Abstract

Background and purpose — Distal forearm fractures in children have excellent remodeling potential. The current literature states that 15° is the maximum acceptable angulation limit, though studies focusing on remodeling capacity above this value are lacking. We present data on the remodeling process in children with distal radius malunions with an angulation of ≥ 15°.

Patients and methods — Retrospectively, we radiographically evaluated the remodeling in 33 children (aged 3–14 years) with 40 distal radius fractures healed in ≥ 15° angulation in the dorsovolar (DV) plane (n = 32) and/or the radioulnar (RU) plane (n = 8). Malunion angulation at the start and at last follow-up was measured on AP and lateral-view radiographs. Mean follow-up time was 9 (3–29) months.

Results — All fractures showed remodeling. Mean DV malunion angulation was 23° (15–49) and mean RU malunion angulation was 21° (15–33). At follow-up, this had remodeled to mean 8° (–2 to 21) DV and 10° (3–17) RU. Mean remodeling speed (RS) was 2.5° (0.4–7.6) per month. There was a negative correlation between RS and remodeling time (RT) and a positive correlation between RS and malunion angulation. The relationship between RS and RT was exponential. RS was not found to be related to age or sex.

Interpretation — Remodeling speed decreases exponentially over time. Its starting value depends on the amount of angulation of distal radius fractures. This compensates for the increased need for remodeling in severely angulated fractures.

In a small percentage of common distal radius fractures in children, angular malunions will occur. Although corrective osteotomy is a treatment option in these cases, waiting is preferred because of the excellent potential for remodeling (CitationFriberg 1979b, CitationGascó and de Pablos 1997, CitationRang et al. 2005). However, the outcome of this remodeling is unclear since data on remodeling of these fractures are incomplete. Determinants of the remodeling potential are remodeling speed and the expected number of months of growth remaining (CitationGascó and de Pablos 1997). 2 articles have presented data on remodeling speed in distal forearm fractures. CitationFriberg (1979a,Citationb) found remodeling speed to be 0.9° per month on average in the dorsovolar plane. He also found that remodeling speed decreased with time, and that it is greater in greater angulations. He developed an exponential model with 2 parameters (angulation at the start as a constant and remodeling time as a negative exponent). If correct, this means that the higher remodeling speed in larger angulated fractures compensates at least in part for the greater amount of remodeling needed for correction. In his study, however, few patients had angulations greater than 15°.

Another study (CitationQairul et al. 2001) found higher values for average remodeling speed. However, the severity of the primary angulation was not reported and the study did not assess the relationship between remodeling speed and angulation or follow-up time. More detailed knowledge of remodeling speed of fractures with an angulation above 15° would be of value because conventional knowledge dictates that distal radius fractures with an angulation of 15–20° or more should be corrected, as this is beyond the potential for remodeling (CitationPrice et al. 1990, CitationPloegmakers and Verheyen 2006).

We assessed the process of remodeling of distal radius malunions with angulations over 15° in children, and the influence of angulation and healing time on remodeling.

Patients and methods

We retrospectively studied a subgroup of children treated for forearm fractures at our institute between 2001 and 2011. From 2,400 patients aged 1–16 years with a fractured forearm, we selected a study group using the following inclusion criteria: fracture of the distal one-third of the radius, treated only by immobilization using a cast, anterior-posterior (AP) and lateral radiographs available, healed in malunion with an angulation of 15° or more in the dorsovolar (DV) and/or the radioulnar (RU) plane, minimum follow-up of 2.5 months, and open distal radius epiphyseal plate at follow-up.

Children with pathological fractures were excluded. Patients with a follow-up time of more than 30 months were excluded because remodeling would possibly have stopped before the final radiograph (CitationDo et al. 2003). Inclusion of these cases would reduce the average speed over this length of time. We also excluded children with closure of the epiphyseal plate at follow-up, again meaning that a certain length of time without remodeling had occurred and that accurate estimation of remodeling speed would not be possible.

In some patients, new fractures occurred ipsilaterally on follow-up radiographs. We chose not to exclude these patients if the fracture did not intrude on the fracture we were studying. The only change in angulation in our patients occurred through remodeling.

Measurements

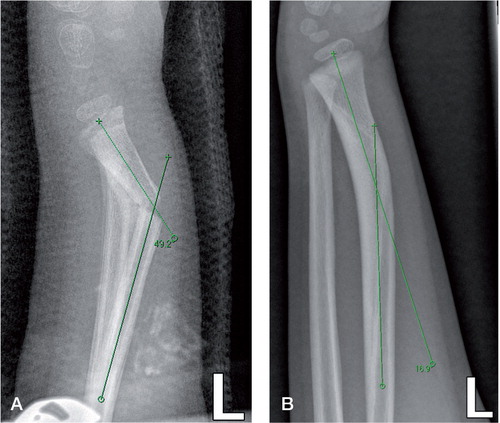

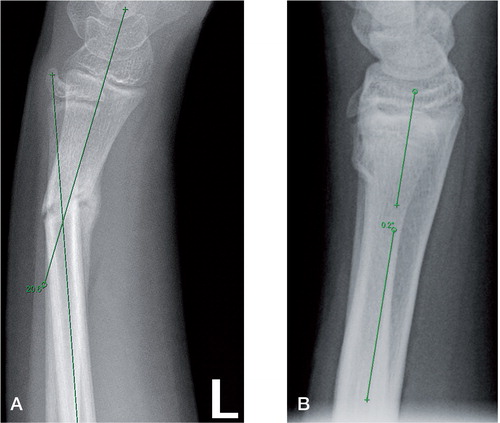

For angle measurements, the central longitudinal intramedullary axis was determined in both the proximal fragment and the (angulated) distal fragment as previously described by CitationHansen et al. (1976). The angle between these 2 axes was used as the angulation angle. DV and RU angulations were measured in the lateral and AP view, respectively, using the Cobb angle modus of the IMS viewing program (GE Healthcare, Slough, UK) ( and ). In all radiographs, the distal epiphyseal plates were visible at the time of fracture. Measurements were done by one researcher (TA) after inter-observer variability was found to be small, with a difference between 2 researchers of 3° (0–5) after 10 separate measurements. We did not measure the change in inclination of the distal radial epiphyseal plate.

Figure 1. Case 15. Measurement of the starting malunion angle (panel A) and the final malunion angle (panel B) as described by CitationHansen et al. (1976).

Figure 2. Case 28. A. Measurement of the starting malunion angle as described by CitationHansen et al. (1976). B. Measurement of the final malunion angle. New buckle fracture is present.

In some children, fractures were angulated at the start of treatment; in others, angulation occurred during the first week of immobilization—and in others, redislocation occurred some time after repositioning. We used the angulation in which the fracture was healed and this was defined as starting malunion angulation (A0). For follow-up evaluation, we used radiographs taken at the last outpatient visit.

The difference between starting malunion angulation (A0) and angulation at follow-up was defined as remodeling, measured in degrees. We defined remodeling time (RT) as follow-up time, measured in months. Because this was a retrospective study, follow-up times (i.e. RTs) differed. To allow comparison, remodeling speed (RS) per individual case was calculated by dividing the difference in angulation by the RT for that particular case, which was expressed in degrees per month.

We studied the relationship between RS on the one hand and RT, age at the time of fracture, sex, starting malunion angulation, and direction of angulation on the other.

Statistics

Data were analyzed using SPSS software. Results are presented as mean (SD).We used parametric tests to test the statistical significance of the difference in starting malunion angulation and the angulation at follow-up, between subgroups as well as for testing of correlations between RS, age, RT, and sex. To describe the relationship between RS and correlated variables, we used linear regression. Multiple regression was used to assess the combined effect of parameters on RS. Curve fitting was used to describe the non-linear relationship between RT and RS. Non-linear regression was used to test the model based on CitationFriberg (1979a) with our data. All tests were two-tailed and were considered significant at p-values < 0.05.

Ethics

The study was approved by the Medical Ethical Examination Committee of our institution (no. 2014.225).

Results

33 patients met our inclusion criteria (17 of them girls) (). 6 patients had separate values for DV and RU angulation because their fracture was angulated in the DV plane as well as in the RU plane. In the DV plane, 8 fractures were volarly displaced and 24 were dorsally displaced. All of the fractures in the RU plane were radially displaced. 1 patient was included twice since she had had both arms broken. This patient was the only double entry in our sample. With the inclusion of these 6 double measurements (DV and RU) and the 1 double entry, our analyses covered 40 wrists. In all cases studied, improvement in the primary fracture angulation was observed.

Table 1. Overview of patient data

Remodeling

There was a statistically significant difference between the starting malunion angulation (A0) and the final angulation in both the DV direction and the RU direction, with a mean difference of 15° (95% CI: 12–18, SD 8; p < 0.001, paired t-test) and 11° (95% CI: 5–18, SD 8; p = 0.004), respectively ().

Table 2. Descriptive statistics

Remodeling speed

Overall, we found a mean RS of 2.5° (0.36–7.6)/month (SD 2.0). Mean RS of the DV angulated fractures was 2.4° (0.36–7.6)/month (SD 1.8); for RU angulated fractures, this was 2.7° (0.97–7.6)/month (SD 2.0).

Using the independent-samples t-test, we did not find any statistically significant difference between the mean RS in RU angulated fractures (2.7°/month) and the mean RS in DV angulated fractures (2.4°/month) (p = 0.8). The mean RS values of volar dislocated fractures and of dorsal dislocated fractures were not significantly different either (p = 0.4).

Correlation and models

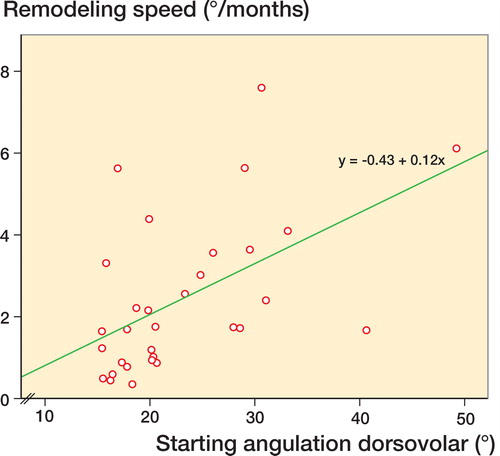

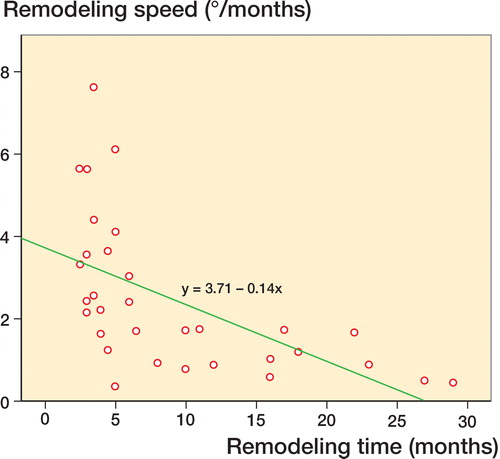

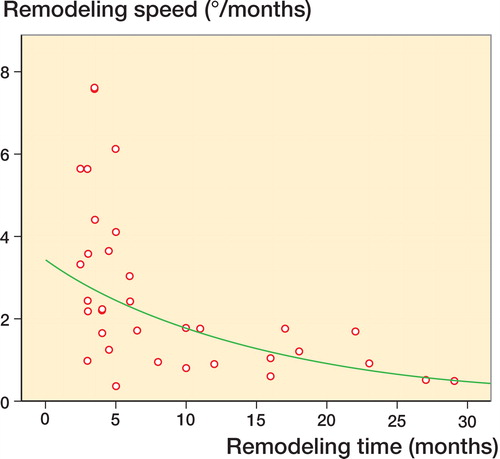

In the univariate analysis, there was a negative correlation between RS and RT and a positive correlation between RS and starting malunion angulation. There was no correlation between age and sex on the one hand and RS on the other ().

Table 3. Correlation with remodeling speed (RS)

Linear regression showed a significant relationship between RS and both RT (p = 0.001) and starting malunion angulation in the DV plane (p = 0.002) (see models 1 and 2 in ).

Table 4. Models describing the relationship between RS and independent parameters RT, and starting malunion angle (A0)

Using multiple regression, we found that both RT and starting malunion angulation DV were independently related to RS (p < 0.001 and p = 0.001) ( and ). In a linear function, these variables were able to predict the RS for 54% of the observed values (see model 3 in ). The relationship between RS and RT was better described by an exponential function (see model 4 in and ). A model based on the study by CitationFriberg (1979a), which combined A0 and an exponential function with RT, was significant with our data (see model 5 in ).

Discussion

Our study confirms the findings of Friberg: we found that RS is negatively but non-linearly related to RT, and positively related to starting malunion angulation DV. Furthermore, our study confirms his exponential model (CitationFriberg 1979a): the RS diminishes as remodeling progresses, and greater angulated fractures tend to remodel at a faster rate. When all fractures were included, we found a main RS of 2.5° (0.36–7.6)/month, which appeared to be irrespective of the direction of angulation. This value has already been confirmed by another study (CitationQairul et al. 2001). Our results mean, for instance, that a fracture in 30° angulation remodels with a speed of about 6° per month in the first month, decreasing to about 2° per month after 6 months and to almost 0° per month after 12 months ().Our findings show higher remodeling speeds than the CitationFriberg study (1979a). Possible reasons for this difference could be that, unlike in our study, Friberg measured the inclination of the epiphyseal plate rather than the fracture angulation, and that the angulations in his patients were smaller than in our patients. Like us, Friberg also reported a significantly greater RS in a subgroup of his study group with fractures angled in > 15°, with an RS of 1.9° per month compared to 0.9° per month overall. Differences in follow-up cannot be responsible, since most of his follow-up times were less than 12 months (based on in his study (CitationFriberg 1979a)), a time interval comparable to that in our study.

We also found that RS in the RU plane was not statistically significantly faster than in the DV plane, confirming the findings of CitationFriberg (1979a). However, since we only had 8 patients with an RU angulation, it is not possible to draw firm conclusions from this finding. The common idea is that DV angulation remodels better than RU angulation, as confirmed by CitationJohari and Maneesh (1999). But our results suggest that this difference may be small. We found no difference between dorsal and volar angulation remodeling, thus confirming results from another study (CitationZimmermann et al. 2004).

Because of our incomplete follow-up (that is, until there was complete remodeling), we cannot say whether remodeling would eventually be completed in angulations of this size. However, CitationGandhi (1962) found that 25 of 26 fractures in a comparable cohort had completely remodeled after 5 years.

For decision making on nonoperative treatment of distal radius fractures, the conventional acceptable angle is 25–30° in infants, declining to 6–14° in 15-year-olds according to CitationPloegmakers and Verheyen (2006). But different opinions exist as to whether or not age has great influence on remodeling potential. For RS of distal radius fractures, we found no significant difference between ages, thus confirming the findings of other studies (CitationGandhi et al. 1962, CitationFriberg 1979b, CitationJohari and Maneesh 1999). However, the size of our study group may have been insufficient to represent all age groups adequately. Taking the growth velocity reference values for Dutch children into account (CitationGerver and de Bruin 2003), the lack of influence of age as a confounder could also be explained by a relatively steady growth rate in this particular age group.

Some guidelines have proposed using the expected remaining growth years, with a cutoff point of 5 years for full remodeling based on the study by CitationGandhi et al. (1962), although the maximum complete RT found by CitationDo et al. (2003) in a study with angulations up to 15° was only 13 months. Although our study had insufficient data on the remodeling potential of children above 12 years, it suggests that 5 years of residual growth may not be necessary. This was also suggested earlier by CitationJohari and Maneesh (1999).

Gender does not appear to play a role in RS itself, although it should have a role in the management of these fractures—since girls appear to be 2 years ahead in maturing compared to boys (CitationPloegmakers and Verheyen 2006).

Our study had some limitations. It was small. We chose to limit our follow-up time to 30 months, although in an article by CitationDo et al. (2003) the mean RT needed for complete remodeling appeared to be only 4 months (with an average angulation of 14°), which means that the actual RS might even be greater than in our cohort with a mean RT of 9 months. Our findings were, however, mainly limited to the 5- to 12-year age group.

In conclusion, remodeling speed decreases exponentially over time. Its starting value is dependent on the amount of angulation of the malunion of the distal radius fracture. This compensates for the increased need for remodeling in severely angulated fractures. Our study confirms the exponential model suggested by CitationFriberg (1979a), with angulation of the malunion at the start as a constant and RT as a negative exponent.

KJ: data collection, analysis, and writing. TA: data collection. MW: writing. JSL: design, analysis, and writing.

We thank Dirk Knol of the Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics at our institute for advice.

- Do TT, Strub WM, Foad SL, Mehlman CT, Crawford AH. Reduction versus remodeling in pediatric distal forearm fractures: a preliminary cost analysis. J Pediatr Orthop B 2003; 12(2): 109–15.

- Friberg KS. Remodelling after Distal Forearm Fractures in Children: I. The Effect of Residual Angulation on the Spatial Orientation of the Epiphyseal Plates. Acta Orthop 1979a; 50: 537–46.

- Friberg KS. Remodelling after distal forearm fractures in children. III. Correction of residual angulation in fractures of the radius. Acta Orthop Scand. 1979b; 50: 741–9.

- Gandhi R, Wilson P, Mason Brown J, Macleod W. Spontaneous correction of deformity following fractures of the forearm in children. Br J Surg 1962; 50: 5–10.

- Gascó J, de Pablos J. Bone remodeling in malunited fractures in children. Is it reliable? J Pediatr Orthop Part B 1997; 6: 126–32.

- Gerver W J M, de Bruin R. Growth velocity: a presentation of reference values in Dutch children. Horm Res 2003; 60(4): 181–4.

- Hansen B, Greiff J, Bergman F. Fractures of the tibia in children. Acta Orthop Scand 1976; 47: 448–53.

- Johari AN, Maneesh S. Remodeling of forearm fractures in children. J Pediatr Orthop B 1999; 8: 84–7.

- Ploegmakers J J W, Verheyen C C P M. Acceptance of angulation in the non-operative treatment of paediatric forearm fractures. J Pediatr Orthop B 2006; 15(6): 428–32.

- Price CT, Scott DS, Kurzner ME, Flynn JC. Malunited forearm fractures in children. J Pediatr Orthop 1990; 10(6): 705–12.

- Qairul IH, Kareem BA, Tan AB, Harwant S. Early remodeling in children’s forearm fractures. Med J Malaysia 2001; 56 Suppl D: 34–7.

- Rang M, Stearns P, Chambers H. Radius and ulna. In: Rang’s children’s fractures (Ed. Rang M, Pring ME, Wenger D R).Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Philadelphia 2005; 3: 135–50.

- Zimmermann R, Gschwentner M, Pechlaner S, Gabl M. Remodeling capacity and functional outcome of palmarly versus dorsally displaced pediatric radius fractures in the distal one-third. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2004; 124: 42–8.