Abstract

Background and purpose — Shoulder impingement syndrome is common, but treatment is controversial. Arthroscopic acromioplasty is popular even though its efficacy is unknown. In this study, we analyzed stage-II shoulder impingement patients in subgroups to identify those who would benefit from the operation.

Patients and methods — In a previous randomized study, 140 patients were either treated with a supervised exercise program or with arthroscopic acromioplasty followed by a similar exercise program. The patients were followed up at 2 and 5 years after randomization. Self-reported pain was used as the primary outcome measure.

Results — Both treatment groups had less pain at 2 and 5 years, and this was similar in both groups. Duration of symptoms, marital status (single), long periods of sick leave, and lack of professional education appeared to increase the risk of persistent pain despite the treatment. Patients with impingement with radiological acromioclavicular (AC) joint degeneration also had more pain. The patients in the exercise group who later wanted operative treatment and had it did not get better after the operation.

Interpretation — The natural course probably plays a substantial role in the outcome. Based on our findings, it is difficult to recommend arthroscopic acromioplasty for any specific subgroup. Regarding operative treatment, however, a concomitant AC joint resection might be recommended if there are signs of AC joint degeneration. Even more challenging for the development of a treatment algorithm is the finding that patients who do not recover after nonoperative treatment should not be operated either.

Shoulder impingement syndrome has traditionally been divided into 3 progressive stages: (1) edema and hemorrhage (stage I), (2) fibrosis and tendinitis (stage II), and (3) tears of the rotator cuff, biceps ruptures, and bone changes (stage III) (CitationNeer 1983). Nowadays, the term impingement syndrome is used to refer to a full range of rotator cuff abnormalities, being still a diagnosis based on physical examination (CitationPapadonikolakis et al. 2011). CitationDiercks et al. (2014) highlighted the need for a combination of clinical tests in the diagnosis, and suggested the use of an imaging test after prolonged symptoms (of more than 6 weeks) to rule out rotator cuff tears. Shoulder impingement is a common cause of shoulder pain (van der CitationWindt et al. 1995, CitationUrwin et al. 1998). Tendinopathy is considered to have a multifarious etiology: intrinsic mechanisms may be more important than extrinsic mechanisms (CitationFactor and Dale 2014).

Both nonoperative treatment and operative treatment have been used to treat this syndrome (Coghlan et al. 2008, CitationDorrestijn et al. 2009, CitationKromer et al. 2009, CitationChaudhury et al. 2010). It has been shown that arthroscopic acromioplasty is not superior to a supervised exercise program (CitationKetola et al. 2009, 2013, CitationPapadonikolakis et al. 2011, CitationDiercks et al. 2014, CitationSaltychev et al. 2015). However, arthroscopic acromioplasty has been increasingly used during the last decade (CitationPaloneva et al. 2015). Similar results have been obtained with open and arthroscopic acromioplasty (CitationDavis et al. 2010). It is unclear whether a specific subgroup of patients who would benefit from arthroscopic acromioplasty can be identified. In most studies, the inclusion criterion has simply been failure of nonoperative treatment (CitationBrox et al. 1999, CitationHenkus et al. 2009). We have already done a cost-effectiveness study that suggested that arthroscopic acromioplasty followed by a structural exercise program is less cost-effective than exercise treatment alone (CitationKetola et al. 2009), and this was confirmed by CitationSaltychev et al. (2015). We have now analyzed the 140 impingement patients from our previous study (CitationKetola et al. 2009) in subgroups to find out whether there is a subgroup of patients who would really benefit from arthroscopic acromioplasty. Secondly, we wanted to determine whether there is a subgroup in which the procedure should be avoided.

Patients and methods

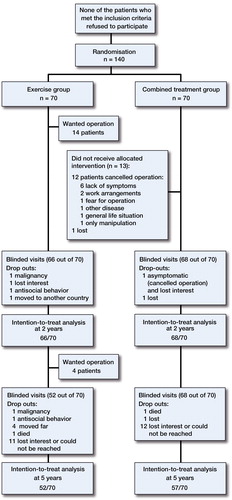

The original study design was a controlled randomized trial. 140 patients (18–60 years old) were included in the study if history and clinical tests indicated impingement syndrome (52 men and 88 women, mean age 47 years). All patients were collected from the Kanta-Häme Health Care District in Finland, which at the time of the inclusion had a population of 165,000. The study started in June 2001, and by the end of July 2004 we had recruited 140 patients—as planned from a power calculation. The dropout rate was 6 of 140 at 2 years and 31 of 140 at 5 years. It was therefore possible to analyze 134 of the 140 randomized patients at 2 years and 109 of the 140 at 5 years (). MRI of the shoulder was performed before randomization, as a supplementary tool to exclude other shoulder pathologies such as full-thickness rotator cuff lesions. All the radiographs were evaluated by 2 independent radiologists and their consensus values were used in the analyses. For inclusion, the symptoms had to be resistant to previous attempts to treat them nonoperatively during the previous 3 months. None of the patients had had previous shoulder surgery. The inclusion and exclusion criteria and the precise study protocol are described in the report of the 2-year results (CitationKetola et al. 2009).

The 2 treatment groups were (1) arthroscopic acromioplasty followed by a supervised and structured exercise treatment program (the combined treatment group), and (2) a similarly supervised and structured exercise treatment program alone without any surgery (the exercise treatment group). The only difference between treatments in these 2 study groups was the operation. For those patients who were randomized to the combined treatment group, an arthroscopic decompression was first performed. All the operations were performed under regional anesthesia by the same experienced orthopedic surgeon. After the diagnostic part of the procedure, debridement and decompression were done by shaver and/or vaporizer. If the coracoacromial ligament felt tight or thick, it was released. Acromioplasty was then performed with a burr drill. After that, these patients were also given a similar schedule of physiotherapy and training sessions.

The main follow-up points were at 2 and 5 years after randomization. A physiotherapist, who was blind regarding which patients were in the treatment group, performed all the assessments (with the patients in T-shirts) and was not otherwise involved in the study, treatment, or rehabilitation.

Self-reported pain on a 0–10 visual analog scale (VAS) was used as the primary health outcome measure, and values at 2 and 5 years were also used in this ad hoc subgroup analysis. The proportion of pain-free patients was also used, with patients being considered free of pain if they reported pain at a level between 0 and 3 on VAS.

Secondary outcome measures were disability, working ability, pain at night (VAS values), shoulder disability questionnaire (SDQ) score, and reported painful days during the 3 months preceding the follow-up visit. For baseline characteristics used in this subgroup analysis, see Supplementary data, Table 1.

Statistics

Fisher’s exact test was used for the comparisons of proportions. Kruskal-Wallis test was used when VAS scales of the subgroups were compared. The association between patient characteristics and pain was tested using binary logistic regression analysis. Results are given as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Any p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 19.0.

Ethics

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the hospital district (Kanta-Häme Central Hospital; entry no. E9/2001, April 11, 2001).

Registration

The study has been registered at ClinicalTrials.gov, identifier NCT00349648.

Results

At 2 and 5 years, both groups reached statistically significantly better values in the outcome measures compared to baseline, which were simlar between the groups. These outcomes were calculated using the intention-to-treat (ITT) principle. Those who fully followed their study assignment were also analyzed separately using the per-protocol (PP) principle. Outcome was similar between the 2 treatment groups. However, the dissatisfied patients in the exercise group who eventually wanted and had an operation still had worse values after surgery than the others ().

Table 2. Results for the treatment groups at 5 years compared to those who were dissatisfied with conservative treatment and operated

Pain

At 5 years 82/109 of the patients were pain-free (self-reported pain less than 3 in the visual analog scale). Over 2 weeks long out of work periods due to shoulder reasons had occurred in 18/77 of the pain-free patients and in 12/27 of those patients who were painful at 5 years (p = 0.07). (Table 4, see Supplementary data).

The following factors had a statistically significant impact on pain (see Supplementary data, Tables 3 and 4).

Marital status. Living alone was associated with a higher risk of having pain at 2 years (OR = 3.3, CI: 1.4–7.8). When we divided the patients into those who experienced pain and those who were pain-free, those living alone appeared to have more pain at 2 years (p = 0.01) and at 5 years (p = 0.03).

Lack of professional education. At 2 years, the OR was 3.7 (CI: 1.2–11) for those with no education and 3.0 (CI: 0.93–9.5) for those who had gone through an occupational course.

Duration of symptoms prior to the randomization had a positive correlation with pain at 2 years, especially in those in the exercise group who later wanted an operation (p = 0.04). In the exercise group, 11/25 of the pain-free patients and 4/10 of the patients with pain had had symptoms over 1 year. In the combined treatment group, 12/25 of the pain-free patients and 9/13 of the patients with pain had had symptoms over 1 year. All of the 18 patients in the exercise group who wanted surgery had had symptoms over 1 year.

Long periods of sick leave was also associated with an increased risk of having pain. If a patient had been out of work before the randomization—for more than 2 weeks—for shoulder-related reasons, the risk of having pain was high at 2 years (OR = 2.5, CI: 1.1–5.8) and at 5 years (OR = 3.8, CI: 1.4–11).

Satisfaction at work. 5/7 of patients with a quite low or very low level of satisfaction experienced pain at 2 years. At 2 years, 72/80 of the pain-free patients were quite satisfied or very satisfied but only 28/41 of those with pain were quite satisfied or very satisfied. Only 2/80 of the pain-free patients had a quite low or very low level of satisfaction, whereas 5/41 of the patients with pain had a quite low or very low level of satisfaction (overall p = 0.01).

Requirements/challenges at work. In patients whose requirements/challenges at work were low or quite low, the fraction of pain-free subjects was 21/24. Of those who had heavy committments at work, more than half had pain at 5 years. Of the pain-free patients at 5 years, 10/80 reported having heavy committments at work, whereas in patients with pain the corresponding proportion was 11/27 (overall p = 0.01).

Loads lifted per workday. The highest risk (> 4-fold risk) of having pain at 2 years was in those who lifted a moderate amount during a workday, compared to those who lifted lighter or heavier loads. Of the patients who were pain-free, those who lifted light loads constituted 20/64 of the total. Of the patients with pain, those who lifted light loads accounted for 7/37 of the total (overall p = 0.02).

AC joint degeneration. In the combined treatment group, 21/22 of the pain-free patients had no or only mild AC joint degeneration at 5 years. In those with pain, 3/4 had moderate or severe degeneration of the AC joint (overall p = 0.01).

Discussion

Operative treatment is commonly used for shoulder impingement syndrome, even though its effectiveness has not been proven in the literature (CitationPapadonikolakis et al 2011, CitationDiercks et al 2014, CitationSaltychev et al. 2015). The fact that the diagnosis is merely clinical also makes comparison of different studies difficult. In a recent review and meta-analysis, the evidence on effectiveness of operative or nonoperative treatment was found to be limited (CitationSaltychev et al. 2015). This is in keeping with the Cochrane Collaboration report (Coghlan et al. 2008) and 2 previous reviews (CitationDorrestijn et al. 2009, CitationGebremariam et al. 2011).

Subgroup analyses are important if treatments with statistically similar outcomes show extensive heterogeneity of the treatment effect in individual patients (perhaps related to the diversity of the pathophysiology of the underlying disease). This may help to create more individualized indications and contraindications for the treatments of interest. Subgroup analyses must be predefined, carefully justified, and limited to a few clinically important questions (CitationRothwell 2005), because otherwise they could be misleading. We feel that the prospective nature of this carefully selected patient material justified a subgroup analysis.

In this study, we tried to determine whether the treatment works better in some subgroups than in others, acknowledging the risks of statistical problems and misinterpretations. In the subgroup analyses, we focused on differences from the average overall treatment effect and limited the questions to only a few clear and well-defined variables. Participation in intervention as intended, i.e. analysis according to the ITT principle or the PP principle, did not have any statistically significant effect on the results. Our study indicates that using self-reported pain (by VAS) or secondary outcome measures at 2 or 5 years for analysis, the effects of combined treatment did not differ significantly from the effects of treatment with supervised exercise alone. In this study we did not compare the overall effects of these 2 modes of treatment, but specifically analyzed the eventual additional value provided by the operation over and beyond the effect obtained using a structured and supervised exercise program alone (CitationKetola et al. 2009 and 2013).

Strengths and weaknesses

The dropout rate was small; it was possible to analyze 134 of the 140 randomized patients at 2 years and 109 of them at 5 years. The selection bias was low at the actual entry to the study, because at baseline all suitable subjects were willing to participate in the study. However, it is possible that some patients living in the hospital catchment area with similar pain-related complaints did not come to the hospital outpatient department, thus creating potential bias. The groups were similar at baseline. All arthroscopic acromioplasties were performed by one experienced surgeon who was considered to have reached the top of the learning curve, which contributed to the uniform quality of the operative care. Control visits/follow-up examinations were done by an independent and blinded physiotherapist who did not otherwise participate in the study. Due to multiple variables, the subgroup sizes became small, which would increase the risk of type-II error. In addition, there have been no reports and there is no common consensus on how shoulder impingement syndrome evolves over a long time. There may always be some patients who recover spontaneously and some others who are not cured despite the treatment given.

The natural course of the treated disease

The results at 2 and 5 years were similar between treatment groups and they seemed to continue to improve in a similar way in both groups after the first 2 years (to the 5-year follow-up). The effects of both procedures appeared to be long-lasting and to continue to improve over time (CitationKetola et al. 2013). Do these good results reflect the therapeutic intervention, or the natural long-term course of this syndrome?

The age limits for this study were 18 and 60 years. It has been shown that there are changes in acromial morphology with age. Both asymptomatic and symptomatic cuff tears increase with age (CitationYamamoto et al. 2010).

18 patients were not pleased with the results of the exercise treatment alone, and they were therefore operated later on. However, these patients did not do any better after the operation. We believe that there was a similar group of patients in the combined group as well, who would not respond to surgery either. So it appears that almost one-third of all patients with this diagnosis do not respond to any sort of treatment. The remaining two-thirds will get better irrespective of the nature of the treatment. It might well be that the natural course of the shoulder impingement syndrome contributes substantially to the improvement of those patients who are “healed” after treatment, during the 5-year follow-up.

It appears that patients who do not get better with nonoperative treatment do not get better with operative treatment either, although this may also partly depend on the duration of the symptoms before initiation of the treatment. This in any case challenges the previous guidelines of offering surgery to patients who “fail” with nonoperative treatment. Longer follow-up periods in patients with shoulder impingement syndrome are needed to learn more about the natural course of the disease.

Factors affecting the results of the treatment

A longer duration of symptoms appeared to be predictive of worse results in both groups. This probably reflects the possibility that impingement heals spontaneously if the condition has lasted less than 1 year. In this study, after this checkpoint the number of non-responders increased substantially. The same consideration probably explains the worse results in patients who had longer and more frequent periods of sick leave, which is in line with previous studies (Bot et al. 2005, CitationThomas et al. 2005, CitationReilingh et al. 2008).

There was a negative correlation between satisfaction at work and the perception of pain. The more demanding the work was, according to the patient’s own assessment, the worse was the prognosis for recovery. Similarly, lack of a higher education was associated with poor treatment results. Patients living alone had more pain, which might be explained by the lack of disease-related support. There are similar reports involving other orthopedic conditions where psychological factors have affected the perception of pain (CitationWahlman et al. 2014). Also, in shoulder complaints several psychological factors have been related to outcome (Bot et al. 2005). If the condition is refractory or the symptoms become bilateral, the overall prognosis is negatively affected. This is probably explained by the previously mentioned third of the patients who have a more difficult disease. This is the group that does not recover from the initial symptoms, which appears to happen to most of the patients who are treated more than 1 year after the onset of symptoms.

Only 1 radiological feature was significantly associated with pain perception after the treatment. If the patients had AC osteoarthritis, they had more pain than patients with normal AC joint radiology. The incidence of arthroscopic acromioplasty has been increasing, but has probably now reached a plateau (CitationVitale et al. 2010, Yu et al. 2010). Based on this material, we cannot justify the performance of this procedure to any single subgroup of impingement patients. However, if the patient is to be operated, a concomitant AC resection is only recommended if there are signs of AC joint degeneration.

Conclusions

There are no simple criteria to predict the natural course of the disease in patients suffering from shoulder impingement syndrome. This condition behaves somewhat differently from usual in some patient subgroups, which can be explained by the nature of the condition rather than the demographic properties of the patients. Regardless of the treatment chosen, most of the patients get better. If the patients do not recover by nonoperative means, it appears that they do not benefit from the operative treatment either.

Supplementary data

Tables 1, 3, and 4, are available at Acta’s website (www.actaorthop.org), identification number 8071.

IORT_A_1033309_SM1607.pdf

Download PDF (38.2 KB)All the authors participated in the conception and conduction of the study, and contributed to the final manuscript. SK, TR, MN, and IA: (overall) planning of the study (TR especially the physiotherapy aspects, IA especially the operative aspects). SK: substantial intellectual contribution. SK and TR: seeking permission from the ethical committee. SK, TR, MN, and IA: seeking permission from the hospitals. SK, JL, and MN, recruitment of the patients. SK, JL, and IA: organization of the study. SK: collection and organization of the data. SK and HH: statistics. JL, TR, and IA: clinical analysis of the data. SK and JL: literature review. SK and JL: writing of the draft. SK, JL, TR, MN, HH, and IA: critical commenting on and improvement of the manuscript.

No competing interests declared.

The late Professor of medicine Y. T. Konttinen from Helsinki University Central Hospital is gratefully acknowledged for his contribution to this shoulder study.

- Bot SD, van der Waal JM, Terwee CB, van der Windt DA, Scholten RJ, Bouter LM, et al. Predictors of outcome in neck and shoulder symptoms: a cohort study in general practice. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005; 30(16): E459–70.

- Brox JI, Gjengedal E, Uppheim G, Bohmer AS, Brevik JI, Ljunggren AE, et al. Arthroscopic surgery versus supervised exercises in patients with rotator cuff disease (stage II impingement syndrome): a prospective, randomized, controlled study in 125 patients with a 2 1/2-year follow-up. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 1999; 8(2): 102–11.

- Chaudhury S, Gwilym SE, Moser J, Carr AJ. Surgical options for patients with shoulder pain. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2010; 6(4): 217–26.

- Coghlan JA, Buchbinder R, Green S, Johnston RV, Bell SN. Surgery for rotator cuff disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008; (1): CD005619.

- Davis AD, Kakar S, Moros C, Kaye EK, Schepsis AA, Voloshin I. Arthroscopic versus open acromioplasty: a meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med 2010; 38(3): 613–8.

- Diercks R, Bron C, Dorrestijn O, Meskers C, Naber R, de Ruiter T, et al. Guideline for diagnosis and treatment of subacromial pain syndrome: a multidisciplinary review by the Dutch Orthopaedic Association. Acta Orthop 2014; 85(3): 314–22.

- Dorrestijn O, Stevens M, Winters JC, van der Meer K, Diercks RL. Conservative or surgical treatment for subacromial impingement syndrome? A systematic review. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2009; 18(4): 652–60.

- Factor D, Dale B. Current concepts of rotator cuff tendinopathy. Int J Sports Phys Ther 2014; 9(2): 274–88.

- Gebremariam L, Hay EM, Koes BW, Huisstede BM. Effectiveness of surgical and postsurgical interventions for the subacromial impingement syndrome: a systematic review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2011; 92(11): 1900–13.

- Henkus HE, de Witte PB, Nelissen RG, Brand R, van Arkel ER. Bursectomy compared with acromioplasty in the management of subacromial impingement syndrome: a prospective randomised study. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2009; 91(4): 504–10.

- Ketola S, Lehtinen J, Arnala I, Nissinen M, Westenius H, Sintonen H, et al. Does arthroscopic acromioplasty provide any additional value in the treatment of shoulder impingement syndrome?: a two-year randomised controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2009; 91(10): 1326–34.

- Ketola S, Lehtinen J, Rousi T, Nissinen M, Huhtala H, Konttinen YT, et al. No evidence of long-term benefits of arthroscopic acromioplasty in the treatment of shoulder impingement syndrome: Five-year results of a randomised controlled trial. Bone Joint Res 2013; 2(7): 132–9.

- Kromer TO, Tautenhahn UG, de Bie RA, Staal JB, Bastiaenen CH. Effects of physiotherapy in patients with shoulder impingement syndrome: a systematic review of the literature. J Rehabil Med 2009; 41(11): 870–80.

- Neer CS, 2nd. Impingement lesions. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1983; (173): 70–7.

- Papadonikolakis A, McKenna M, Warme W, Martin BI, Matsen FA3rd. Published evidence relevant to the diagnosis of impingement syndrome of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2011; 93(19): 1827–32.

- Paloneva J, Lepola V, Karppinen J, Ylinen J, Äärimaa V, Mattila VM. Declining incidence of acromioplasty in Finland. Acta Orthop 2015; 86 (2): 220–4.

- Reilingh ML, Kuijpers T, Tanja-Harfterkamp AM, van der Windt DA. Course and prognosis of shoulder symptoms in general practice. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008; 47(5): 724–730.

- Rothwell PM. Treating individuals 2. Subgroup analysis in randomised controlled trials: importance, indications, and interpretation. Lancet 2005; 365(9454): 176–86.

- Saltychev M, Aarimaa V, Virolainen P, Laimi K. Conservative treatment or surgery for shoulder impingement: systematic review and meta-analysis. Disabil Rehabil 2015; 37(1): 1–8.

- Thomas E, van der Windt DA, Hay EM, et al. Two pragmatic trials of treatment for shoulder disorders in primary care: generalisability, course, and prognostic indicators. Ann Rheum Dis 2005; 64(7): 1056–61.

- Urwin M, Symmons D, Allison T, Brammah T, Busby H, Roxby M, et al. Estimating the burden of musculoskeletal disorders in the community: the comparative prevalence of symptoms at different anatomical sites, and the relation to social deprivation. Ann Rheum Dis 1998; 57(11): 649–55.

- van der Windt DA, Koes BW, de Jong BA, Bouter LM. Shoulder disorders in general practice: incidence, patient characteristics, and management. Ann Rheum Dis 1995; 54(12): 959–64.

- Vitale MA, Arons RR, Hurwitz S, Ahmad CS, Levine WN. The rising incidence of acromioplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2010; 92(9): 1842–50.

- Wahlman M, Hakkinen A, Dekker J, Marttinen I, Vihtonen K, Neva MH. The prevalence of depressive symptoms before and after surgery and its association with disability in patients undergoing lumbar spinal fusion. Eur Spine J 2014; 23(1): 129–34.

- Yamamoto N, Muraki T, Sperling JW, Steinmann SP, Itoi E, Cofield RH, et al. Contact between the coracoacromial arch and the rotator cuff tendons in nonpathologic situations: A cadaveric study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2010; 19(5): 681–7.

- Yu E, Cil A, Harmsen WS, Schleck C, Sperling JW, Cofield RH. Arthroscopy and the dramatic increase in frequency of anterior acromioplasty from 1980 to 2005: an epidemiologic study. Arthroscopy 2010; 26(9 Suppl): S142–7.