Abstract

Background — Randomized trials evaluating efficacy of local infiltration analgesia (LIA) have been published but many of these lack standardized analgesics. There is a paucity of reports on the effects of LIA on functional capability and quality of life.

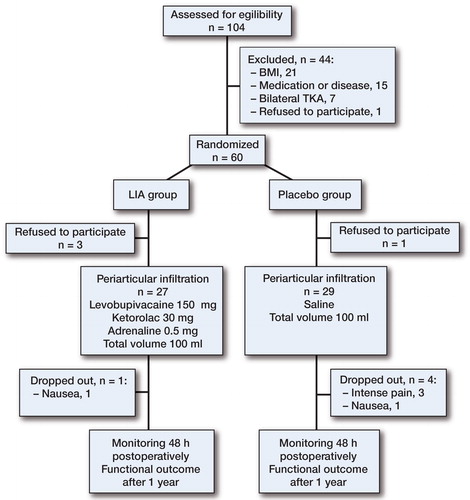

Methods — 56 patients undergoing unilateral total knee arthroplasty (TKA) were randomized into 2 groups in this placebo-controlled study with 12-month follow-up. In the LIA group, a mixture of levobupivacaine (150 mg), ketorolac (30 mg), and adrenaline (0.5 mg) was infiltrated periarticularly. In the placebo group, infiltration contained saline. 4 different patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) were used for evaluation of functional outcome and quality of life.

Results — During the first 48 hours postoperatively, patients in the LIA group used less oxycodone than patients in the placebo group in both cumulative and time-interval follow-up. The effect was most significant during the first 6 postoperative hours. The PROMs were similar between the groups during the 1-year follow-up.

Interpretation — Single periarticular infiltration reduced the amount of oxycodone used and enabled adequate pain management in conjunction with standardized peroral medication without adverse effects. No clinically marked effects on the functional outcome after TKA were detected.

The goal of local infiltration analgesia (LIA) after TKA is to provide simple, effective, and safe pain relief during the first postoperative days, with reduced opiate consumption (Kerr and Kohan Citation2008). Adequate postoperative pain control is usually achieved using multimodal pain management, but it continues to be a challenge in many TKA patients. The recommended intraoperative anesthetic technique during TKA is either general anesthesia combined with femoral nerve block or spinal anesthesia combined with morphine (Fischer et al. Citation2008). Femoral nerve block is effective in reducing pain, but may cause falls after TKA (Ilfeld et al. Citation2010). Opiates, although effective in reducing pain, have severe side effects (nausea, itching, reduced gut mobility, and urinary retention), which may markedly retard the postoperative recovery. Thus, in addition to providing better pain relief, multimodal analgesia is aimed at reducing the amount of opiates used.

Several techniques of infiltration analgesia have been published, with enhanced pain relief for up to 48 hours (Kehlet and Andersen Citation2011). With longer follow-up time, the perioperatively administered LIA loses its efficacy (Essving et al. Citation2010). Furthermore, intra-articular LIA and extra-articular LIA have been reported to be equally effective in reducing postoperative pain (Andersen et al. Citation2008b). The benefit of using an intra-articular catheter has been questioned by some authors—concerning both the effectiveness of pain treatment and the theoretical increased risk of infection (Busch et al. Citation2006, Mullaji et al. Citation2010).

A recently published review divided LIA techniques into 2 groups—single administration and multiple administration—and it also compared different local infiltration techniques (Gibbs et al. Citation2012). Many studies included in that review were poorly controlled, with no standardization of oral analgesics. In the group of multiple administration methods, the reduction of opiate consumption was comparable to the results for the single administration group. Based on these findings, the authors of the review recommended the use of a single, intraoperative and systematic infiltration cocktail of high-dose ropivacaine, adrenaline, and ketorolac to all exposed tissues. Another review highlighted poor documentation of the long-term effect of LIA on knee function and quality of life (Ganapathy et al. Citation2011).

We studied the effects of a single, intraoperative periarticular infiltration on postoperative pain management after TKA.

Patients and methods

We enrolled 60 patients undergoing unilateral TKA in this randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. The inclusion criteria were: (1) need for primary TKA for primary osteoarthritis, and (2) age 18–75 years. Exclusion criteria were (1) rheumatoid arthritis or other inflammatory diseases, (2) BMI > 35, (3) American Society of Anesthesiologists physical score > 3, (4) renal dysfunction, (5) allergy to any of the study drugs, (6) previous high tibial osteotomy or previous osteosynthesis, (7) > 15 degrees varus or valgus malalignment, and (8) physical, emotional, or neurological conditions that could compromise the patient’s compliance to postoperative rehabilitation and follow-up. All patients who were included in the study were operated at our institution between March 2011 and March 2012 ().

Randomization and blinding

In the morning of surgery, an independent research nurse not involved in patient care performed the randomization sequence by drawing 1 opaque, sealed envelope from a collection of 60 alternatives (allocation ratio: 1:1). The nurse prepared the study solution and delivered it to the operation room just before surgery. In the LIA group, the study solution contained levobupivacaine (150 mg) mixed with ketorolac (30 mg) and adrenaline (0.5 mg). In the control (placebo) group, the study solution contained isotonic saline. The total volume of study solution was 100 mL in both groups. The allocation list was stored in the office of the research nurse until all patients had been included and all 1-year follow-up procedures had been completed. Only the research nurse who opened the envelope and prepared the study solution was aware of the type of infiltration, and all other personnel involved in the patient’s care remained blind throughout the study.

Ethics

The study protocol was approved by the local ethics committee (R10108). The Finnish Medicines Agency (Fimea) approved the study protocol regarding the drugs to be used (EudraCT 2010-024315-14). The study was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01305733). All patients gave their informed consent before inclusion in the study.

Preparation and pain management

Oral paracetamol (1 g) was given approximately 1 h before operation as premedication. Single-shot spinal anesthesia was induced at the L4-5 or L3-4 level using a 27-G spinal needle with a dose of 15 mg bupivacaine in 3 mL. A single 3.0-g bolus dose of cefuroxime was used as antibiotic prophylaxis, and tranexamic acid (1 g) was given at the end of surgery. In the post-anesthesia care unit, ice pack was used for all patients. All of them were treated with oral paracetamol (1 g) every 6 h and oral meloxicam (15 mg) every 24 h, starting 2 h after surgery. Patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) with oxycodone (dose: 2 mg; lock-out time: 8 min) was used in all patients to ensure adequate pain relief. No other analgesic drugs were used. If the pain management was insufficient, a lumbar epidural catheter was inserted and levobupivacaine infusion was initiated as rescue analgesic, causing the patient to drop out from the study. Nausea was treated with intravenous ondansetron (4 mg) when needed. As thromboprofylaxis, subcutaneous enoxaparin (40 mg) every 24 h was started 6–10 h after the end of surgery.

Surgery and infiltration technique

All patients were operated with standard knee replacement technique by 4 experienced orthopedic surgeons. Both groups received a periarticular infiltration intraoperatively. All infiltrations were done using 50-mL syringes and 7-cm long 20-G needles. The solution was infiltrated in 2 stages: the first after the bone surfaces were prepared but before the components were inserted, and the second after the components were inserted but before release of both tourniquets and wound closure. The first 50-mL infiltration was aimed from both sides through the posterior capsule and in the areas of resected menisci, and the second was aimed periosteally next to the resected bone surfaces and with parapatellar approach, but not in subcutaneous tissue. The tourniquet was released before closure and before hemostasis was ensured. Drainage and compression bandage were used in all patients.

Recovery

In the recovery room, all patients were mobilized by a physiotherapist soon after recovery of motoric function. Patients were advised to use a PCA pump for oxycodone delivery and the consumption of oxycodone was calculated at 6, 12, 24, and 48 hours postoperatively. The visual analog scale (VAS) was used to quantify the pain intensity, with a target level under 3. VAS reading was recorded by a nurse or physiotherapist 3, 9, 18, and 48 h postoperatively. The range of motion (ROM) was measured by a physiotherapist 6, 12, and 24 h postoperatively.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was oxycodone consumption over 48 h postoperatively. The secondary endpoint was functional outcome 1 year after surgery. All patients were evaluated by a physiotherapist (who was blind regarding the study solution) at a routine follow-up visit 3 months postoperatively. Total knee function questionnaire (TKFQ), Oxford knee score (OKS), high-activity arthroplasty score (HAAS), and the 15D quality-of-life instrument were used preoperatively, at 3 months, and at 1 year after surgery for prospective outcome analysis.

Statistics

Calculation of sample size was based on an expectation of 40% difference in opiate consumption between the groups. The study was designed to have a power of 80% to detect a 40% difference between the 2 groups (type-I error probability: 0.05). Based on power calculation, 17 patients in each group would be needed. Demographics and results are shown as percentage, as mean value (SD), or as median (range). Differences between the groups were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U-test. Bonferroni method was used to correct for multiple measures. IBM SPSS Statistics version 20.0 was used for statistical analysis.

Results

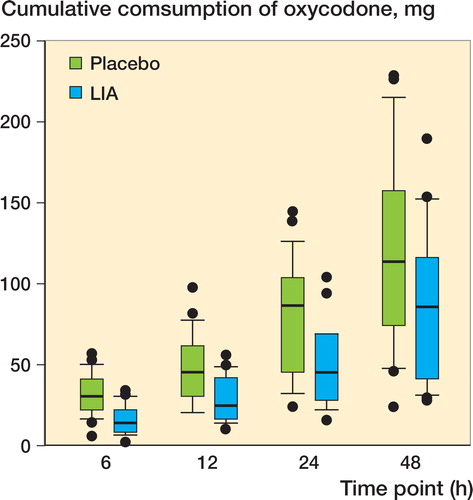

56 patients completed the study—27 patients in the LIA group and 29 patients in the placebo group. Baseline demographics showed similar values in both groups (). The cumulative consumption of oxycodone was smaller in the LIA group to that in the placebo group, at all measured time-points until 48 h (). A trend of reduced consumption of oxycodone in the LIA group persisted up to 24 h postoperatively. The differences in means of cumulative consumption of oxycodone were 17 mg (95% CI: 11–22) at 6 h, 20 mg (CI: 11–30) at 12 h, 28 mg (CI: 11–45) at 24 h, and 35 mg (CI: 5–64) at 48 h.

Table 1. Patient demographic data. Data are mean (SD), number, or median (range)

Figure 2. Median cumulative consumption of oxycodone over 48 h postoperatively. 6 h: p = < 0.001; 12 h: p = < 0.001; 24 h: p = 0.03; 48 h: p = 0.03. The Bonferroni-adjusted p-value for the 48-h time point was 0.1. The line in the middle of the box represents the median. The lower and the upper edges of the box are the 1st and 3rd quartile, respectively. If an observation is beyond 1.5 times interquartile range it is considered as an outlier and marked by a dot. Whiskers are the lowest and highest values that are not outliers.

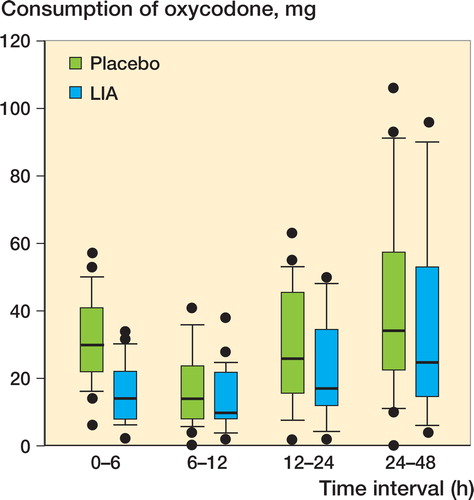

In comparison of the different time intervals, the LIA group used statistically significantly less oxycodone than the placebo group during the first 6 h: mean 14 (2–34) mg as opposed to 30 (6–57) mg (p < 0.001) (). The differences in means according to time intervals were 17 mg (CI: 11–22) at the 0–6 h interval, 4 mg (CI: –1 to 10) at the 6–12 h interval, 7 mg (CI: –2 to 16) at 12–24 h interval, and 5 mg (CI: –11 to 21) at the 24–48 h interval.

Figure 3. Consumption of oxycodone in different time intervals. Consumption is presented as median with 25th and 75th percentiles. 0–6 h: p < 0.001; 6–12 h: p = 0.09; 12–24 h: p = 0.1; 24–48 h: p = 0.4. For the 0–6 h interval, the Boniferroni adjusted p-value was < 0.001.

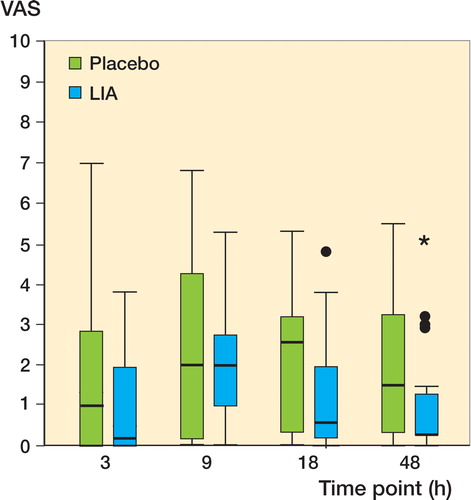

A median level of < 3 in VAS score was considered to be an adequate level of pain management, and this was achieved in both groups until 48 h postoperatively (). The differences in means in VAS were 0.5 (CI: –0.3 to 1.4) at 3 h, 1.0 (CI: –0.2 to 2.1) at 9 h, 0.5 (CI: –0.6 to 1.5) at 18 h, and 0.4 (CI: –0.7 to 1.4) at 48 h.

Figure 4. Postoperative pain at rest. VAS scores are presented as median with 25th and 75th percentiles. 3 h: p = 0.4; 9 h: p = 0.2; 18 h: p = 0.4; 48 h: p = 0.5.

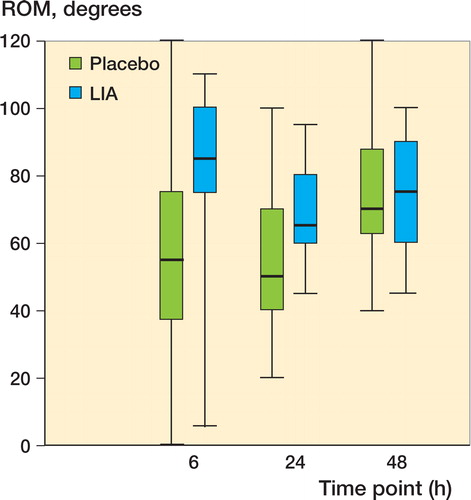

Figure 5. ROM at measured time point. ROMs are presented as median with 25th and 75th percentiles. 6 h: p = 0.001; 24 h: p = 0.08; 48 h: p = 0.6. The Bonferroni-adjusted p-value for the 6-h time point was 0.004.

The difference in mean ROM at 6 hours between the LIA group and the placebo group was –26 (CI: –39 to –12). At 24 h (mean difference –10, CI: –21 to 1) and at 48 h (mean difference –1.5, CI: –13 to 10), the mean differences were not statistically significantly different from that at 0 h.

Postoperatively, 3 patients in the placebo group discontinued the study because of intense pain and they were treated with epidural analgesia. On the other hand, in the LIA group none of the patients discontinued the study because of pain. 1 patient in each group discontinued because of nausea. There was no significant difference in overall blood loss between the LIA group and the placebo group (441 mL vs. 540 mL; p = 0.3). No prosthetic joint infections were detected during the first postoperative year.

The functional outcomes between the groups differed in mean values, but the difference was not statistically significant as measured with HAAS and OKS or as measured with the 15D instrument for quality of life (). However, there was a statistically significant difference between the groups in 1 subscale of the TKFQ questionnaire: at 12 months postoperatively, it was easier for patients in the LIA group to sit for a long period of time (). There was also a trend of higher mean values in OKS for patients in the LIA group 12 months postoperatively ().

Table 2. Functional and quality-of-life results with 1-year follow-up. Results are mean (SD) and mean difference with 95% CI

Discussion

A single intraoperative drug infiltration containing levobupivacaine, ketorolac, and adrenaline reduced the total consumption of oxycodone during the first 48 h postoperatively. The effect of LIA was most pronounced during the first 6 h after surgery. The efficacy of infiltration analgesia was highlighted by the fact that 3 patients in the placebo group discontinued the study because of intensive pain, while none of the patients in LIA group had to do the same. LIA also improved the early knee ROM, but no long-term functional benefit was seen.

In previous studies, the most used local anesthetic drugs have been ropivacaine and racemic bupivacaine. Levobupivacaine is the S-enantiomer of bupivacaine. Compared to ropivacaine, levobupivacaine has a longer duration of action (Burlacu and Buggy Citation2008). Compared to bupivacaine, levobupivacaine appears to have a wider margin of safety in terms of cardiovascular and central nervous system adverse effects when used in large doses (Morrison et al. Citation2000, Burlacu and Buggy. Citation2008). A previous study compared intra-articularly administered bupivacaine and levobupivacaine to placebo and both were found to be more effective than placebo (Bengisun et al. Citation2010). Levobupivacaine has a longer effect time than ropivacaine—which might in theory prolong postoperative analgesia. To maximize the theoretical analgesic effect, we chose the combination of levobupivacaine, ketorolac, and adrenaline. A comparison of 4 different mixtures of LIA (Kelley et al. Citation2013) showed that adding ketorolac to the solution results in better analgesia, and it called into question the significance of other drugs in extending the effect. In the present study, both levobupicaine and ketorolac were administered at maximum dose to ensure maximum effect. The concern with ketorolac—as with all non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)—has been the increased risk of bleeding problems postoperatively. However, in our study the total amount of blood loss was the same in both study groups.

We found that a single periarticular infiltration reduced total consumption of oxycodone for 48 h, although most of this effect was achieved during the first 6 h. Sufficient pain relief immediately after surgery aids in controlling the pain at a later stage also. In a recent review, the benefits of delayed administration were questioned and the authors suggested the use of single intraoperative administration of anesthetic cocktail (Gibbs et al. Citation2012). On the other hand, the use of an intra-articular catheter for additional drug administration may reduce total consumption of opiates up to 48 h postoperatively, compared to the situation where an additional bolus is not given. This is supported by a recent randomized study with 48 h of follow-up and an intra-articular catheter (Essving et al. Citation2010). The total median consumption of opiate in the drug infiltration group was 54 (4–114) mg, as compared to 86 (28–190) mg in our study. Whether or not the additional postoperative, intra-articular bolus is given, supplementary oral medications, e.g. NSAIDs, are needed as an adjunct to infiltration analgesia.

In a randomized study, use of a compression bandage was shown to improve pain control at rest at 8 h, and at 5, 6, and 8 h postoperatively with 90 degrees of knee flexion after TKA (Andersen et al. Citation2008a). We used a compression bandage in all patients (both groups) until the second postoperative day.

There have been few studies analyzing the long-term influence of infiltration analgesia on the functional outcome. The only previous study to evaluate this effect found no difference in functional outcome in the placebo and drug infiltration groups at 3 months postoperatively, as measured with TUG test, OKS, and EQ5D (Essving et al. Citation2010). We found minor differences in functional outcomes as measured with the 15D, HAAS, and OKS instruments, but the clinical relevance of these findings is questionable. The TKFQ scoring system has many subscales for different functional capabilities. The only statistically significant difference was observed at 12 months (sitting for a long period of time), but this was not evident earlier. The statistically significant difference in this TKFQ subscale between groups probably occurred by chance, without any relation to LIA. Murray et al. (Citation2007) concluded that the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) in OKS can be expected to be between 3 and 5 points. In our data, the difference in mean values in OKS between groups at 1 year was 3 points, but the difference was not statistically significant.

We acknowledge that the study had some limitations. Patients were treated according to a routine postoperative rehabilitation protocol, and the length of hospital stay between groups was not measured. Effective postoperative pain relief might have allowed a shorter length of hospital stay. Plasma concentrations of infiltration drugs were not measured, but none of the patients had any side effects identified during the 1-year follow-up period.

In summary, this randomized double-blind study showed that a single perioperative infiltration of levobupivacaine, ketorolac, and adrenaline reduced opiate consumption until 48 h after TKA. The effect was most apparent during the first 6 h, but persisted to some extent up to 24 h. We recommend routine use of perioperative infiltration analgesia as an adjunct to oral pain medication in patients undergoing TKA. However, use of LIA infiltration did not have any effect on the functional outcome of TKA during the first postoperative year.

Design of the protocol: MN, JK, and AE. Enrollment of the patients and surgery: MN, TM, and AE. Anesthetic procedures: JK and AA. Data collection: MN. Data analysis: MN, AE, JK, and AA. All the authors contributed to writing of the manuscript.

We thank Heini Huhtala for statistical advice and research nurse Ella Lehto for assistance with practical issues.

No competing interests declared.

- Andersen LO, Husted H, Otte KS, Kristensen BB, Kehlet H. A compression bandage improves local infiltration analgesia in total knee arthroplasty. Acta Orthop 2008a; 79 (6): 806-11.

- Andersen LO, Kristensen BB, Husted H, Otte KS, Kehlet H. Local anesthetics after total knee arthroplasty: Intraarticular or extraarticular administration? A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Acta Orthop 2008b; 79 (6): 800-5.

- Bengisun ZK, Salviz EA, Darcin K, Suer H, Ates Y. Intraarticular levobupivacaine or bupivacaine administration decreases pain scores and provides a better recovery after total knee arthroplasty. J Anesth 2010; 24 (5): 694-9.

- Burlacu CL, Buggy DJ. Update on local anesthetics: Focus on levobupivacaine. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2008; 4 (2): 381-92.

- Busch CA, Shore BJ, Bhandari R, Ganapathy S, MacDonald SJ, Bourne RB, Rorabeck CH, McCalden RW. Efficacy of periarticular multimodal drug injection in total knee arthroplasty. A randomized trial. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2006; 88 (5): 959-63.

- Essving P, Axelsson K, Kjellberg J, Wallgren O, Gupta A, Lundin A. Reduced morphine consumption and pain intensity with local infiltration analgesia (LIA) following total knee arthroplasty. Acta Orthop 2010; 81 (3): 354-60.

- Fischer HB, Simanski CJ, Sharp C, Bonnet F, Camu F, Neugebauer EA, Rawal N, Joshi GP, Schug SA, Kehlet H, PROSPECT Working Group. A procedure-specific systematic review and consensus recommendations for postoperative analgesia following total knee arthroplasty. Anaesthesia 2008; 63 (10): 1105-23.

- Ganapathy S, Brookes J, Bourne R. Local infiltration analgesia. Anesthesiol Clin 2011; 29 (2): 329-42.

- Gibbs DM, Green TP, Esler CN. The local infiltration of analgesia following total knee replacement: A review of current literature. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2012; 94 (9): 1154-9.

- Ilfeld BM, Duke KB, Donohue MC. The association between lower extremity continuous peripheral nerve blocks and patient falls after knee and hip arthroplasty. Anesth Analg 2010; 111 (6): 1552-4.

- Kehlet H, Andersen LO. Local infiltration analgesia in joint replacement: The evidence and recommendations for clinical practice. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2011; 55 (7): 778-84.

- Kelley TC, Adams MJ, Mulliken BD, Dalury DF. Efficacy of multimodal perioperative analgesia protocol with periarticular medication injection in total knee arthroplasty: A randomized, double-blinded study. J Arthroplasty 2013; 28 (8): 1274-7.

- Kerr DR, Kohan L. Local infiltration analgesia: A technique for the control of acute postoperative pain following knee and hip surgery: A case study of 325 patients. Acta Orthop 2008; 79 (2): 174-83.

- Morrison SG, Dominguez JJ, Frascarolo P, Reiz S. A comparison of the electrocardiographic cardiotoxic effects of racemic bupivacaine, levobupivacaine, and ropivacaine in anesthetized swine. Anesth Analg 2000; 90 (6): 1308-14.

- Mullaji A, Kanna R, Shetty GM, Chavda V, Singh DP. Efficacy of periarticular injection of bupivacaine, fentanyl, and methylprednisolone in total knee arthroplasty:A prospective, randomized trial. J Arthroplasty 2010; 25 (6): 851-7.

- Murray DW, Fitzpatrick R, Rogers K, Pandit H, Beard DJ, Carr AJ, Dawson J. The use of the oxford hip and knee scores. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2007; 89 (8): 1010-4.