Abstract

Background and purpose — Postoperative muscle strength and component alignment are important factors affecting functional results after total knee arthroplasty (TKA). We are not aware of any studies that have investigated the relationship between them. We therefore investigated whether coronal malalignment of the mechanical axis and/or of individual implant components would affect knee muscle strength and function 1 year after TKA surgery.

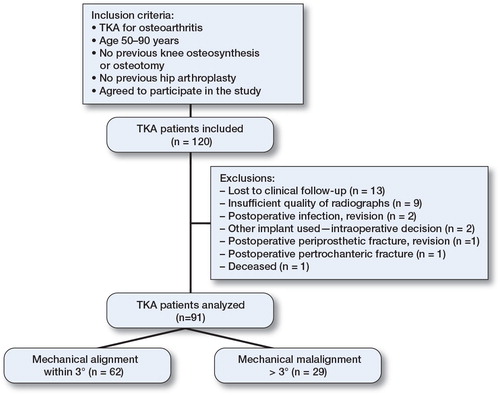

Patients and methods — We included 120 consecutive osteoarthritis (OA) patients admitted for TKA. Preoperative active range of motion (ROM) of the knee, patient age, sex, and BMI were recorded and the Knee Society score (KSS) and knee joint extensor/flexor muscle strength were assessed. At 1-year follow-up, the mechanical and coronal component alignment was measured from a postoperative long standing radiograph, and ROM, KSS, and muscle strength measurements were taken in 91 patients. Functional outcome and muscle strength measurements were compared between normally aligned and malaligned TKA groups.

Results — 29 of 91 TKAs were malaligned, i.e. they deviated more than 3° from the neutral mechanical axis. 18 femoral components and 15 tibial components were malaligned. Before surgery, the malaligned and normally aligned groups were similar regarding sex distribution, BMI, ROM, KSS, and muscle strength. At the 1-year follow-up, the differences between the groups regarding knee joint function and muscle strength were small, not statistically significant, and barely clinically relevant.

Interpretation — Moderate varus/valgus malalignment of the mechanical axis or of individual components has no relevant clinical effect on function or muscle strength 1 year after TKA surgery.

Failure to restore limb alignment in total knee arthroplasty (TKA) increases the risk of revision (CitationJeffery et al. 1991, CitationRitter et al. 1994 and Citation2011, CitationBerend et al. 2004), but the effect of accurate postoperative alignment on TKA function is controversial (CitationLotke and Ecker 1977, CitationChoong et al. 2009, CitationFang et al. 2009, CitationLongstaff et al. 2009, CitationHuang et al. 2012).

CitationHuang et al. (2012) reported that TKAs with a coronal alignment within 3° from the neutral axis had better function and quality of life at 5-year follow-up than TKAs that deviated more than 3° from neutral alignment. Other studies comparing computer-assisted TKA with conventional TKA surgery have not been able to correlate malalignment with inferior functional outcomes (CitationSpencer et al. 2007, CitationKamat et al. 2009, CitationKim et al. 2009, CitationBurnett and Barrack 2013).

Patients with greater preoperative muscle strength have been reported to have faster recovery and better functional outcome after TKA (CitationMizner et al. 2005, CitationYoshida et al. 2008). However, full recovery of muscle strength after TKA is uncommon (CitationBerth et al. 2002, CitationValtonen et al. 2009, CitationMaffiuletti et al. 2010, CitationVahtrik et al. 2012).

It is plausible that failure to restore the mechanical axis restoration results in inferior muscle function. CitationSogabe et al. (2009) found different cross-sectional areas in the quadriceps muscles with different knee alignments. They suggested that knees with varus or valgus deformation should have poorer muscle function compared to normally aligned knees. However, we have not been able find any studies investigating muscle strength after TKA in relation to component alignment and mechanical axis restoration.

We investigated whether coronal malalignment of the mechanical axis and/or of individual implant components would affect knee muscle strength and function 1 year after TKA surgery.

Patients and methods

We prospectively investigated 120 consecutive osteoarthritis (OA) patients who were admitted for elective TKA with one type of prosthesis (NexGen LPS; Zimmer, Warsaw, IN) ().

1 day before surgery, the active range of motion (ROM) in the affected knee was measured with a goniometer. The patient’s age, sex, height, weight, and body mass index (BMI) were recorded and their Knee Society score (KSS) was assessed using both objective subscales (pain, leg alignment, stability, and joint motion) and functional subscales (walking distance, stair climbing, and walking aids) (CitationInsall et al. 1989). Pain was evaluated according to KSS and graded (severe, moderate continual or occasional, mild while walking or in stairs or occasional, and none). The OA was graded preoperatively according Burnett’s radiographic atlas (CitationBurnett et al. 1994) in stages from 0 to 21. The preoperative knee extensor/flexor (quadriceps/hamstring) isometric muscle strengths were measured at 90° and 60° knee joint flexion angles using a Biodex System 4 Pro dynamometer (Biodex Medical Systems, Shirley, NY) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Each test was repeated twice and the average of the isometric peak torques was taken and adjusted to the patient’s body weight. In addition, hamstring-quadriceps ratios were calculated from the isometric peak torques. Isometric muscle strength evaluation has been reported as a valid and reliable assessment in TKA patients (CitationLienhard et al. 2013).

All arthroplasties were performed using the same cemented implants through a medial parapatellar approach. The patella was everted but not resurfaced. All operations were performed by 4 experienced consultants using spinal-epidural anesthesia.

At 1-year follow-up, ROM and KSS were assessed and muscle strength measurements were performed with the same methodology as preoperatively. Additionally, long standing lower extremity anterior-posterior radiographs were obtained at a focal distance of 2.5 m with a consistent stance: the patients were standing on both legs with patella facing forward and the medial aspects of both feet parallel (Jonsson and Boegard 2002). The overall mechanical alignment of the lower extremity was defined as the hip-knee-ankle (HKA) angle formed by the mechanical femoral and tibial axes (CitationSheehy et al. 2011). HKAs with a positive value were in varus and those with a negative value were in valgus. The coronal alignment of the femoral and tibial components in the frontal plane was also measured (), with the femoral component angle being defined as the angle medially between the distal surfaces of the femoral component and the femoral mechanical axis, and the tibial component angle being defined as the medial angle between the tibial component plateau and the tibial mechanical axis (CitationNg et al. 2012). The measurements were performed using a radiology viewer (Cedara I-Reach 4.4; Cedara Software Corp., Mississauga, ON, Canada). Radiological outliers were defined as TKAs in which the position of components and/or the mechanical axis measured deviated by more than 3° from the neutral mechanical axis.

Figure 2. Standing anterior-posterior radiograph with a varus malalignment. Mechanical axis as hip-knee-ankle (HKA) and component alignment angles are represented. The HKA angle is the angle formed between the mechanical femoral and tibial axes. The femoral component (FC) angle is the angle medially between the distal surfaces of the femoral component and the femoral mechanical axis. The tibial component (TC) angle is the medial angle between the tibial component plateau and the tibial mechanical axis.

Statistics

Data are presented as mean (SD) or mean difference with 95% confidence interval (CI). To determine whether the data were normally distributed, we performed a Shapiro-Wilk test for normality. As part of the data was not normally distributed, we used both parametric and non-parametric tests. As the calculated p-values were similar in terms of significance irrespective of the method used, the non-parametric tests were chosen for reporting of the data. We used the non-parametric Mann-Whitney test for independent samples and Wilcoxon test for paired samples. Fisher’s exact test was used when comparing proportions between the groups. Any p-value of < 0.05 was considered significant. We used SPSS software for the calculations.

Ethics

The study was approved by the regional biomedical research ethics committee (reference no. BE-2-5).

Results

91 of the 120 TKA patients remained for analysis at the 1-year follow-up (). Radiological data are presented in .

Table 1. Postoperative radiological data (mean (SD); °) for patients with hip-knee-ankle (HKA) angle and component alignment within ± 3° or > 3° (varus or valgus) from a straight mechanical axis

Regarding mechanical axis, 29 of 91 TKAs were malaligned, 24 in varus (3° to 11°) and 5 in valgus (−3° to −8°). In 12 of these 29 mechanically malaligned TKAs, both the femoral and the tibial components were normally aligned (< 3° deviation), although the combination led to an overall malalignment. The other 17 TKAs had malaligned components (9 femoral, 6 tibial, and 2 both). Of the 62 TKAs with a normal mechanical axis, 13 had malaligned components (6 femoral, 6 tibial, and 1 both).

Overall, 18 femoral components and 15 tibial components were malaligned. Of the 18 femoral components, 3 were in valgus and 15 were in varus (−5° to 5°). Of the 15 malaligned tibial components, 3 were in valgus and 12 were in varus (−4° to 5°).

Preoperatively, the malaligned and normally aligned groups were similar regarding sex distribution, BMI, OA grade, ROM, and KSS, but the mean age was statistically significantly lower in the malaligned femoral component group (71 (8) years as opposed to 67 (7) years) (Table 2, see supplementary data). Preoperative muscle strength or hamstring-quadriceps ratios were similar in normally aligned and malaligned knees (Table 3, see supplementary data).

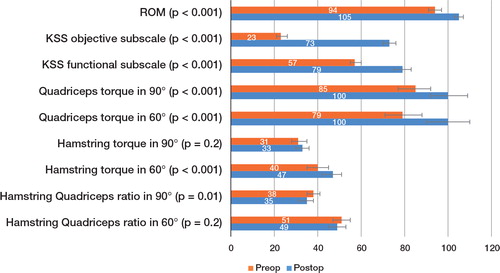

Comparing muscle strength before and 1 year after the TKA, a significant improvement was found in 3 of 4 measurements (), as well as in ROM and KSS. As only quadriceps, but not hamstring torque, improved there was a postoperative worsening in hamstring-quadriceps ratio in the 90° position. This was not the case for the 60° position, where both quadriceps and hamstring torque improved, so the hamstring-quadriceps ratio in 60° position did not change significantly (). A further comparison of muscle strength, hamstring-quadriceps ratio, KSS, and ROM between normally aligned and malaligned groups did not reveal any statistically significant differences at the 1-year follow-up (Table 3, see supplementary data, and ).

Figure 3. Comparisons of mean (with 95% CI; whiskers) ROM (°), KSS (points), muscle torques (Nm), and hamstring-quadriceps ratios (%) (n = 91) preoperatively and postoperatively.

Table 4. Postoperative ROM, KSS objective, functional and pain assessment subscale (ss) results (mean (SD), mean difference with 95% confidence intervals (CI), or rates) between patients with mechanical and component alignment within ± 3° and > 3°

Discussion

The radiological definition of “normally” aligned TKA knees is debated (Abdel et al. 2014, CitationGromov et al. 2014), but most papers on implant survival and radiological alignment have used some deviation from the mechanical or anatomical coronal axis for definement of malalignment. Several studies have used a deviation of 3° from a neutral alignment as a threshold for what is acceptable for good long-term results (CitationJeffery et al. 1991, CitationRitter et al. 1994 and 2011, CitationBerend et al. 2004). Such a 3° threshold has also been chosen in numerous other studies investigating results after TKA (CitationChoong et al. 2009, CitationLongstaff et al. 2009, CitationParratte et al. 2010, CitationHuang et al. 2012), and an alignment within 3° of the mechanical axis has been considered to be the gold standard (Lombardi et al. 2011). Based on this, we decided to use a deviation from the neutral mechanical axis of 3° as the threshold between normally aligned and malaligned TKA knees.

We found that one third of the patients had a mechanical axis that deviated from 3° to 11° from the neutral mechanical axis, with 20% of the femoral components and 16% of the tibial components being outliers (> 3° varus or valgus). Similar proportions of components and axis malalignment after conventional TKA was observed by CitationHuang et al. (2012), who reported malalignment of > 3° in up to one third of conventional TKAs, but up to two-thirds has been reported (CitationHaaker et al. 2005).

The accurate restoration of axis and correct implantation of components is of importance, as it may affect the survival of the TKA. CitationJeffery et al. (1991) reported 24% loosening if the deviation from neutral axis after TKA exceeded 3° (as compared to 3% loosening in normally aligned knees). Concerning the positioning of components, it has been reported that more than 3° of varus malalignment of the tibial component has a higher incidence of failure (CitationHsu et al. 1989, CitationBerend et al. 2004), and on the femoral side it has also been reported that an isolated malalignment increases the risk of failure (CitationRitter et al. 2011). Such increased failure risk may be explained by uneven distribution of load on the bone (medial bone collapse) or on the polyethylene insert, causing greater wear and subsequent osteolysis. However, the effect of malalignment on the muscles around the knee in the short term has not been thoroughly investigated after TKA.

When comparing normally aligned and moderately malaligned TKAs both pre- and postoperatively, we found that muscle strength was similar between the groups. The same applied for KSS and ROM, where the differences were small and hardly clinically relevant (Table 2, see supplementary data, and ). This is in agreement with the results of CitationMatziolis et al. (2010), who reported that postoperative varus malalignment as compared to neutral knee alignment after TKA had no influence on clinical outcome (KSS, the WOMAC, and the SF36). Furthermore, CitationMagnussen et al. (2011) even found KSS to be better in patients with residual varus than in those with neutral alignment. However, there have been reports showing the opposite; CitationChoong et al. (2009) and CitationHuang et al. (2012) reported better KSS in TKA patients with a mechanical axis within 3° than in those with malaligned knees, which remained consistent from 6 weeks to 5 years of follow-up. We have no clear explanation for these contradictory findings, but CitationChoong et al. (2009) and CitationHuang et al. (2012) included patients with a variety of preoperative diagnoses, different implant types, and use of patellar resurfacing—which may have influenced the results. In contrast, our study only included OA patients with the same type of implant and no patellar resurfacing.

A weakness of the present study was that the rotation of femoral and tibial components was not measured. Malrotation of femoral or tibial components has been correlated with pain and inferior function (CitationBarrack et al. 2001, CitationPietsch and Hofmann 2012), which could have an effect on KSS and muscle strength. However, none of the patients included in this study were revised due to a painful knee (according to the KSS objective subscale) before the end of the 1-year follow-up. In addition, another possible weakness of our study was that we did not measure pain during muscle strength assessment. One might suspect that during the examination, a painful knee would have had some influence on the muscle strength. However, in our material the mean KSS pain assessments or grades, which were recorded just before the muscle strength measurements, showed no statistically or clinically significant differences between normally aligned and malaligned TKA knees. Another weakness of the study was that we did not investigate the alignment in the sagittal plane for posterior offset and tilting of femoral component, or tibial slope. These parameters could possibly affect ROM and muscle strength.

In the present study, postoperative muscle strength 1 year after surgery exceeded the preoperative strength in 3 out of every 4 measurements. Similar findings were reported by CitationBerth et al. (2002) and CitationYoshida et al. (2008), who investigated muscle strength from 1 to 3 years after TKA and observed an increase relative to preoperative values. However, CitationVahtrik et al. (2012), who investigated muscle strength at 3 and 6 months after TKA, found that postoperative muscle strength was lower than the preoperative value. Thus, it may be that after TKA surgery, the recovery and improvement of muscle strength can take more than 6 months.

We did not find that TKA malalignment had a statistically significant effect on muscle strength and function at the 1-year follow-up, so any subsequently higher failure rates caused later by malaligned TKAs are unlikely to be directly related to the function of the surrounding muscles. It appears that muscles can adapt to a malaligned axis or components without loss of strength, and can also produce function similar to that in normally aligned TKAs.

We conclude that moderate varus/valgus malalignment of the mechanical axis, or of individual components, has no relevant clinical effect on function or muscle strength 1 year after TKA surgery.

Supplementary data

Tables 2 and 3 are available at Acta’s website (www.actaorthop.org), identification number 7800.

IORT_A_1059689_SM1686.pdf

Download PDF (35.8 KB)JS: data collection, measurements, data analysis, and writing of manuscript. AS and AL: data collection and analysis, and editing of manuscript. OR, HW, and ST: organization of study, data analysis, and editing of manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

We acknowledge with gratitude the work done by sports medicine physicians who measured the muscle strength, and by the radiology department. The research was funded by a grant from the Research Council of Lithuania (no. MIP-11202).

No competing interests declared.

- Abdel MP, Oussedik S, Parratte S, Lustig S, Haddad FS. Coronal alignment in total knee replacement: historical review, contemporary analysis, and future direction. Bone Joint J 2014; 96-B(7): 857-62.

- Barrack RL, Schrader T, Bertot AJ, Wolfe MW, Myers L. Component rotation and anterior knee pain after total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop 2001; (392): 46-55.

- Berend ME, Ritter MA, Meding JB, Faris PM, Keating EM, Redelman R, Faris GW, Davis KE. Tibial component failure mechanisms in total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop 2004; (428): 26-34.

- Berth A, Urbach D, Awiszus F. Improvement of voluntary quadriceps muscle activation after total knee arthroplasty. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2002; 83(10): 1432-6.

- Burnett S, Hart DJ, Cooper C, et al. A radiographic atlas of osteoarthritis. Springer, London 1994.

- Burnett RS, Barrack RL. Computer-assisted total knee arthroplasty is currently of no proven clinical benefit: a systematic review. Clin Orthop 2013; 471(1): 264-76.

- Choong PF, Dowsey MM, Stoney JD. Does accurate anatomical alignment result in better function and quality of life? Comparing conventional and computer-assisted total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2009; 24: 560–569.

- Fang DM, Ritter MA, Davis KE. Coronal alignment in total knee arthroplasty: just how important is it? J Arthroplasty 2009; 24(6 Suppl): 39-43.

- Gromov K, Korchi M, Thomsen MG, Husted H, Troelsen A. What is the optimal alignment of the tibial and femoral components in knee arthroplasty? Acta Orthop 2014; 85(5): 480-7.

- Haaker RG, Stockheim M, Kamp M, Proff G, Breitenfelder J, Ottersbach A. Computer-assisted navigation increases precision of component placement in total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop 2005; 433: 152-9.

- Hsu HP, Garg A, Walker PS, Spector M, Ewald FC. Effect of knee component alignment on tibial load distribution with clinical correlation. Clin Orthop 1989; (248): 135-44.

- Huang NF, Dowsey MM, Ee E, Stoney JD, Babazadeh S, Choong PF. Coronal alignment correlates with outcome after total knee arthroplasty: five-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. J Arthroplasty 2012; 27(9): 1737-41.

- Insall JN, Dorr LD, Scott RD, Scott WN. Rationale of the knee society clinical rating system. Clin Orthop 1989; 248: 13–4.

- Jeffery RS, Morris RW, Denham RA. Coronal alignment after total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1991; 73(5): 709-14.

- Jonsson K, Boegard T. Radiography. In: Davies AM, Cassar-Pullicino VN ed. Imaging of the Knee: Techniques and Applications. Springer-Verlag, Berlin Heidelberg 2002: 3-16.

- Kamat YD, Aurakzai KM, Adhikari AR, Matthews D, Kalairajah Y, Field RE. Does computer navigation in total knee arthroplasty improve patient outcome at midterm follow-up? Int Orthop 2009; 33(6): 1567-70.

- Kim YH, Kim JS, Choi Y, Kwon OR. Computer-assisted surgical navigation does not improve the alignment and orientation of the components in total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2009; 91(1): 14-9.

- Lienhard K, Lauermann SP, Schneider D, Item-Glatthorn JF, Casartelli NC, Maffiuletti NA. Validity and reliability of isometric, isokinetic and isoinertial modalities for the assessment of quadriceps muscle strength in patients with total knee arthroplasty. J Electromyogr Kinesiol 2013; 23(6): 1283-8.

- Lombardi AVJr, Berend KR, Ng VY. Neutral mechanical alignment: a requirement for successful TKA: affirms. Orthopedics 2011; 34 (9): e504-6.

- Longstaff LM, Sloan K, Stamp N, Scaddan M, Beaver R. Good alignment after total knee arthroplasty leads to faster rehabilitation and better function. J Arthroplasty 2009; 24: 570-8.

- Lotke PA, Ecker ML. Influence of positioning of prosthesis in total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1977; 59: 77-9.

- Maffiuletti NA, Bizzini M, Widler K, Munzinger U. Asymmetry in quadriceps rate of force development as a functional outcome measure in TKA. Clin Orthop 2010; 468(1): 191-8.

- Magnussen RA, Weppe F, Demey G, Servien E, Lustig S. Residual varus alignment does not compromise results of TKAs in patients with preoperative varus. Clin Orthop 2011; 469(12): 3443-50.

- Matziolis G, Adam J, Perka C. Varus malalignment has no influence on clinical outcome in midterm follow-up after total knee replacement. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2010; 130 (12): 1487-91.

- Mizner RL, Petterson SC, Snyder-Mackler L. Quadriceps strength and the time course of functional recovery after total knee arthroplasty. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2005; 35(7): 424-36.

- Ng VY, DeClaire JH, Berend KR, Gulick BC, Lombardi AVJr. Improved accuracy of alignment with patient-specific positioning guides compared with manual instrumentation in TKA. Clin Orthop 2012; 470(1): 99-107.

- Parratte S, Pagnano MW, Trousdale RT, Berry DJ. Effect of postoperative mechanical axis alignment on the fifteen-year survival of modern, cemented total knee replacements. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2010; 92: 2143-9.

- Pietsch M, Hofmann S. Early revision for isolated internal malrotation of the femoral component in total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2012; 20(6): 1057-63.

- Ritter MA, Faris PM, Keating EM, Meding JB. Postoperative alignment of total knee replacement: its effect on survival. Clin Orthop 1994; 299:153–156.

- Ritter MA, Davis KE, Meding JB, Pierson JL, Berend ME, Malinzak RA. The effect of alignment and BMI on failure of total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2011; 93(17): 1588-96.

- Sheehy L, Felson D, Zhang Y, Niu J, Lam YM, Segal N, Lynch J, Cooke TD. Does measurement of the anatomic axis consistently predict hip-knee-ankle angle (HKA) for knee alignment studies in osteoarthritis? Analysis of long limb radiographs from the multicenter osteoarthritis (MOST) study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2011; 19(1): 58-64.

- Sogabe A, Mukai N, Miyakawa S, Mesaki N, Maeda K, Yamamoto T, Gallagher PM, Schrager M, Fry AC. Influence of knee alignment on quadriceps cross-sectional area. J Biomech 2009; 42(14): 2313-7.

- Spencer JM, Chauhan SK, Sloan K, Taylor A, Beaver RJ. Computer navigation versus conventional total knee replacement: no difference in functional results at two years. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2007; 89(4): 477-80.

- Vahtrik D, Gapeyeva H, Aibast H, Ereline J, Kums T, Haviko T, Märtson A, Schneider G, Pääsuke M. Quadriceps femoris muscle function prior and after total knee arthroplasty in women with knee osteoarthritis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2012; 20(10): 2017-25.

- Valtonen A, Pöyhönen T, Heinonen A, Sipilä S. Muscle deficits persist after unilateral knee replacement and have implications for rehabilitation. Phys Ther 2009; 89: 1072–9.

- Yoshida Y, Mizner RL, Ramsey DK, Snyder-Mackler L. Examining outcomes from total knee arthroplasty and the relationship between quadriceps strength and knee function over time. Clin Biomech 2008; 23(3): 320-8.