Abstract

Background and purpose — Osseointegrated implants are an alternative for prosthetic attachment in individuals with amputation who are unable to wear a socket. However, the load transmitted through the osseointegrated fixation to the residual tibia and knee joint can be unbearable for those with transtibial amputation and knee arthritis. We report on the feasibility of combining total knee replacement (TKR) with an osseointegrated implant for prosthetic attachment.

Patients and methods — We retrospectively reviewed all 4 cases (aged 38–77 years) of transtibial amputations managed with osseointegration and TKR in 2012–2014. The below-the-knee prosthesis was connected to the tibial base plate of a TKR, enabling the tibial residuum and knee joint to act as weight-sharing structures. A 2-stage procedure involved connecting a standard hinged TKR to custom-made implants and creation of a skin-implant interface. Clinical outcomes were assessed at baseline and after 1–3 years of follow-up using standard measures of health-related quality of life, ambulation, and activity level including the questionnaire for transfemoral amputees (Q-TFA) and the 6-minute walk test.

Results — There were no major complications, and there was 1 case of superficial infection. All patients showed improved clinical outcomes, with a Q-TFA improvement range of 29–52 and a 6-minute walk test improvement range of 37–84 meters.

Interpretation — It is possible to combine TKR with osseointegrated implants.

Socket-related discomfort leads to a significant reduction in the quality of life of individuals with lower limb amputation (CitationDillingham et al. 2001, CitationGholizadeh et al. 2014). Socket-skin interface problems lead to poor fit, diminished proprioception in the amputated limb, lack of rotational control, and reduction of ipsilateral proximal joint movement (CitationLegro et al. 1999, CitationLyon et al. 2000, CitationMeulenbelt et al. 2006).

A direct connection of the prosthetic limb to the bone using osseointegrated implants can address these socket-related problems (Van de CitationMeent et al. 2013, CitationTsikandylakis et al. 2014). Brånemark introduced this surgical procedure in 1995. He adapted osseointegration principles established in dental surgery to the rehabilitation of individuals with transfemoral amputation using a percutaneous bone anchoring implant screwed into the femur (CitationBrånemark et al. 2001). Hip replacement spongiosa surface coating technology has been used to make a chrome cobalt intramedullary press-fit implant (Endo-Exo Prosthesis) allowing larger surface area for osseointegration and faster rehabilitation (CitationStaubach and Grundei 2001). Al Muderis et al. (2015) adapted highly porous plasma-sprayed titanium implants to provide optimum initial press-fit and solid bone ingrowth.

Studies of transfemoral implants have found improved quality of life, prosthetic use, body image, hip range of motion, sitting comfort, and walking ability (Van de CitationMeent et al. 2013, CitationHagberg et al. 2014). For example, substantial improvements in health-related quality of life using the Global component of the questionnaire for transfemoral amputees (Q-TFA)—of 38 points (CitationHagberg et al. 2014) and 24 points (Van de CitationMeent et al. 2013)—have been reported in 2 case series of 51 and 22 patients, respectively.

Similar benefits could be expected for transtibial amputees using osseointegrated implants, as the knee joint could possibly enhance their gait. A study of 39 cases involving upper and lower limb prostheses (CitationTillander et al. 2010) found infections in 7 patients at an average follow-up period of 54 (3–132) months, with no infections reported for 1 tibial implant. At our own center, preliminary evidence of the safety and effectiveness of the tibial impants in 22 transtibial amputees with a minimum of 6 months of follow-up gave results consistent with the published results for transfemoral amputations (CitationKhemka et al. 2015).

Few authors have reported on the safety of this procedure (CitationBrånemark et al. 2014, CitationTsikandylakis et al. 2014). One of the largest studies included 51 patients and reported superficial infections in approximately half of these patients at 2-year follow-up. In that study, the implant was removed in 1 patient due to deep infection and in 3 patients due to aseptic loosening (CitationBrånemark et al. 2014).

Osseointegrated implants are not currently recommended for transtibial amputees with ultra-short residuum. In addition to the practical technical challenges, biomechanical studies have suggested that small bone-implant contact is more likely to increase the risk of loosening (CitationLohr et al. 2000, CitationHenriksen et al. 2003, CitationCarvalho et al. 2012). Osseointegration is also not currently recommended for those suffering from ipsilateral knee osteoarthritis because it is hypothesized that an osseointegrated tibial implant will aggravate arthritic symptoms due to mechanical forces (CitationFrossard et al. 2008).

We describe the surgical procedure and early results of combining a total knee replacement (TKR) with an osseointegrated implant for prosthetic attachment for the first time.

Patients and methods

We retrospectively reviewed all 4 individuals with transtibial amputations who underwent TKR combined with an osseointegrated implant at our center. Eligibility criteria included transtibial amputees presenting with socket-related problems and having arthritis and/or a short residuum (< 40 mm). All 4 patients were treated at a specialized orthopedic osseointegration clinic run by the investigators.

Surgical technique

A 2-stage surgical procedure was performed 4–6 weeks apart, to connect an osseointegrated tibial prosthesis to the cemented tibial base plate of a standard hinged TKR prosthesis, transferring the load directly to the femur and enabling the tibial residuum and the knee joint to act as weight-sharing structures.

Implant design

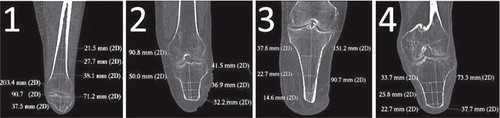

The implant consisted of 4 components. The knee prosthesis used was a standard cemented stemmed rotating hinged-knee system (Genia R-Pol Endoprosthetic Knee System; Orthodynamics GmbH, Lübeck, Germany). The tibial osseointegrated implant component was made of titanium, plasma-sprayed with a rough surface. The dual conus was made from a cobalt-chrome alloy coated with titanium niobium. The fourth component was a cobalt-chrome taper sleeve. The tibial platform and the dual conus were secured to the osseointegrated implant via a locking screw. The implant for each individual patient was designed and customized by the principal investigator based on CT scans and plain radiographs ( and 2; for Figure 2, see Supplementary data)

Surgery stage 1

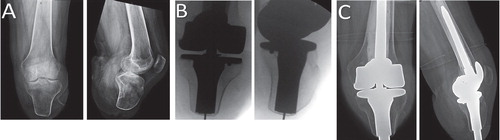

We used spinal anesthesia blockade and 2 g of Cephazolin for infection prophylaxis. The knee was opened in layers using a midline skin incision and a medial peripatellar arthrotomy (CitationCrawford and Coleman 2003). Free-hand tibial plateau resection was done using a sagittal saw. The tibial medullary canal was sequentially broached. The femoral cuts were made using a size-specific block and the medullary canal was reamed for the stem. The trial components were placed in situ and the knee was then taken through a range of motion. An image intensifier was used to check the component position (). Then the definitive components were implanted.

Surgery stage 2

A guide-wire was used to localize the center of the cannulated end-cap using an image intensifier. Passing a coring device over the guide-wire, perforating the skin, subcutaneous tissue, and the sealed end of the bony residuum, a skin-implant interface was created. The skin was then stitched to the bone using intraosseous sutures (2 Nylon). A dual conus was then inserted into the tibial component of the implant followed by a screw locking the 2 components together. This was in turn followed by placing the taper sleeve.

Postoperative care

Wound care involved daily dressing changes with dry ribbon gauze, and sutures were removed after 14 days. This was until the wound granulated over the titanium niobium oxide-polished surface of the dual conus. Thereafter, the patients were instructed to wash the implant-skin interface with warm tap water and soap, and to pat dry.

Rehabilitation

All the patients followed a modified version of the Osseointegration Group of Australia Accelerated Protocol (OGAAP) for postoperative care and rehabilitation, which integrated guidelines for TKR and osseointegration fixations (CitationKhemka et al. 2015).

Patients mobilized without weight bearing using a forearm support frame and assisted by physiotherapists. Knee motion and core strengthening also commenced on day 1.

Following the second stage of rehabilitation involved axial loading of 20 kg twice a day for 20 min, with an increment of 5 kg per day until reaching 50 kg or half of their body weight. Balance and gait training was commenced once the patients were fitted with a prosthesis. They were allowed to mobilize with full weight bearing using 2 crutches for 6 weeks, followed by another 6-week period with a single crutch and unaided thereafter.

Outcomes

Clinical and functional outcomes were measured at baseline and at a minimum of 1 year of follow-up. Plain radiographs were taken at baseline, at 3, 6, and 12 months, and then on an annual basis. Skin-implant interface was monitored, looking at discharge and granulation. Adverse events were monitored.

Functional outcomes were assessed using the physical and mental components of the Short Form 36 (SF-36) health survey as well as the questionnaire for transfemoral amputees (Q-TFA) (CitationWare 1999, CitationHagberg et al. 2004). The Q-TFA was initially developed and validated for use by transfemoral amputees. However, it assesses aspects that are also relevant and meaningful for transtibial amputees: a prosthetic use score (amount of prosthetic wear per week), prosthetic mobility score (prosthetic capability, aids, and habits), problem score (problems related to amputation and prosthesis affecting quality of life), and global score (overall amputation situation). Ambulation ability was assessed at baseline and at 6 and 12 months using the standard “Timed Up and Go” (TUG) and the 6-minute walk test (6MWT). The Amputee Mobility Predictor assessment tool was used to classify mobility, measured as “K-levels”, graded from K-0 (does not have the ability to ambulate) to K-4 (active adult) (CitationGailey et al. 2002). Actual activity level was recorded at baseline and 4 months using a SenseWear (BodyMedia Inc., Pittsburg, PA), which provided the daily average number of steps and also indicators of total and active energy expenditure, and duration of physical activity over a 7-day period of activity (CitationSt-Onge et al. 2007).

Statistics

The differences between follow-up values and baseline values were calculated in measurement units and as a percentage of the baseline value. A Wilcoxon test was used to test for a statistical difference between baseline and follow-up measures. Any p-value of < 0.05 was considered significant. Analyses were conducted using SPSS statistical software.

Ethics

The Human Research Ethics Committee of University of Notre Dame Australia approved the study (ref. no.: 014153S). All the subjects signed an informed consent document.

Results

Patient characteristics

The 4 patients were 3 men and 1 woman aged between 38 and 77 years (). 1 patient was wheelchair-bound and presented with a short residuum (3.8cm). The other 3 patients presented with difficulty walking with their customized socket, even for short distances, and they also had radiographic knee arthritis. These 3 patients suffered from socket interface problems that reduced their personal, recreational, and professional activity level. At the preoperative assessment, the 3 prosthetic users presented with normal posture, walked with an antalgic gait, and had skin breakdown at the distal end of their residuum. All patients complained of phantom limb sensation and pain. Stage 1 of the procedure for all 4 cases occurred between August 2012 and April 2014. Patient follow-up ranged from 12 to 32 months (and 10–30 months after completion of stage 2).

Table 1. Individual and group demographics, amputation information, and rehabilitation timeline

Clinical outcome

All patients had a pain-free knee and no phantom limb sensation at the follow-up assessment. Case 1 reached maximum range of motion of 0–90 degrees, while the others had 0–110 degrees. The implants were stable and well aligned (). All patients had complete healing with no discharge at the 3-month follow-up, and none of the cases presented with granulation tissue (). Only case 3 had 1 episode of superficial infection and a broken bushing (external abutment).

Functional outcome

All patients improved at follow-up for the physical component of SF-36 (score improvement ranged from 1 to 54 points) and the Q-TFA (score improvement range 29–52). Case 1 also showed a marked improvement in the mental function component of SF-36 (Table 2, see Supplementary data).

All cases improved in ambulation and activity levels, although no statistically significant difference was apparent (Table 2). The improvement in daily number of steps ranged from 18% to 730%, and the improvement in duration of physical activity ranged from 18% to 550%. Case 3 remained at level K-3 for mobility (community ambulatory) while cases 1, 2, and 4 improved their ranking by 4, 2, and 2 levels after the procedure to reach the highest K-level (K-4 (active adult)).

Discussion

We report on the feasibility of the first 4 attempts to combine total knee replacement with the tibial osseointegrated implant for prosthetic attachment in transtibial amputees.

A short residuum was defined as < 40 mm, based on the minimum surface area required for osseointegration, which is consistent with other published reports on tibial implants (CitationO’Donnell 2009). Our experience suggests a minority of transtibial amputees are eligible for this procedure. Nevertheless, they are a challenging group to manage and innovative techniques are needed.

A more proximal amputation would be a more straightforward surgical option, but the knee provides much of the power needed for a standard gait cycle (CitationJefferson et al. 1990). Thus, we developed this procedure to offer an important biomechanical advantage over the alternative of a higher-level amputation, such as a knee disarticulation or transfemoral amputation.

In theory, the procedure breaches the conventional principles of joint replacement by exposing the joint to the environment, so careful soft tissue management techniques to reduce the risk of infection are essential. Initial press-fit implantation of the osseointegrated implant is required to provide a proper seal of the implant bone interface. Skin healing at the bone is essential to prevent ascending infection.

There have been too few reports of outcomes of osseointegrated implants for transtibial amputees to compare them with outcomes of conventional socket prostheses. However, observational data indicate that the success of the implantation is related to the length of the residuum, with long residuum giving better results than short residuum in case series (CitationBrånemark et al. 2001). Additionally, osseointegrated implants have not been used in presence of knee joint arthritis. We observed improvement in functional outcomes in our patients. Participants reported being able to use their prosthesis all through the day if needed, which put them at the highest classification level using the Amputee Mobility Predictor tool.

We did not observe any serious adverse events. A superficial infection was treated with a single 7-day course of oral antibiotics (cephalexin 500 mg). The few authors who have reported on the safety of osseointegrated implants have described an acceptable rate of superficial infection and rare occurrence of other adverse events, including deep infection (CitationBrånemark et al. 2014). Altogether, one could hypothesize that the absence of stoma revision and explantation surgeries might be due to techniques adopted to close pathways from the external environment, such as press-fit implantation and soft tissue handling, consequently sealing the knee to ascending infections.

We are concerned about the risk of deep infection associated with this procedure. Given the small sample size, limited follow-up time, and single-clinic setting, larger prospective studies with long-term follow-up will be needed to estimate the risks of infection and benefits of this procedure.

Supplementary data

Figure 2 and Table 2 are available available at Acta’s website (www.actaorthop.org), identification number 8662.

IORT_A_1068635_SM4829.pdf

Download PDF (420.9 KB)AK: data collection, data analysis, and led the writing of the manuscript. LF: figure preparation, table design, and manuscript review. SL: statistical analysis and manuscript review. BB: data collection. MAM: principal surgeon, conception of study, and writing of the manuscript.

MAM currently has financial consultant agreements with Orthodynamics, Endo-Exo Pty Ltd., and Permedica.

- Brånemark R, Brånemark P-I, Rydevik B, Myers R. Osseointegration in skeletal reconstruction and rehabilitation: A review. J Rehabil Res Dev 2001; 38 (2): 175–81.

- Brånemark R, Berlin O, Hagberg K, Bergh P, Gunterberg B, Rydevik B. A novel osseointegrated percutaneous prosthetic system for the treatment of patients with transfemoral amputation: A prospective study of 51 patients. Bone Joint J 2014; 96 (1): 106–13.

- Carvalho JA, Mongon MD, Belangero WD, Livani B. A case series featuring extremely short below-knee stumps. Prosthet Orthot Int 2012; 36 (2): 236–8.

- Crawford JR, Coleman N. Total knee arthroplasty in a below-knee amputee. J Arthroplasty 2003; 18 (5): 662–5.

- Dillingham TR, Pezzin LE, MacKenzie EJ, Burgess AR. Use and satisfaction with prosthetic devices among persons with trauma-related amputations: a long-term outcome study. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2001; 80 (8): 563–71.

- Frossard L, Stevenson N, Smeathers J, Häggström E, Hagberg K, Sullivan J, et al. Monitoring of the load regime applied on the osseointegrated fixation of a transfemoral amputee: a tool for evidence-based practice. Prosthet Orthot Int 2008; 32 (1): 68–78.

- Gailey RS, Roach KE, Applegate EB, Cho B, Cunniffe B, Licht S, et al. The amputee mobility predictor: an instrument to assess determinants of the lower-limb amputee’s ability to ambulate. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2002; 83 (5): 613–27.

- Gholizadeh H, Abu Osman NA, Eshraghi A, Ali S, Razak NA. Transtibial prosthesis suspension systems: systematic review of literature. Clin Biomech (Bristol. Avon) 2014; 29 (1): 87–97.

- Hagberg K, Brånemark R, Hägg O. Questionnaire for Persons with a Transfemoral Amputation (Q-TFA): initial validity and reliability of a new outcome measure. J Rehabil Res Dev 2004; 41 (5): 695–706.

- Hagberg K, Hansson E, Brånemark R. Outcome of percutaneous osseointegrated prostheses for patients with unilateral transfemoral amputation at two-year follow-up. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2014; 95(11): 2120–7.

- Henriksen B, Bavitz B, Kelly B, Harn SD. Evaluation of bone thickness in the anterior hard palate relative to midsagittal orthodontic implants. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2003; 18 (4): 578–81.

- Jefferson RJ, Collins JJ, Whittle MW, Radin EL, O’Connor JJ. The role of the quadriceps in controlling impulsive forces around heel strike. Proc Inst Mech Eng H 1990; 204 (1): 21–8.

- Khemka A, Frossard L, Lord SJ, Bosley B, Al Muderis M. Osseointegrated prosthetic limb for amputees: Over hundred cases. 6th International Conference Advances in Orthopaedic Osseointegration, Las Vegas, United States 26-27 March 2015.

- Legro MW, Reiber G, del Aguila M, Ajax MJ, Boone DA, Larsen JA, et al. Issues of importance reported by persons with lower limb amputations and prostheses. J Rehabil Res Dev 1999; 36 (3): 155–63.

- Lohr J, Gellrich NC, Buscher P, Wahl D, Rahn BA. [Comparative in vitro studies of self-boring and self-tapping screws. Histomorphological and physical-technical studies of bone layers]. Mund Kiefer Gesichtschir 2000; 4 (3): 159–63.

- Lyon CC, Kulkarni J, Zimerson E, Van Ross E, Beck MH. Skin disorders in amputees. J Am Acad Dermatol 2000; 42 (3): 501–7.

- Meulenbelt HE, Dijkstra PU, Jonkman MF, Geertzen JH. Skin problems in lower limb amputees: a systematic review. Disabil Rehabil 2006; 28 (10): 603–8.

- O’Donnell R. Compressive Osseointegration of Tibial Implants in Primary Cancer Reconstruction. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2009; 467 (11): 2807–12.

- St-Onge M, Mignault D, Allison DB, Rabasa-Lhoret R. Evaluation of a portable device to measure daily energy expenditure in free-living adults. Am J Clin Nutr 2007; 85 (3): 742–9.

- Staubach KH, Grundei H. [The first osseointegrated percutaneous prosthesis anchor for above-knee amputees]. Biomed Tech (Berl) 2001; 46 (12): 355–61.

- Tillander J, Hagberg K, Hagberg L, Brånemark R. Osseointegrated titanium implants for limb prostheses attachments: infectious complications. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2010; 468 (10): 2781–8.

- Tsikandylakis G, Berlin O, Brånemark R. Implant survival, adverse events, and bone remodeling of osseointegrated percutaneous implants for transhumeral amputees. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2014: 472(10):2947–56.

- Van de Meent H, Hopman MT, Frolke JP. Walking ability and quality of life in subjects with transfemoral amputation: a comparison of osseointegration with socket prostheses. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2013; 94 (11): 2174–8.

- Ware JEJr, John E, Ware Jr. on health status and quality of life assessment and the next generation of outcomes measurement. Interview by Marcia Stevic and Katie Berry. J Healthc Qual 1999; 21 (5): 12–7.