Abstract

Background and purpose — Surgical treatment of chronic acromioclavicular joint dislocations is challenging, and no single procedure can be considered to be the gold standard. In 2010, the GraftRope method (Arthrex Inc., Naples, FL) was introduced in a case series of 10 patients, showing good clinical results and no complications. We wanted to evaluate the GraftRope method in a prospective consecutive series.

Patients and methods — 8 patients with chronic Rockwood type III–V acromioclavicular joint dislocations were treated surgically using the GraftRope method. The patients were clinically evaluated and a CT scan was performed to assess the integrity of the repair.

Results and interpretation — In 4 of the 8 patients, loss of reduction was seen within the first 6 weeks postoperatively. A coracoid fracture was the reason in 3 cases and graft failure was the reason in 1 case. In 3 of the 4 patients with intact repairs, the results were excellent with no subjective shoulder disability 12 months postoperatively. It was our intention to include 30 patients in this prospective treatment series, but due to the high rate of complications the study was discontinued prematurely. Based on our results and other recent reports, we cannot recommend the GraftRope method as a treatment option for chronic acromioclavicular joint dislocations.

Surgical treatment of acromioclavicular joint (ACJ) dislocation sequelae is challenging, and no single procedure has been widely accepted as the gold standard. We have used both the modified Weaver and Dunn procedure, wire loops and hook plates. All gave acceptable results in many patients but there was also a high frequency of complications, as has been reported in numerous publications (CitationTaft et al. 1987, CitationBishop and Kaeding 2006, CitationMazzocca et al. 2007, CitationTamaoki et al. 2010).

In 2010, the GraftRope technique (Arthrex Inc. Naples, FL) was described and promising early results in a series of 10 patients were presented (CitationDeBerardino et al. 2010). The GraftRope device is a double endobutton construct held together by a continuous #5 FiberWire suture. A 12- to 15-cm tendon graft is double-folded and included in the device. The whole construct is then passed through—and secured—in a transclavicular, transcoracoid bone tunnel resembling the path of the coracoclavicular (CC) ligaments. The endobutton and FiberWire construct augments the repair, allowing the tendon graft to heal into place.

To our knowledge, there have been no prospective evaluations of the GraftRope method. Our aim was to include 30 patients treated with the GraftRope method in a prospective series with 2-year follow-up.

Patients and methods

From March 2011 to April 2012, we had operated on 8 patients with chronic, Rockwood type-III and type-V ACJ dislocations using the GraftRope method. The median age of the patients was 39 (22–63) years; 6 patients were men.

Inclusion criteria were: (1) chronic Rockwood type III–V ACJ dislocation with at least 6 months of non-operative treatment with unsatisfying result, and (2) patient age between 18 and 75 years. Exclusion criteria were: (1) major concomitant shoulder injury or disease on the affected side, (2) previous ACJ dislocation on the contralateral side, and (3) a mental or physical condition such that the patient was unable to follow the postoperative rehabilitation protocol.

All patients were followed up 3, 6, and 12 months after surgery, with clinical check-ups performed by a physiotherapist. All complications were documented. Shoulder function was assessed using the Disabilities of the Arm Shoulder and Hand (DASH) score and the Constant-Murley score. A computed tomography (CT) scan was performed 12 months postoperatively to evaluate the integrity of the repair.

The study protocol (Dnr 2012/545) was approved by the regional ethical review board in Lund and the study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration.

Surgery

For a detailed description of the surgical technique, see CitationCook et al. (2012). We used the same technique except that we used a 30-degree arthroscope instead of a 70-degree one, and we performed a distal clavicle excision in all cases and not just when reduction could not be achieved otherwise. Below is a summary of the method, with emphasis on the critical details of the procedure.

All operations were performed by 3 consultant orthopedic shoulder surgeons according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The patients were placed in the beach chair position and general anesthesia was given. In a bloodless field, a 3-cm incision was made on the medial side of the tuberosity of the tibia, the gracilis tendon was identified, and a 12- to 18-cm-long gracilis tendon graft was harvested. The graft was double-folded and prepared in the GraftRope construct.

Using a 30-degree arthroscope, standard diagnostic arthroscopy was performed, confirming that no other intra-articular pathology was present. The rotator cuff interval was opened and the coracoid visualized. An incision was made over the lateral clavicle and a distal clavicle excision performed. Through an anterior portal, the lower part of an aiming guide was introduced centering on the undersurface of the coracoid, the top part centering 30 mm medial to the ACJ on the clavicle. Maintaining this position, a guide wire was introduced through the drilling guide. Care was taken to place the entry and exit holes of the guide wire centrally on the top surface of the clavicle and the undersurface of the coracoid. Fluoroscopy was not used due to the good visualization of the entry and exit points of the guide wire and the fixed trajectory between these points ensured by the aiming guide.

A 6-mm cannulated drill was advanced over the guide wire to establish the transclavicular, transcoracoid bone tunnel through which the GraftRope construct was introduced. The FiberWire of the construct was tightened and tied over the clavicular button to reduce the dislocation, and an interference screw was used to secure the gracilis graft in the clavicular bone tunnel.

The shoulder was immobilized in a sling for 4 weeks, and during this time only passive range-of-motion exercises—up to 90 degrees of abduction and elevation—were performed. Thereafter, active range of motion was initiated. Strengthening exercises began 3 months postoperatively, free range of motion was permitted, and the patients were allowed to slowly return to full activity.

Results

The intention in this study was to treat 30 patients, evaluate their shoulder function at 3, 6, 12, and 24 months postoperatively, and present these data along with information on the frequency of early and late complications. However, within the first year postoperatively, 4 of our 8 patients had suffered a loss of reduction. Because of this high rate of complications, the trial was halted prematurely.

The reasons for loss of reduction were a coracoid fracture in 3 cases and graft failure in 1 case. Radiographs taken immediately after surgery showed that anatomical reduction had been achieved in all patients and there were no signs of loss of reduction or coracoid fractures. All failures were noted within the first 6 weeks postoperatively. No failures were due to trauma, and there was no evidence of patients not complying with the postoperative rehabilitation protocol. 1 of the patients who suffered a loss of reduction had pain and severely impaired shoulder function, and revision surgery was required. Of the other 3 patients with failed repairs, 1 felt that the shoulder symptoms were at the same level as preoperatively, and the remaining 2 experienced improvement despite the failure of their repairs. The CT scans performed 12 months postoperatively showed that 6 of 8 patients had a non-central drill hole in the coracoid.

3 of the 4 patients who did not have any complications showed excellent results. At 1 year postoperatively, these 3 patients had returned to their pre-injury level of activity and were satisfied with their shoulder function. 1 patient in this group still experienced pain when sleeping on the injured side and when lifting the injured arm above shoulder level. This patient had, however, improved compared to preoperatively. In this group, the median DASH score was 11 (4–29) and the median Constant-Murley score was 87 (68–92) 1 year after surgery.

Discussion

In the past decade, biomechanical research has suggested that anatomical repair with reconstruction of the ligaments supporting the ACJ is important to restore its properties. There have also been indications that biological healing of the reconstruction is important to achieve long term stability of the repair (CitationCostic et al. 2004). The GraftRope method allows a single tendon graft to be inserted in-between drill tunnels in the clavicle and the coracoid process. This provides a biological repair that more closely mimics the native anatomy than many previous techniques (CitationDeBerardino et al. 2010). Encouraged by the promising early results of this method, we designed and started our prospective study. Our results were, however, substantially different.

Since only 8 patients were treated using this method, it is possible that the surgeon learning curve affected the outcome. However, all procedures were performed by experienced shoulder arthroscopists who had also practiced the procedure in a laboratory setting.

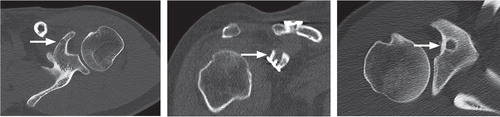

All but 1 of the losses of reduction were due to coracoid fracture. This leads us to assume that a 6-mm bone tunnel through the coracoid process compromises its strength sufficiently for a fracture to occur. In the CT scans performed within 1 year postoperatively, 6 of the 8 patients had a coracoid bone tunnel that was not centralized (Figure A–C). The average width of the coracoid is 15 mm, making a central tunnel placement crucial to preserve enough bone—both laterally and medially—to avoid fracture (CitationArmitage et al. 2011). Recent biomechanical testing has supported this further, by comparing tunnel placement in cadaver shoulders. 5 different tunnel placements were tested, and load to failure was measured and compared to undrilled controls. All tunnel placements except the completely central tunnel and one with a superior medial to inferior central orientation resulted in a significantly reduced load to failure (CitationFerreira et al. 2012).

Postoperative computed tomography scans displaying the position of the coracoid bone tunnel (marked by a white arrow) in 3 patients. A. A malpositioned medial tunnel breaching the medial cortex of the coracoid. B. A coronal plane view of a laterally placed bone tunnel. C. A transverse plane view of a laterally placed tunnel.

At drilling, the desire is to place the bone tunnel in a position originating and ending between the footprints of the 2 native CC-ligaments, thus mimicking their anatomy as much as possible. The arthroscopically assisted technique does not allow separate drilling of the coracoid and clavicle, so the positioning of one tunnel will inevitably affect the other. In a study comparing different tunnel placements in virtual models based on 3D-reconstructed CT images of the ACJ, it was shown that, using an arthroscopically assisted technique, it was not possible to achieve a near-anatomic tunnel through both the clavicle and the coracoid. The desired position of one tunnel would result in an unsatisfactory position of the other. That study also showed that the trajectory of a completely central coracoid tunnel would completely miss the clavicle in the majority of cases (CitationCoale et al. 2013). A similar study demonstrated that separate drilling of the clavicle and coracoid is necessary to achieve near-anatomic position of the bone tunnels and to avoid coracoid cortical breach (CitationXue et al. 2013). Based on these results, as well as our own experiences, we believe that the use of 6-mm bone tunnels and non-separate drilling of the clavicle and coracoid is associated with a substantial risk of fracture or tunnel misplacement.

Our study is not the first to present adverse results in patients treated with the GraftRope method or with other methods requiring a coracoid bone tunnel. CitationCook et al. (2012) presented adverse results in active-duty soldiers with ACJ dislocations treated with the GraftRope method. Reduction was lost in 8 of 10 cases; in 7 of these, the reason for the failed repair was suture slippage or breakage; only 1 patient suffered a coracoid fracture. Cook and colleagues suggested that a possible reason behind their high rate of failure was that they, like us, did not use the option to let the graft tails run over the ACJ and attach to the acromion. It is possible that this could prevent suture breakage by providing extra stability to the ACJ, but it is unlikely that this extra stability would prevent coracoid fracture, which was the most common complication seen in our material.

CitationMilewski et al. (2012) reviewed the GraftRope device further and presented a high rate of complications. In their study, 8 of 10 patients suffered a loss of reduction; both coracoid fractures and other modes of failure occurred. The authors considered transcoracoid drilling to be demanding, and possibly a procedure that not even the experienced surgeon is able to perform safely. The adverse results presented by CitationCook et al. (2012) and CitationMilewski et al. (2012) were not available when we started our study.

The difficulty of transcoracoid drilling is discussed further by CitationSchliemann et al. (2013). They treated 63 patients using a different surgical technique where the diameters of the bone tunnels were 4.5 mm. The drilling was performed using a drill guide in a straight trajectory fashion through the clavicle and coracoid. Despite the smaller diameter of the drill, 6 of the treated patients suffered a coracoid fracture.

Our study provides a detailed analysis of the difficulties of transcoracoid drilling. Based on the recent biomechanical and virtual-model research discussed above, together with the clinical and radiological follow-up of the patients in our series, we conclude that a 6-mm bone tunnel is not a safe way to provide an anchor point in the base of the coracoid process. We cannot recommend the GraftRope device as a treatment option for chronic ACJ dislocations.

JSN: study design, data analysis, and drafting of the manuscript. KEA and KL: study design and critical revision of the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

No competing interests declared.

We thank the Department of Physiotherapy, Helsingborg Hospital.

- Armitage MS, Elkinson I, Giles JW, Athwal GS. An anatomic, computed tomographic assessment of the coracoid process with special reference to the congruent-arc latarjet procedure. Arthroscopy 2011; 27 (11): 1485-89.

- Bishop JY, Kaeding C. Treatment of the acute traumatic acromioclavicular separation. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev 2006; 14 (4): 237-45.

- Coale RM, Hollister SJ, Dines JS, Allen AA, Bedi A. Anatomic considerations of transclavicular-transcoracoid drilling for coracoclavicular ligament reconstruction. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2013; 22 (1): 137-44.

- Cook JB, Shaha JS, Rowles DJ, Bottoni CR, Shaha SH, Tokish JM. Early failures with single clavicular transosseous coracoclavicular ligament reconstruction. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2012; 21 (12): 1746-52.

- Costic RS, Labriola JE, Rodosky MW, Debski RE. Biomechanical rationale for development of anatomical reconstructions of coracoclavicular ligaments after complete acromioclavicular joint dislocations. Am J Sports Med 2004; 32 (8): 1929-36.

- DeBerardino TM, Pensak MJ, Ferreira J, Mazzocca AD. Arthroscopic stabilization of acromioclavicular joint dislocation using the AC graftrope system. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010; 19 (2 suppl): 47-52.

- Ferreira JV, Chowaniec D, Obopilwe E, Nowak MD, Arciero RA, Mazzocca AD. Biomechanical evaluation of effect of coracoid tunnel placement on load to failure of fixation during repair of acromioclavicular joint dislocations. Arthroscopy 2012; 28 (9): 1230-36.

- Mazzocca AD, Arciero RA, Bicos J. Evaluation and treatment of acromioclavicular joint injuries. Am J Sports Med. 2007; 35 (2): 316-29.

- Milewski MD, Tompkins M, Giugale JM, Carson EW, Miller MD, Diduch DR. Complications related to anatomic reconstruction of the coracoclavicular ligaments. Am J Sports Med 2012; 40 (7): 1628-34.

- Schliemann B, Roßlenbroich SB, Schneider KN, Theisen C, Petersen W, Raschke MJ, Weimann A. Why does minimally invasive coracoclavicular ligament reconstruction using a flip button repair technique fail? An analysis of risk factors and complications. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2013 [ Epub ahead of print.]

- Taft TN, Wilson FC, Oglesby JW. Dislocation of the acromioclavicular joint. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1987; 69 (7): 1045-51.

- Tamaoki M JS, Belloti JC, Lenza M, Matsumoto MH, Gomes dos Santos JB, Faloppa F. Surgical versus conservative interventions for treating acromioclavicular dislocation of the shoulder in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2010; 8: CD007429.

- Xue C, Zhang M, Zheng TS, Zhang GY, Fu P, Fang JH, Li X. Clavicle and coracoid process drilling technique for truly anatomic coracoclavicular ligament reconstruction. Injury 2013; 44 (10): 1314-20.