Abstract

Background and purpose — It is unclear whether mobile-bearing (MB) total knee arthroplasties reduce the risk of tibial component loosening compared to fixed-bearing (FB) designs. This randomized study investigated implant migration, periprosthetic bone mineral density (BMD), and patient-reported outcomes (Oxford knee score)—all at 2 years—for the P.F.C. Sigma Cruciate Retaining total knee arthroplasty.

Patients and methods — 50 osteoarthritis patients were allocated to either FB or MB tibial articulation.

Resultsand interpretation — At 2 years, the mean total translation (implant migration) was higher for the FB implant (0.30 mm, SD 0.22) than for the MB implant (0.17 mm, SD 0.09) (p = 0.04). BMD decreased between baseline and 1-year follow-up. At 2-year follow-up, BMD was close to the baseline level. The knee scores of both groups improved equally well. The FB tibial implant migrated more than the MB, but this was not clinically significant. The mobile polyethylene presumably partly absorbs the force transmitted to the metal tibial tray, thereby reducing micromotion.

The mobile-bearing (MB) principle was introduced to total knee arthroplasty (TKA) in 1977 due to theoretical advantages such as reduced contact stress, resulting in reduced polyethylene wear and a lower risk of tibial component loosening. In spite of many clinical evaluations, the expected advantages of MB TKA have not been definitively substantiated. Many authors have noted that MB and fixed-bearing (FB) implant designs perform equally well in terms of longevity, loosening, wear, and clinical performance (CitationHansson et al. 2005, CitationHenricson et al. 2006, CitationGupta et al. 2014, Citationvan der Voort et al. 2013). To our knowledge, only 1 prospective randomized study has shown results partly in favor of the MB design (CitationPrice et al. 2003).

In a radiostereometric analysis (RSA) review, CitationRyd (1992) showed early stability to be important for a successful prognosis of implant survival and further noted that the tibial component has at higher risk of aseptic loosening than the femoral component. The magnitude of total migration at 1 year (CitationPijls et al. 2012) and the migration pattern (stability or continuous migration) have been shown to be important—and at different levels of acceptability for cementless and cemented tibial components (CitationRyd et al. 1995, CitationCarlsson et al. 2005).

Owing to the correlation between excessive early implant migration and an increased risk of mechanical failure, migration studies became generally acknowledged as being crucial for promotion of new designs for general use (CitationPijls et al. 2012).

Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) is a validated and suitable method for monitoring of bone remodeling close to implants during the postoperative period (CitationLevitz et al. 1995, Soininvaara et al. 2008, CitationStilling et al. 2010). Reduced proximal tibial bone mineral density (BMD) after TKA has been well documented and could complicate revision surgery (CitationLonner et al. 2001). CitationLi and Nilsson (2001) noticed that decreased periprosthetic BMD and increased tibial component migration do not correlate. They found that BMD reached baseline level after 24 months and that early implant migration was related more to interface issues such as the general condition of trabecular bone than changes in BMD below the implant.

Although decades of clinical research results have been unable to highlight the mobile principle as a winner, it has always been a popular choice among surgeons because of its surgically forgiving design and its improved mobility conditions, which are considered optimal for the patient with an “active lifestyle”. On the other hand, there are possible disadvantages to the mobile bearing design, such as excessive backside wear, PE instability or even—in rare cases—PE spin-out (CitationHuang et al. 2003). In a recent meta-analysis, CitationGupta (2014) discussed whether the shorter time to revision in MB TKA found in their study could be explained by MB articulation creating smaller and biologically more active PE debris particles. In studies with up to 20 years of follow-up, the PE instability of the mobile bearing has been between 0% and 2.2% (CitationHuang et al. 2003, Callaghan et al. 2010). Retrieval studies showed no signs of excessive backside wear (CitationHuang et al. 2003). This could be attributed to a large contact area with lower forces applied per surface unit. For mobile bearings that allow only rotational motion (and not additional anterior/posterior sliding, as with more recent designs), a decoupling of multidirectional motions into monodirectional motion patterns would reduce cross-shear stress and thereby wear.

We performed a randomized trial to compare the MB and FB designs of the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) retaining press-fit condylar TKA. We hypothesized that there would be improved tibial component fixation (by RSA) of a mobile bearing over a fixed-bearing design at 2-year follow-up (with total translation (TT) as primary end point). We also investigated changes in periprosthetic BMD and correlations between implant migration and BMD changes as secondary endpoints.

Patients and methods

Sample size

With a minimal relevant difference of 0.6 mm total translation (power 90%, alpha 0.05, SD 0.6) the study was powered for 22 patients in each group (CitationRyd et al. 1995). We aimed for a total of 50 patients with analyzable baseline stereo radiographs, to compensate for eventual dropouts during follow-up.

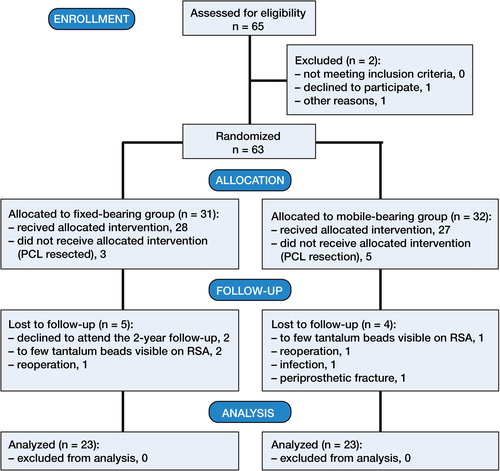

Inclusion and exclusion

From March 2007 to June 2010, 63 patients gave their written consent to participate in the study (at an outpatient visit to the Center for Planned Surgery at Silkeborg Regional Hospital) (). The participants were consecutively included in the study by one senior consultant. Patients who were excluded peroperatively (posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) sacrificed) were replaced with an additional inclusion, to retain the power of the study. The CONSORT flow scheme in provides information on dropouts and missing data. None of the participants had been taking medication to improve their BMD before surgery (i.e. bisphosphonates).

The inclusion criteria were age 50–75 years, uni- or bilateral osteoarthritis (OA), and less than 15 degrees of knee joint extension defect (). The exclusion criteria were any neurological disorder affecting the gait pattern, concomitant orthopedic disease of the ipsilateral hip joint, senile dementia, absence of written consent, and a weakened or missing PCL perioperatively. We also excluded patients who developed (postoperatively) deep infection or abnormal scarring in the knee joint that caused a reduced range of motion.

Table 1. Baseline demographics. Values are mean (range)

Randomization consisted of permuted block randomization with varying block size. The envelopes were drawn just before surgery.

Implants

The tibial implants were all P.F.C. (press-fit condylar) Sigma Cruciate Retaining TKA (DePuy International, Leeds, UK) with fixed- or mobile-bearing tibial designs. The alloy consisted of Co-Cr with a polished surface under the PE. The FB surface facing the bone cement had an average roughness (Ra) of 0.51–1.39 µm and a 20-grit-blast dry aluminium oxide finish. The MB surface facing the bone cement had an Ra of < 1µm and a 220-grit-blast dry aluminium oxide finish (Ra and finish values according to the manufacturer’s information). There was no difference in design regarding the femoral components. All surgical procedures included bone pressure lavage followed by patellar resurfacing and surface cementation (Simplex bone cement; Stryker) of the femoral, tibial, and patellar components using a pressurizing technique.

The operations were performed by 3 senior surgeons. The procedure, with tourniquet, included a midline incision with a para-patellar approach to the knee joint in all patients. The anterior cruciate ligament was excised and the PCL was retained.

The proximal tibia was resected in an attempt to have an implant bearing surface that was perpendicular to the tibial shaft in the coronal plane, but had a 3° posterior slope in the sagittal plane. The distal femoral condyles were resected to attempt an alignment of 6° valgus in the coronal plane. The standard guide system from DePuy was used. For radiostereometric analysis, a minimum of six 1-mm tantalum beads were randomly inserted into the bone surrounding the tibial implant.

All patients followed the same standardized postoperative rehabilitation program allowing full weight bearing immediately after surgery. At discharge, the patients were instructed in a home training program. All patients were seen at an outpatient visit 4 months after their operation.

Implant migration by RSA

Stereoradiographs were obtained 2–7 days after surgery, and they served as the baseline stereo radiographs for the follow-up visits at 3, 6, 12, and 24 months. The patients were placed in supine position with the operated knee parallel to the calibration box, so that the anatomical axis of the leg was parallel with the y-axis of the calibration box. We used a standard RSA setup with 2 synchronized ceiling-fixed roentgen tubes (Arco-Ceil/Medira; Santax Medico, Aarhus, Denmark) and an unfocussed uniplanar carbon calibration box (Medis Specials, Leiden, the Netherlands). All stereo radiographs were CR digital (1,760 × 2,140 pixels). The upper limit for mean-error rigid-body fitting (stable markers used for migration analysis) was 0.5 mm. The mean condition number (dispersion of the bone markers in the tibia) was 17.3 (range 9.7–30.1, SD 4.6).

Analysis of stereo radiographs was performed by one observer (RM) with model-based RSA (MB-RSA) version 3.31 (Medis Specials). The observer used 3D implant computer-aided design (CAD) models that were provided by the implant manufacturer and were subsequently implemented in the MB-RSA software. Implant migration was calculated using the 4 follow-up radiographs with the postoperative radiograph as the reference. The point of measurement was the center of gravity of the CAD model in relation to the tibial bone markers as the fixed rigid-body reference.

Implant translations (implant motion along the axes) were expressed as x-translation (medial and lateral), y-translation (proximal and distal), z-translation (anterior and posterior), and maximum total point motion (MTPM) (CitationRyd et al. 1995, CitationValstar et al. 2005). Rotations (implant movement around the axes) were expressed as x-rotation (anterior and posterior tilt), y-rotation (internal and external rotation), and z-rotation (varus and valgus tilt). Total translation (TT) and total rotation (TR) were calculated using the 3D Pythagorean theorem (TT = √(x2 + y2 + z2). MTPM was given by the MB-RSA software as the unspecified point moving the farthest among the 5,000 points from which the CAD models of the implant were constructed.

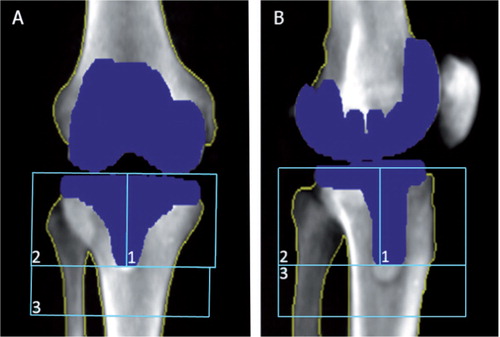

Bone mineral density measured by DXA ()

Figure 2. DXA scans showing implant detection, bone borders, and regions of interest (ROIs). A. Anterior/posterior view. B. Lateral view.

BMD was determined 3 days (range 2–7) postoperatively and at 12- and 24-month follow-up. All scans were performed using a GE Lunar Prodigy Advance 2005 DXA scanner. The observers used enCORE version 11.40.004 “knee” software. This knee software is investigational and has not yet been approved by the FDA. This software has already been shown to be an effective tool in research on periprosthetic bone loss, and the scan method for this study was equivalent (CitationTjornild et al. 2011).

Precision of RSA and DXA

The repeatability of the migration measurements was computed based on double RSA examinations at 12-month follow-up in 49 of the 50 patients who participated. The postoperative stereo radiographs served as the reference in the migration analysis of the double examinations, and the difference was calculated. Ideally, the difference in migration between the double examination migration results should be 0, and if not, it represents the bias (systematic error) of the method. Along the 3 migration axes, the bias for the FB group was x: 0.09 mm; y: 0.06 mm; and z; 0.25 mm. For the MB group, it was x: 0.06 mm; y: 0.07 mm; and z: 0.13 mm. The migration measurement precision (random error = 1.96 × SD) along the 3 migration axes for the FB group was x: 0.23 mm; y: 0.15 mm; and z: 0.64 mm. For the MB group, it was x: 0.11 mm; y: 0.10 mm; and z: 0.25 mm. The measurement precision of the TT and the MTPM measurements in the 2 articulation groups was 0.40 mm and 1.20 mm, respectively, for the FB group and 0.24 mm and 0.61 mm, respectively, for the MB group. The repeatability of the BMD measurements was as recently published (CitationTjornild et al. 2011).

Knee score

The patients themselves filled out the Oxford knee score before surgery and at 6-, 12-, and 24-month follow-up. The Oxford knee score consists of 12 questions on how the patients experience their pain, function, and performance. A maximum of 48 points can be obtained.

Statistics

We compared the FB and MB groups regarding migration, change in BMD, and knee score by using the 2-sample t-test with equal variances (RSA) and the non-parametric Wilcoxon’s rank sum test when the data were abnormally distributed (DXA and Oxford knee score). Normal distribution was tested with the Shapiro-Wilk test. The primary endpoints were the total translation and total rotation values.

The correlation between implant migration and change in BMD was investigated with Spearman’s rho test. Statistical significance was assumed at p < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed with Stata/SE software version 11.1.

Ethics

The study was approved by the Central Denmark Region Committees on Biomedical Research Ethics (registration number: 20050031; date of issue: June 24, 2005). All investigations were conducted in accordance with ethical principles of research (the Helsinki Declaration II) and informed consent was obtained from all the participants. The study was registered with the Danish Data Protection Agency and at www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01150929). The study has been reported in accordance with the CONSORT guidelines for trials and the recent RSA guidelines (CitationValstar et al. 2005).

Results

RSA

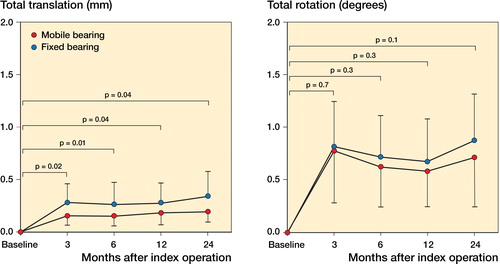

The implants mainly migrated between baseline and the 3-month follow-up (). Total translational migration (TT) (in mm) was statistically significantly higher in the FB group at all 4 follow-up times. On the other hand, the total rotational migration (TR) (in degrees) was similar between groups at all 4 follow-up times and all components seemed well fixed throughout the follow-up period ( and ). There was no trend of any one-directional migration pattern; we found an even distribution between positive and negative migration values in both implant groups.

Table 2. Migration results at 24 months

Between the 12- and 24-month follow-up, 2 knees in each group migrated more than 0.2 mm. These patients had no outlying pattern regarding BMD change and had high Oxford knee scores.

The MTPM was not significantly different between implant groups at all follow-up times. At the 24-month follow-up, the mean MTPM value was 0.69 mm (SD 0.37) for FB and it was 0.55 mm (SD 0.28) for MB (p = 0.1).

DXA

Bone loss was similar in the FB group and the MB group at the 12-month follow-up and at the 24-month follow-up ().

Table 3. Percentage BMD change between baseline, 12-month follow-up, and 24-month follow-up

Correlation between migration and bone loss

Spearman’s rho did not show any correlation between the total translation and the change in BMD for either the MB group or the FB group at the 24-month follow-up.

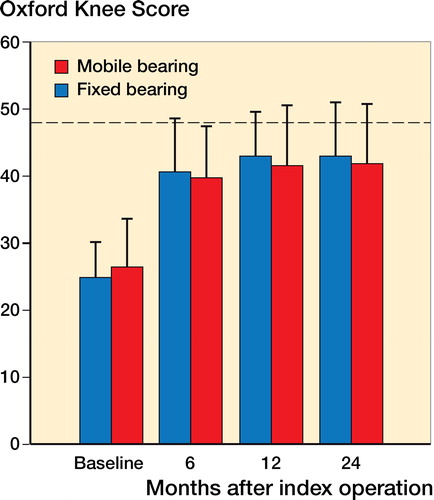

Oxford knee score—clinical performance

Both implant groups improved significantly in Oxford knee score between baseline and 6-month follow-up. There was no statistically significant difference between the FB group and the MB group at the 6-, 12-, or 24-month follow-up times ().

Discussion

We found higher migration of tibial implants with the fixed-bearing PE than in tibial implants with the mobile-bearing PE. In comparison to other publications, however, the degree of migration for both the fixed-bearing and the mobile-bearing articulation was relatively small.

CitationRyd et al. (1995) used RSA as a predictor of mechanical knee implant loosening of uncemented tibial implants, and found migration of 2.7 mm (MTPM) in revised implants and 1.0 mm (MTPM) in stable implants at the 1-year follow-up. Migrations of more than 2 mm between 12 and 24 months were considered to be “continuous migration” with increased risk of aseptic loosening. In the present study, 2 patients in each group had migration of more than 2 mm between the 12-month and the 24-month follow-up.

CitationHansson et al. (2005) reported no difference in implant migration (using marker-based RSA) at 2-year follow-up when they compared an uncemented mobile-bearing tibial component with a fixed-bearing tibial component. They found an MTPM of between 1.4 mm and 1.7 mm at 12 months, whereas the cemented P.F.C. Sigma implants in our study had migrated markedly less at 12 months—in both the fixed-bearing group and the mobile-bearing group. Using a model-based RSA evaluation method, the MTPM is a virtual value based on the 1 point out of 5,000 points in total that migrates most. This is because the computer-aided design model of the implant is described by 5,000 points (triangles). For marker-based RSA, all points in the implant migration are known (normally 3–5 tantalum beads attached to the implant), so the MTPM gives 3D vectored direction information, but without a direction representing the magnitude of the migration (CitationRyd et al. 1995). Even so, for didactic and comparison-enhancing purposes, we included the MTPM values in the present study.

In a marker-based RSA study, CitationHenricson et al. (2006) compared a cemented fixed-bearing TKA to a mobile-bearing TKA, but they found no similar migration at either 12 or 24 months of follow-up. At 12-month follow-up, they measured an MTPM of between 0.39 mm and 0.51 mm and at 24 months, they measured an MTPM of between 0.56 mm and 0.57 mm. As with the fixation principle (cemented) and the stemmed component design, these migration measurements are similar to those in the present study. Other earlier publications support the finding that cemented implants migrate less than uncemented ones (CitationRyd et al. 1995, CitationCarlsson et al. 2005). A recent Cochrane review concluded that cemented implants migrate less than uncemented ones, but cemented implants showed a higher risk of aseptic loosening (at 2-year follow-up) due to a continuous migration pattern (CitationNakama et al. 2012). To our knowledge, only 1 publication has shown a cemented tibial component to stabilize without continuous migration after 5 years (CitationHenricson et al. 2013). The migration pattern—rather than the magnitude of migration—appears to be important for implant longevity. We found 2 patients in each group who had migration of more than the ninetieth percentile (TT). Of these 4 patients, only 3 showed MTPM of more than 1 mm. None of these 4 patients had a low Oxford knee score, and their change in BMD showed no outlying pattern. The patients with high migration had even more improved knee scores than the total group of patients; thus, the relatively limited migration shown in this study does indicate symptomatically loose implants. Throughout the follow-up period, we found that the TT in the FB group was higher than the TT in the MB group. The reason for this difference in migration could be attributed to the difference in the bearing principle. The TR and MTPM were higher in the FB group at the 2-year follow-up, but not statistically significantly so. Type-2 error might explain this statistical insignificance.

The MB principle has been credited with the ability to translate the multidirectional motions of a knee joint into monodirectional motion patterns. This ability should, in principle, reduce cross-shear stress and ultimately reduce wear, but it might also be responsible for the reduction in migration shown in this study. CitationGarling et al. (2005) reported a comparably low variability in migration with a mobile bearing. Obviously, the differences in stem design and surface characteristics might also explain our findings. Whether or not the slightly more structured surface (towards the cement mantle) of the MB stem could account for the lower migration cannot be determined in this study. This difference in surface, however, is placed in the cement/implant interface, which should be recognized as one entity after cementation.

We found that the BMD decreased from baseline to the 12-month follow-up, which is in accordance with other publications (CitationMinoda et al. 2010). Some authors have reported that BMD returned to baseline level within 24 months postoperatively (CitationLi and Nilsson 2001, Soininvaara et al. 2008), but other authors have reported continuous bone loss after TKA in longer follow-up studies (CitationLevitz et al. 1995). In the present study, the BMD at 24-month follow-up almost normalized to the baseline level.

The use of DXA as a follow-up method has been criticized for its inaccurcies, and in contrast to the reproducible setup of RSA, DXA follow-up scans could be influenced by changes in knee flexion or rotation that cause false estimates of BMD changes (CitationStilling et al. 2010, CitationTjornild et al. 2011). The precision measurements for DXA in this study showed a higher coefficient of variation (CV) for the lateral-image (LA) scans than for the AP scans; however, the CV-precision in this study is comparable to other reports (CitationStilling et al. 2010, CitationTjornild et al. 2011). Another possible source of inaccuracy in BMD analysis of the proximal tibia is the outline and presence of the fibula in the scans. Our study included the fibula and the cortical bone, since total fibular extraction would be impossible due to fibular over-projection onto the tibia. Most TKA studies with BMD measurements have used different placements and sizes of regions of interest (ROIs), which makes comparison of results between studies difficult (CitationLi and Nilsson. 2000, CitationStilling et al. 2010). A consensus on ROI placement in TKA studies similar to the use of Gruen zones with hip arthroplasties would enhance the comparability of knee studies. Finally, the 2 tibial tray designs have lateral flanges connecting the tibial plateau and the stem. When the leg is rotated, these flanges cover various parts of the bone in the ROI, and for the MB tibial tray this coverage could be more interfering, since the MB lateral flanges are a little wider than the FB flanges (CitationTjornild et al. 2011).

The association between the decrease in BMD and the increase in migration of TKA as well as THA has been reported with different conclusions (CitationPetersen et al. 1999, CitationLi and Nilsson 2001). We found no correlation between the migration (total translation) and changes in BMD after the 24-month follow-up. CitationLi and Nilsson (2001) found no difference in migration using either cemented or uncemented tibial implants after 2 years of follow-up. In their study, most implant migration was observed during the first 3 months—as was the case in our study. CitationMinoda et al. (2010) found no difference in BMD change between FB and MB tibial implants at 2-year follow-up. CitationPetersen et al. (1999) found less migration in tibial components with high preoperative BMD. No postoperative changes in BMD were described in their study, so their conclusion was that good bone quality improves implant fixation.

MB PE may lose mobility over time. This could be a possible explanation for the comparable change in BMD in the 2 implant groups.

The differences in size and patterns of BMD change—however statistically insignificant—in the postoperative period could mainly be an effect of periprosthetic stress distributed differently by various implant designs (CitationLonner et al. 2001) and possible differences in bone necrosis after bone saw-cutting, pulse-lavage, and also toxic and thermal trauma after cementation (CitationLi and Nilsson. 2001).

In 8 patients, we could not retain the PCL, as it prevented full extension. These 8 patients were therefore excluded from the study. PCL removal (posterior release) is one among many strategies to obtain full knee joint extension peroperatively. An alternative to PCL removal is to remove more femoral bone, but this procedure will position the knee joint line higher, with risk of future problems with the muscle apparatus around the knee joint. The discussion of whether to remove or retain the PCL was reviewed by CitationVerra et al. (2013), who found no clear evidence in favor of either of the 2 methods.

In conclusion, we found higher migration for the P.F.C. Sigma fixed-bearing tibial plateau than for the mobile-bearing tibial plateau, with equal loss of periprosthetic BMD at the two-year follow-up time. Overall, the implant migration measured was low and similar to that reported for other well-performing cemented TKAs. We found no clinically relevant migration after 3 months, but only an extended follow-up period will reveal whether these cemented implants actually have stabilized as shown by CitationHenricson et al. (2013) Both implant groups showed high patient satisfaction, which is also in accordance with the literature (CitationHanusch et al. 2010). Thus, the decision between fixed bearing and mobile bearing is still open for discussion and further research. From our results, both implants can be used according to the surgeon’s choice, and good long-term fixation is to be expected with both implants. The Danish Knee Arthroplasty Registry (2013) reported a 10-year survival rate of 95% for both implants (www.dkar.dk).

We plan a longer follow-up period with an extended investigational program (RSA, DXA, and patient-related outcome measures).

MT, MS, KS, and CH jointly formulated the research hypothesis. PMH and CH performed surgery. MT and MS performed the analyses. MT wrote the draft manuscript and all the authors participated in revising the paper.

We thank senior consultants emeritus Erik Horlyck and Herluf Kristensen for their participation in the planning of the study. We are also grateful to the research laboratory personnel of Silkeborg Regional Hospital and Aarhus University Hospital for their valuable help in follow-up coordination and RSA analysis.

DePuy International supported the study financially. DePuy International had no influence on data collection or analysis, nor on the preparation of the manuscript.

- Carlsson A, Bjorkman A, Besjakov J, Onsten I. Cemented tibial component fixation performs better than cementless fixation: A randomized radiostereometric study comparing porous-coated, hydroxyapatite-coated and cemented tibial components over 5 years. Acta Orthop 2005; 76 (3): 362-9.

- Garling EH, Valstar ER, Nelissen RG. Comparison of micromotion in mobile bearing and posterior stabilized total knee prostheses: A randomized RSA study of 40 knees followed for 2 years. Acta Orthop 2005; 76 (3): 353-61.

- Gupta RR, Bloom KJ, Caravella JW, Shishani YF, Klika AK, Barsoum WK. Role of primary bearing type in revision total knee arthroplasty. J Knee Surg 2014; 27(1): 59-66.

- Hansson U, Toksvig-Larsen S, Jorn LP, Ryd L. Mobile vs. fixed meniscal bearing in total knee replacement: A randomised radiostereometric study. Knee 2005; 12 (6): 414-8.

- Hanusch B, Lou TN, Warriner G, Hui A, Gregg P. Functional outcome of PFC sigma fixed and rotating-platform total knee arthroplasty. A prospective randomised controlled trial. Int Orthop 2010; 34 (3): 349-54.

- Henricson A, Dalen T, Nilsson KG. Mobile bearings do not improve fixation in cemented total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2006; 448: 114-21.

- Henricson A, Rosmark D, Nilsson KG. Trabecular metal tibia still stable at 5 years: An RSA study of 36 patients aged less than 60 years. Acta Orthop 2013; 84 (4): 398-405.

- Huang CH, Ma HM, Lee YM, Ho FY. Long-term results of low contact stress mobile-bearing total knee replacements. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2003; (416) (416): 265-70.

- Levitz CL, Lotke PA, Karp JS. Long-term changes in bone mineral density following total knee replacement. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1995; (321) (321): 68-72.

- Li MG, Nilsson KG. Changes in bone mineral density at the proximal tibia after total knee arthroplasty: A 2-year follow-up of 28 knees using dual energy X-ray absorptiometry. J Orthop Res 2000; 18 (1): 40-7.

- Li MG, Nilsson KG. No relationship between postoperative changes in bone density at the proximal tibia and the migration of the tibial component 2 years after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2001; 16 (7): 893-900.

- Lonner JH, Klotz M, Levitz C, Lotke PA. Changes in bone density after cemented total knee arthroplasty: Influence of stem design. J Arthroplasty 2001; 16 (1): 107-11.

- Minoda Y, Kobayashi A, Iwaki H, Ikebuchi M, Inori F, Takaoka K. Comparison of bone mineral density between porous tantalum and cemented tibial total knee arthroplasty components. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2010; 92 (3): 700-6.

- Nakama GY, Peccin MS, Almeida GJ, Lira Neto Ode A, Queiroz AA, Navarro RD. Cemented, cementless or hybrid fixation options in total knee arthroplasty for osteoarthritis and other non-traumatic diseases. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012; 10: CD006193.

- Petersen MM, Nielsen PT, Lebech A, Toksvig-Larsen S, Lund B. Preoperative bone mineral density of the proximal tibia and migration of the tibial component after uncemented total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 1999; 14 (1): 77-81.

- Pijls BG, Valstar ER, Nouta KA, Plevier JW, Fiocco M, Middeldorp S, Nelissen RG. Early migration of tibial components is associated with late revision: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 21,000 knee arthroplasties. Acta Orthop 2012; 83 (6): 614-24.

- Price AJ, Rees JL, Beard D, Juszczak E, Carter S, White S, de Steiger R, Dodd CA, Gibbons M, McLardy-Smith P, Goodfellow JW, Murray DW. A mobile-bearing total knee prosthesis compared with a fixed-bearing prosthesis. A multicentre single-blind randomised controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2003; 86 (1): 62-7.

- Ryd L. Roentgen stereophotogrammetric analysis of prosthetic fixation in the hip and knee joint. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1992; (276) (276): 56-65.

- Ryd L, Albrektsson BE, Carlsson L, Dansgard F, Herberts P, Lindstrand A, Regner L, Toksvig-Larsen S. Roentgen stereophotogrammetric analysis as a predictor of mechanical loosening of knee prostheses. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1995; 77 (3): 377-83.

- Stilling M, Soballe K, Larsen K, Andersen NT, Rahbek O. Knee flexion influences periprosthetic BMD measurement in the tibia. suggestions for a reproducible clinical scan protocol. Acta Orthop 2010; 81 (4): 463-70.

- Tjornild M, Soballe K, Bender T, Stilling M. Reproducibility of BMD measurements in the prosthetic knee comparing knee-specific software to traditional DXA software: A clinical validation. J Clin Densitom 2011; 14 (2): 138-48.

- Valstar ER, Gill R, Ryd L, Flivik G, Borlin N, Karrholm J. Guidelines for standardization of radiostereometry (RSA) of implants. Acta Orthop 2005; 76 (4): 563-72.

- van der Voort P, Pijls BG, Nouta KA, Valstar ER, Jacobs WC, Nelissen RG. A systematic review and meta-regression of mobile-bearing versus fixed-bearing total knee replacement in 41 studies. Bone Joint J 2013; 95-B (9): 1209-16.

- Verra WC, van den Boom LG, Jacobs W, Clement DJ, Wymenga AA, Nelissen RG. Retention versus sacrifice of the posterior cruciate ligament in total knee arthroplasty for treating osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; 10: CD004803.