Abstract

Background and purpose — Hip dislocation in children with cerebral palsy (CP) is a common and severe problem. The Swedish follow-up program for CP (CPUP) includes standardized monitoring of the hips. Migration percentage (MP) is a widely accepted measure of hip displacement. Coxa valga and valgus of the femoral head in relation to the femoral neck can be measured as the head-shaft angle (HSA). We assessed HSA as a risk factor for hip displacement in CP.

Patients and methods — We analyzed radiographs of children within CPUP from selected regions of Sweden. Inclusion criteria were children with Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS) levels III–V, MP of < 40% in both hips at the first radiograph, and a follow-up period of 5 years or until development of MP > 40% of either hip within 5 years. Risk ratio between children who differed in HSA by 1 degree was calculated and corrected for age, MP, and GMFCS level using multiple Poisson regression.

Results — 145 children (73 boys) with a mean age of 3.5 (0.6–9.7) years at the initial radiograph were included. 51 children developed hip displacement whereas 94 children maintained a MP of < 40%. The risk ratio for hip displacement was 1.05 (p < 0.001; 95% CI 1.02–1.08). When comparing 2 children of the same age, GMFCS level, and MP, a 10-degree difference in HSA results in a 1.6-times higher risk of hip displacement in the child with the higher HSA.

Interpretation — A high HSA appears to be a risk factor for hip displacement in children with CP.

Hip dislocation in children with cerebral palsy (CP) is a common and severe problem. In almost all cases, the dislocation can be prevented by a surveillance program including radiographic examination of children at risk (CitationDobson et al. 2002, CitationHägglund et al. 2005b).

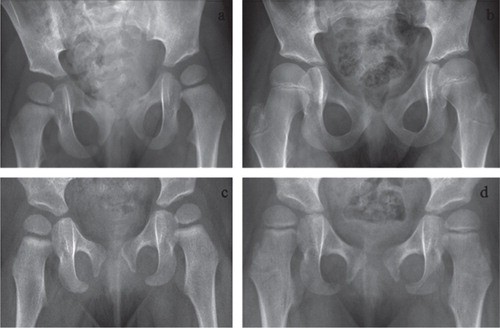

Hip displacement in CP is caused by an imbalance of forces acting on the hip joint, with strong and/or spastic hip flexors and adductors related to extensor and abductor muscles (CitationKalen and Bleck 1985). The femoral head is displaced laterally, and if not prevented, is finally dislocated. The Reimers’ migration percentage (MP) is a valid and reliable measure of hip displacement in CP (Reimers 1980), and probably the most commonly used. It describes the proportion of the femoral head that is positioned lateral to the acetabular margin (). Most reports define a hip with a MP of > 30–33% as being displaced and a hip with a MP of > 90–100% as being dislocated (Reimers 1980). Some hips with a MP of < 40% do not progress to dislocation, while almost all hips with a MP of > 40% need surgical intervention to prevent dislocation (CitationHägglund et al. 2007).

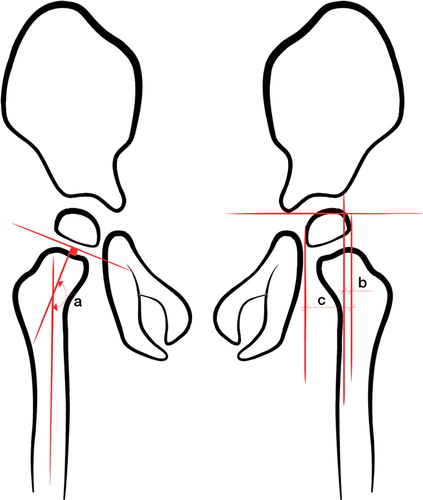

Figure 1. Measurement of the head-shaft angle (HSA), shown as a on the right hip, and the migration percentage (MP), calculated as b/c × 100, on the left hip.

Coxa valga is often seen in spastic hips (CitationLee et al. 2010), and can be measured as the neck-shaft angle (NSA) (CitationBobroff et al. 1999). In addition, the femoral head is often in valgus in relation to the femoral neck. The combination of these deformities can be measured as the head-shaft angle (HSA) (CitationSouthwick 1967) (). It has been shown that the HSA is increased in children with CP (CitationForoohar et al. 2009). Both NSA and HSA have shown excellent intra-rater and inter-rater reliability (CitationForoohar et al. 2009, CitationLee et al. 2010). In a bone model, CitationForoohar et al. (2009) found that the NSA was sensitive to inward or outward rotation of the femur, while measurement error was 5° or less for rotation of up to 45° for the HSA.

The Swedish follow-up program for CP, called CPUP (www.cpup.se), includes standardized monitoring of the children’s hips (CitationHägglund et al. 2005a and b). The MP of the hips, the child’s age, the type of CP, and clinical findings determine what type of treatment is used. Both the development of the MP over time and the current MP are analyzed. Children with a MP of < 33% are not treated with preventive surgery. Children with MP between 33% and 40% are usually followed closely and treated surgically if MP increases. As most children with MP > 40% will progress to dislocation if not treated surgically, this is most often an indication for surgery, which includes adductor-psoas tenotomy, varus osteotomy of the proximal femur, and/or pelvic osteotomy.

It is not clear whether there is an association between MP and HSA. If there is, this could be of importance when trying to identify patients with increased risk of developing hip dislocation. We have analyzed the development of MP related to HSA in children with cerebral palsy who were followed in CPUP.

Material and methods

In CPUP, the CP diagnosis is determined by a neuropediatrician at the age of 4 years according to Rosenbaum’s diagnosis criteria (Rosenbaum et al. 2007). Exclusion and inclusion criteria are in accordance with the Surveillance of Cerebral Palsy Network in Europe (SCPE) (CitationCans et al. 2000). Gross motor function is classified by the child’s physiotherapist according to the Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS), which is an age-related system with 5 levels ranging from I to V—where children with level V are affected most (CitationPalisano et al. 1997).

Children in CPUP at GMFCS levels III–V are followed with annual radiographic examinations from the age of first suspicion of CP. In the present study, radiographs from children in CPUP from southern and western Sweden (the counties of Skåne, Blekinge, Skaraborg, and Gothenburg with a population of 2.1 million) were analyzed. We used a standardized protocol for radiographic examination of the hips, according to the CPUP program, which every child in the present study was part of. We only included children at GMFCS levels III–V, with a first radiographic examination showing MP < 40% for both hips—either with at least 5 years of follow-up with the hips remaining below 40% without surgical treatment, or with hips that displaced (MP > 40%) within 5 years. The unit of analysis was the patient. The most affected hip at follow-up was used for analysis and the same hip was used for analysis at baseline.

The HSA is measured by drawing a line midway through the femoral shaft and then drawing another line perpendicular to the proximal femoral physis through the center of the proximal femoral epiphysis (). Migration index was measured as shown in .

Statistics

We examined the risk of hip displacement with MP > 40% for either hip within 5 years related to the HSA at the first radiographic examination. The risk ratios (RRs) between children differing in HSA by 1 degree and corresponding 95% CIs were calculated and corrected for potential confounders (MP at first examination, GMFCS, and age at first examination) using Poisson regression with robust error variance, according to CitationZou (2004). The Wald test was used to test the null hypothesis of no effect of HSA on the risk of hip displacement. Any p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Calculations were done using STATA 12 software.

Ethics

The study was approved by the Medical Research Ethics Committee of Lund University (LU-443-99).

Results

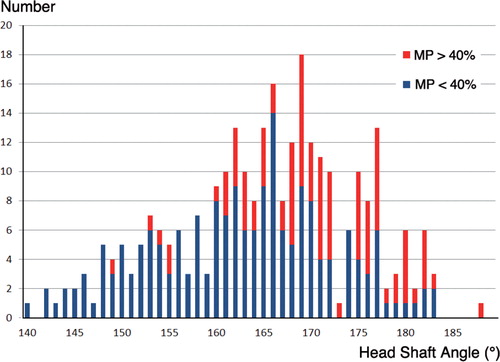

145 children (73 boys) fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were included in the analyses. Mean age at the first radiographic hip examination was 3.5 (0.6–9.7) years. 29 children had GMFCS level III, 62 had level IV, and 54 had level V. Of the 145 children, 51 developed a hip displacement with a MP of > 40% during the 5-year follow-up and 94 remained with MP below 40% for at least 5 years. The mean HSA of all measurements was 166 (140–189)° (). No children were excluded because of poor quality of the radiographs.

Figure 2. Distribution of the head-shaft angle (HSA). Blue represents the group that stays with MP < 40% for at least 5 years. Red represents the group that develops hip displacement with MP > 40% within 5 years.

The 51 children who developed hip displacement with an MP of > 40% were 2.6 (0.7–7.0) years old on average at the time of the first radiographic examination. They had an initial mean MP of 23% (0–39) and a mean HSA of 171 (154–189)°. 4 children had GMFCS level III, 14 had level IV, and 33 had level V. Mean age at the time of hip displacement with MP > 40% was 5.1 (1.9–10.8) years and the mean HSA was 172 (150–183)° .

The 94 children who did not develop displacement with MP > 40% were 3.8 (0.6–9.7) years old on average at the first examination. They had an initial mean MP of 16 (0–39)% and a mean HSA of 166 (146–182)°. 25 children had GMFCS level III, 48 had level IV, and 21 had level V. After 5 years, they had a mean MP of 23 (0–39)% and a mean HSA of 159 (140–183)°.

HSA was a risk factor for developing hip displacement independently of age at examination, GMFCS, and MP, where hip displacement was defined as MP > 40% within 5 years. There was no statistically significant interaction between MP and HSA (Wald test, p = 0.3). The RR for hip displacement in the corrected analysis was 1.05 (CI: 1.02–1.08, p < 0.001). This means that when comparing 2 children of the same age, the same GMFCS level, and the same MP in the most displaced hip, but with a 10-degree difference in HSA, the child with the higher HSA would have a 1.6-times higher risk of hip displacement ().

Discussion

We found that HSA predicts the risk of hip displacement in children with CP. The study was based on the total population of children with CP in a defined area, which means that our results can be generalized to other children with CP with the same characteristics.

One limitation was that the radiographic examinations were performed with the femur positioned in the frontal plane. The images were consequently not adjusted for different degrees of anteversion. However, using a bone model, CitationForoohar et al. (2009) have shown that the measurement error is 5° or less for femoral rotation of up to 45°. If differences in the rotational position of the femur had an important effect on the measurement error of the HSA, it would reduce statistical precision in the relative risk estimate, resulting in wider confidence intervals and reduced statistical power, thus making it more difficult to detect a potential effect. An angle close to 180° is less sensitive to rotation than a lower angle. The NSA is normally 140°–145° (CitationLee et al. 2010), and the mean HSA in our study was 165°–171°. This supports the idea that HSA is less sensitive to rotation than NSA. As only 8 children developed MP of > 40% in both hips, the association could not be calculated for the less affected hip.

To our knowledge, there have been no publications describing the normal values of HSA related to age. The NSA is known to decrease with age (Shands and Steele 1958), suggesting that the HSA would also normally decrease with age. In the present subgroup with displaced hips, the mean HSA was higher and remained at the same level (171°–172°). The subgroup in which the hips did not displace had a lower initial HSA, and the mean HSA decreased from 166° to 159° during the time of follow-up. In a study by CitationForoohar et al. (2009), 15 children with spastic CP had a mean HSA of 161° whereas 10 children with hips planned for preventive surgery had a mean HSA of 170°. The relationship between HSA and the degree of displacement was not examined. CitationLee et al. (2010) analyzed the MP, NSA, and HSA in 384 patients with CP, mean 9.1 (3–17) years of age, 129 of whom had GMFCS III–V. HSA increased from 152° in children with GMFCS level I to 162° in those with GMFCS level V.

The inter-rater reliability for measurement of HSA was excellent in the study by CitationForoohar et al. (2009) (ICC = 0.94, 95% CI: 0.86–0.98). CitationLee et al. (2010) demonstrated a somewhat lower reliability (ICC = 0.79, 95% CI: 0.59–0.90). The material of Lee et al. included children up to 17 years of age, some of whom did not have a well-demarked growth plate. Similar to different degrees of anteversion, a lower reliability would make it more difficult to detect an effect of HSA and produce wider confidence intervals for the RR estimate in our study.

There are probably other risk factors for hip displacement, such as range of hip motion, degree of spasticity, and CP subtypes. These factors should be considered when deciding on treatment in the individual child. CP subtype is, however, sometimes difficult to classify before 4 years of age. Our study shows that in the absence of information on these additional risk factors, HSA provides information on the risk of hip displacement.

It is well known that growth is influenced by mechanical stresses, such as compression and tension, according to the Hueter-Volkmann Law (CitationStokes 2002). The orientation of the physis reflects the direction of growth; hips with a higher HSA have an unfavorable growth direction and a higher risk of lateral displacement. Surgery with varus osteotomy to prevent hip dislocation results in a recentralization of the femoral head, but also a decrease in the HSA with a more favorable direction of growth of the femoral head. This is in accordance with CitationForoohar et al. (2009) and CitationLee et al. (2010); both of these papers have discussed the possible clinical importance of re-establishing the normal HSA by a varus osteotomy.

In conclusion, this study shows that a high head-shaft angle increases the risk of hip displacement in children of GMFCS level III–V with cerebral palsy. The HSA may be used as a complement to age, GMFCS, MP, and clinical examination when deciding on future radiographic examination and treatment. The HSA is not sensitive to rotation of the femur and may be useful in hip-screening programs.

All the authors designed the study, revised the manuscript, and approved the final draft. MH wrote the first draft and PW performed the statistical analyses.

The study was supported by grants from the Faculty of Medicine, Lund University, and Stiftelsen för bistånd åt rörelsehindrade i Skåne.

No competing interests declared.

Notes

- Bobroff ED, Chambers HG, Sartoris DJ, Wyatt MP, Sutherland DH. Femoral anteversion and neck-shaft angle in children with cerebral palsy. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1999; (364): 194-204.

- Cans C, Guillem P, Baille F. Surveillance of cerebral palsy in Europe: a collaboration of cerebral palsy surveys and registers. Surveillance of Cerebral Palsy in Europe (SCPE). Dev Med Child Neurol 2000; 42 (12): 816-24.

- Dobson F, Boyd RN, Parrott J, Nattrass GR, Graham HK. Hip surveillance in children with cerebral palsy. Impact on the surgical management of spastic hip disease. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2002; 84 (5): 720-6.

- Foroohar A, McCarthy JJ, Yucha D, Clarke S, Brey J. Head-shaft angle measurement in children with cerebral palsy. J Pediatr Orthop 2009; 29 (3): 248-50.

- Hägglund G, Andersson S, Duppe H, Lauge-Pedersen H, Nordmark E, Westbom L. Prevention of severe contractures might replace multilevel surgery in cerebral palsy: results of a population-based health care programme and new techniques to reduce spasticity. J Pediatr Orthop B 2005a; 14 (4): 269-73.

- Hägglund G, Andersson S, Düppe H, Lauge-Pedersen H, Nordmark E, Westbom L. Prevention of dislocation of the hip in children with cerebral palsy. The first ten years of a population-based prevention programme. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2005b; 87 (1): 95-101.

- Hägglund G, Lauge-Pedersen H, Persson M. Radiographic threshold values for hip screening in cerebral palsy. J Child Orthop 2007; 1 (1): 43-7.

- Kalen V, Bleck EE. Prevention of spastic paralytic dislocation of the hip. Dev Med Child Neurol 1985; 27 (1): 17-24.

- Lee KM, Kang JY, Chung CY, Kwon DG, Lee SH, Choi IH, Cho TJ, Yoo WJ, Park MS. Clinical relevance of valgus deformity of proximal femur in cerebral palsy. J Pediatr Orthop 2010; 30 (7): 720-5.

- Palisano R, Rosenbaum P, Walter S, Russell D, Wood E, Galuppi B. Development and reliability of a system to classify gross motor function in children with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol 1997; 39 (4): 214-23.

- Reimers J. The stability of the hip in children. A radiological study of the results of muscle surgery in cerebral palsy. Acta Orthop Scand 1980; Suppl 184: 1-100.

- Rosenbaum P, Paneth N, Leviton A, Goldstein M, Bax M, Damiano D, Dan B, Jacobsson B. A report: the definition and classification of cerebral palsy April 2006. Dev Med Child Neurol Suppl 2007; 109: 8-14.

- Shands A RJr, Steele MK. Torsion of the femur; a follow-up report on the use of the Dunlap method for its determination. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1958; 40-A (4): 803-16.

- Southwick WO. Osteotomy through the lesser trochanter for slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1967; 49 (5): 807-35.

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 12. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP. 2011.

- Stokes IA. Mechanical effects on skeletal growth. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact 2002; 2 (3): 277-80.

- Zou G. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol 2004; 159 (7): 702-6.