Abstract

Background and purpose — Muscle atrophy is seen in patients with metal-on-metal (MOM) hip implants, probably because of inflammatory destruction of the musculo-tendon junction. However, like pseudotumors, it is unclear when atrophy occurs and whether it progresses with time. Our objective was to determine whether muscle atrophy associated with MOM hip implants progresses with time.

Patients and methods — We retrospectively reviewed 74 hips in 56 patients (32 of them women) using serial MRI. Median age was 59 (23–83) years. The median time post-implantation was 83 (35–142) months, and the median interval between scans was 11 months. Hip muscles were scored using the Pfirrmann system. The mean scores for muscle atrophy were compared between the first and second MRI scans. Blood cobalt and chromium concentrations were determined.

Results — The median blood cobalt was 6.84 (0.24–90) ppb and median chromium level was 4.42 (0.20–45) ppb. The median Oxford hip score was 34 (5–48). The change in the gluteus minimus mean atrophy score between first and second MRI was 0.12 (p = 0.002). Mean change in the gluteus medius posterior portion (unaffected by surgical approach) was 0.08 (p = 0.01) and mean change in the inferior portion was 0.10 (p = 0.05). Mean pseudotumor grade increased by 0.18 (p = 0.02).

Interpretation — Worsening muscle atrophy and worsening pseudotumor grade occur over a 1-year period in a substantial proportion of patients with MOM hip implants. Serial MRI helps to identify those patients who are at risk of developing worsening soft-tissue pathology. These patients should be considered for revision surgery before irreversible muscle destruction occurs.

MRI is useful in following up patients with metal-on-metal (MOM) hip implants because it identifies soft-tissue abnormalities. Muscle atrophy forms part of the exaggerated inflammatory response to metal wear debris, and it is thought to reduce function (CitationPandit et al. 2008). Other abnormalities include abductor tendon avulsion, pseudotumor, periprosthetic fluid collections, and synovial thickening (CitationToms et al. 2008, CitationSabah et al. 2011, CitationHayter et al. 2012, Hart 2013).

The UK Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), the European consensus report, and the US Food and Drugs Administration (FDA) all recommend cross-sectional imaging (MRI) of patients with MOM hip implants. These agencies also recommend that patients should be followed up for the life of the implant. However, it is currently unclear how to interpret MRI findings of muscle atrophy.

The outcome after revision surgery of a MOM hip is worse than that after revision of a non-MOM hip because of the soft-tissue destruction. It may be possible to improve the outcome through early investigation and management of patients who are at risk of soft-tissue destruction. Several studies have found muscle atrophy prevalence ranging from 22% to 90% (CitationToms et al. 2008, CitationSabah et al. 2011, CitationHayter et al. 2012). Pseudotumors are also believed to cause local destruction, and their prevalence can range from 0.1% to 69% (CitationPandit et al. 2008, Canadian Hip Resurfacing Study 2011, CitationSabah et al. 2011, CitationChang et al. 2012, CitationHart et al. 2012).

The wide-ranging prevalence of soft-tissue abnormality is believed to be due in part to the variable response of soft tissues to MOM hips, but also to the effect of time. Understanding whether muscle atrophy can progress with time will help to identify patients who need repeat MRI, revision surgery, or intensive monitoring. Recent studies have assessed the serial progression of soft-tissue pathology, but they have concentrated on pseudotumor progression (CitationAlmousa et al. 2013, Ebreo et al. 2013, van der Weegen et al. 2013). There have been no studies assessing changes in muscle atrophy after MOM hip arthroplasty using MRI analysis.

Our aim was to improve the interpretation of muscle changes seen in MOM hips by MRI. Our hypothesis was that muscle atrophy would not show progression in MRI results taken at 2 different times.

Methods

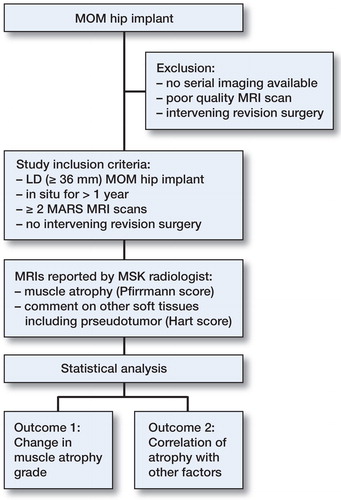

We designed a cohort study to examine any change in MRI findings over time. We retrospectively reviewed patients from our database of patients with MOM hip implants who had been discussed at our tertiary referral center. We operate a multi-disciplinary team (MDT) meeting consisting of an expert panel of hip revision surgeons and musculoskeletal radiologists who meet on a weekly basis to discuss the management of patients with MOM hip implants. We selected those patients who fulfilled our inclusion criteria ().

All patients with 2 available metal artifact reduction sequence (MARS) MRI scans without any previous or intervening revision surgery were considered. 74 hips in 56 patients fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were included in the study. These included hips of several current-generation designs, including total hip arthroplasty and hip resurfacing types (Table 1, see Supplementary data).

The median age was 59 (23–83) years and 32 patients were women. 46 hip resurfacings and 28 modular stemmed prostheses constituted the cohort. 51 hips had been implanted using a posterior surgical approach to the hip, 21 hips via a lateral approach, and the approach was unknown in 2 cases (performed overseas). We re-examined 128 MRI scans of the 74 hips. The median time since implantation was 83 (35–142) months. Clinical details of the patients were also collected, including age, sex, blood cobalt levels, blood chromium levels, and Oxford hip score.

The reasons for repeat MRI scanning included monitoring of a pseudotumor in an asymptomatic patient (n = 12), monitoring of muscle atrophy in an asymptomatic patient (n = 2), high ion levels in an asymptomatic patient (n = 3), high ion levels and pseudotumor in an asymptomatic patient (n = 7), increasing symptoms (n = 39), and increasing symptoms in the presence of high metal ion levels (n = 11).

MRI scans were obtained using the MARS protocol (). A senior musculoskeletal radiologist (MK), with experience in reporting MARS MRI scans on patients with MOM hip implants, reported all scans. The reader was blind to the clinical symptoms of the patient and reported the scans randomly without referring to the first scan. The scans were then interpreted in consensus between the radiologist and the senior surgeons (JS and AH) during the multi-disciplinary team meeting. Cohen’s kappa was run to determine whether there was agreement between our 2 radiologists (one of them MK), who both regularly dual-report MRI scans and present their findings to our multi-disciplinary meeting. There was moderate agreement (κ = 0.463; p < 0.001) using Landis and Koch criteria (CitationLandis and Koch 1977).

Table 2. MARS MRI protocol

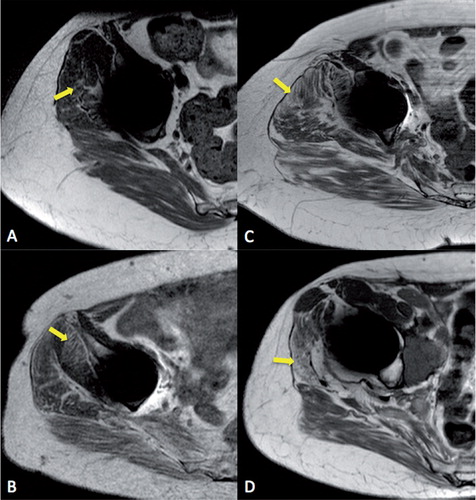

Muscle atrophy was defined as a decrease in volume and appearance of fatty change according to the grading system proposed by CitationPfirrmann et al. (2005). Grade 0–4 was allocated to the illiopsoas, gluteus minimus, gluteus medius (divided into anterior, middle, posterior, and inferior portions), and gluteus maximus individually (). Muscle tendon disruption was reported where there was discontinuity of the muscle attachment, and it was described as being either partial or complete.

Figure 2. MRI demonstrating increasing grades of muscle atrophy in MOM hip patients. A. Grade 1. B. Grade 2. C. Grade 3. D. Grade 4. Areas of significant atrophy are highlighted with arrows.

Other soft-tissue abnormalities were reported if present. These included collections of bursal fluid, tendon injuries, and presence of pseudotumor.

Pseudotumor presence and grade was defined according to a previously published classification (CitationHart et al. 2012). Pseudotumor volume was measured electronically in all 3 dimensions. The formula for an elliptical volume was used: volume (V, cm3) = height (H) × width (W) × depth (D) × 0.52. If more than one pseudotumor was present, the combined volume was used for the analysis.

Statistics

Demographics variables are reported as mean (range) and outcome variables as mean (SD). All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 21. Significance was assumed with p-values ≤ 0.05.

Change in muscle atrophy over time.

Muscle scores for each muscle section were considered separately.

Paired-samples t-tests were used to compare the change in muscle atrophy grade for each named muscle individually between the first and second MRI scans.

Change in other soft-tissue abnormalities over time.

Paired-samples t-tests were used to compare change in presence of bursal fluid collection, presence of tendon injury, presence of pseudotumor, grade of pseudotumor, and size of pseudotumor between the first and second MRI scans.

Analysis to assess for interclass correlation, on the basis that patients with bilateral hip implants were included in the cohort.

Interaction with demographic factors including age, sex, blood cobalt levels, blood chromium levels, and Oxford hip score was undertaken using an ANOVA analysis.

Demographics (except implant type and sex) were categorized for the purposes of these analyses, as follows:

Implant type: resurfacing vs. modular THR.

Age: < 60 or ≥ 60 years.

Male vs. female.

Cobalt ppb: < 7 or ≥ 7 (as per MHRA threshold).

Chromium ppb: < 7 or ≥ 7 (as per MHRA threshold).

Oxford hip score (3 groups):

Mild symptoms, ≥ 42.

Moderate symptoms, 20–41.

Severe symptoms, < 20.

Hypothesis-driven multivariate analysis using ANCOVA was undertaken to assess the following hypothesis:

Muscle atrophy does progress with age.

Progression of muscle atrophy is not sex-specific.

Muscle atrophy does increase in patients with metal (cobalt) ion levels > 7ppb.

Muscle atrophy progresses in those patients with a low Oxford hip score.

Ethics

Approval for this study was obtained from the Royal National Orthopaedic Hospital NHS institutional review board (R&D reg. number: SE.13.030).

Results

The median blood cobalt ion level was 6.8 (0.24–90) ppb and the median chromium level was 4.4 (0.20–45) ppb. Median Oxford hip score was 34 (5–48) (Table 1, see Supplementary data). 10 patients (13 hips) were asymptomatic (OHS > 41), and half of them had blood cobalt ion levels greater than the 7-ppb threshold set by the MHRA.

Muscle atrophy

Gluteus minimus atrophy was seen in 54 of 74 hips within the cohort, where 45 suffered atrophy of grade 2 or above. Posterior gluteus medius muscle atrophy was seen in 35 hips, where 15 hips had atrophy of grade 2 or above. The results were normally distributed.

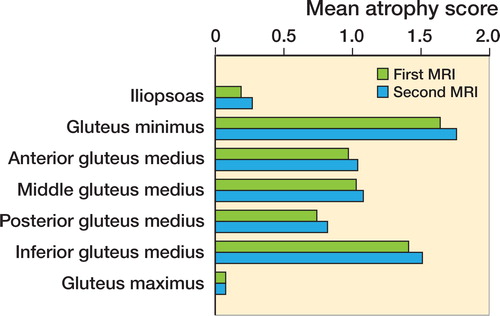

The mean atrophy scores from time point 1 (first MRI) to time point 2 were assessed using paired-samples t-tests. The mean atrophy values were seen to increase in all cases (Table 3, see Supplementary data). A statistically significant difference was seen for gluteus minimus, gluteus medius posterior portion, and also gluteus medius inferior portion.

The change in the mean atrophy score for gluteus minimus was 0.12 (SD 0.3; p = 0.002). Despite an increase in the mean atrophy scores for the anterior and middle portions of the gluteus minimus muscles, neither of these reached significance. With regard to the gluteus medius posterior portion, the change in the mean score was 0.08 (SD 0.3; p = 0.01). For the inferior portion, a change of 0.10 (SD 0.5; p = 0.05) was seen (Table 3, see Supplementary data and ). Regarding the cases with progressive posterior gluteus medius atrophy (n = 6), the mean blood chromium ion level was 11 (3.2–25) ppb and the mean cobalt ion level was 21 (3.7–51) ppb. The median Oxford hip score for these patients was 27 (8–42) out of a maximum possible score of 48. Atrophy scores for iliopsoas and gluteus maximus were similar (p = 0.2).

Interclass correlation

The cohort consisted of 74 hips in 56 patients. 36 patients had 1 MOM hip and the remaining 18 had bilateral MOM hips. 14 of these 18 patients had had their MOM hips implanted at different time points. In such cases, the first hip was taken and the second one was excluded. For the remaining 4 patients who had had both hips implanted at the same time, 1 of the 2 hips was randomly selected to be included in the analysis and the other was excluded. This approach has been advocated by CitationBryant et al. (2006). Analysis of this smaller sample size revealed similar results, where a significant increase in the mean atrophy of the gluteus minimus—of 0.12 (SD 0.3)—was seen (p = 0.007), and there was a change in atrophy of the posterior portion of the gluteus medius of 0.07 (SD 0.3; p = 0.04). The remaining muscle portions did not show any statistically significant difference.

Furthermore, when controlling for time between implantation and first MRI and also time between MRI scans, and after all duplicates had been excluded (i.e. so that each case with bilateral hips was represented only once), no statistically significant results were seen. However, this was limited by the small sample size and the results are probably inconclusive.

Other soft-tissue abnormality

Increased bursal fluid and tendon disruption was seen over time, but this was not statistically significant (Table 4, see Supplementary data). Tendon disruption was present in 24 hips, and a median Oxford hip score of 34 (8–45) was seen in this subgroup of patients. 17 disruptions were partial tears and the remaining 7 were complete tears. 2 partial tears had developed in patients with normal MARS MRI images on first scanning—involving the gluteus medius and the iliopsoas tendon, respectively.

Of the partial tears, the gluteus medius only was affected in 12 patients, the gluteus medius and minimus were affected in 4 patients, and the iliopsoas was affected in only 1 patient. Complete tendon disruptions involved both the gluteus medius and minimus tendons in 5 patients, and they involved the gluteus medius only in 2 patients. The median Oxford hip score for the partial tear subgroup was 34 (8–43), and that for the complete tear subgroup was 34 (8–45).

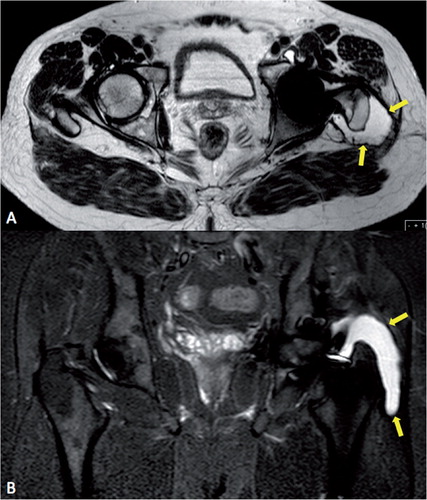

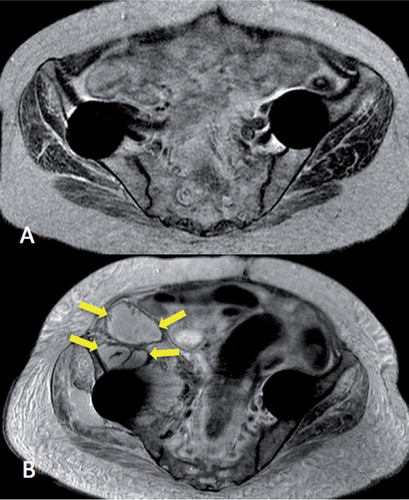

Interestingly, 6 of the 7 hips with complete tendon disruption had antero-lateral pseudotumors causing stripping of the insertion of the abductor tendon from the greater tuberosity (Table 5, see Supplementary data, and ).

Pseudotumor

41 of the 47 hips had a pseudotumor on MRI examination. However, of these 41 pseudotumors, 36 were present at the time of the first MRI, median 65 (5–131) months after implantation.

The development of new pseudotumors was seen, but this did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.08). The number of patients who had multiple pseudotumors in more than one location around the hip did increase significantly (p = 0.05). The grade of pseudotumors also increased significantly, with a mean increase in grade of 0.18 (SD 0.6; p = 0.02). There was no significant increase in pseudotumor size over time.

When analyzed individually, 5 hips developed new pseudotumors within the observation period (), and 7 hips had an increased grade. Progression of all types of pseudotumor grade was seen, with 2 hips changing from type 1 to type 2A, 4 hips changing from type 2A to type 2B, and 1 hip changing from type 2B to type 3. On the other hand, 2 hips regressed in pseudotumor grade, where 1 changed from type 3 to type 2B, and the other changed from type 2B to type 2A.

Figure 5. Example of new pseudotumor formation (arrows) in a patient with bilateral Birmingham hip resurfacing. T2-weighted MRI images. Date of implantation was January 2007, time from operation to first MRI (panel A) was 69 months, and time from operation to second MRI (panel B) was 84 months.

In the 12 hips in which new or progressive pseudotumor change was seen, the median time for the change to occur (time from implantation to MRI in which the change was seen) was 59 (20–104) months. The median time to develop a new pseudotumor was 59 (42–79) months. Median and mean blood chromium in these patients was 6.6 ppb, and for cobalt these values were 6.2 and 7.2 ppb, respectively. Similarly, the median and mean OHS values in these patients were 30 and 29, respectively.

Interaction with patient factors

The changes over time were assessed to determine whether an association existed with implant type, patient age and sex, blood cobalt and chromium levels, and patients’ clinical function scores (Oxford hip score; Table 6, see Supplementary data).

The increased atrophy seen at the inferior portion of gluteus medius was statistically significantly associated with implant type. Patients with a resurfacing implant were more likely to have increasing atrophy of the inferior portion of the medius muscle (p = 0.04).

Age less than 60 years contributed to increasing atrophy of the gluteus minimus (p = 0.02). Gender contributed to increased progression of atrophy of the middle portion of the gluteus medius, as male patients had a significant association (p = 0.02). However, the implications of this finding are unclear.

No statistically significant relationships were found between blood cobalt levels, blood chromium levels, or patient function on the one hand and changes in muscle atrophy on the other.

Multivariate analysis using hypothesis-driven ANCOVA analysis revealed similar findings to the above. Atrophy of the gluteus minimus increased with age (p = 0.002) and atrophy of the middle portion of the gluteus medius was more common in female patients (p = 0.022). No correlation between surgical approach, blood metal ion levels, and Oxford hip score was seen with progressive muscle atrophy.

Discussion

Our study is limited by the retrospective review of data, where time intervals between scans were not standardized, but this was factored into our statistical analysis. Secondly, there was an element of selection bias since patients were recruited from a MOM hip multi-disciplinary team meeting held in our tertiary center, to which patients are referred for second opinions. Thus, our findings may not be representative of the whole MOM hip population. However, they are likely to be relevant to those patients for whom management decisions are most difficult. A further limitation of the present study is the knowledge that muscle atrophy can be associated with joint pathology such as osteoarthritis (CitationGrimaldi et al. 2009), the degree of which is unknown in our group of patients due to the lack of protocol for preoperative MRI scanning. Lastly, our study may have been limited by its small sample size since further analysis after removing bilateral hips failed to show the same statistical significance for progressive muscle changes.

MARS MRI has been optimized for viewing of the soft tissues surrounding metal hip implants. Despite some remaining artifacts, it enables excellent differentiation of soft and hard tissues (CitationNawabi et al. 2014). Our experience supports the use of MARS MRI for the assessment of soft-tissue pathology, in line with MHRA and FDA recommendations.

It is clear from the present study that muscle atrophy is common in patients with MOM hip implants, as three-quarters of the hips had gluteus minimus atrophy and half of them had posterior gluteus medius atrophy. We found an increase in atrophy of the posterior and inferior portions of the gluteus medius, and also of the gluteus minimus over time. 11 of 74 hips had an increase in gluteus minimus atrophy, and 6 of 74 hips had an increase in posterior gluteus medius atrophy. We found that the patients with progressive posterior-portion atrophy were more likely to be female and to have metal ion levels greater than 7 ppb. Gender also had an effect on progressive atrophy of the middle portion of the gluteus medius, but considering the group as a whole, progressive atrophy of this portion of the gluteus medius was not statistically significant. This may have been due to an insufficient sample size, since the patient-specific factors that have an effect on MOM hips and muscle atrophy are not clearly defined in the literature.

Various research groups have reported the presence of muscle atrophy around MOM hips (CitationToms et al. 2008, CitationHayter et al. 2012, Hart 2013). CitationToms et al. (2008) found gluteus medius atrophy in 8 of 20 symptomatic hips, and gluteus minimus atrophy in 9. It is believed that such atrophy may follow on from the use of transgluteal surgical approaches (CitationMadsen et al. 2004), but the presence of gluteal atrophy in patients treated through a posterior approach suggests that this is related to the metal-based disease process (Hart 2013). This is not to say that muscle atrophy is never seen in conventional THA patients (CitationPfirrmann et al. 2005), but there have not been any studies showing progression of muscle atrophy in such patients.

We identified stripping of the abductor tendon (gluteus medius and minimus) from its insertion, secondary to a pseudotumor, in 6 hips. Tendon avulsion after hip arthroplasty is a recognized complication (CitationDrexler et al. 2014), although the prevalence of this problem is unknown. CitationFang et al. (2008) previously suggested that periarticular inflammatory collections develop along the path of least resistance, which in the native hip would include the iliopsoas bursa and laterally into the trochanteric bursa. The surgical approach could possibly introduce spaces, which might explain why pseudotumors are often located in various positions around a MOM hip, including posteriorly. Furthermore, tendon avulsion has been reported in hips following hip arthroplasty—implanted through anterolateral and transgluteal approaches (CitationPfirrmann et al. 2005, CitationToms et al. 2008). In our series, however, we saw abductor tendon stripping from both the anterolateral approach and the posterior approach, close to lateral pseudotumors—with a dissimilar appearance to bursal fluid collections by virtue of thick irregular walls and mixed internal signal intensity—surrounding the greater trochanter and stripping the abductor muscle tendons from their insertion ( and ).

Half of our patients’ hips had a pseudotumor on MRI examination. Pseudotumors are well described in patients with MOM hip implants. The reported prevalence in both symptomatic and asymptomatic patients ranges from 0.1% to 69% (CitationPandit et al. 2008, Canadian Hip Resurfacing Study 2011, CitationSabah et al. 2011, CitationChang et al. 2012, CitationHart et al. 2012).

We found progression of pseudotumor grade. In addition, 5 cases developed new pseudotumors, at a median time point of 59 months post-implantation.

Revision of MOM hip implants with soft-tissue pathology is associated with poor outcomes, and there is growing evidence to support early revision to a non-MOM hip implant to prevent irreversible damage (CitationDaniel et al. 2012). CitationCampbell et al. (2008) observed that patients can expect a good outcome if their soft tissue remains intact. CitationGrammatopolous et al. (2009) reported poor outcomes in patients following revision of a MOM hip replacement due to pseudotumor, with a high rate of complications. CitationLiddle et al. (2013) highlighted the degree of misdiagnosis possible when planning for revision of MOM hip implants. They stated that preoperative imaging can underestimate the degree of soft-tissue abnormalities seen at revision surgery, including a high rate of severe abductor muscle atrophy and stripping of the tendinous attachment. If progressive and destructive change in soft tissue is possible, prediction of those patients who are likely to fail is paramount so that revision can be undertaken early to ensure a better outcome.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to use serial MRI imaging to assess the longitudinal changes in muscle atrophy associated with large-diameter MOM hip implants. Recent studies concentrating on the natural history of soft-tissue pathology have focused on pseudotumors, and since most authors have used the Anderson classification (CitationAnderson et al. 2011) when grading MRI findings, it is difficult to quantify the effect on muscles and other soft-tissue abnormalities individually.

CitationAlmousa et al. (2013) used serial ultrasound assessments (2 years apart), and demonstrated variation in the size of pseudotumors—especially after revision surgery. Ebreo et al. (2013) used serial MRI to classify soft-tissue changes in 80 patients with 28-mm MOM Ultima hips. 6 hips with normal scans developed disease after sequential scanning, and overall, 15 hips showed progression on serial imaging. We are not sure if these findings can be generalized to large diameter (LD, > 36 mm) MOM hips, since the mode of failure of the Ultima stem includes macroscopic corrosion of the stem-cement interface (CitationDonell et al. 2010), which is not seen with other LD MOM hips. Van der Weegen et al. (2013) reported serial MRI findings in 37 hips with change in only 2 cases, including a new pseudotumor that developed 4 years after implantation.

36 of the 41 pseudotumors identified in our study were present at the time of the first MRI, median 65 months after surgery. This is similar to the results of other studies, which suggests that most pseudotumors arise within 5 years of implantation (Ebreo et al. 2013, van der Weegen et al. 2013) and reach a steady state.

Conclusion

Muscle atrophy after MOM hip arthroplasty is a common finding. This is the first study involving serial MRI of large-diameter MOM hips to investigate hip muscle scores. In 6 of 74 hips studied, we found that atrophy of the posterior third of the gluteus medius progressed between scans with a mean interval of 11 months. Assessment of the muscles on MRI is important in the monitoring of these patients, in order to help identify those who are at risk of developing abductor dysfunction and poor clinical outcome. An interval of 12 months would be reasonable, based on our observations. MRI findings are likely to precede clinical symptoms and support repeat MRI in the follow-up of a MOM hip.

Supplementary data

Table 1 and Tables 3–6 are available at Acta’s website (www.actaorthop.org), identification number 7564.

Supplementary Material

Download PDF (37.7 KB)Study design: RB, JH, JM, RC, JS, and AH. Collection of data: RB, MK, JM, RC, JS, and AH. Radiological analysis: RB and MK. Statistical analysis: RB and EC. Manuscript preparation: RB, MK, EC, JH, JM, RC, JS, and AH.

We thank Gwynneth Lloyd, Avril Power, and Pamela Coward who helped coordinate data collection for this study.

All the authors certify that that they have no commercial associations (e.g. consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements etc.) that might constitute conflicting interests in connection with the paper.

- Almousa SA , Greidanus NV , Masri BA , Duncan CP , Garbuz DS . The natural history of inflammatory pseudotumors in asymptomatic patients after metal-on-metal hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2013; 471(12): 3814-21.

- Anderson H , Toms AP , Cahir JG , Goodwin RW , Wimhurst J , Nolan JF . Grading the severity of soft tissue changes associated with metal-on-metal hip replacements: reliability of an MR grading system. Skeletal Radiol 2011; 40(3): 303-7.

- Bryant D , Havey TC , Roberts R , Guyatt G . How many patients? How many limbs? Analysis of patients or limbs in the orthopaedic literature: a systematic review. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2006; 88(1): 41-5.

- Campbell P , Shimmin A , Walter L , Solomon M . Metal sensitivity as a cause of groin pain in metal-on-metal hip resurfacing. J Arthroplasty 2008; 23(7): 1080-5.

- Canadian Hip Resurfacing Study . A survey on the prevalence of pseudotumors with metal-on-metal hip resurfacing in Canadian academic centers. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2011; 93 Suppl 2: 118-21.

- Chang EY , McAnally JL , Van Horne JR , Statum S , Wolfson T , Gamst A , Chung CB . Metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty: do symptoms correlate with MR imaging findings? Radiology 2012; 265(3): 848-57.

- Daniel J , Holland J , Quigley L , Sprague S , Bhandari M . Pseudotumors associated with total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2012; 94(1): 86-93.

- Donell ST , Darrah C , Nolan JF , Wimhurst J , Toms A , Barker TH , Case CP , Tucker JK , Norwich Metal-on-Metal Study. Early failure of the Ultima metal-on-metal total hip replacement in the presence of normal plain radiographs. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2010; 92(11): 1501-8.

- Drexler M , Dwyer T , Kosashvili Y , Chakravertty R , Abolghasemian M , Gollish J . Acetabular cup revision combined with tensor facia lata reconstruction for management of massive abductor avulsion after failed total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2014; 29(5): 1052-7.

- Ebreo D , Bell PJ , Arshad H , Donell ST , Toms A , Nolan JF . Serial magnetic resonance imaging of metal-on-metal total hip replacements. Follow-up of a cohort of 28 mm Ultima TPS THRs. Bone Joint J 2013; 95-B(8): 1035-9.

- Fang CS , Harvie P , Gibbons CL , Whitwell D , Athanasou NA , Ostlere S . The imaging spectrum of peri-articular inflammatory masses following metal-on-metal hip resurfacing. Skeletal Radiol 2008; 37(8): 715-22.

- Grammatopolous G , Pandit H , Kwon YM , Gundle R , McLardy-Smith P , Beard DJ , Murray DW , Gill HS . Hip resurfacings revised for inflammatory pseudotumour have a poor outcome. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2009; 91(8): 1019-24.

- Grimaldi A , Richardson C , Stanton W , Durbridge G , Donnelly W , Hides J . The association between degenerative hip joint pathology and size of the gluteus medius, gluteus minimus and piriformis muscles. Man Ther 2009; 14(6): 605-10.

- Hart A . [MRI investigations in patients with problems due to metal-on-metal implants]. Orthopade 2013; 42(8): 629-36.

- Hart AJ , Satchithananda K , Liddle AD , Sabah SA , McRobbie D , Henckel J , Cobb JP , Skinner JA , Mitchell AW . Pseudotumors in association with well-functioning metal-on-metal hip prostheses: a case-control study using three-dimensional computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2012; 94(4): 317-25.

- Hayter CL , Gold SL , Koff MF , Perino G , Nawabi DH , Miller TT , Potter HG . MRI findings in painful metal-on-metal hip arthroplasty. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2012; 199(4): 884-93.

- Landis JR , Koch GG . The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977; 33(1): 159-74.

- Liddle AD , Satchithananda K , Henckel J , Sabah SA , Vipulendran KV , Lewis A , Skinner JA , Mitchell AW , Hart AJ . Revision of metal-on-metal hip arthroplasty in a tertiary center: a prospective study of 39 hips with between 1 and 4 years of follow-up. Acta Orthop 2013; 84(3): 237-45.

- Madsen MS , Ritter MA , Morris HH , Meding JB , Berend ME , Faris PM , Vardaxis VG . The effect of total hip arthroplasty surgical approach on gait. J Orthop Res 2004; 22(1): 44-50.

- Nawabi DH , Gold S , Lyman S , Fields K , Padgett DE , Potter HG . MRI predicts ALVAL and tissue damage in metal-on-metal hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2014; 472(2): 471-81.

- Pandit H , Glyn-Jones S , McLardy-Smith P , Gundle R , Whitwell D , Gibbons CL , Ostlere S , Athanasou N , Gill HS , Murray DW . Pseudotumours associated with metal-on-metal hip resurfacings. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2008; 90(7): 847-51.

- Pfirrmann CW , Notzli HP , Dora C , Hodler J , Zanetti M . Abductor tendons and muscles assessed at MR imaging after total hip arthroplasty in asymptomatic and symptomatic patients. Radiology 2005; 235(3): 969-76.

- Sabah SA , Mitchell AW , Henckel J , Sandison A , Skinner JA , Hart AJ . Magnetic resonance imaging findings in painful metal-on-metal hips: a prospective study. J Arthroplasty 2011; 26(1): 71-6, 6 e1-2.

- Toms AP , Marshall TJ , Cahir J , Darrah C , Nolan J , Donell ST , Barker T , Tucker JK . MRI of early symptomatic metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty: a retrospective review of radiological findings in 20 hips. Clin Radiol 2008; 63(1): 49-58.

- van der Weegen W , Brakel K , Horn RJ , Hoekstra HJ , Sijbesma T , Pilot P , Nelissen RG . Asymptomatic pseudotumours after metal-on-metal hip resurfacing show little change within one year. Bone Joint J 2013; 95-B(12): 1626-31.