Abstract

Background and purpose — Virtual reality (VR) simulation offers a safe, controlled, and effective environment to complement training but requires extensive validation before it can be implemented within the curriculum. The main objective was to assess whether VR dynamic hip screw (DHS) simulation has a training effect to improve objective performance metrics.

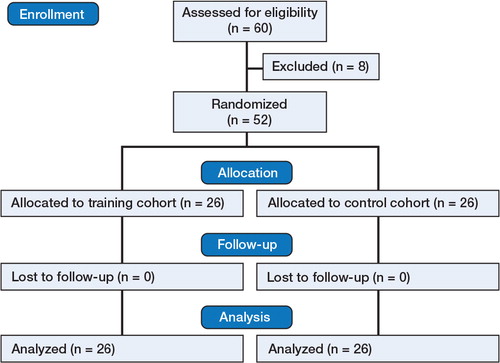

Patients and methods — 52 surgical trainees who were naïve to DHS procedures were randomized to 2 groups: the training group, which had 5 attempts, and the control group, which had only one attempt. After 1 week, both cohorts repeated the same number of attempts. Objective performance metrics included total procedural time (sec), fluoroscopy time (sec), number of radiographs (n), tip-apex distance (TAD; mm), attempts at guide-wire insertion (n), and probability of cut-out (%). Mean scores (with SD) and learning curves were calculated. Significance was set as p < 0.05.

Results — The training group was 68% quicker than the control group, used 75% less fluoroscopy, took 66% fewer radiographs, had 82% less retries at guide-wire insertion, achieved a reduced TAD (by 41%), had lower probability of cut-out (by 85%), and obtained an increased global score (by 63%). All these results were statistically significant (p < 0.001). The participants agreed that the simulator provided a realistic learning environment, they stated that they had enjoyed using the simulator, and they recognized the need for the simulator in formal training.

Interpretation — We found a significant training effect on the VR DHS simulator in improving objective performance metrics of naïve surgical trainees. Patient safety, an important priority, was not compromised.

Orthopedic training in Europe and North America has significantly changed in the past decade due to stricter regulations on working time (CitationPhilibert et al. 2002, CitationNasca et al. 2010). The European Working Time Directive (CitationDepartment of Health 2004) was initially prepared to safeguard both patients and healthcare professionals by promoting risk reduction and increasing patient safety. With trainees taking double the time, on average, per procedure than consultants (CitationBridges and Diamond 1999), opportunities to train in the operating room have decreased substantially to attain greater economic efficiency—with an 80% decrease from the traditionally estimated 30,000 hours to 6,000 hours of experience before these regulations were implemented (CitationChikwe et al. 2004). Simulation offers a risk-free learning environment.

With 1.6 million fractures reported in Europe in the year 2000, osteoporotic fractures accounted for more disability-adjusted life years lost than common cancers with the exception of lung cancer (CitationJohnell and Kanis 2006), and they therefore represent a significant burden of morbidity. A dynamic hip screw (DHS) simulator may provide a means of safely training surgeons to reduce the risk of failure. However, any simulation system requires validation regarding its efficacy and acceptability.

A literature search found only 3 studies using VR models for DHS fixation. CitationBlyth et al. (2007 and Citation2008) reported on a simulator using conventional computer interfaces (mouse and keyboard). CitationFroelich et al. (2011) reported their findings on construct validity of a haptics-enabled simulator using a phantom stylus that had an interface with force feedback. CitationPedersen et al. (2014) demonstrated some degree of construct validity between novices and experienced surgeons looking at 3 orthopedic trauma modules. However, to our knowledge there have not yet been any studies examining the training effect of skills acquisition in orthopedic trauma procedures. Testing of validation involves testing of the training effect with a hypothesis that repeated exposure to the simulator will result in improved objective performance metrics.

Our aim was to validate the training effect of the VR DHS application of the TraumaVision (SveMac, Sweden) simulator, the first commercially available haptic-enabled VR DHS simulator, to determine whether repeated exposure would improve performance metrics in novices naïve to simulation. Primary objectives included real-time measurement of 7 objective performance metrics with learning curves recorded on the VR simulator. Furthermore, this was a hypothesis-generating study since there have been no previous studies to demonstrate either validation or training effects using this particular simulator.

Materials and methods

Simulator equipment

All participants were tested on a TraumaVision VR (SimBones AB, Linkoping, Sweden), a haptics-enabled VR simulator with the additional function of simulated fluoroscopy. The software runs on a standard computer desktop with 2 foot-pedals (to demonstrate anterior-posterior (AP) and lateral fluoroscopic radiography) and a PHANTOM stylus pen (SensAble Technologies Inc., Wilmington, MA).

Participants and logistics

This study took place at the MSk Lab, Imperial College London, between March 22 and May 20, 2014. Data collection from testing took 4 weeks, including the follow-up session. Inclusion criteria included naïvety to DHS procedures and VR simulation in any surgical field, limited to surgical trainees. Exclusion criteria included previous exposure to DHS procedures or orthopedic simulation, limited to postgraduate trainees.

The power calculation was based on a pilot study using surgical trainees with the same inclusion and exclusion criteria. The pilot study consisted of 12 participants who were naïve to simulation. Out of the objective metrics, we determined that at least 20% change was acceptable for the training group. We determined that with a 2-sided α of 0.05 and a power of 80% (ß = 0.2 with largest SD = 211 from the pilot study), we would require at least 32 participants.

52 novice undergraduate surgical trainees were recruited during a mandatory course within the undergraduate orthopedic curriculum, with the option of opting out of the study at any point (as explained when obtaining informed consent). Consequently, selection bias was minimized by avoiding voluntary and self-selected participants. Participants were randomized to either the training cohort or the control cohort via a random number generator using Microsoft Excel, to minimize selection bias. The training group (n = 26) had 5 attempts in week 1, and then 1 week later they had another 5 attempts (10 attempts in total). The members of the control group (n = 26) performed only once on week 1 and they were then retested only once, 1 week later (2 attempts in total). Each participant was blind before entering the study and was tested in isolation to prevent any inter-group and intra-group learning.

52 participants completed the study (). None of them had had any previous exposure to an orthopedic simulator. 35 participants were men, 45 were right-handed, and the median age was 24 years.

Operative tasks

All the participants watched a standardized four-minute instructional video to guide them through the steps of the DHS procedure. They were also guided through the hardware to allow familiarization for 1 min. This included a demonstration of the equipment and explanation of the objective metrics measured using a model DHS construct on the screen.

The standardized task was to perform fixation of an inter-trochanteric fracture, which consisted of 7 steps. Participants were required to manipulate the stylus in 3 dimensions as if it was the drill for placement of a central guide-wire. Reamer and screw length, typically 10 mm less than the depth of the guide-wire, was standardized for participants to ream and place a lag screw. The plate was then placed parallel to the femoral diaphysis and hammered flush with the shaft, followed by insertion of 1 cortical screw distally. The participants were not given any advice or feedback during the procedure. At the end of each procedure, they were given feedback for 1 min on their performance metrics measured by the simulator.

Objective metrics

Primary objectives consisted of 7 objective performance metrics measured by the simulator including (i) total procedural time (sec), (ii) total fluoroscopy time (sec), (iii) number of radiographs taken (n), (iv) tip-apex distance (TAD; mm), (v) number of unique attempts or retries (n) to place the guide-wire, (vi) the probability of cut-out (%) according to Baumgaertner’s graph (CitationBaumgaertner et al. 1995), and (vii) global rating score (n/39) as determined by the simulator according to 17 objective metrics (). A unique attempt was defined as withdrawal of the guide-wire from the cortex proceeded by another attempt to drill. For the training group, the first attempt was compared with the tenth (i.e. last) attempt. For the control group, the first attempt was compared with the second (i.e. last) attempt. Comparing groups, the last attempt for the training group and that for the control group was compared.

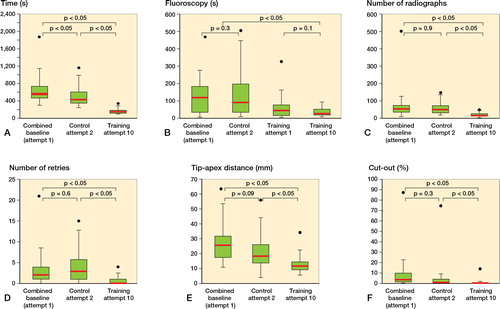

Figure 2. Box and whisker plot showing improvement in metrics in time (s) (A), fluoroscopy (s) (B), number of radiographs (C), number of retries (D), tip-apex distance (mm) (E), and cut-out (%) (F). Dots indicate max outliers. Boxes show the median value (red) and interquartile range (IQR) and whiskers show Q1–1.5×IQR and Q3+1.5×IQR.

Statistics

All objective metrics were recorded as mean (SD). Data are presented in tables, box plots, and scatter graphs for non-parametric, skewed data (confirmed by Kolmogorov-Smirnov test). Analysis was performed using the Wilcoxon signed-ranks test for paired data and the Mann-Whitney U-test was used for independent data. Differences were considered significant when a 2-tailed p-value was less than 0.05. Correlation analysis was performed to assess the interdependence and association between technical metrics and number of attempts.

Ethics

Informed written consent was obtained from every participant.

Results

Time

Comparing cohorts, the training group took 68% less time per procedure than the control group (p < 0.001). The training and control groups showed an improvement in procedure time of 75% (p < 0.001) and of 23% (p = 0.005), respectively ().

Fluoroscopy used

No statistically significant changes were seen in the training group for fluoroscopy (49% decrease), as well as for the control group (22% increase). Comparing groups, the training group used 75% less fluoroscopy than the control group (p < 0.001; ).

Number of radiographs

The training group showed a decrease (by 75%) in the number of radiographs taken (p < 0.001). The control group, however, showed similar numbers between weeks 1 and 2. Comparing groups, the training group took 66% less radiographs than the training group (p < 0.001; ).

Number of retries

The training group showed a decrease (by 68%) in number of retries in inserting the guide-wire (p < 0.001). The control showed a change of 5%, which was not statistically significant. The training group had 82% fewer retries than the control group ().

Tip-apex distance

The training group showed an improvement (by 53%) in TAD (p < 0.001). The control group also showed an improvement (by 21%), which was not statistically significant. Between groups, the training group outperformed the control group, reducing TAD by 41% (p < 0.001; ).

Probability of failure

The training group outperformed the control group in failure (cut-out) probability, reducing the probability of failure by 88% (p < 0.001; ). While the training group showed an improvement (by 85%) in the probability of failure (p < 0.001), the control group did not (50%).

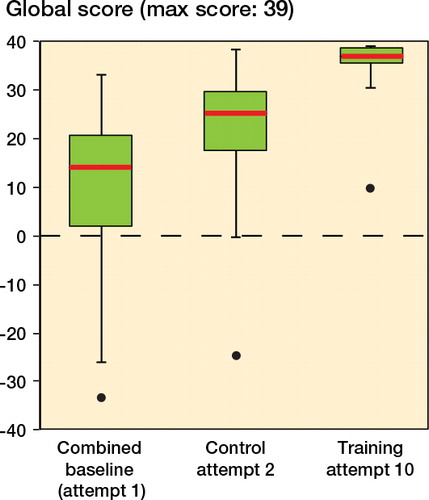

Global score (maximum: 39)

The training group and the control group showed an increase in their global scores (132% and 152%, respectively; both p = 0.001). Comparing groups, the training group outperformed the control, improving its global score by 63% (p < 0.001; )

Summary of results for objective metrics

A correlation was established between the extent of exposure to the VR DHS simulator and objective performance metrics. This is the first time a training effect () has been demonstrated in this hypothesis-generating study.

Table 1. Comparison of metrics for training and control groups before and after training. Values are mean (SD)

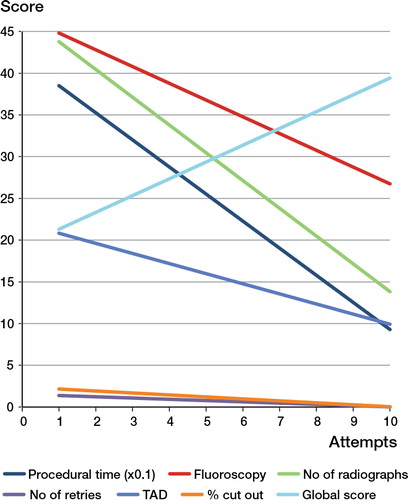

Learning curves

Learning curves in the form of scatter graphs were plotted to show improvement in metrics per attempt (). Participants in the training group showed an improvement across metrics with moderate to strong positive correlation for the metrics in , which lists correlation coefficients and coefficients of determination. The correlation coefficients of 0.73 and higher indicate a strong correlation between number of attempts and technical metrics. Since the coefficient of correlation is at least 0.53, it could reflect on the polynomial degree required for the trendline. However, a linear trendline was optimal for this study to declare a correlation.

Table 2. Correlation coefficients and coefficients of determination for all objective metrics

Discussion

We found a substantial difference in the procedure time, fluoroscopy, number of radiographs, number of retries, TAD, cut-out, and global score within and between cohorts, with the training group showing more improvement than the control group. These findings suggest that a VR DHS simulator has the potential to be implemented within a formal training curriculum.

The improvements indicated mastery of 3 elements: (i) a cognitive improvement in decision-making to attain an optimal instrument position, (ii) an increased visuo-spatial awareness and ability to use 2D images to position a prosthesis accurately in 3 dimensions, and (iii) a psychomotor control with the capacity to precisely manipulate instruments. Orthopedic simulation is conducted in a controlled environment without posing any risk to patient safety or any risk from occupational hazards such as fluoroscopic radiation. Trainees can also improve their skills (for instance, hand-eye coordination, manual dexterity, and triangulation). Simulators are viable since they can be reused and used outside the time of clinical duty.

As training progressed, the training cohort became increasingly aware of the importance of the initial starting point, the guide-wire trajectory, and the subsequent screw positioning. Although the participants used less radiographs, they compromised by using more fluoroscopy to attain a more accurate TAD. The participants were not aware of the clinical significance of TAD initially, but with practice they understood its importance with respect to failure rate and structural integrity.

In the control group, a statistically significant improvement in time and global score was found. We believe that this reflects increased familiarity with the interface. The control group became comfortable with manipulating the PHANTOM stylus pen at the first attempt, and found that they could concentrate more on the VR task at the second attempt—to score higher.

Significance of improvement

In clinical practice, a malaligned DHS results in a greater risk of cut-out, dislocation, and post-traumatic osteoarthritis, inflicting significant morbidity and disability on patients. TAD is the only validated clinical outcome that was measured (CitationBaumgaertner et al. 1995, CitationGüven et al. 2010, CitationHsueh et al. 2010, CitationAndruszkow et al. 2012). CitationBaumgaertner et al. (1995) demonstrated that a TAD of less than 25 mm was the most important factor to minimize the cut-out rate. The control group showed a small improvement in TAD, from 20 mm to 18 mm, which is likely to reflect a learning curve, established in using the simulator rather than with the clinical procedure. On the other hand, the training group showed a significant improvement in TAD, from 26 mm to 11 mm.

There is a correlation between cut-out and failure rate, which can result in revision surgery. Baumgaertner’s graph predicts failure rates (CitationBaumgaertner et al. 1995). Their training group had an improvement of 94% down to a cut-out rate of 0.2%, while the control group improved by 16% down to an overall cut-out rate of 1.2%.

Improvement in procedural time would result in a shorter operating time. This time difference could theoretically correlate with a shorter operation with a more precise DHS placement, as demonstrated by the training group, to improve patient outcomes. Additionally, the training group used less fluoroscopy—which could translate clinically into less ionizing radiation and less associated risk. This outcome is also in keeping with the study by Van CitationHerzeele et al. (2008), which looked into improved fluoroscopic usage in VR carotid artery stenting with practice. The reduced number of attempts at inserting the guide-wire would reduce surgically-induced trauma and inflammation, to speed up recovery.

We found an improvement in the learning curves for all objective metrics, with a moderate to strong correlation. There was an increase in time between attempts 5 and 6 in the training group, in which participants had a 1-week interval, indicating decay in skills—but with an improved baseline for skill acquisition recall. The participants returned to their previous optimal performance levels by the seventh attempt, and then continued to improve further.

Comparison with the current literature

Several studies have looked at VR simulators for fracture fixation. CitationFroelich et al. (2011) attempted to establish construct validity using TraumaVision by examining 2 cohorts: postgraduate years 1–3 (PGY 1–3) and postgraduate years 3–5 (PGY3–5). However, they did not find any statistically significant difference in TAD and time taken between cohorts, probably due to low power.

When testing, CitationFroelich et al. (2011) only allowed participants 6 attempts. As shown by the linear correlation analysis, 6 attempts caused an improvement in all metrics. Thus, multiple attempts would result in an improvement in the PGY1–2 cohort, minimizing the difference between cohorts. This is most likely the reason for CitationFroelich et al. (2011) not finding a statistically significant difference in time taken and TAD. Furthermore, CitationPedersen et al. (2014) allowed novice and experienced participants each to have a 20-min warm-up time but did not focus on the training or learning effect in mastering the 3 orthopedic trauma modules.

Another independent variable that has been identified to correlate with VR simulator performance is exposure to video-gaming. With modern generations of orthopedic trainees being exposed to virtual reality worlds and video-gaming, we recently demonstrated that there was no correlation between video-gaming experience and gaining of competency on a VR DHS simulator (CitationKhatri et al. 2014), which is contrary to the current literature on general surgical simulators (CitationRosenberg et al. 2005, CitationRosser et al. 2007, CitationBadurdeen et al. 2010, CitationRosser et al. 2012, CitationGiannotti et al. 2013).

Limitations

This study did not correlate visuo-spatial and psychomotor ability with performance on the VR DHS simulator. However, we do not believe that it would have drastically affected the results, as seen in . Also, the simulator could only visualize a left-sided hip, irrespective of hand dominance, but the stylus pen could be manipulated easily with the dominant hand.

Future prospects

Orthopedic VR simulators may help to identify, reduce, and prevent errors in practice. The incorporation of VR simulators in training regimes offers the potential to reduce error rate which, as well as improving patient outcomes and satisfaction, will also reduce fiscal burden by decreasing the risk of litigation. CitationSeymour et al. (2002) showed skills transfer from training on a simulator to the operating theater, and this has been emulated by other studies (CitationAhlberg et al. 2007, CitationVerdaasdonk et al. 2008, CitationLarsen et al. 2009) including 1 with an orthopedic arthroscopic simulator (CitationHowells et al. 2008). Other factors to consider include gender differences, hand dominance, and age correlated with objective scoring.

Conclusion

Undergraduate surgical trainees naïve to orthopedic surgery and simulation showed clinically relevant improvements in objective metrics using a VR haptics-enabled DHS simulator. The simulator is acceptable as a realistic representation of the operation. The participants enjoyed and recognized a need for the simulator in formal training. Basic surgical skills and competency can be acquired in a controlled environment without compromising patient safety.

Planning and design of the study: KS, KA, and CM. Hypothesis: KS and KA. Statistical analysis: CK and KS. Writing of the manuscript: CK, KS, KA, JC, and CG. All the authors revised and approved the final manuscript.

There was no external funding of the study. It was performed completely independently of the simulator company. There are no competing interests.

- Ahlberg G, Enochsson L, Gallagher AG, Hedman L, Hogman C, McClusky DA3rd, Ramel S, Smith CD, Arvidsson D. Proficiency-based virtual reality training significantly reduces the error rate for residents during their first 10 laparoscopic cholecystectomies. Am J Surg 2007; 193 (6): 797–804.

- Andruszkow H, Frink M, Frömke C, Matityahu A, Zeckey C, Mommsen P, Suntardjo S, Krettek C, Hildebrand F. Tip apex distance, hip screw placement, and neck shaft angle as potential risk factors for cut-out failure of hip screws after surgical treatment of intertrochanteric fractures. Int Orthop 2012; 36 (11): 2347–54.

- Badurdeen S, Abdul-Samad O, Story G, Wilson C, Down S, Harris A. Nintendo Wii video-gaming ability predicts laparoscopic skill. Surg Endosc 2010; 24 (8): 1824–8.

- Baumgaertner MR, Curtin SL, Lindskog DM, Keggi JM. The value of the tip-apex distance in predicting failure of fixation of peritrochanteric fractures of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1995; 77 (7): 1058–64.

- Blyth P, Stott NS, Anderson I. A simulation-based training system for hip fracture fixation for use within the hospital environment. Injury 2007; 38 (10): 1197–203.

- Blyth P, Stott NS, Anderson I. Virtual reality assessment of technical skill using the Bonedoc DHS simulator. Injury 2008; 39 (10): 1127–33.

- Bridges M, Diamond DL. The financial impact of teaching surgical residents in the operating room. Am J Surg 1999; 177 (1): 28–32.

- Chikwe J, de Souza AC, Pepper JR. No time to train the surgeons. BMJ 2004; 328 (7437): 418–9.

- Department of Health. Guidance on the implementation of the European Working Time Directive. 2004; (July). Available at: http://www.dohc.ie/issues/european_working_time_directive/. Accessed July 18 2014.

- Froelich JM, Milbrandt JC, Novicoff WM, Saleh KJ, Allan DG. Surgical simulators and hip fractures: a role in residency training? J Surg Educ 2011; 68 (4): 298–302.

- Giannotti D, Patrizi G, Di Rocco G, Vestri AR, Semproni CP, Fiengo L, Pontone S, Palazzini G, Redler A. Play to become a surgeon: impact of Nintendo Wii training on laparoscopic skills. PLoS One 2013; 8(2): e57372.

- Güven M, Yavuz U, Kadioglu B, Akman B, Kilinçoglu V, Unay K, Altintas F. Importance of screw position in intertrochanteric femoral fractures treated by dynamic hip screw. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2010; 96 (1): 21–27.

- Hsueh K-K, Fang C-K, Chen C-M, Su Y-P, Wu H-F, Chiu F-Y. Risk factors in cutout of sliding hip screw in intertrochanteric fractures: an evaluation of 937 patients. Int Orthop 2010; 34 (8): 1273–6.

- Howells NR, Gill HS, Carr J, Price J, Rees JL. Transferring simulated arthroscopic skills to the operating theatre: a randomised blinded study. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2008; 90 (4): 494–9.

- Johnell O, Kanis J. An estimate of the worldwide prevalence and disability associated with osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int 2006; 17 (12): 1726–33.

- Khatri C, Sugand K, Anjum S, Vivekanantham S, Akhtar K, Gupte C. Does video gaming affect orthopaedic skills acquisition? A prospective cohort-study. PLoS One. 2014; 9(10): e110212.

- Larsen CR, Soerensen JL, Grantcharov TP, Dalsgaard T, Schouenborg L, Ottosen C, Schroeder TV, Ottesen BS. Effect of virtual reality training on laparoscopic surgery: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2009; 338: b1802.

- Nasca TJ, Day SH, Amis ES. The new recommendations on duty hours from the ACGME Task Force. N Engl J Med 2010; 363 (2): e3.

- Pedersen P, Palm H, Ringsted C, Konge L. Virtual-reality simulation to assess performance in hip fracture surgery. Acta Orthop 2014; 85 (4): 403–7.

- Philibert I, Friedmann P, Williams WT. New requirements for resident duty hours. JAMA 2002; 288 (9): 1112–4.

- Rosenberg BH, Landsittel D, Averch TD. Can video games be used to predict or improve laparoscopic skills? J Endourol 2005; 19 (3): 372–6.

- Rosser JCJr, Lynch PJ, Cuddihy L, Gentile DA, Klonsky J, Merrell R. The impact of video games on training surgeons in the 21st century. Arch Surg 2007; 142 (2): 181–6; discusssion 186.

- Rosser J C Jr, Gentile DA, Hanigan K, Danner OK. The effect of video game “warm-up” on performance of laparoscopic surgery tasks. JSLS 2012; 16 (1): 3–9.

- Seymour NE, Gallagher AG, Roman SA, O’Brien MK, Bansal VK, Andersen DK, Satava RM. Virtual reality training improves operating room performance: results of a randomized, double-blinded study. Ann Surg 2002; 236 (4): 458–63; discussion 463–4.

- Van Herzeele I, Aggarwal R, Neequaye S, Hamady M, Cleveland T, Darzi A, Cheshire N, Gaines P. Experienced endovascular interventionalists objectively improve their skills by attending carotid artery stent training courses. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2008; 35 (5): 541–50.

- Verdaasdonk E GG, Dankelman J, Lange JF, Stassen L PS. Transfer validity of laparoscopic knot-tying training on a VR simulator to a realistic environment: a randomized controlled trial. Surg Endosc 2008; 22 (7): 1636–42.