Abstract

Background and purpose — Long-term survivors of cancer can develop adverse effects of the treatment. 60% of cancer patients survive for at least 5 years after diagnosis. Pelvic irradiation can cause bone damage in these long-term survivors, with increased risk of fracture and degeneration of the hip.

Patients and methods — Analyses were based on linkage between the Cancer Registry of Norway (CRN) and the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register (NAR). All women who had been exposed to radiation for curative radiotherapy of gynecological cancer (40–60 Gy for at least 28 days) were identified in the CRN. Radiotherapy had been given between 1998 and 2006 and only patients who were irradiated within 6 months of diagnosis were included. The control group contained women with breast cancer who had also undergone radiotherapy, but not to the pelvic area. Fine and Gray competing-risk analysis was used to calculate subhazard-rate ratios (subHRRs) and cumulative incidence functions (CIFs) for the risk of having a prosthesis accounting for differences in mortality.

Results — Of 962 eligible patients with gynecological cancer, 26 (3%) had received a total hip replacement. In the control group without exposure, 253 (3%) of 7,545 patients with breast cancer had undergone total hip replacement. The 8-year CIF for receiving a total hip replacement was 2.7% (95% CI: 2.6–2.8) for gynecological cancer patients and 3.0% (95% CI: 2.95–3.03) for breast cancer patients; subHRR was 0.80 (95% CI: 0.53–1.22; p = 0.3). In both groups, the most common reason for hip replacement was idiopathic osteoarthritis.

Interpretation — We did not find any statistically significantly higher risk of undergoing total hip replacement in patients with gynecological cancer who had had pelvic radiotherapy than in women with breast cancer who had not had pelvic radiotherapy.

After approximately 5 years, two-thirds of cancer patients are still alive (Sant et al. 2009). Research on late adverse effects in cancer survivors has gained increasing interest over the last decade. However, the main interest has been on secondary cancer events (Curtis et al. 2006), cardiovascular complications, and emotional problems (Meyerowitz et al. Citation2008). The relationship between cancer, skeletal disorders, and treatment has rarely been investigated. Skeletal adverse effects of irradiation include cell death, cellular injury, and abnormal bone repair—although the underlying mechanisms are not fully understood (Yurut-Caloglu et al. Citation2010).

Pelvic insufficiency fractures may be one of the possible late side effects of radiotherapy to the pelvic area. The incidence of such fractures has been reported to be 5–20% in gynecological cancer patients who have undergone radiotherapy (Kwon et al. Citation2008, Oh et al. Citation2008, Schmeler et al. Citation2010, Shih et al. Citation2013). Less common effects of pelvic irradiation include acetabular protrusion and avascular necrosis of the femoral head (Fiorino et al. Citation2009). Other studies have not found any increased risk of hip fracture after pelvic irradiation (Feltl et al. Citation2006, Elliott et al. Citation2011). We wanted to examine the risk of receiving a total hip replacement in patients with cancer in the pelvic area who had undergone radiotherapy compared to patients with cancer at another location who had not undergone pelvic irradiation. Our hypothesis was that patients who have had high-dose pelvic radiotherapy would have a higher risk of undergoing total hip replacement than women who have had radiotherapy with target fields in other parts of the body.

Patients and methods

Study population

Since 1953, it has been compulsory to register all new cancer cases in the Cancer Registry of Norway (CRN). The CRN has records on 99% of all cancer patients in Norway (Cancer Registry of Norway Citation2012). This includes information on each cancer episode for each patient regarding type of malignancy, date of diagnosis, initial treatment, and demographics. In 1998, the CRN started a national sub-register containing information about radiation therapy given to cancer patients. For each irradiated patient, this register contains information on target field and dose, fractionation pattern, and start and end of treatments.

The Norwegian Arthroplasty Register (NAR) has been collecting information on total hip arthroplasty in Norway since September 1987. This voluntary register has a compliance rate exceeding 95% (Espehaug et al. Citation2006). For each patient, the NAR has information on each implant operation regarding diagnosis, date of operation, and brand of implant (Norwegian Arthroplasty Register Citation2013).

Data on total hip replacement were linked to the cancer patients using the 11-digit unique personal identification number assigned to each inhabitant of Norway. Cancer patients, all registered total hip replacements, and the date of death for each patient were linked. Then we identified a subgroup consisting of women who had undergone pelvic curative external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) for gynecological cancer and a group without such exposure, represented by female breast cancer patients who had undergone irradiation (40–60 Gy) to the breast area but not to the pelvic area. In the group with pelvic exposure, we identified 568 patients with cervical cancer, 382 patients with endometrial cancer, 10 patients with ovarian cancer, and 2 patients with vaginal and external genital cancer.

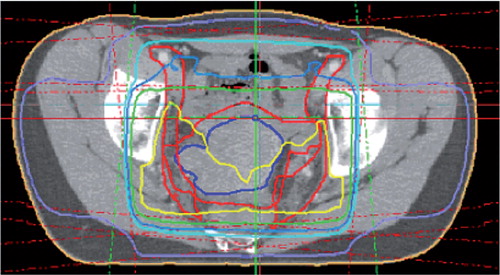

All curative series of pelvic EBRT included in this study were given between 1998 and 2006 (). Only patients who started this radiotherapy within 6 months of diagnosis were included. Furthermore, we restricted the inclusion to patients with target doses of 40–60 Gy to the pelvic area provided over at least 28 days. A radiation dose plan for one patient with cervical cancer is given in . The dose distribution of any brachytherapy was not accounted for. The group without pelvic exposure was defined by a similar linkage between the CRN and NAR, identifying patients who had undergone curative radiotherapy for breast cancer.

Table 1. Patient numbers and numbers of total hip replacements (THRs) by year of therapy

Figure 1. Dose distribution from radiotherapy of a cervical cancer patient. The yellow, light blue, and purple lines represent the 50-Gy, 45-Gy, and 25-Gy isodoses, repectively. The 4 radiation fields applied in patients with cervical cancer encompass the whole pelvis, the distal border of the fields being 0–10 mm below the obturator foramen. Depending on the radiotherapy technique used, the acetabula receive 30–50 Gy while the lateral parts of the hip are irradiated with 10–30 Gy.

Any patients who had undergone total hip replacement prior to radiation therapy were excluded. 8,507 cancer patients (962 with pelvic exposure and 7,545 without pelvic exposure) were included in the study.

Statistics

We used Cox proportional hazards regression models to calculate hazard rate ratios (HRRs) between the pelvic exposure group and the group without pelvic exposure. Because of a substantial difference in mortality between the 2 cancer patient groups, we also calculated sub-hazard rate ratios (subHRRs) using a Fine and Gray regression model, to account for the competing risks between receiving a total hip prosthesis and death (Fine and Gray Citation1999). The sub-hazard is based on the log of the cumulative incidence function (CIF). From the Fine and Gray model, we also present the estimated CIF for receiving a total hip prosthesis.

The observation time was from the patient’s first cancer diagnosis until total hip replacement, death, or the end of the study on December 31, 2010, whichever came first.

We used the statistical software package IBM SPSS Statistics version 21.0 for Windows, and the cmprsk library in the statistical package R, version 3.0.0 (http://www.R-project.org). Any p-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

We identified 962 gynecological cancer patients who had undergone pelvic irradiation therapy (568 cervical cancer, 382 endometrial cancer, 10 ovarian cancer, and 2 vaginal and external genital cancer) and 7,545 breast cancer patients without any pelvic exposure. The mean age at primary diagnosis of gynecological cancer was 58 (SD 14) years, while the corresponding mean age in breast cancer patients was 56 (SD 11) years (). The mean difference in age was 2.4 years (CI: 1.4–3.3; p < 0.001). Gynecological cancer patients had a median follow-up of 7.0 years, while for breast cancer patients median follow-up was 8.1 years.

Table 2. Numbers of cancer patients and of cancer patients who received a total hip replacement (THR), and risk estimates from a Cox model and a Fine and Gray model

26 women with gynecological cancer and 253 women with breast cancer received a primary total hip replacement after the date of primary diagnosis of cancer. The most common reason for undergoing a total hip replacement was idiopathic osteoarthritis, which was observed in 19 gynecological cancer patients (73%) and 192 breast cancer patients (76%). Other reasons for total hip replacement were fracture of the femoral neck in 1 gynecological cancer patient and in 24 breast cancer patients. Hip replacement because of congenital dysplasia was found in 2 gynecological patients and 17 breast cancer patients.

Of the 26 patients with gynecological cancer and total hip replacement, 2 (8%) had since been revised and 5 (19%) had received a primary total hip replacement in the other hip. Of 253 patients with breast cancer and total hip replacement, 6 (2%) had been revised and 42 (17%) had received a primary total hip replacement in the second hip. All patients with total hip replacement were alive at the end of the study (December 31, 2010).

There were 305 deaths in the gynecological cancer patients (32%) and there were 1,052 deaths in the breast cancer patients (14%).

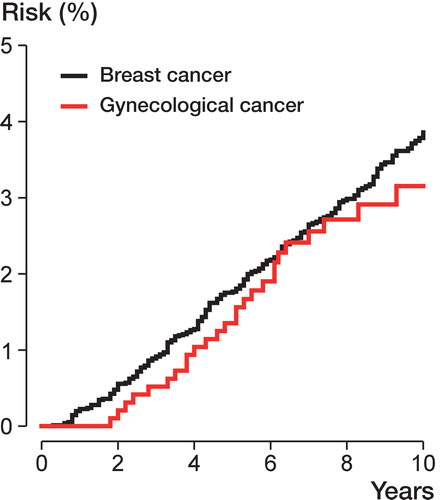

Based on the Fine and Gray method, for gynecological cancer patients the risk (cumulative incidence function) of receiving a prosthesis after 5 years was 1.35% (CI: 1.28–1.43) and after 8 years was 2.72% (CI: 2.61–2.82). The corresponding percentages for patients with breast cancer were 1.77% (CI: 1.74–1.80) and 2.99% (CI: 2.95–3.03) ( and ).

Figure 2. Risk of receiving a total hip replacement, calculated based on cumulative incidence function from the Fine and Gray competing-risk model (with death as the competing risk).

From the Cox proportional hazards regression, with the endpoint total hip replacement and breast cancer patients as reference, we found a hazard rate ratio (HRR) of 0.79 (CI: 0.53–1.20; p = 0.27) for undergoing hip replacement in the gynecological cancer patients (relative to the breast cancer patients). Using the Fine and Gray competing-risk model, adjusting for death as the competing endpoint and with breast cancer patients as the reference category, we found a sub-hazard rate ratio of 0.80 (CI: 0.53–1.22; p = 0.30) for a total hip replacement in gynecological cancer patients ().

Discussion

Radiation therapy directed at the pelvic region may damage bone structures or bone repair in the hip (Fu et al. Citation1994), through an imbalance of—or reduced activity in—osteoclasts and osteoblasts. Based on bone scan images, osteoblast activity within a radiation field is reduced for several years after radiotherapy (Fossa and Winderen Citation1993). Radiation therapy could also cause periarticular fibrosis and increased cartilage degeneration, which might result in a hip replacement (Aigner et al. Citation2002, Hong et al. Citation2010). However, our main hypothesis of increased need of total hip replacement after pelvic radiotherapy was not supported when we compared such patients with a group of cancer patients who had not undergone pelvic radiotherapy.

In an earlier study, we found that cancer patients had a higher risk of receiving a total hip replacement than the Norwegian population as a whole (Dybvik et al. Citation2009). In that study, the type of treatment was not considered. We have found very few studies on hip arthroplasty after radiation therapy (Kim et al. Citation2007, Demircay et al. Citation2009). However, several studies have dealt with fractures in the hip region after pelvic radiotherapy. 1 study showed increased risk of pelvic fractures after pelvic irradiation in older women (Baxter et al. Citation2005), there has been 1 study on groin irradiation (Grigsby et al. Citation1995), and some case reports on pelvic irradiation (Epps et al. Citation2004, Ayorinde and Okolo Citation2009) found femoral neck fracture to be a complication. Other authors have reported femoral head necrosis after irradiation (Hanif et al. Citation1993, Abdulkareem Citation2013).

Our control group of women without pelvic exposure was selected for maximal age-related compatibility with the study group. Since the 1990s, curative treatment of breast cancer patients has not included pelvic radiotherapy, although some of them may subsequently have received low-dose palliative pelvic radiotherapy. Additionally, hormone treatment with Tamoxifen was standard in women with breast cancer in Norway during the timespan of our study. This treatment may prevent osteoporosis (Becker et al. Citation2012), which would reduce the risk of receiving a hip replacement.

1 study found pelvic insufficiency fractures to be uncommon complications in irradiated patients with gynecological cancer (Huh et al. Citation2002), while other studies have found frequent pelvic insufficiency fractures in women after radiation therapy (Abe et al. Citation1992, Blomlie et al. Citation1996, Kwon et al. Citation2008), including acetabulum insufficiency fractures (Ikushima et al. Citation2006, Schmeler et al. Citation2010). None of the patients with gynecological cancer in our study who later received a prosthesis had fracture (or fracture sequelae) registered as the reason for their prosthesis.

The indication for a hip replacement results from a balance between the severity of the hip disease and the general health of the patient. A total hip replacement is a major operation that is generally reserved for healthier patients (Lie et al. Citation2000). If gynecological cancer patients have more severe comorbidity than breast cancer patients, this could lead to bias related to receiving a hip replacement for the 2 cancer types.

Survival in the breast cancer patients and the gynecological cancer patients showed considerable differences. Patient mortality must therefore be taken into account in analysis of the risk of receiving a total hip replacement. This was done using competing-risk analysis according to Fine and Gray (Citation1999), comparing sub hazards. Competing-risk models have become increasingly recognized as an important tool in survival and event history analyses where there can be more than one outcome and the occurrence of the other events may alter the risk of the event of interest. For clinical outcomes such as, for example, a total hip replacement or its revision, death may be a substantial competing outcome that should be taken into consideration in the analysis (Gillam et al. Citation2010, Citation2011). Since mortality in the gynecological cancer patients was much higher than in the breast cancer patients (32% as opposed to 14%), Kaplan-Meier curves might give biased results. Furthermore, since the competing-risk model compares the risks of receiving a hip replacement, it should be favored over the Cox model, even though they did not lead to different conclusions in the present study.

This study had some limitations. A total hip replacement is a clear-cut endpoint, but it may not be ideal since patients whose hips have failed—but who do not receive a hip replacement—will not be included. A hip fracture could be a more sensitive measure of a diseased hip (Gjertsen et al. Citation2008)—or alternatively, patient-reported measures of hip pain (Waldenström et al. Citation2012) or radiographic examination of all patients to disclose joint diseases. The use of breast cancer patients as a comparison group for the gynecological cancer patient group might also be questioned. Ideally, we would like to have compared 2 cancer types with the same etiology, the only difference being the area/location of the irradiation. Using the competing-risk approach, we adjusted for the difference in mortality. However, other etiological factors may contribute to the difference in risk of receiving hip replacement in breast cancer and gynecological cancer patients. Measures of general health and health at the time of receiving THR (e.g. ASA class) and quality of life (e.g. EQ5D) could be factors on the pathway from cancer to the risk of receiving a THR. Such data were not available. Finally, even though this was an observational study based on 2 large national databases, the number of gynecological cancers with curative radiation therapy was limited.

Based on our findings, we conclude that curative pelvic radiotherapy in gynecological cancer patients does not increase the risk of receiving a total hip arthroplasty compared to breast cancer patients who do not undergo pelvic radiotherapy.

All authors participated in the planning and design of the study and in interpretation of the results. Statisticians ED and SAL performed all statistical analyses in collaboration with orthopedic surgeon OF and oncologists SDF and CT. ED was responsible for writing of the draft manuscript, and all the authors participated in critical review and preparation of the final manuscript.

Some of the data in this article are from the Cancer Registry of Norway. The Cancer Registry of Norway is not responsible for the analysis or interpretation of the data presented.

No competing interests declared.

One of the authors (ED) is receiving a PhD grant from the Western Norway Regional Health Authority.

- Abdulkareem IH. Radiation-induced femoral head necrosis. Niger J Clin Pract 2013; 16 (1): 123-6.

- Abe H, Nakamura M, Takahashi S, Maruoka S, Ogawa Y, Sakamoto K. Radiation-induced insufficiency fractures of the pelvis: evaluation with 99mTc-methylene diphosphonate scintigraphy. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1992; 158 (3): 599-602.

- Aigner T, Kurz B, Fukui N, Sandell L. Roles of chondrocytes in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2002; 14 (5): 578-84.

- Ayorinde RO, Okolo CA. Concurrent femoral neck fractures following pelvic irradiation: a case report. J Med Case Rep 2009; 3: 9332.

- Baxter NN, Habermann EB, Tepper JE, Durham SB, Virnig BA. Risk of pelvic fractures in older women following pelvic irradiation. JAMA 2005; 294 (20): 2587-93.

- Becker T, Lipscombe L, Narod S, Simmons C, Anderson GM, Rochon PA. Systematic review of bone health in older women treated with aromatase inhibitors for early-stage breast cancer. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012; 60 (9): 1761-7.

- Blomlie V, Rofstad EK, Talle K, Sundfør K, Winderen M, Lien HH. Incidence of radiation-induced insufficiency fractures of the female pelvis: evaluation with MR imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1996; 167 (5): 1205-10.

- Cancer Registry of Norway, Cancer in Norway 2011 - Cancer incidence, mortality, survival and prevalence in Norway, Oslo, 2012

- Curtis RE, Freedman DM, Ron E, Ries LAG, Hacker DG, Edwards BK, et al. New Malignancies Among Cancer Survivors: SEER Cancer Registries, 1973-2000. National Cancer Institute, NIH Publ. No. 05-5302. Bethesda, MD 2006.

- Demircay E, Unay K, Sener N. Cementless bilateral total hip arthroplasty in a patient with a history of pelvic irradiation for sarcoma botryoides. Med Princ Pract 2009; 18 (5): 411-3.

- Dybvik E, Furnes O, Fosså SD, Trovik C, Lie SA. Long-term risk of receiving a total hip replacement in cancer patients. Cancer Epidemiol 2009; 33 (3-4): 235-41.

- Elliott SP, Jarosek SL, Alanee SR, Konety BR, Dusenbery KE, Virnig BA. Three-dimensional external beam radiotherapy for prostate cancer increases the risk of hip fracture. Cancer 2011; 117 (19): 4557-65.

- Epps HR, Brinker MR, O’Connor DP. Bilateral femoral neck fractures after pelvic irradiation. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 2004; 33 (9): 457-60.

- Espehaug B, Furnes O, Havelin LI, Engesaeter LB, Vollset SE, Kindseth O. Registration completeness in the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop 2006; 77 (1): 49-56.

- Feltl D, Vosmik M, Jirasek M, Stahalova V, Kubes J. Symptomatic osteoradionecrosis of pelvic bones in patients with gynecological malignancies-result of a long-term follow-up. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2006; 16 (2): 478-83.

- Fine JP, Gray RJ. A Proportional Hazards Model for the Subdistribution of a Competing Risk. Journal of the American Statistical Association 1999; 94 (446): 496-509.

- Fiorino C, Valdagni R, Rancati T, Sanguineti G. Dose-volume effects for normal tissues in external radiotherapy: pelvis. Radiother Oncol 2009; 93 (2): 153-67.

- Fossa SD, Winderen M. Does decreased skeletal uptake of 99mTc-methylene bisphosphonate in irradiated bone indicate the absence of bone metastases? Radiother Oncol 1993; 27 (1): 63-5.

- Fu AL, Greven KM, Maruyama Y. Radiation osteitis and insufficiency fractures after pelvic irradiation for gynecologic malignancies. Am J Clin Oncol 1994; 17 (3): 248-54.

- Gillam MH, Ryan P, Graves SE, Miller LN, de Steiger RN, Salter A. Competing risks survival analysis applied to data from the Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry. Acta Orthop 2010; 81 (5): 548-55.

- Gillam MH, Salter A, Ryan P, Graves SE. Different competing risks models applied to data from the Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry. Acta Orthop 2011; 82 (5): 513-20.

- Gjertsen JE, Engesaeter LB, Furnes O, Havelin LI, Steindal K, Vinje T, et al. The Norwegian Hip Fracture Register: experiences after the first 2 years and 15,576 reported operations. Acta Orthop 2008; 79 (5): 583-93.

- Grigsby PW, Roberts HL, Perez CA. Femoral neck fracture following groin irradiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1995; 32 (1): 63-7.

- Hanif I, Mahmoud H, Pui CH. Avascular femoral head necrosis in pediatric cancer patients. Med Pediatr Oncol 1993; 21 (9): 655-60.

- Hong EH, Lee SJ, Kim JS, Lee KH, Um HD, Kim JH, et al. Ionizing radiation induces cellular senescence of articular chondrocytes via negative regulation of SIRT1 by p38 kinase. J Biol Chem 2010; 285 (2): 1283-95.

- Huh SJ, Kim B, Kang MK, Lee JE, Lim DH, Park W, et al. Pelvic insufficiency fracture after pelvic irradiation in uterine cervix cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2002; 86 (3): 264-8.

- Ikushima H, Osaki K, Furutani S, Yamashita K, Kishida Y, Kudoh T, et al. Pelvic bone complications following radiation therapy of gynecologic malignancies: clinical evaluation of radiation-induced pelvic insufficiency fractures. Gynecol Oncol 2006; 103 (3): 1100-4.

- Kim KI, Klein GR, Sleeper J, Dicker AP, Rothman RH, Parvizi J. Uncemented total hip arthroplasty in patients with a history of pelvic irradiation for prostate cancer. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2007; 89 (4): 798-805.

- Kwon JW, Huh SJ, Yoon YC, Choi SH, Jung JY, Oh D, et al. Pelvic bone complications after radiation therapy of uterine cervical cancer: evaluation with MRI. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2008; 191 (4): 987-94.

- Lie SA, Engesaeter LB, Havelin LI, Gjessing HK, Vollset SE. Mortality after total hip replacement: 0-10-year follow-up of 39,543 patients in the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop Scand 2000; 71 (1): 19-27.

- Meyerowitz BE, Kurita K, D’Orazio LM. The psychological and emotional fallout of cancer and its treatment. Cancer J 2008; 14 (6): 410-3.

- Norwegian Arthroplasty Register, http://nrlweb.ihelse.net, 2013.

- Oh D, Huh SJ, Nam H, Park W, Han Y, Lim d H, et al. Pelvic insufficiency fracture after pelvic radiotherapy for cervical cancer: analysis of risk factors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2008; 70 (4): 1183-8.

- Sant M, Allemani C, Santaquilani M, Knijn A, Marchesi F, Capocaccia R. EUROCARE-4. Survival of cancer patients diagnosed in 1995-1999. Results and commentary. Eur J Cancer 2009; 45 (6): 931-91.

- Schmeler KM, Jhingran A, Iyer RB, Sun CC, Eifel PJ, Soliman PT, et al. Pelvic fractures after radiotherapy for cervical cancer: implications for survivors. Cancer 2010; 116 (3): 625-30.

- Shih KK, Folkert MR, Kollmeier MA, Abu-Rustum NR, Sonoda Y, Leitao MM, Jr.et al. Pelvic insufficiency fractures in patients with cervical and endometrial cancer treated with postoperative pelvic radiation. Gynecol Oncol 2013; 128 (3): 540-3.

- Waldenström AC, Olsson C, Wilderäng U, Dunberger G, Lind H, Alevronta E, et al. Relative importance of hip and sacral pain among long-term gynecological cancer survivors treated with pelvic radiotherapy and their relationships to mean absorbed doses. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2012; 84 (2): 428-36.

- Yurut-Caloglu V, Durmus-Altun G, Caloglu M, Usta U, Saynak M, Uzal C, et al. Comparison of protective effects of L-carnitine and amifostine on radiation-induced toxicity to growing bone: histopathology and scintigraphy findings. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2010; 11 (3): 661-7.