willing to have the surgery all over again.

For TKA patients who underwent primary surgery, 96% were mobilized in the recovery unit and the mean time from surgery to mobilization was 3.2 (1.4) h. Mean LOS was 3.1 (0.8) days. 82% of the patients were discharged directly to their homes. Total re–admission rate within 1 year was 10.1% (8.4–11.8). The revision rate was 3.3% (2.3–4.3), of which 1.4% (0.7–2.0) was caused by infections and 1.4% (0.7–2.0) by mechanical causes. At 1–year follow–up, 72% reported improved functionality in the operated limb and 73% reported that they would have been willing to have the surgery all over again.

Revision surgery

For THA patients who underwent revision surgery, 91% were mobilized in the recovery unit and the mean time from surgery to mobilization was 4.6 (2.2) h. Mean LOS was 4.2 (1.6) days and 44% of the patients were discharged directly to their homes. Total re–admission rate within 1 year was 5.6% (4.3–6.9), all of which was caused by infections. At 1–year follow–up, 39% reported improved functionality in the operated limb and 43% reported that they would have been willing to have the surgery all over again.

For TKA patients who underwent revision surgery, 89% were mobilized in the recovery unit and the mean time from surgery to mobilization was 4.9 (1.9) h. Mean LOS was 3.9 (2.2) days and 67% of the patients were discharged directly to their homes. Total re–admission rate within 1 year was 7.1% (5.7–8.6), of which 3.6% (2.5–4.6) was caused by infection and 3.6% (2.5–4.6) was due to mechanical causes. 1 year postoperatively, 48% reported improved functionality in the operated limb and 52% reported that they would have been willing to have the surgery all over again.

Discussion

After implementation of the fast–track course, the number of weekly hip and knee arthroplasty surgeries was increased from 7 to 17. Patient satisfaction was high in all parts of the treatment chain, with a mean score of 9.3 (1.2) out of a maximum of 10. 85% of hip patients and 73% of knee patients were satisfied with the results 1 year after the operation. In addition, LOS was reduced by approximately 5 days for both hip patients and knee patients. The satisfaction with the LOS had a mean score of 8.9 (1.7) out of a maximum of 10. These findings are in line with other publications concerning fast–track arthroplasty (CitationHusted et al. 2008, Citation2010a). Hospital logistics and clinical features are crucial for the LOS, and reduced LOS reduces costs without compromising treatment quality (CitationHusted et al. 2008, Citation2010d, Citation2012). The numbers of re–admissions and revisions in the present study were lower than those previously reported (CitationHusted et al. 2008, Citation2010b). These results demonstrate that even though the treatment is more effective, as indicated by the increased number of patients operated annually and with a reduced LOS, it does not compromise patient satisfaction or treatment quality. Fast–track also provided good results in non–septic revision surgery, as has been reported previously by others (CitationSchneider et al. 2009, CitationHusted et al. 2011b, CitationJorgensen et al. 2013).

Measurement of pain with an NRS is a practical method to use, since it is easy to understand and the patient does not need clear vision or paper and pen to describe the degree of pain—in contrast to the visual analog scale (VAS). An NRS of 3 or less corresponds to “mild pain” on the VAS, whereas 4–6 corresponds to “moderate pain” and 7–10 to “severe pain” (CitationBreivik et al. 2008). Pain, dizziness, and general weakness are main causes of prolonged postoperative hospitalization. Pain is also a limiting factor for early postoperative mobilization and physical activity (CitationHusted et al. 2011a). In general, the patients in our study had only mild pain directly after or during the evening following surgery. We found that the maximum pain experienced was during rest in the evening after surgery, both for primary hip and knee patients and for revision hip and knee patients (2.9 (2.0), 2.9 (2.0), 2.3 (1.8), and 3.9 (2.6), respectively). From day 2 postoperatively to patient discharge, the pain both at rest and during mobilization was reduced and sustained at the “mild pain” level. These results suggest that pain was no limitation regarding early discharge.

For optimal rehabilitation and assured function, patients need continuous analgesic treatment after discharge (CitationAndersen et al. 2009, CitationHusted et al. 2011a). CitationHolm et al. (2010) found that pain has a limited influence on functional recovery after the first postoperative day after TKA, thereby allowing early physiotherapy. They found that 90% of the patients were mobilized after the first postoperative day, which agrees with our findings. We found that over 90% of the primary patients and about 90% of the revision patients were mobilized at the recovery unit, and the mean time from surgery until mobilization was about 3.5 h and 4.5 h, respectively. Patients who were not mobilized were either immobilized due to perioperative complications, illness, or inability to cooperate.

Early mobilization is important to reduce the risk of thrombosis and to initiate rapid recovery (CitationHusted et al. 2008, Citation2010b,Citationc). The numbers of deep–vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism could be underreported in our study. These diagnoses had to be verified by ultrasonography or CT before being reported to the registry.

All the patients had to fulfill the fast–track discharge criteria before leaving hospital, either to their homes or to the rehabilitation institution. Before the fast–track implementation, there were no standardized discharge criteria, and the patients usually went to a rehabilitation institution. Approximately 80% of the primary patients in our study were discharged directly to their homes, which is a lower percentage than can be found in publications from Denmark (CitationHusted et al. 2008). In Norway, it has been a tradition to discharge patients to rehabilitation institutions depending, for example, on the patient’s housing conditions, care facilities, comorbidities, and distance from hospital. Now that fast–track has been implemented, this trend is about to shift. Only 44% of the revision patients were discharged to their homes due to their reduced functionality postoperatively—the result of greater surgical trauma, as full synovectomi and intramedular reaming for femoral and tibial components are used in the revision surgeries. At postoperative follow–ups for all groups at week 8 or 12, and at 1 year, the mean pain score was relatively low, as expected, with values of less than 3 on the NRS. These findings are in line with the results of other studies (CitationRostlund and Kehlet 2007, CitationHolm et al. 2010), demonstrating low levels of postoperative pain after fast–track joint replacement surgery.

Even though the main purpose of THA and TKA surgery is pain relief, regaining HRQoL and functionality is considered to be the ultimate goal after joint replacement (CitationWoolf and Akesson 2001). Thus, to evaluate the treatment outcome, it is important to measure outcomes from the patient’s perspective. In a fast–track treatment set–up without any formal intensive rehabilitation after discharge, it was found that THA and TKA patients at 1–year follow–up had regained health similar to that of an age– and sex–matched population in Denmark when measured by HRQoL (EQ–5D) (CitationLarsen et al. 2010, Citation2012). We found similar improvements (using EQ–5D scores) one year after primary THA and TKA to those reported by Larsen et al. However, the patients in our study did not reach the same HRQoL levels 1 year postoperatively, which may have been due to the different demographics of the patient cohorts. Patients included in the hip study (CitationLarsen et al. 2010) had a diagnosis of unilateral primary arthritis, and in the knee study (CitationLarsen et al. 2012) patients with unicompartmental knee arthroplasty were included. In the present study, patients with bilateral hip arthroplasty were included and patients with unicompartmental knee arthroplasty were excluded. Thus, our patients may have been affected by the disease to a greater extent than the patients in the Larsen study, therefore resulting in both higher preoperative and 1–year HRQoL scores. EQ–5D results from the Swedish Arthroplasty Register showed that THA patients had mean scores of 0.42 preoperatively and 0.78 after 1 year (CitationRolfson et al. 2011), which is similar to what we found. A cohort study from Karolinska University Hospital in Sweden (CitationJansson and Granath 2011) also found similar EQ–5D results in THA patients pre- and 1 year postoperatively (0.49–0.80, and TKA patients pre- and 1 year postoperatively (0.51–0.73).

The THA patients in the study by CitationLarsen et al. (2010) did not regain the same level of health as the age– and sex–matched normal population, which was based on the disease–specific HHS outcome one year postoperatively (88 vs. 94). However, the results were similar to our findings (HHS = 89) 1 year postoperatively. Any HHS score within these values is close to “excellent” (i.e. close to > 90) on the HHS grading scale, which indicates that even though THA patients have good functionality at 1 year postoperatively in disease–specific terms, they do not reach the level of the normal population. In another study (CitationMedalla et al. 2009), the postoperative KSS outcomes, knee score (81) and physical function score (71), were similar to the postoperative scores that we found (75 and 78, respectively). However, patients in the Medalla study gave their postoperative scores 2 years after surgery, as compared to 1 year in the present study. Also, the patients in the Medalla study generally had a higher knee score and a lower physical function score than in our study. This might be explained by the different postoperative testing times, since knee function is directly related to the surgery and physical function is related to the physical fitness of the patient, which is not directly influenced by the surgery. Scores between 70 and 80 correspond to a “good” knee and functionality score on the KSS grading scale. The knee and physical function scores in the present study were both > 75, which is close to “excellent” (> 80), indicating good functionality one year postoperatively.

In a study from Toronto, Canada (CitationDavis et al. 2009), based on 201 THA and 248 TKA patients, the improvements in HOOS–PS (55%) and KOOS–PS (33%) from preoperatively to 6 months after surgery were similar to what we found. This similarity was apparent in HOOS–PS from before surgery to 3 and 12 months after surgery (51% and 62%, respectively), and in KOOS–PS from before surgery to 2 and 12 months after surgery (21% and 35%), where the patients in both studies reported less difficulty in performing daily activities postoperatively. In light of our findings and those previously reported by others, fast–track is a treatment that gives good postoperative results, both in generic and disease–specific terms.

The overall loss of participants at follow–up in our study 1 year postoperatively was 14%, which is less than that reported by others (26%) (CitationLarsen et al. 2012). A higher proportion of revision patients than primary patients were lost to follow–up at 1 year. Local hospitals often refer patients scheduled for revision surgery to the university hospital. The follow–ups are often done at the local hospital, which could explain the higher loss of patients observed in this group. Patients eligible for follow–up had different reasons for not turning up. In some cases the secretary had not scheduled an appointment, some patients had forgotten the appointment, some patients did not want the consultation, and patients with severe complications at the first follow–up were excluded from the second follow–up. However, all patients with complications resulting in revision were followed up, as they were re–admitted to the same university hospital.

In summary, we found improved efficiency, high patient satisfaction, and low revision rates together with improved health–related quality of life and functionality with the fast–track course implemented in a Norwegian university hospital, indicating that fast–track is a favorable and feasible method of treatment for both primary and revision THA and TKA patients.

All the authors contributed to the literature search, study design, data collection, data analysis, and interpretation. All the authors contributed substantially to drafting of the article and they also revised it for important intellectual content.

No competing interests declared.

- Andersen KV , Pfeiffer–Jensen M , Haraldsted V , Soballe K . Reduced hospital stay and narcotic consumption, and improved mobilization with local and intraarticular infiltration after hip arthroplasty: a randomized clinical trial of an intraarticular technique versus epidural infusion in 80 patients. Acta Orthop 2007; 78 (2): 180–6.

- Andersen LO , Gaarn–Larsen L , Kristensen BB , Husted H , Otte KS , Kehlet H . Subacute pain and function after fast–track hip and knee arthroplasty. Anaesthesia 2009; 64 (5): 508–13.

- Bjorgen S , Jessen V , Husby OS , Roset O , Foss OA . Internal quality register for joint prostheses. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 2012; 132 (6): 626–7.

- Breivik H , Borchgrevink PC , Allen SM , Rosseland LA , Romundstad L , Hals EK , et al. Assessment of pain. Br J Anaesth 2008; 101 (1): 17–24.

- Davis AM , Perruccio AV , Canizares M , Tennant A , Hawker GA , Conaghan PG , et al. The development of a short measure of physical function for hip OA HOOS–Physical Function Shortform (HOOS–PS): an OARSI/OMERACT initiative. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2008; 16 (5): 551–9.

- Davis AM , Perruccio AV , Canizares M , Hawker GA , Roos EM , Maillefert JF , et al. Comparative, validity and responsiveness of the HOOS–PS and KOOS–PS to the WOMAC physical function subscale in total joint replacement for osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2009; 17 (7): 843–7.

- Egeberg T , Aamodt A , Lidegran G , Pedersen N . Protesekirurgi ved St Olavs Hospital etter 2010, Kartlegging av behov og kapasitet for hofte– og kneproteser. 2010.

- Hagen PC . Estimering. In: Innføring i sannsynlighetsrening og statistikk. Cappelen Akademiske Forlag as, Oslo. 1998; 177.

- Handley A . Fast track to recovery. Nurs Stand 2009; 24 (9): 18–9.

- Holm B , Kristensen MT , Myhrmann L , Husted H , Andersen LO , Kristensen B , et al. The role of pain for early rehabilitation in fast track total knee arthroplasty. Disabil Rehabil 2010; 32 (4): 300–6.

- Husted H . Fast–track hip and knee arthroplasty: clinical and organizational aspects. Acta Orthop (Suppl 346) 2012; 83: 1–39.

- Husted H , Holm G . Fast track in total hip and knee arthroplasty—experiences from Hvidovre University Hospital. Denmark. Injury (Suppl 5) 2006; 37: S31–5.

- Husted H , Holm G , Jacobsen S . Predictors of length of stay and patient satisfaction after hip and knee replacement surgery: fast–track experience in 712 patients. Acta Orthop 2008; 79 (2): 168–73.

- Husted H , Hansen HC , Holm G , Bach–Dal C , Rud K , Andersen KL , et al. What determines length of stay after total hip and knee arthroplasty? A nationwide study in Denmark. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2010a; 130 (2): 263–8.

- Husted H , Otte KS , Kristensen BB , Orsnes T , Kehlet H . Readmissions after fast–track hip and knee arthroplasty. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2010b; 130 (9): 1185–91.

- Husted H , Otte KS , Kristensen BB , Orsnes T , Wong C , Kehlet H . Low risk of thromboembolic complications after fast–track hip and knee arthroplasty. Acta Orthop 2010c; 81 (5): 599–605.

- Husted H , Solgaard S , Hansen TB , Soballe K , Kehlet H . Care principles at four fast–track arthroplasty departments in Denmark. Dan Med Bull 2010d; 57 (7): A4166.

- Husted H , Lunn TH , Troelsen A , Gaarn–Larsen L , Kristensen BB , Kehlet H . Why still in hospital after fast–track hip and knee arthroplasty? Acta Orthop 2011a; 82 (6): 679–84.

- Husted H , Otte KS , Kristensen BB , Kehlet H . Fast–track revision knee arthroplasty. A feasibility study. Acta Orthop 2011b; 82 (4): 438–40.

- Husted H , Jensen CM , Solgaard S , Kehlet H . Reduced length of stay following hip and knee arthroplasty in Denmark. 2000–2009 : from research to implementation. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2012; 132 (1): 101–4.

- Jansson KA , Granath F . Health–related quality of life (EQ–5D) before and after orthopedic surgery. Acta Orthop 2011; 82 (1): 82–9.

- Jorgensen CC , Kehlet H , Lundbeck Foundation Centre for Fast–track H , Knee Replacement Collaborative G . Role of patient characteristics for fast–track hip and knee arthroplasty. Br J Anaesth 2013; 110 (6): 972–80.

- Kehlet H . Multimodal approach to control postoperative pathophysiology and rehabilitation. Br J Anaesth 1997; 78 (5): 606–17.

- Kehlet H , Soballe K . Fast–track hip and knee replacement––what are the issues? Acta Orthop 2010; 81 (3): 271–2.

- Kehlet H , Wilmore DW . Evidence–based surgical care and the evolution of fast–track surgery. Ann Surg 2008; 248 (2): 189–98.

- Khan SK , Malviya A , Muller SD , Carluke I , Partington PF , Emmerson KP , et al. Reduced short–term complications and mortality following Enhanced Recovery primary hip and knee arthroplasty: results from 6,000 consecutive procedures. Acta Orthop 2014; 85 (1): 26–31.

- Larsen K , Hansen TB , Soballe K , Kehlet H . Patient–reported outcome after fast–track hip arthroplasty: a prospective cohort study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2010; 8: 144.

- Larsen K , Hansen TB , Soballe K , Kehlet H . Patient–reported outcome after fast–track knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2012; 20 (6): 1128–35.

- Leonhardt JS , E.KB, B.DP, S.RR, S.JH, E.S.SB. Generel tilfredshed med joint care. Sygeplejersken 2010; (19): 4.

- Lovdata. Helsepersonelloven. Helsepersonelloven . 2001.

- Mahomed NN , Davis AM , Hawker G , Badley E , Davey JR , Syed KA , et al. Inpatient compared with home–based rehabilitation following primary unilateral total hip or knee replacement: a randomized controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2008; 90 (8): 1673–80.

- Mauerhan DR , Lonergan RP , Mokris JG , Kiebzak GM . Relationship between length of stay and dislocation rate after total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2003; 18 (8): 963–7.

- Medalla GA , Moonot P , Peel T , Kalairajah Y , Field RE . Cost–benefit comparison of the Oxford Knee score and the American Knee Society score in measuring outcome of total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2009; 24 (4): 652–6.

- Perruccio AV , Stefan Lohmander L , Canizares M , Tennant A , Hawker GA , Conaghan PG , et al. The development of a short measure of physical function for knee OA KOOS–Physical Function Shortform (KOOS–PS)—an OARSI/OMERACT initiative. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2008; 16 (5): 542–50.

- Pilot P , Bogie R , Draijer WF , Verburg AD , van Os JJ , Kuipers H . Experience in the first four years of rapid recovery; is it safe? Injury (Suppl 5) 2006; 37: S37–40.

- Rabin R , de Charro F . EQ– 5D: a measure of health status from the EuroQol Group. Ann Med 2001; 33 (5): 337–43.

- Rasmussen S , Kramhøft MU , Sperling KP . Accelereret operationsforløb ved hoftealloplastik. Ugeskr Laeger 2001; (163): 6912–6.

- Rolfson O , Karrholm J , Dahlberg LE , Garellick G . Patient–reported outcomes in the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register: results of a nationwide prospective observational study. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2011; 93 (7): 867–75.

- Rostlund T , Kehlet H . High–dose local infiltration analgesia after hip and knee replacement—what is it, why does it work, and what are the future challenges? Acta Orthop 2007; 78 (2): 159–61.

- Schneider M , Kawahara I , Ballantyne G , McAuley C , Macgregor K , Garvie R , et al. Predictive factors influencing fast track rehabilitation following primary total hip and knee arthroplasty. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2009; 129: 1585-91.

- SSB. Statistisk sentralbyrå; Helse, sosiale forhold og kriminalitet . http://statbank.ssb.no/statistikkbanken/Default_FR.asp?PXSid=0&nvl=true&PLanguage=0&tilside=selectvarval/define.asp&Tabellid=04434

- Woolf AD , Akesson K . Understanding the burden of musculoskeletal conditions. The burden is huge and not reflected in national health priorities. BMJ 2001; 322 (7294): 1079–80.