Abstract

Background and purpose — Dislocation is one of the most common complications following hip arthroplasty. Delay until reduction leads to pain for the patient, and may increase the risk of complications. We investigated the safety aspect of a fast-track pathway for dislocated hip arthroplasties and evaluated its effect on surgical delay and length of stay (LOS).

Patients and methods — 402 consecutive and unselected dislocations (253 patients) were admitted at our institution between May 10, 2010 and September 31, 2013. The fast-track pathway for early reduction was introduced on January 9, 2011. Fast-track patients with a suspected dislocation (with no radiographic verification) were moved directly to the post-anesthesia care unit and then straight to the operating room. Dislocation was confirmed under fluoroscopy with reduction under general anesthesia. Surgical delay (in hours), LOS (in hours), perioperative complications, and complications during the hospital stay were recorded. Dislocation status for fast-track patients (confirmed or unconfirmed by fluoroscopy) was also recorded.

Results — Both surgical delay (2.5 h vs. 4.1 h; p < 0.001) and LOS (26 h vs. 31 h; p < 0.05) were less in patients admitted through the fast-track pathway than in patients on regular pathway. Perioperative complications (1.6% vs. 3.7%) and complications during the hospital stay (11% vs. 15%) were also less, but not statistically significantly so. Only 1 patient admitted through fast-track pathway had a fracture instead of a dislocation; all the other fast-track patients with suspected dislocation actually had dislocations.

Interpretation — The fast-track pathway for reduction of dislocated hip arthroplasty results in less surgical delay and in reduced LOS, without increasing perioperative complications or complications during the patient’s stay.

Dislocation is one of the most common complications following hip arthroplasty, with reported incidences ranging from less than 1% to over 15%, and with higher rates reported after revision arthroplasty and arthroplasty performed for proximal femoral fracture (Phillips et al. 2003, CitationKhatod et al. 2006, CitationPatel et al. 2007). Delay before reduction prolongs pain and discomfort, and may result in sciatic palsy due to traction or hematoma. Reduction as soon as possible after diagnosis is therefore recommended (CitationZahar et al. 2013).

In recent years, much attention has been paid to optimizing logistics in elective (Husted et al. 2012) and acute orthopedic surgery (CitationPedersen et al. 2008, CitationPalm et al. 2012). In particular, reduced surgical delay for hip fracture patients has been a priority, as it reduces the mortality risk (CitationShiga et al. 2008, CitationDaugaard et al. 2012). While surgical delay has been investigated for other groups of fracture patients (CitationStreubel et al. 2011, CitationMenendez and Ring 2014), there have not been any similar investigations regarding reduction in surgical delay for dislocated arthroplasties, except comparing reduction at the emergency department to admission and reduction in theater (CitationFrymann et al. 2005, CitationGagg et al. 2009, CitationLawrey et al. 2012).

We investigated whether a fast-track approach to dislocated hip arthroplasty and hemiarthroplasty (1) reduces surgical delay, (2) reduces length of stay, and (3) is safe regarding in-hospital and perioperative complications.

Patients and methods

We identified 479 consecutive, unselected patients who were scheduled to undergo a reduction of a dislocated hip arthroplasty at our institution between May 10, 2010 and September 31, 2013. All types of hip arthroplasties, including total hip arthroplasty (THA) and hemiarthroplasty, were included. 35 cases were missing some or all of the relevant data, while 42 cases occurred while the patient was already admitted to the hospital, thus leaving 402 patients for analysis. More female patients (71%) than male patients (29%) with dislocations were admitted. Mean age was 75 years. 90% of the patients had a THA, while 10% had a hemiarthroplasty ().

Table 1. Demographics

Patients admitted through the standard pathway were examined by a doctor in the emergency room (ER) and then transported to the radiology department for examination if dislocation was suspected. If dislocation was radiographically confirmed, the patient was admitted to the hospital, transferred to the orthopedic ward, and prepared for surgery. The dislocation was reduced in the OR (operating room) under general anesthesia (GA).

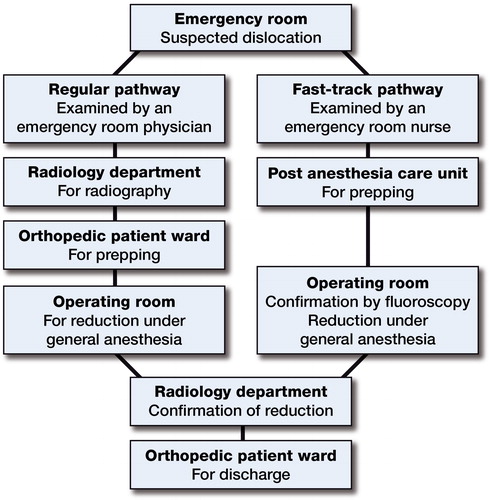

The fast-track pathway for early reduction was introduced on January 9, 2011. Fast-track patients with clinically suspected dislocation (shortening and internal or external rotation of the hip, and no history of falling or direct trauma) were examined by a nurse in the ER and moved directly to the post-anesthesia care unit (PACU) and then straight to the OR, bypassing radiographic examination. Dislocation was confirmed under fluoroscopy in the OR and reduction took place under GA. All the patients (both in the fast-track pathway and the regular pathway) were transferred to the radiology department for confirmation of reduction, and then to the orthopedic ward for mobilization and discharge ().

Figure 1. The regular pathway and fast-track pathway for reduction of a suspected dislocated hip arhtroplasty.

The following parameters were recorded: surgical delay (hours from admission in the ER until reduction), LOS (hours from admission in the ER until discharge), intraoperative complications (fracture, failed dislocation, other) and in-hospital complications (cardiac, pulmonary, thromboembolic, nerve damage, re-dislocation, other) from patient charts. Dislocation status for fast-track patients (confirmed or unconfirmed by fluoroscopy) was recorded from surgical charts. Only time until the first reduction attempt (whether successful or unsuccessful) was used in our analysis of surgical delay.

Statistics

Mean values with standard deviation (SD) are given for normally distributed data, while median values with interquartile range (IQR) are given for non-normally distributed data. Mann-Whitney U-test was used to compare continuous non-parametric variables and chi-square test was used to compare categorical variables. SPSS version 21 was used for all statistical analyses.

Ethics Committee consent was not required for this trial.

Results

214 cases were admitted through the standard pathway and 188 cases were admitted through the fast-track pathway. Cases admitted through the standard and fast-track pathways were comparable regarding age, sex, ASA score, type of arthroplasty, and type of reduction.

80% of the patients who were scheduled for reduction of a dislocated hip arthroplasty (214 of 269) were admitted through the fast-track pathway after its introduction on January 9, 2011. Surgical delay was reduced by 1.6 h and LOS was reduced by 4.6 h (). Intraoperative complications occurred in 3.7% of cases admitted through the standard pathway and in 1.6% of cases admitted through the fast-track pathway (). Of the 8 failed reductions in the standard pathway cohort, 7 cases were reduced open and 1 case had a successful closed reduction on the following day.

Table 2. Length of stay and surgical delay for all patients. Values are median (IQR)

Table 3. Complications as identified in patient records. Values are number (percentage)

In-hospital complications occurred in 15% and 11% of cases admitted through standard and fast-track pathways, respectively (). 1 of the 188 cases received through the fast-track pathway had a fracture and no dislocation; the rest of the cases had dislocations.

Discussion

In this retrospective, comparative cohort study, we found that the fast-track pathway for reduction of dislocated hip arthroplasty resulted in less surgical delay and reduced LOS compared to the standard pathway, without increasing intraoperative or in-hospital complications.

Several studies have found that increased surgical delay for hip fractures is associated with increased mortality (CitationShiga et al. 2008, CitationDaugaard et al. 2012), while others have not (CitationHolt et al. 2008, CitationVerbeek et al. 2008, CitationLund et al. 2014). This has resulted in several national guidelines recommending early surgery (NICE guidelines 2011, CitationMak et al. 2010). To our knowledge, there have been no studies investigating the effect of surgical delay on mortality and morbidity for patients with dislocated arthroplasty. Even so, early reduction is recommended, to minimize the risk of neurological and vascular complications—and also pain and discomfort for the patient (CitationZahar et al. 2013). Several authors have therefore proposed immediate reduction in the ER under sedation (CitationFrymann et al. 2005, CitationGagg et al. 2009, CitationLawrey et al. 2012). However, sedation in the ER can lead to “oversedation” and airway obstruction, and has a lower success rate than reduction under general anesthesia in the OR (CitationFrymann et al. 2005; Dela CitationCruz et al. 2014). In the present study, we found a mean surgical delay of 2.5 h for fast-track cases, which is comparable to surgical delay times achieved for hip arthroplasty reduction in the ER reported by several authors (CitationFrymann et al. 2005; CitationGagg et al. 2009; CitationLawrey et al. 2012). Surgical delay for both the fast-track pathway cases and the regular pathway cases in our study was shorter than what has been reported previously for surgical delay until reduction in the OR (CitationFrymann et al. 2005, CitationWan et al. 2008, CitationGagg et al. 2009). We believe that the fast-track setup with reduction under general anesthesia in OR provides optimal conditions for reduction, as it allows airway control, relaxation to aid in reduction, and the possibility of open reduction if such is required.

The fast-track concept was initially introduced for elective surgery, and it is currently widely used in knee and hip arthroplasty (CitationHusted 2012). Several studies have shown that it reduces LOS without leading to increased rates of complication, mortality, or morbidity, while increasing patient satisfaction (CitationHusted et al. 2008, 2012). Similar results have been reported by CitationPedersen et al. (2008), who showed an optimized program for hip fracture patients to reduce both LOS and in-hospital complications postoperatively. Few studies have investigated LOS following a dislocated hip arthroplasty (CitationLawrey et al. 2012, CitationFrymann et al. 2005). This is possibly due to the large variation in logistic setup between different institutions: some dislocations are reduced in the ER, while others are admitted to the hospital and reduced in the OR under general anesthesia. The LOS following the fast-track pathway for reduction of a dislocated hip arthroplasty reported in our study was shorter than the LOS reported by CitationLawrey et al. (2012) for patients reduced in the OR, and it was similar to the LOS for dislocations reduced by orthopedic service doctors in the ER.

One study found that there were substantial financial costs associated with dislocation of hip arthroplasties, with most of the costs being due to the hospital stay and nursing (CitationSanchez-Sotelo et al. 2006). Hence, further economic analysis might reveal possible financial benefits of the fast-track pathway for reduction of dislocated hip arthroplasties in departments that traditionally reduce dislocated arthroplasty in the OR.

It is important to emphasize that a fast-track pathway for reduction of a dislocated arthroplasty is a concept involving optimized logistics, rather than being a single treatment method. Minimization of LOS is not a primary goal in itself, but rather a positive consequence of optimized logistics and patient treatment. Safety aspects of such pathways must always be evaluated, and patient safety given high priority. The rates of successful closed reduction in the present study were high; they were comparable to OR reduction rates reported by CitationLawrey et al. (2012), higher than ER reduction rates reported by CitationLawrey et al. (2012), and higher than reduction rates reported by CitationGagg et al. (2009). We found that in-hospital complication rates were similar in cases admitted through both pathways, suggesting that early reduction does not increase the rate of in-hospital complications.

Patients received through the fast-track pathway bypass the radiology department, thus allowing the possibility of a hip fracture being clinically mistaken for a dislocation. To minimize any potentially negative consequences, dislocations are confirmed under fluoroscopy in the OR before general anesthesia. If a fracture is present, the patient is prepared for fracture surgery, which is then performed as soon as logistics allow. In our study, only 1 out of 188 fast-track dislocations had a fracture instead of a dislocation. The remainder all had dislocations, suggesting that the criteria for entering the fast-track pathway are sufficiently precise.

The main weakness of the present study was the retrospective design: some intraoperative and in-hospital complications could possibly have been neglected in the patient records. The main changes in the fast-track pathway compared to the regular pathway in our study was replacement of radiographic examination in the radiology department with fluoroscopy in the OR and preparation of the patient in the post-anesthesia care unit rather than in the orthopedic patient ward. Thus, the fast-track approach that we describe may not be applicable to all other departments, especially those where reduction of dislocated hip arthroplasty takes place in the ER. We did not investigate mortality rates or re-admission rates. However, as this was an unselected and consecutive patient cohort, and treatment following reduction was identical for both fast-track and standard pathways, it is unlikely that re-admission rates would have been affected for cases admitted through the fast-track pathway.

In summary, a fast-track pathway for reduction of dislocated hip arthroplasties results in less surgical delay and reduced LOS without any increase in intraoperative or in-hospital complications. Future studies, preferably large prospective cohort studies, should include data on mortality, re-admissions, and patient satisfaction.

KG, AT, and HH wrote the protocol; all the authors revised it; KG and FW undertook all gathering of data; KG, HP, AT, and HH performed and evaluated all the statistical analyses. KG wrote the first draft of the manuscript; HH revised it; all the authors revised the draft and approved the final version. All the authors had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analyses.

No competing interests declared.

- Dela Cruz JE, Sullivan DN, Varboncouer E, Milbrandt JC, Duong M, Burdette S, et al. Comparison of procedural sedation for the reduction of dislocated total hip arthroplasty. West J Emerg Med 2014; 15(1): 76–80.

- Daugaard CL, Jørgensen HL, Riis T, Lauritzen JB, Duus BR, van der Mark S. Is mortality after hip fracture associated with surgical delay or admission during weekends and public holidays? A retrospective study of 38,020 patients. Acta Orthop 2012; 83(6): 609–13.

- Frymann SJ, Cumberbatch G LA, Stearman A SL. Reduction of dislocated hip prosthesis in the emergency department using conscious sedation: a prospective study. Emerg Med J 2005; 22(11): 807–9.

- Gagg J, Jones L, Shingler G, Bothma N, Simpkins H, Gill S, et al. Door to relocation time for dislocated hip prosthesis: multicentre comparison of emergency department procedural sedation versus theatre-based general anaesthesia. Emerg Med J 2009; 26(1): 39–40.

- Holt G, Smith R, Duncan K, Finlayson DF, Gregori A. Early mortality after surgical fixation of hip fractures in the elderly: an analysis of data from the scottish hip fracture audit. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2008; 90(10): 1357–63.

- Husted H. Fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty: clinical and organizational aspects. Acta Orthop 2012; 83(Suppl 346):1–39.

- Husted H, Holm G, Jacobsen S. Predictors of length of stay and patient satisfaction after hip and knee replacement surgery: fast-track experience in 712 patients. Acta Orthop 2008; 79(2): 168–73.

- Khatod M, Barber T, Paxton E, Namba R, Fithian D. An analysis of the risk of hip dislocation with a contemporary total joint registry. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2006; 447: 19–23.

- Lawrey E, Jones P, Mitchell R. Prosthetic hip dislocations: is relocation in the emergency department by emergency medicine staff better? Emerg Med Australas 2012; 24(2): 166–74.

- Lund CA, Møller AM, Wetterslev J, Lundstrøm LH. Organizational factors and long-term mortality after hip fracture surgery. A cohort study of 6143 consecutive patients undergoing hip fracture surgery. PLoS One 2014; 9(6): e99308.

- Mak J CS, Cameron ID, March LM. Evidence-based guidelines for the management of hip fractures in older persons: an update. Med J Aust 2010; 192(1): 37–41.

- Menendez ME, Ring D. Does the timing of surgery for proximal humeral fracture affect inpatient outcomes? J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2014; 23(9): 1257-62.

- NICE guidelines on osteoarthritis [Internet]. Available from: http://publications.nice.org.uk/osteoarthritis-cg59

- Palm H, Krasheninnikoff M, Holck K, Lemser T, Foss NB, Jacobsen S, et al. A new algorithm for hip fracture surgery. Reoperation rate reduced from 18 % to 12 % in 2,000 consecutive patients followed for 1 year. Acta Orthop 2012; 83(1): 26–30.

- Patel PD, Potts A, Froimson MI. The dislocating hip arthroplasty: prevention and treatment. J Arthroplasty 2007; 22 (4 Suppl 1 ): 86–90.

- Pedersen SJ, Borgbjerg FM, Schousboe B, Pedersen BD, Jørgensen HL, Duus BR, et al. A comprehensive hip fracture program reduces complication rates and mortality. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008; 56(10): 1831–8.

- Phillips CB, Barrett JA, Losina E, Mahomed NN, Lingard EA, Guadagnoli E, et al. Incidence rates of dislocation, pulmonary embolism, and deep infection during the first six months after elective total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2003;85-A(1):20–6.

- Sanchez-Sotelo J, Haidukewych GJ, Boberg CJ. Hospital cost of dislocation after primary total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2006; 88(2): 290–4.

- Shiga T, Wajima Z, Ohe Y. Is operative delay associated with increased mortality of hip fracture patients? Systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Can J Anaesth 2008; 55(3): 146–54.

- Streubel PN, Ricci WM, Wong A, Gardner MJ. Mortality after distal femur fractures in elderly patients. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2011; 469(4): 1188–96.

- Verbeek D OF, Ponsen KJ, Goslings JC, Heetveld MJ. Effect of surgical delay on outcome in hip fracture patients: a retrospective multivariate analysis of 192 patients. Int Orthop 2008; 32(1): 13–8.

- Wan Z, Boutary M, Dorr LD. The influence of acetabular component position on wear in total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2008; 23(1): 51–6.

- Zahar A, Rastogi A, Kendoff D. Dislocation after total hip arthroplasty. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 2013; 6(4): 350–6.