Abstract

Background and purpose — We hypothesized that an ultra-short stem would load the proximal femur in a more physiological way and could therefore reduce the adaptive periprosthetic bone loss known as stress shielding.

Patients and methods — 51 patients with primary hip osteoarthritis were randomized to total hip arthroplasty (THA) with either an ultra-short stem or a conventional tapered stem. The primary endpoint was change in periprosthetic bone mineral density (BMD), measured with dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA), in Gruen zones 1 and 7, two years after surgery. Secondary endpoints were change in periprosthetic BMD in the entire periprosthetic region, i.e. Gruen zones 1 through 7, stem migration measured with radiostereometric analysis (RSA), and function measured with self-administered functional scores.

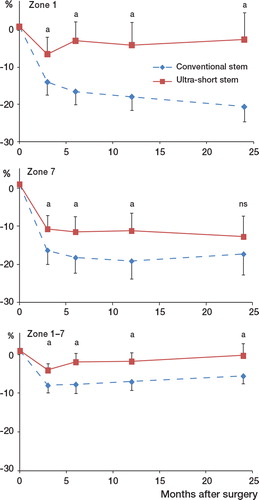

Results — The periprosthetic decrease in BMD was statistically significantly lower with the ultra-short stem. In Gruen zone 1, the mean difference was 18% (95% CI: −27% to −10%). In zone 7, the difference was 5% (CI: −12% to −3%) and for Gruen zones 1–7 the difference was also 5% (CI: −9% to −2%). During the first 6 weeks postoperatively, the ultra-short stems migrated 0.77 mm more on average than the conventional stems. 3 months after surgery, no further migration was seen. The functional scores improved during the study and were similar in the 2 groups.

Interpretation — Up to 2 years after total hip arthroplasty, compared to the conventional tapered stem the ultra-short uncemented anatomical stem induced lower periprosthetic bone loss and had equally excellent stem fixation and clinical outcome.

Periprosthetic bone loss in uncemented femoral stems can contribute to late-occurring periprosthetic fractures (CitationLindahl 2007, CitationStreit et al. 2011). This is partly mediated by adaptive bone resorption. This disuse atrophy, known as stress shielding, is mainly a consequence of the mismatch in modulus of elasticity between the implant and the periprosthetic bone. In time, the increasingly more fragile periprosthetic bone may break—even after minor trauma. Shorter femoral stems, aimed at giving a more physiological load pattern in the proximal femur, have become popular lately because of expectations of reducing stress shielding. Absence of a diaphyseal engaging stem is a key factor to prevent off-loading of the proximal femoral bone, but at the same time it will challenge the primary stability necessary for bone osseointegration of the femoral implant (CitationSøballe et al. 1992).

In this study, we hypothesized that an ultra-short uncemented stem would give less periprosthetic bone loss in the proximal femur than a conventional tapered uncemented stem, and that the ultra-short stem would achieve good fixation and be safe to use from a clinical standpoint.

Patients and methods

Trial design

We conducted a prospective, randomized controlled trial between October 2009 and August 2013, at the orthopedic department, Danderyd Hospital, in collaboration with the Department of Clinical Sciences at Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm. We followed the guidelines of the CONSORT statement (CitationSchulz et al. 2010).

Participants

We recruited patients with primary osteoarthritis who were scheduled for total hip arthroplasty (THA). Inclusion criteria were 40–70 years of age with bone stock suitable for uncemented hip arthroplasty, i.e. femur type Dorr A or B (CitationDorr et al. 1993), and femoral anatomy allowing implantation of both stem types, i.e. no hip dysplasia and no previous hip surgery on the affected side. We excluded patients who had taken corticosteroids, bisphosphonates, or cytostatic drugs on a regular basis in the 6 months prior to surgery. Even other drugs acting on bone metabolism (such as denosumab and teriparatide) were an exclusion criterion. BMI above 35 was also set as an exclusion criterion because obesity was thought to increase the technical difficulties at the surgical procedure and therefore possibly influence the outcome.

Implants

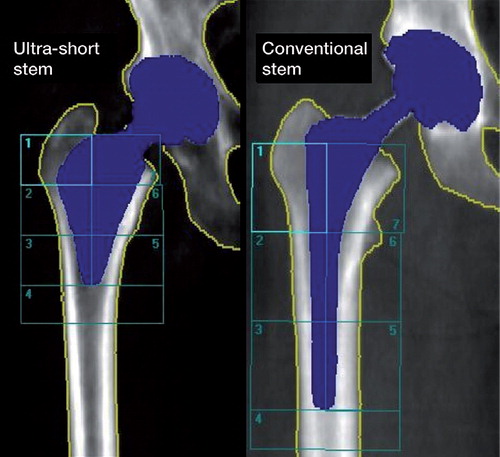

The treatment group received an ultra-short wedge-shaped porous and HA-coated titanium stem (Proxima; Depuy Johnson and Johnson). The control group received a proximally porous and HA-coated, conventional tapered titanium stem (Bi-metric; Biomet) ( and ). A modular 32-mm cobalt-chrome head was used together with an uncemented press-fit cup with a highly crosslinked ultra-high-molecular-weight polyethylene (HXLPE) liner from the same manufacturer as the stem. Design rationales for the ultra-short stem are an anatomical wedge shape, a prominent lateral flare, and absence of a diaphyseal stem. These features are claimed by the manufacturer to provide initial stability both vertically and rotationally and, together with a high horizontal neck resection, ensure load transfer to both the medial and the lateral aspects of the proximal femoral metaphysis (CitationWalker et al. 1999, CitationRenkawitz et al. 2008, CitationToth et al. 2010). The macrotexture of the surface is stepped to increase ingrowth area and to transform tangential forces into compressive loads to the bone (CitationGhera and Pavan 2009).

Table 1. Stem characteristics

Surgery

Surgery was performed by 5 senior surgeons using a posterolateral approach (CitationMoore 1957) with repair of the posterior capsule and the external rotator muscles (CitationKwon et al. 2006). Local infiltration analgesia with ropivacain, ketorolak, and epinephrine was given peroperatively. Immediate full weight bearing was allowed.

Before the study started, all surgeons practiced with the ultra-short stem on cadavers and a pilot series of 19 consecutive hip replacements was conducted. The conventional stem, evaluated as control, has been used extensively in our practice—with more than 2,000 implanted stems since 1990 and with excellent clinical and radiographic results (CitationBodén et al. 2006).

Primary endpoint

The primary endpoint was change in periprosthetic bone mineral density (BMD) in Gruen zones 1 and 7 after 2 years. Because of the difference in stem lengths, the Gruen zones differed in size between the 2 stem types. We therefore analyzed Gruen zones 1 and 2 as one zone in the ultra-short stem and compared that to zone 1 in the conventional stem (). By doing so, the proximal zones in both stems were anatomically comparable and easily reproducible. For the same reason, we analyzed zones 6 and 7 as one zone in the ultra-short stem and compared it to zone 7 in the conventional stem.

Secondary endpoints

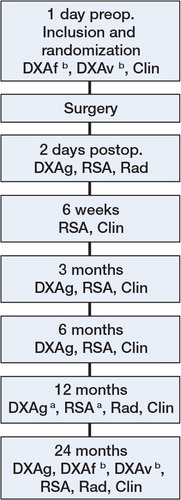

The secondary endpoints were change in periprosthetic BMD in the entire periprosthetic region (i.e. Gruen zones 1 through 7), stem migration, and the functional clinical result. The follow-up protocol is shown in .

Figure 3. Study protocol. DXAf: DXA scan of proximal femur (WHO total hip); DXAv: DXA scan of vertebrae L1–L4 (WHO lumbar spine); DXAg: DXA scan of Gruen zones; RSA: radiostereometry radiographs; Rad: anterioposterior and lateral conventional radiographs; Clin: clinical outcome scores including Harris hip score (HHS), WOMAC, and EQ-5D.

Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry

DXA scanning was done using a Lunar Prodigy Advance machine from General Electric Healthcare. The change in BMD in each zone was calculated by dividing the BMD value from each examination by the baseline value measured 2 days postoperatively. The ratio was expressed as a percentage of the baseline value. Patients were scanned supine with foot positioning support, to get reproducible internal hip rotation (CitationMortimer et al. 1996). The DXA scanner software subdivided the stem into 3 sections of equal length. The stem tip was the default starting reference point and the length of each section was dependent on the stem length, which was given by the stem manufacturer. Each patient’s individual regions of interest (ROIs) were saved and used for subsequent examinations to reduce measurement error. To calculate BMD precision, we performed duplicate examinations in every patient at 12 months by repositioning of patients (). Precision was calculated as the coefficient of variation in percent, CV%.

Table 2. Precision of DXA measurements expressed as coefficients of variation in percent (CV%)

An interobserver variability test between the 2 physicists responsible for the DXA analyses showed good agreement (p = 1.0).

We scanned the lumbar spine and the opposite hip according to the WHO criteria for measurement of each patient’s preoperative skeletal bone mass. At the 2-year follow-up, we re-scanned the lumbar spine and the healthy, contralateral hip, to calculate each patient’s loss of skeletal bone mass over time.

Radiostereometry

The secondary endpoint, stem migration, was evaluated with radiostereometric analysis (RSA). Due to lack of RSA-marked implants, we used the maximum total point motion (MTPM) of the center of the head of the femoral stem as the outcome variable for migration. Pythagoras’ theorem was used to calculate varus migration of the stems from migration along the horizontal and vertical axes. UmRSA 6.0 computer software (RSA Biomedical AB, Sweden) was used together with a uniplanar calibration cage 43 from the same manufacturer. Digital calibrated stereo radiographs (Bucky Diagnostic; Philips, the Netherlands) were taken using one fixed and one mobile Roentgen source. We followed the published guidelines for radiostereometric analysis (CitationValstar et al. 2005). Mean error of body fitting < 0.3 mm and condition number < 120 were set as cut-off limits to be included in the RSA analysis. At the 1-year follow-up, we performed duplicate RSA examinations on every patient. By multiplying the standard deviation of the differences between the 2 examinations by the appropriate t-value, we obtained the 99% precision interval. The precision for MTPM was 0.54 mm.

Clinical outcome

The clinical result was evaluated with self-administered scores at each follow-up. The hip-specific outcome scores used were Harris hip score (HHS) and Western Ontario and McMaster Universities osteoarthritis index (WOMAC). The health-related quality of life was measured with EuroQol 5-dimensions (EQ-5D). Mid-thigh pain was graded as none, mild, moderate, or severe.

Sample size and power analysis

Before the study, we conducted a power analysis based on data obtained from an earlier study of THA performed using the conventional stem (CitationSköldenberg et al. 2006). In a previous study of hip fracture prevention, a 4.8% increase in BMD in the greater trochanter and a 3.4% increase in BMD in the femoral neck (roughly equivalent to Gruen zones 1 and 7) was associated with a 30% reduction in hip fracture risk (CitationMcClung et al. 2001). We therefore assumed that a difference in BMD between our groups of 15% in the proximal zones (roughly 3 times as large as the increase in that study) would also be clinically relevant for our group of osteoarthritis patients, to reduce the incidence of late periprosthetic femoral fractures. A power analysis showed that detection of a 15% difference in BMD at the 5% significance level with a standard deviation of 14% (CitationSköldenberg et al. 2006) would require 17 patients in each group. We did not predefine the use of Bonferroni correction for the primary endpoint. To compensate for possible dropouts, we included 25 patients in each group.

Randomization

Since preoperative skeletal bone mass influences periprosthetic bone loss after hip arthroplasty (CitationNishii et al. 1997, CitationRahmy et al. 2004, CitationAlm et al. 2009), we stratified the randomization for age and sex. To obtain comparable groups, 2 age strata were used: 40–59 and 60–70 years of age. Each stratum consisted of blocks of 4. Patients were randomly assigned at a 1:1 ratio to either “ultra-short stem” or “conventional stem”. Randomization was carried out using sequentially numbered, opaque sealed envelopes. A research nurse generated the random allocation sequence. None of the surgeons involved in recruiting and operating on the patients were involved in the randomization process.

Statistics

Subjects with missing BMD data or missing migration data at any of the follow-up visits were analyzed by carrying the last observation forward. This was done with missing data for 1 follow-up visit in 2 patients. Bone mass data and stem migration data were tested for normality and homogeneity using Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and Levene’s test. Student’s t-test was used for between-group comparisons of BMD and a post-hoc Bonferroni correction (not included in the original study plan) was applied to the primary endpoint to handle multiplicity. Mann-Whitney U-test was used for between-group comparisons of stem migration, since these data were not normally distributed, and for clinical score data because these were ordinal data. No statistically significant difference was found in the amount of stem migration for the 5 surgeons using Kruskal-Wallis test (p = 0.5).

We used a linear regression analysis to reduce variance, and adjusted for group (ultra-short stem/conventional stem) and stratification factors (age (40–59/60–70) and sex) in order to evaluate the primary endpoint. SPSS 22.0 was used for the statistical analyses.

Ethics and registration

The local ethics committee approved the design and conduct of the clinical trial (number 2008/4:3). The trial is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (number NCT01319227). There, the primary endpoint was originally—incorrectly—set at all follow-ups, instead of the anticipated endpoint at 24 months only.

Results

Characteristics of participants

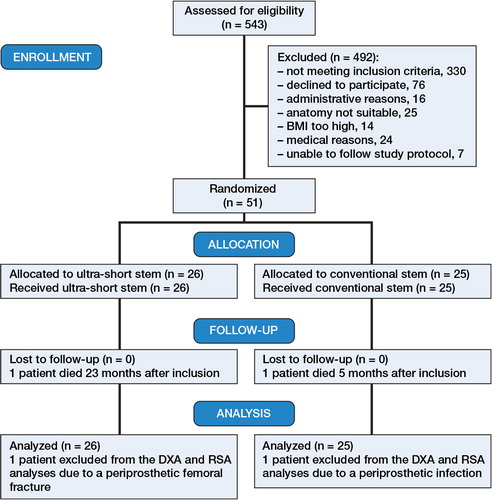

We included a fifty-first patient, because 1 patient died 5 months after inclusion—of causes unrelated to surgery (). Baseline characteristics such as demographic parameters, functional scores, and preoperative skeletal bone mass were similar in the 2 study groups (). The distributions of femoral bone type according to Dorr’s classification in the 2 age strata were 14 type A and 2 type B in the younger age group and 12 type A and 23 type B in the older group.

Table 3. Baseline characteristics of the study participants

Femoral bone remodeling

At 2 years, the decrease in BMD in zone 1 was lower for the ultra-short stems, with a mean difference of 18% (95% CI: –27% to –10%; p < 0.001) compared to the control group. In zone 7, the difference was 5% (95% CI: –12% to –3%; p = 0.4), with less BMD reduction in the ultra-short stems, but it was not statistically significant after 2 years. When we compared BMD in the entire periprosthetic region, i.e. Gruen’s zones 1–7 together as an entity, we found 5% lower bone resorption (95% CI: –9% to –2%; p = 0.02) in the ultra-short relative to the conventional group ( and ).

Table 4. Change (mean (SD) %) in bone mineral density (BMD)

Figure 5. Mean percentage change in BMD. Error bars indicate 95% CI. Differences were analyzed with Student’s t-test. a p < 0.05.

In the regression analysis, the results for the primary endpoint remained in favor of the ultra-short stems after adjustments for stratification factors. No statistically significant loss in skeletal bone mass (lumbar spine) after 2 years was found in the 2 groups.

Implant migration

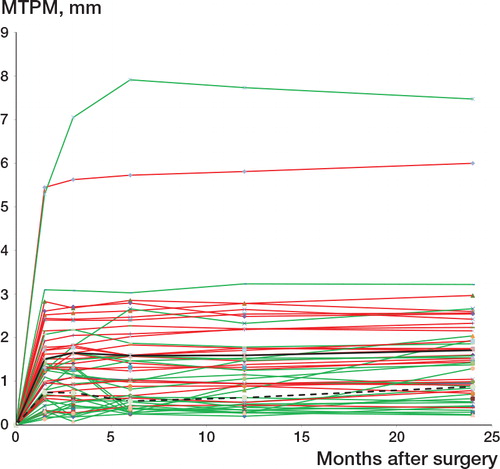

During the first 6 weeks postoperatively, the ultra-short stems migrated 0.77 mm more than the conventional stems (). Migration was predominately into varus and the statistically significant difference in varus migration at 6 weeks remained unchanged during subsequent follow-ups. No statistically significant difference was seen in migration along the sagittal axis. 3 months after surgery, no further migration was seen in the 2 groups and all implants were stable at 2 years ().

Table 5. Stem migration as maximum total point motion (MTPM) measured with radiostereometry (RSA). Values are median (range) mm.

Clinical outcome

Both median HHS and median WOMAC score improved greatly from baseline up to 2 years after surgery. Median HHS increased by 42 points to 95 for the ultra-short stem, compared to an increase of 38 points to 92 for the conventional stem. The difference in improvement and the results after 2 years were not statistically significant between the 2 groups (p = 0.2 and p = 0.2). WOMAC score increased by 48 points to 95 for the ultra-short stem and by 42 points to 94 for the conventional stem (p = 0.09 and p = 0.5). The improvement in health-related quality of life was also similar. Median EQ-5D increased in both groups from 0.69 preoperatively to 1.00 at 2-year follow-up. The number of patients who suffered from mid-thigh pain was greater in the conventional stem group during the first 6 months, but the differences were not statistically significant at any time ().

Table 6. Adverse events during the study

Adverse events

1 patient in the ultra-short stem group felt a sudden pain in the operated hip 3 weeks after surgery. Radiographs revealed a gross varus migration as a result of a calcar femoral fracture. The patient was revised to a conventional stem. 1 patient in the conventional stem group suffered from increasing hip pain, starting several months after surgery. He was diagnosed with a low-virulence deep periprosthetic infection. These 2 patients were excluded from the analyses. During the study period, 2 patients in the ultra-short stem group had been treated with glucocorticosteriods and bisphosphonates, for 7 and 10 months respectively, because of polymyalgia rheumatica. 1 patient in the conventional stem group was treated with tamoxifen (anti-estrogen). They were included in the data analyses according to the intention-to-treat-principle. Other adverse events were evenly distributed between the 2 groups (). We did not see any aseptic loosening, dislocation, or thromboembolic events.

Discussion

In this randomized, controlled trial in healthy patients with primary osteoarthritis and good preoperative bone quality, the ultra-short stem reduced short-term adaptive periprosthetic bone resorption in the greater trochanteric region and also along the entire periprosthetic region measured as an entity (Gruen zones 1–7).

As a result of the absence of a diaphyseal stem, the ultra-short stem—reaching just slightly distal to the level of the lesser trochanter—violated the femoral canal less than the conventional stem during preparation. However, this ultra-short design made it somewhat more prone to initial migration, predominantly in varus, before osseointegration occurred. We did not see any continuous migration after 3 months for the 2 stem types. Excellent improvements in clinical scores were recorded in both groups. There was a trend of less mid- thigh pain during the first 6 months in the ultra-short stem group.

Bone remodeling

The hypothetical rationale for the lateral flare—to transfer load to the greater trochanteric bone—appears to be a correct assumption by the implant designers. It is evidently an important design feature that might reduce the incidence of late periprosthetic fractures and/or trochanteric avulsions (CitationLindahl 2007, CitationStreit et al. 2011).

A reduction in BMD loss in the calcar region was also seen with the ultra-short stem until 1 year after surgery, but the difference was no longer statistically significant at 2 years. The trend of bone preservation in the calcar region could be an effect of load transfer from the prolonged medial contour of the ultra-short stem on the preserved calcar bone after a high neck resection level. Because of the stiffness of the titanium stem, the surrounding bone will demineralize according to Wolf’s law and load will be delivered to the skeleton mainly at the distal stem/bone interface. The shorter this distance, the less femoral bone will be shielded, indicating that stem length matters in preserving femoral bone. At least up to 2 years after surgery, the ultra-short stem preserves femoral bone, which is advantageous should a later stem revision be necessary. Bone remodeling in the control group was in accordance with an earlier study with this stem by our research group (CitationSköldenberg et al. 2011). In a study of the current ultra-short stem, CitationKim et al. (2011a) found bone remodeling in accordance with our results.

Short femoral stems, with differing shape and surface finish, have recently become popular because of similar expectations in reducing stress shielding, by loading the proximal femur in a more physiological way. Excellent clinical and radiographic mid-term results have been reported, but most of the short stems have not been able to reduce BMD loss in the proximal femoral regions (CitationAlbanese et al. 2009, CitationChen et al. 2009, CitationGotze et al. 2010, CitationLerch et al. 2012, CitationLazarinis et al. 2013).

Migration

An obvious risk in using short uncemented stems is that initial stability is challenged due to the lack of a stabilizing press-fit stem down the diaphysis. Varus malalignment and initial varus migration of the current ultra-short stem have been observed by several authors (CitationToth et al. 2010, Ghera and Pavan 2009), as well as varus malalignment of conventional uncemented stems (CitationKhalily and Lester 2002, CitationBerend et al. 2007, CitationMin et al. 2008). We did not use intraoperative fluoroscopy, which would explain why some of our stems were implanted slightly in varus. As our RSA results revealed, we also saw larger varus migration in the ultra-short stems than in the conventional stems initially after surgery. It seems as if a slight varus malalignment does not preclude either osseointegration or the favorable lateral periprosthetic bone remodeling, or the excellent clinical results.

Excessive early migration and continuous migration of an implant may predict implant loosening (CitationKärrholm et al. 1994, CitationKärrholm 2012). The amount of migration recorded for the ultra-short stem was slightly greater than the proposed safe zone for later loosening, but the proposed safe zone does not necessarily apply to an ultra-short stem. We interpreted the initial micromotion as a ”bedding-in” process before osseointegration has occurred.

Clinical results

Excellent clinical results have been reported with a variety of uncemented stems (CitationBourne et al. 2001, CitationAldinger et al. 2003, CitationBodén et al. 2006, CitationSanz-Reig et al. 2011). We observed equally excellent clinical results with the ultra-short stem in patients with adequate bone stock. However, we do not know whether we would get similar results in patients with compromised bone stock, even though others have used the same stem in elderly patients and reported generally good results (CitationKim et al. 2011b, CitationKim and Oh 2012). A gross subjective evaluation revealed a slightly lower incidence of thigh pain in the ultra-short stem group. In our opinion, patient selection and surgical technique are crucial factors for a successful outcome. This randomized study was preceded by a pilot series, where we found that choosing the largest stem size possible, especially in the A-P-plane, was of importance to obtain good initial stability. In the pilot series, we had 2 patients with aseptic loosening of the stem due to insufficient primary stability. We believe that the pilot series contributed to the low complication rate and excellent clinical results in the current study.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths were the prospective randomized study design, with a high follow-up rate, and that highly sensitive and accurate methods were used to evaluated our endpoints. In addition, the analysis of effect was performed according to the intention-to-treat principle, an approach that has been lacking, or not reported, in most previously published studies on bone remodeling. The lack of patient blinding was the main limitation of the study. Also, a more accurate evaluation of the parameter mid-thigh pain would have been possible if we had graded this with a visual analog scale instead of the subjective phrase options that we used. Since the Bonferroni correction used in analysis of the endpoints was not pre-specified in our sample size calculation, it is possible that our study was underpowered. Thus, the outcome of the study can be interpreted as hypothesis-generating.

Conclusion

Up to 2 years postoperatively, we achieved excellent clinical results, early implant stability, and a reduction in adaptive bone loss with this ultra-short stem. We believe that careful patient selection and meticulous surgical technique have been important contributors to our results.

MS conducted the study with patient inclusion, follow-up examinations, and collection and analysis of all data. He also wrote the manuscript. OS designed the study, supervised data collection, and helped with data analysis and manuscript preparation. OM, TA, HB, TE, and AS also helped with manuscript preparation.

The study was supported by grants from the following foundations: Ulla and Gustaf Ugglas Stiftelse, Åke Wibergs Stiftelse, Loo and Hans Ostermans Stiftelse, the Sven Norén Foundation, the regional agreement on medical training and clinical research (ALF) between Stockholm County Council and Karolinska Institutet, and the DePuy Johnsson and Johnsson Foundation for Clinical Research. DePuy Johnsson and Johnsson and the senior author (OS) signed a standard legal study agreement that economic support was granted unconditionally to perform the study and that DePuy Johnsson and Johnsson would have no influence on the study design, data analysis, or publication.

Notes

- Albanese CV, Santori FS, Pavan L, Learmonth ID, Passariello R. Periprosthetic DXA after total hip arthroplasty with short vs. ultra-short custom-made femoral stems: 37 patients followed for 3 years. Acta Orthop 2009 ;80(3): 291–7.

- Aldinger PR, Breusch SJ, Lukoschek M, Mau H, Ewerbeck V, Thomsen M. A ten- to 15-year follow-up of the cementless spotorno stem. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2003; 85(2): 209–14.

- Alm JJ, Makinen TJ, Lankinen P, Moritz N, Vahlberg T, Aro HT. Female patients with low systemic BMD are prone to bone loss in Gruen zone 7 after cementless total hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthop 2009; 80(5): 531–7.

- Berend KR, Mallory TH, Lombardi AV, Jr., Dodds KL, Adams JB. Tapered cementless femoral stem: difficult to place in varus but performs well in those rare cases. Orthopedics 2007; 30(4): 295–7.

- Bodén H, Salemyr M, Sköldenberg O, Ahl T, Adolphson P. Total hip arthroplasty with an uncemented hydroxyapatite-coated tapered titanium stem: results at a minimum of 10 years’ follow-up in 104 hips. J Orthop Sci 2006; 11(2): 175–9.

- Bourne RB, Rorabeck CH, Patterson JJ, Guerin J. Tapered titanium cementless total hip replacements: a 10- to 13-year followup study. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2001; (393): 112–20.

- Chen H-H, Morrey BF, An K-N, Luo Z-P. Bone remodeling characteristics of a short-stemmed total hip replacement. J Arthroplasty 2009; 24(6): 945–50.

- Dorr LD, Faugere MC, Mackel AM, Gruen TA, Bognar B, Malluche HH. Structural and cellular assessment of bone quality of proximal femur. Bone 1993; 14(3): 231–42.

- Ghera S, Pavan L. The DePuy Proxima hip: a short stem for total hip arthroplasty. Early experience and technical considerations. Hip Int 2009; 19(3): 215–20.

- Gotze C, Ehrenbrink J, Ehrenbrink H. [Is there a bone-preserving bone remodelling in short-stem prosthesis? DEXA analysis with the Nanos total hip arthroplasty]. Z Orthop Unfall 2010; 148(4): 398–405.

- Khalily C, Lester DK. Results of a tapered cementless femoral stem implanted in varus. J Arthroplasty 2002; 17(4): 463–6.

- Kim YH, Oh JH. A comparison of a conventional versus a short, anatomical metaphyseal-fitting cementless femoral stem in the treatment of patients with a fracture of the femoral neck. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2012; 94(6): 774–81.

- Kim YH, Choi Y, Kim JS. Comparison of bone mineral density changes around short, metaphyseal-fitting, and conventional cementless anatomical femoral components. J Arthroplasty 2011a; 26(6): 931–40 e1.

- Kim Y-H, Kim J-S, Park J-W, Joo J-H. Total hip replacement with a short metaphyseal-fitting anatomical cementless femoral component in patients aged 70 years or older. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2011b; 93-B(5): 587–92.

- Kwon MS, Kuskowski M, Mulhall KJ, Macaulay W, Brown TE , Saleh KJ. Does surgical approach affect total hip arthroplasty dislocation rates? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2006; 447: 34–8.

- Kärrholm J. Radiostereometric analysis of early implant migration - a valuable tool to ensure proper introduction of new implants. Acta Orthop 2012; 83(6): 551–2.

- Kärrholm J, Borssen B, Löwenhielm G, Snorrason F. Does early micromotion of femoral stem prostheses matter? 4-7-year stereoradiographic follow-up of 84 cemented prostheses. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1994; 76(6): 912–7.

- Lazarinis S, Mattsson P, Milbrink J, Mallmin H, Hailer NP. A prospective cohort study on the short collum femoris-preserving (CFP) stem using RSA and DXA. Primary stability but no prevention of proximal bone loss in 27 patients followed for 2 years. Acta Orthop 2013; 84(1): 32–9.

- Lerch M, von der Haar-Tran A, Windhagen H, Behrens BA, Wefstaedt P, Stukenborg-Colsman CM. Bone remodelling around the Metha short stem in total hip arthroplasty: a prospective dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry study. Int Orthop 2012; 36(3): 533–8.

- Lindahl H. Epidemiology of periprosthetic femur fracture around a total hip arthroplasty. Injury 2007; 38(6): 651–4.

- McClung MR, Geusens P, Miller PD, Zippel H, Bensen WG, Roux C, et al. Effect of risedronate on the risk of hip fracture in elderly women. Hip Intervention Program Study Group. N Engl J Med 2001; 344(5): 333–40.

- Min BW, Song KS, Bae KC, Cho CH, Kang CH, Kim SY. The effect of stem alignment on results of total hip arthroplasty with a cementless tapered-wedge femoral component. J Arthroplasty 2008; 23(3): 418–23.

- Moore AT. The self-locking metal hip prosthesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1957; 39-A(4): 811–27.

- Mortimer ES, Rosenthall L, Paterson I, Bobyn JD. Effect of rotation on periprosthetic bone mineral measurements in a hip phantom. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1996; (324): 269–74.

- Nishii T, Sugano N, Masuhara K, Shibuya T, Ochi T, Tamura S. Longitudinal evaluation of time related bone remodeling after cementless total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1997; (339): 121–31.

- Rahmy AI, Gosens T, Blake GM, Tonino A, Fogelman I. Periprosthetic bone remodelling of two types of uncemented femoral implant with proximal hydroxyapatite coating: a 3-year follow-up study addressing the influence of prosthesis design and preoperative bone density on periprosthetic bone loss. Osteoporos Int 2004; 15(4): 281–9.

- Renkawitz T, Santori FS, Grifka J, Valverde C, Morlock MM, Learmonth ID. A new short uncemented, proximally fixed anatomic femoral implant with a prominent lateral flare: design rationals and study design of an international clinical trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2008; 9: 147.

- Sanz-Reig J, Lizaur-Utrilla A, Llamas-Merino I, Lopez-Prats F. Cementless total hip arthroplasty using titanium, plasma-sprayed implants: a study with 10 to 15 years of follow-up. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2011; 19(2): 169–73.

- Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ 2010; 340: c332.

- Sköldenberg OG, Boden HS, Salemyr MO, Ahl TE, Adolphson PY. Periprosthetic proximal bone loss after uncemented hip arthroplasty is related to stem size: DXA measurements in 138 patients followed for 2-7 years. Acta Orthop 2006; 77(3): 386–92.

- Sköldenberg OG, Salemyr MO, Boden HS, Ahl TE, Adolphson PY. The effect of weekly risedronate on periprosthetic bone resorption following total hip arthroplasty: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2011; 93(20): 1857–64.

- Søballe K, Hansen ES, B-Rasmussen H, Jørgensen PH, Bunger C. Tissue ingrowth into titanium and hydroxyapatite-coated implants during stable and unstable mechanical conditions. J Orthop Res 1992; 10(2): 285–99.

- Streit MR, Merle C, Clarius M, Aldinger PR. Late peri-prosthetic femoral fracture as a major mode of failure in uncemented primary hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2011; 93(2): 178–83.

- Toth K, Mecs L, Kellermann P. Early experience with the Depuy Proxima short stem in total hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthop Belg 2010; 76(5): 613–8.

- Valstar ER, Gill R, Ryd L, Flivik G, Börlin N, Kärrholm J. Guidelines for standardization of radiostereometry (RSA) of implants. Acta Orthop 2005; 76(4): 563–72.

- Walker PS, Culligan SG, Hua J, Muirhead-Allwood SK, Bentley G. The effect of a lateral flare feature on uncemented hip stems. Hip International 1999; (9): 71–80.