Abstract

Background and purpose — Late prosthetic joint infections (PJIs) are a growing medical challenge as more and more joint replacements are being performed and the expected lifespan of patients is increasing. We analyzed the incidence rate of late PJI and its temporal trends in a nationwide population.

Patients and methods — 112,708 primary hip and knee replacements performed due to primary osteoarthritis (OA) between 1998 and 2009 were followed for a median time of 5 (1–13) years, using data from nationwide Finnish health registries. Late PJI was detected > 2 years postoperatively, and very late PJI was detected > 5 years postoperatively.

Results — During the follow-up, involving 619,299 prosthesis-years, 1,345 PJIs were registered: cumulative incidence 1.20% (95% CI: 1.13–1.26) (for knees, 1.41%; for hips, 0.92%). The incidence rate of late PJI was 0.069% per prosthesis-year (CI: 0.061–0.078), and it was greater after knee replacement than after hip replacement (0.080% vs. 0.057%, p = 0.006). The incidence rate of very late PJI was 0.051% per prosthesis-year (CI: 0.042–0.063), 0.058% for knees and 0.044% for hips (p = 0.2). The incidence rate of late PJI varied between 0.041% and 0.107% during the years of observation without any temporal trend (incidence rate ratio (IRR) = 0.98, 95% CI: 0.93–1.03). Very late PJI increased from 0.026% in 2004 to 0.056% in 2010 (IRR = 1.11, 95% CI: 1.02–1.20).

Interpretation — In our nationwide study, the incidence rate of late PJI after hip or knee arthroplasty was approximately 0.07% per prosthesis-year. The incidence of very late PJI appeared to increase.

The incidence, temporal trends, and risk factors for postoperative prosthetic joint infections (PJIs) after hip and knee replacements have been widely studied in various settings and with various study designs (CitationPhillips et al. 2006, CitationPulido et al. 2008, CitationJämsen et al. 2009a, CitationDale et al. 2012). In most studies, the follow-up time is 1–5 years.

Late PJIs (PJIs occurring more than 2 years after arthroplasty) are more rare than early and delayed postoperative PJIs, and they may occur many years after the joint replacement (CitationZimmerli et al. 2004, CitationSendi et al. 2011), making their epidemiology challenging to analyze. In some earlier single-center and multicenter studies as well as in studies based on Medicare data, the cumulative incidence of late PJI has been between 0.3% and 0.9% (CitationAinscow and Denham 1984, CitationMaderazo et al. 1988, CitationKaandorp et al. 1997, CitationCook et al. 2007, CitationOng et al. 2009, CitationKurtz et al. 2010, CitationTsaras et al. 2012). The sizes of study population, methods for identification of PJI, and follow-up times have varied.

As more and more joint replacements are performed annually (CitationNemes et al. 2014) and the expected lifespan of patients with joint replacements is increasing, the number of patients who are at risk of late PJI is growing. Also, the threshold for operating vulnerable patients with chronic diseases has become lower (CitationSingh and Lewallen 2014).

Because information on the incidence of late PJI is scarce, we analyzed the incidence of late PJI and its temporal trends in a nationwide primary hip and knee replacement population (due to primary osteoarthritis), with a cumulative follow-up time of 619,299 prosthesis-years. Patients of all age groups were included.

Material and methods

We selected primary hip and knee replacements performed due to primary osteoarthritis in Finland between January 1, 1998 and December 31, 2009. The operations were identified from the PERFECT database (http://www.thl.fi/en_US/web/en/project?id=21963) of the Finnish National Institute for Health and Welfare. The underlying methodology has been described elsewhere (CitationPeltola et al. 2011, CitationJämsen et al. 2013). The purpose of the database, created by combining records from several Finnish health registries, is to provide nationwide data about the outcomes of hip and knee replacements in Finnish citizens. It is known that the Finnish Arthroplasty Register alone does not detect all cases of PJI (CitationJämsen et al. 2009a, CitationHuotari et al. 2010).

In this study, we used records derived from the Finnish Arthroplasty Register and the Hospital Discharge Register. The Finnish Arthroplasty Register (FAR) has been collecting data on joint replacements since 1980, and since 1997 reporting to the register has been mandatory (CitationPuolakka et al. 2001). The Hospital Discharge Register (HDR) is based on mandatory discharge reports, and it covers all inpatient care (i.e. in both private and public hospitals). Since 1997, the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10), has been used for registering diagnoses and the Nordic Medico-Statistical Committee classification (NOMESCO) has been used for registering surgical procedures. In general, HDR is considered to be a reliable source of data (CitationSund 2012), the accuracy of orthopedic diagnoses being about 90% or higher (CitationSund et al. 2007, CitationMattila et al. 2008). Both registries include data on deaths, derived from Statistics Finland (Citationofficial statistics of Finland).

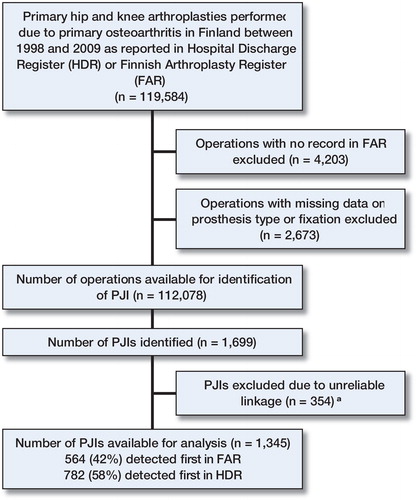

119,584 operations were identified in the FAR and the HDR. In order to obtain detailed operative data, we excluded 4,203 operations registered in the HDR but lacking corresponding records in the FAR, and 2,673 operations in which data on prosthesis type and fixation were lacking in the FAR. Hence, 112,708 operations were included in the analyses, representing 94% of the primary hip and knee replacements for osteoarthritis performed in Finland during the study period ().

Outcomes

In the FAR, revision joint replacements and resection arthroplasties (removal of a prosthesis) performed due to infection (according to the operating surgeon’s report) were considered to be PJIs. In the HDR, PJIs were identified by (1) a diagnosis code indicating PJI (T84.5), or (2) a diagnosis code indicating PJI (T84.5) or wound infection (T81.4), accompanied by a surgical procedure code indicating resection arthroplasty (NFU00, NGU00), revision joint replacement (NFC*, NGC*), arthrodesis (NGG30, NGG34), debridement (NFA*, NFF20, NFF25, NGA20, NGA30, NGF*), operation for infection (NFS*, NFW*, NGS*, NGW*), or amputation (NFQ20). The diagnosis code T81.4 combined with the selected operation codes was included because of the possibility of miscoding between T84.5 and T81.4. Two years after the primary operation, there are no superficial wound infections; when analyzing the late and very late PJIs, this should not cause any misclassification.

The PJIs identified were linked to the corresponding primary operations (based on Finnish citizens’ unique personal identification numbers) and operated joint (hip or knee, and laterality). As the operated side is routinely recorded in the FAR, PJIs identified from that registry (as well as corresponding records in the HDR) could be reliably linked. In the HDR, data concerning the affected side were missing for most PJIs. To link these events to primary operations, we used data concerning the patients’ other joint replacements (as registered in the FAR, from 1980 to 2010). Of the 1,699 PJIs identified in total, 354 (including 157 surgical procedures for the treatment of PJI and 197 hospitalizations with the diagnosis code T84.5) could not be reliably linked to the primary procedure and were excluded from the main analysis.

Prosthetic joints that were not infected were excluded from further follow-up (censored) according to the time of aseptic revision, the date of the patient’s death, or on December 31, 2010. All patients were followed up for at least 1 year unless death or revision occurred before that. The maximum follow-up time was 13 years.

PJIs were classified according to the time of presentation, as early (< 3 months after surgery), delayed (3–24 months after surgery), or late (> 24 months after surgery) (CitationZimmerli et al. 2004). Because postoperative PJIs caused by low-virulence bacteria, e.g. coagulase-negative staphylococci or Propionibacterium acnes, can sometimes be even more delayed than 2 years (CitationPortillo et al. 2013), we also analyzed very late PJIs (> 5 years after primary surgery) separately.

Statistics

The incidence of PJI was computed in 2 ways: (1) as the cumulative incidence of PJI throughout the follow-up time, and (2) as the incidence rate of PJIs per prosthesis-year. The incidence rates were calculated separately for each postoperative follow-up year. To account for deaths during each observation year and the effect of increasing annual operation numbers, we used the mid-year number of prostheses as the denominator when calculating the incidence rates. 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated by Wilson’s method (CitationAltman et al. 2000). Univariate analyses for categorical variables were calculated with the chi-squared test. Time trends in PJI incidence were tested with Poisson regression. The statistical significance of the temporal changes in treatment practices for late and very late PJIs (i.e. in the proportions of PJIs treated with or without removal or exchange of the prosthesis) were tested with ordinary least-squares regression. The data were analyzed with SPSS version 19.0 for Windows and Stata version 12.0.

Sensitivity analyses of cumulative incidences, incidence rates, and their time trends were performed to test how (1) exclusion of all simultaneous bilateral operations and (2) inclusion of the 354 PJIs whose linkage to joint replacement data was uncertain, would affect the results of the original analyses. To eliminate the possible influence of linkage problems, we also separately analyzed the 51,751 patients who had had only one joint operated between 1980 and 2011.

Ethics

The institutional review board of the National Institute for Health and Welfare gave permission for this study. The PERFECT project had previously been approved by the ethics committee of the same institution (THL 1406/6.02.00/2009).

Results

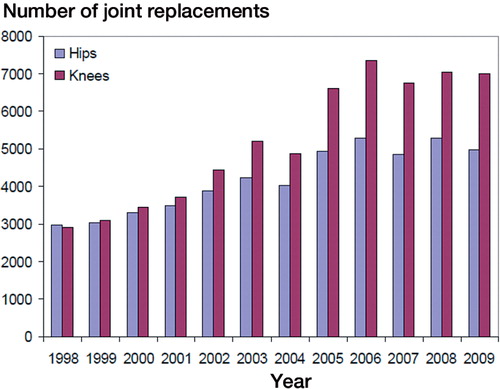

112,708 primary hip replacements (45%) and knee replacements (55%) due to primary osteoarthritis that were performed in Finland between 1998 and 2009 were included (92,626 patients). 4,731 operations (4.2%) were bilateral. The annual numbers of joint replacements increased ().

Figure 2. Numbers of primary hip and knee replacements due to primary osteoarthritis in Finland by year of operation.

The mean age of the patients at the time of the primary operation was 69 (21–102) years. 29% of the patients were under 65 years of age. 64% of the joint replacements were performed in females.

The median follow-up time was 5.0 (1–13) years. The total cumulative follow-up time was 619,299 prosthesis-years. Surveillance of the joint replacement ended because of patient death in 14,123 cases (13%) and because of aseptic revision in 3,023 cases (2.7%).

1,345 PJIs occurred (cumulative incidence = 1.20%, CI: 1.13–1.26). 630 (47%) of the PJIs were early (< 3 months after surgery), 435 (32%) were delayed (3–24 months after surgery), and 280 (21%) were late (> 2 years after surgery).

The late PJI incidence rate was 0.069% per prosthesis-year (280 of 405,653, CI: 0.061–0.078% per prosthesis-year) (Table 1, see Supplementary data). The incidence rate of very late PJIs (detected > 5 years postoperatively) was 0.051% per prosthesis-year (91 of 177,624, CI: 0.042–0.063% per prosthesis-year).

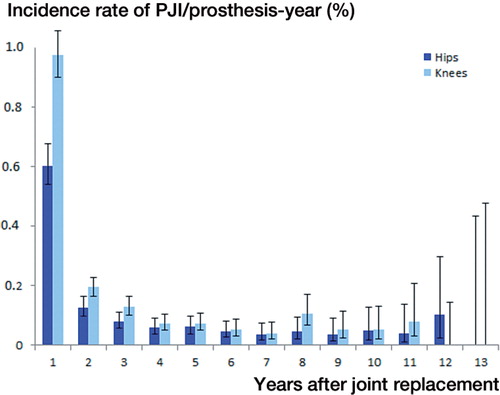

The cumulative incidence of PJI was greater after knee replacement (1.41%) than after hip replacement (0.92%), especially during the first 2 postoperative years (Table 2, see Supplementary data). Also, late PJIs occurred more frequently after knee replacement than after hip replacemen (), the incidence rates of late PJI being 0.080% (CI: 0.69–0.93) and 0.057% (CI: 0.45–0.69) per prosthesis-year (p = 0.006).

Figure 3. The incidence of PJI following hip and knee replacement per surveillance year. The error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

The incidence rate of late PJI varied between 0.041% and 0.11% per prosthesis-year over the years of observation (incidence rate ratio (IRR) = 0.98, CI: 0.93–1.03). Very late PJI increased from 0.026% per prosthesis-year in 2004 to 0.056% per prosthesis-year in 2010 (IRR = 1.11, CI: 1.02–1.20). The proportion of late PJIs treated with prosthesis removal or exchange declined from 5 out of 7 in 2000 to 21 out of 54 in 2010 (p = 0.003), and the proportion of very late PJIs declined from 2 out of 2 to 5 out of 26 (p < 0.001).

When the PJIs with uncertain linkage were also taken into account, the incidence of late and very late PJI increased to approximately 0.1% per prosthesis-year. The increase in the incidence of very late PJI remained statistically significant if simultaneous bilateral operations were excluded, but not if PJIs with uncertain linkage were included or if only 1 joint was operated (Table 3, see Supplementary data).

Discussion

In this nationwide analysis with more than 600,000 prosthesis-years surveyed, the incidence rate of late PJI in hip and knee prostheses was about 0.07% per prosthesis-year, and higher after knee replacements than after hip replacements. The annual risk of PJI stabilized after 3–5 years postoperatively to about 0.05% per year. During the study period, the incidence of very late PJI increased.

The strengths of this study were the large sample size and the truly nationwide study population with no exclusions by, for example, age or socioeconomic status. With comprehensive health register data, the follow-up was complete. Every prosthesis could be uniquely followed. The prosthesis was censored if revised for aseptic reasons, so postoperative PJIs from revision operations were not misclassified as late PJIs. In addition, with the exception of possible miscoding, most PJIs were probably registered—because PJIs are normally diagnosed and treated in hospital. With the use of HDR data, we could also identify PJIs treated without removal or prosthesis exchange, or even conservatively. This is important, as reoperations other than revision joint replacements are poorly captured by arthroplasty registers (CitationJämsen et al. 2009b, CitationHuotari et al. 2010).

A major limitation in our study was the restricted data content of the registry-based dataset. Information on microbiological findings, possible remote infections, or the sources of the bacteria were not available. Secondly, some PJIs may have been missed. This applies particularly to nonoperatively treated infections where the diagnosis code did not indicate the prosthesis joint involvement (e.g. in the setting of septicemia). Because of the increasing use of debridement and change of mobile parts with implant retention, the proportion of nonoperatively treated PJIs may have decreased during the study period, affecting the time trends in PJI. Even so, we believe that the cases coded as PJIs probably represented true case—and it is more likely that we missed some PJIs than that we had false-positive PJI cases. Thirdly, the linkage of the HDR data to joint replacement data led to certain problems in patients with several prosthetic joints. As we excluded these PJIs with linkage problems from the major analyses, the true incidence rates may actually have been higher than we have reported. However, despite the challenges with registry data, national registry-based studies like ours or international multicenter studies are needed to achieve sufficiently large study populations to examine time trends in the rare late and very late PJIs.

The overall cumulative PJI incidence of 1.2% (with a higher rate in knees than in hips) is in line with the results of other studies (CitationZimmerli et al. 2004, CitationPulido et al. 2008). When our incidences by each postoperative surveillance year (Table 2, see Supplementary data) are compared to US Medicare data (CitationOng et al. 2009, CitationKurtz et al. 2010) and Nordic arthroplasty registers (CitationDale et al. 2012), the time trend in the annual incidence of PJI was quite similar: the incidence is the highest during the first 2 postoperative years and then the annual risk of PJI stabilizes to a lower level.

The cumulative incidence of PJI detected later than 2 years from the operation in the Medicare data was 0.59% for hips (CitationOng et al. 2009) and 0.46% for knees (CitationKurtz et al. 2010). In another population-based study from Minnesota, USA, the figure was 0.7%, and—similar to our results—the incidence was higher for knees than for hips (CitationTsaras et al. 2012). In the 1980s, CitationMaderazo et al. (1988) estimated the cumulative incidence of late PJIs to be 0.6%. The cumulative incidences of PJI after 2 years in our study were slightly lower (0.22% for hips and 0.27% for knees) than results reported by CitationAinscow and Denham (1984) (0.27%). The cumulative incidences depend strongly on the length of the follow-up time and on case detection and definition (e.g. whether possible aseptic revisions and their infection complications are excluded).

The incidence rates of late or hematogenous PJI per prosthesis-year at risk was studied by CitationAinscow and Denham (1984) in a population of 1,112 total joint replacements with a mean follow-up time of 6 years. These authors reported an incidence of 0.04% per prosthesis-year. More recently, CitationCook et al. (2007) found an incidence of late PJI of 0.05% per prosthesis-year with an average follow-up time of 10 years in 3,013 total knee replacements similar to ours.

An increase in cumulative PJI incidences, including both postoperative and late PJIs, has been reported from the USA and the Nordic countries (CitationDale et al. 2012, CitationKurtz et al. 2012). In our study also, the incidence of very late PJI increased (but not statistically significantly) from 0.026% per prosthesis-year in 2004 to 0.056% per prosthesis-year in 2010. The reasons could not be analyzed in our study, and we cannot exclude the possibility that changes in the treatment protocols–namely the more active use of debridement and change of mobile parts with implant retention—have affected the possibility of PJIs being registered. Possible additional explanations include growing numbers of patients with predisposing comorbidities (CitationSingh and Lewallen 2014) and an increasing incidence of bacteremia (de CitationKraker et al. 2013).

In summary, according to our large nationwide study the risk of late PJI was approximately 0.07% per prosthesis-year, and it was higher for knees than for hips. During the study period, the incidence of PJIs that were registered very late (> 5 years after surgery) appeared to increase, which justifies future monitoring of the incidence of late PJI and study of the reasons for the increase.

Supplementary data

Tables 1–3 are available at Acta’s website (www.actaorthop.org), identification number 8258.

Supplementary Material

Download PDF (33.4 KB)Design of the study: KH and EJ. Data analysis and writing of the manuscript: KH, MP, and EJ.

The abstract was published at the thirty-third annual meeting of the European Bone and Joint Infection Society, Utrecht, the Netherlands (11–13 September 2014). Abstract book F120, pages 110-111.

- Ainscow DA , Denham RA . The risk of haematogenous infection in total joint replacements. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1984; 66 (4): 580–582.

- Altman D , Machin D , Bryant T , Gardner S . Statistics with confidence. 2nd edn. Oxford: BMJ Books, 2000.

- Cook JL , Scott RD , Long WJ . Late hematogenous infections after total knee arthroplasty: Experience with 3013 consecutive total knees. J Knee Surg 2007; 20 (1): 27–33.

- Dale H , Fenstad AM , Hallan G , Havelin LI , Furnes O , Overgaard S , et al . Increasing risk of prosthetic joint infection after total hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthop 2012; 83 (5): 449–58.

- de Kraker ME , Jarlier V , Monen JC , Heuer OE , van de Sande N , Grundmann H . The changing epidemiology of bacteraemias in Europe: Trends from the European antimicrobial resistance surveillance system. Clin Microbiol Infect 2013; 19 (9): 860–8.

- Huotari K , Lyytikäinen O , Ollgren J , Virtanen MJ , Seitsalo S , Palonen R , Rantanen P , Hospital Infection Surveillance Team. Disease burden of prosthetic joint infections after hip and knee joint replacement in Finland during 1999-2004: capture-recapture estimation. J Hosp Infect 2010; 75 (3): 205–8.

- Jämsen E , Huhtala H , Puolakka T , Moilanen T . Risk factors for infection after knee arthroplasty. A register-based analysis of 43,149 cases. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2009a; 91 (1): 38–47.

- Jämsen E , Huotari K , Huhtala H , Nevalainen J , Konttinen YT . Low rate of infected knee replacements in a nationwide series--is it an underestimate? Acta Orthop 2009b; 80 (2): 205–12.

- Jämsen E , Peltola M , Eskelinen A , Lehto MU . Comorbid diseases as predictors of survival of primary total hip and knee replacements: A nationwide register-based study of 96 754 operations on patients with primary osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2013; 72 (12): 1975–82.

- Kaandorp CJ , Dinant HJ , van de Laar MA , Moens HJ , Prins AP , Dijkmans BA . Incidence and sources of native and prosthetic joint infection: A community based prospective survey. Ann Rheum Dis 1997; 56 (8): 470–5.

- Kurtz SM , Ong KL , Lau E , Bozic KJ , Berry D , Parvizi J . Prosthetic joint infection risk after TKA in the Medicare population. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2010; 468 (1): 52–6.

- Kurtz SM , Lau E , Watson H , Schmier JK , Parvizi J . Economic burden of periprosthetic joint infection in the United States. J Arthroplasty 2012; 27 (8 suppl): 61, 5.e1.

- Maderazo EG , Judson S , Pasternak H . Late infections of total joint prostheses. A review and recommendations for prevention. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1988; 229 (Apr): 131–42.

- Mattila VM , Sillanpää P , Iivonen T , Parkkari J , Kannus P , Pihlajamäki H . Coverage and accuracy of diagnosis of cruciate ligament injury in the Finnish national hospital discharge register. Injury 2008; 39 (12): 1373–6.

- Nemes S , Gordon M , Rogmark C , Rolfson O . Projections of total hip replacement in Sweden from 2013 to 2030. Acta Orthop 2014; 85 (3): 238–43.

- NOMESCO classification of surgical procedures. Available at: http://nomesco-eng.nom-nos.dk/filer/publikationer/NCSP%201_15.pdf.

- Official statistics of Finland (OSF): Causes of death [e-publication]. ISSN=1799-5078. Helsinki: Statistics Finland. Available at: http://www.stat.fi/til/ksyyt/index_en.html.

- Ong KL , Kurtz SM , Lau E , Bozic KJ , Berry DJ , Parvizi J . Prosthetic joint infection risk after total hip arthroplasty in the Medicare population. J Arthroplasty 2009; 24 (6 suppl): 105–9.

- Peltola M , Juntunen M , Häkkinen U , Rosenqvist G , Seppälä TT , Sund R . A methodological approach for register-based evaluation of cost and outcomes in health care. Ann Med 2011; 43 (1 suppl): 4–13.

- Phillips JE , Crane TP , Noy M , Elliott TS , Grimer RJ . The incidence of deep prosthetic infections in a specialist orthopaedic hospital: A 15-year prospective survey. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2006; 88 (7): 943–8.

- Portillo ME , Corvec S , Borens O , Trampuz A . An underestimated pathogen in implant-associated infections. Biomed Res Int 2013; 2013: 804391.

- Pulido L , Ghanem E , Joshi A , Purtill JJ , Parvizi J . Periprosthetic joint infection: The incidence, timing, and predisposing factors. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2008; 466 (7): 1710–5.

- Puolakka TJ , Pajamäki KJ , Halonen PJ , Pulkkinen PO , Paavolainen P , Nevalainen JK . The Finnish arthroplasty register: Report of the hip register. Acta Orthop Scand 2001; 72 (5): 433–41.

- Sendi P , Banderet F , Graber P , Zimmerli W . Clinical comparison between exogenous and haematogenous periprosthetic joint infections caused by Staphylococcus aureus. Clin Microbiol Infect 2011; 17 (7): 1098–100.

- Singh JA , Lewallen DG . Time trends in the characteristics of patients undergoing primary total knee arthroplasty. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2014; 66 (6): 897–906.

- Sund R . Quality of the Finnish hospital discharge register: A systematic review. Scand J Public Health 2012; 40 (6): 505–15.

- Sund R , Nurmi-Luthje I , Luthje P , Tanninen S , Narinen A , Keskimäki I . Comparing properties of audit data and routinely collected register data in case of performance assessment of hip fracture treatment in Finland. Methods Inf Med 2007; 46 (5): 558–66.

- Tsaras G , Osmon DR , Mabry T , Lahr B , St Sauveur J , Yawn B , et al . Incidence, secular trends, and outcomes of prosthetic joint infection: A population-based study, Holmsted county, Minnesota, 1969-2007. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2012; 33 (12): 1207–12.

- Zimmerli W , Trampuz A , Ochsner PE . Prosthetic-joint infections. N Engl J Med 2004; 351 (16): 1645–54.