Abstract

Background and purpose — There have recently been highly publicized examples of suboptimal outcomes with some newer implant designs used for total hip replacement. This has led to calls for tighter regulation. However, surgeons do not always adhere to the regulations already in place and often use implants from different manufacturers together to replace a hip, which is against the recommendations of the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) and the directions of the manufacturers.

Patients and methods — We used data from the National Joint Registry of England and Wales (NJR) to investigate this practice.

Results — Mixing of components was common, and we identified over 90,000 cases recorded between 2003 and 2013. In the majority of these cases (48,156), stems and heads from one manufacturer were mixed with polyethylene cemented cups from another manufacturer. When using a cemented stem and a polyethylene cup, mixing of stems from one manufacturer with cups from another was associated with a lower revision rate. At 8 years, the cumulative percentage of revisions was 1.9% (95% CI: 1.7–2.1) in the mixed group as compared to 2.4% (2.3–2.5) in the matched group (p = 0.001). Mixing of heads from one manufacturer with stems from another was associated with a higher revision rate (p < 0.001). In hip replacements with ceramic-on-ceramic or metal-on-metal bearings, mixing of stems, heads, and cups from different manufacturers was associated with similar revision rates (p > 0.05).

Interpretation — Mixing of components from different manufacturers is a common practice, despite the fact that it goes against regulatory guidance. However, it is not associated with increased revision rates unless heads and stems from different manufacturers are used together.

Total hip replacement (THR) has become the standard treatment for end-stage arthritis of the hip, and it is used in a significant proportion of patients with a subcapital fracture of the femoral neck.

The majority of manufacturers stipulate in their “instructions for use” that surgeons should use all the components from the same manufacturer, otherwise the surgeons will be working “off label”. However, many surgeons in the UK have matched a femoral component from one manufacturer with an acetabular component from another manufacturer. The surgeons who do this are encouraged by the excellent results that can be achieved following this practice—results that are at least comparable to those obtained when mixing and matching has not been performed. This group of excellent results has usually involved a metal or ceramic head on a polyethylene acetabular component. For example, the NJR 10th Annual Report recorded that between 2003 and 2011 over 6,000 Exeter V40 stems (manufactured by Stryker) were implanted with Elite plus polyethylene cups (manufactured by DePuy), with excellent implant survivorship. In 2013, 11,496 out of 78,479 hip replacements undertaken in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland were “mixed”, i.e. components from different manufacturers were used together. In all, 820 different combinations of stems and cups were used, out of which 487 different combinations were mixed.

Recently, the practice of mixing and matching has again come under close scrutiny with the use of large-head “metal-on-metal” devices (LHMOM), where both the femoral head and the acetabular components are made of metal (Telegraph 2014). It is known that LHMOM is associated with a high implant failure rate (CitationSmith et al. 2012), and not only has the bearing surface come under scrutiny but also the “taper junction” where the tapered trunnion of the neck of the femoral implant engages the modular femoral head (CitationNassif et al. 2014). It has been shown that poorly fitting femoral heads will lead to increased fretting and wear at the taper junction, which has been suggested as a cause for early failure of LHMOM implants (CitationDonaldson et al. 2014, CitationBolland et al. 2011). It is logical to assume that when components that are made by different manufacturers—with different tolerances and designs—are used together, the fretting will be worse.

We investigated the practice of “mixing and matching” of components from different manufacturers in total hip replacement in England and Wales using data from the National Joint Registry. Our hypothesis was that the mixing and matching of components from different manufacturers in primary THR would lead to higher implant revision rates.

Material and methods

The National Joint Registry of England and Wales has been recording total hip replacements since April 1, 2003. As part of a routine search for “outlying” implants, data sets are “cut” twice a year for further scrutiny, with all primary operations entered since the start of the registry up to the “cut-point” date included. This report describes a data set cut on September 6, 2013.

Our analysis focused specifically on the 5 main groups of hip procedures, the first 2 of which were “hard-on-soft” and the rest “hard-on-hard”. These were (1) a cemented stem (modular or monobloc), used together with a polyethylene monobloc acetabulum, or modular stems (both cemented and uncemented) used specifically with (2) a metal shell with a polyethylene liner (including a pre-assembled shell/liner), or (3) a metal shell with a metal liner or an all-metal acetabulum (but excluding resurfacing cups), (4) a metal shell with a ceramic liner, or (5) a resurfacing cup used with a metal head.

Further subdivisions were made by component composition and fixation, as deemed appropriate to the analysis:

In group (1), we looked for mixing of manufacturers of the stems and cups and then, in separate analysis of just the modular stems, we looked at mixing of head and stem. In the latter, the heads were either metal or ceramic, but mostly the former.

Polyethylene cups in group (1) were always cemented. Group (2), (3), and (4) metal cups/shells were normally uncemented whereas their stems (which included modular heads, distal/proximal stems, and modular necks) may have been (i) cemented or (ii) uncemented, and these were analyzed separately. In group (2), either metal or ceramic heads were used. Group (3) mostly had metal heads; the few ceramic heads are reported separately. Group (4) heads were predominately ceramic, and only these are discussed.

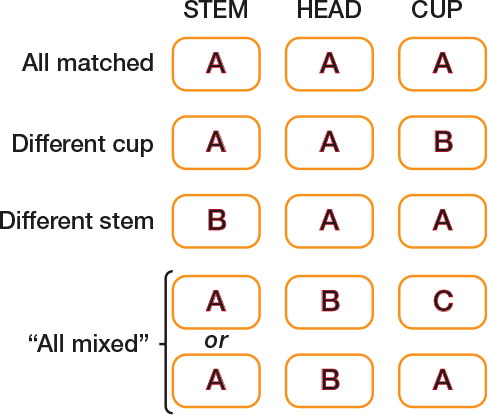

In groups (2) and (3), we looked at mixing of stem and head as well as head and cup. We defined 4 subgroups for comparison, which are shown diagrammatically in , namely “All matched” (i.e. stem, head, and cup made by the same manufacturer), “Different cup” (stem and head made by the same manufacturer but cup made by a different manufacturer, thus mixing only head and cup), “Different stem” (head and cup made by the same manufacturer but stem made by a different manufacturer, thus mixing only stem and head), and “All mixed” (stem and head were made by different manufacturers and the head and cup were made by different manufacturers). Note, however, that this last group did include some cases in which the stem and cup were made by the same manufacturer (as in the bottom row of ).

Figure 1. Diagram to show mixing of stem, head, and cup components between different manufacturers (modular stems only), where A, B, and C are manufacturers

In group (4), we looked only at mixing with respect to head and cup.

In group (5), we again split the stems into (i) cemented and (ii) uncemented, as for (2)–(4), and looked at mixing of stem, head and cup (as in ).

Statistics

Statistical survival analyses were used to compare mix-and-match subgroups with respect to their implant survivorship, i.e. the need for a subsequent revision, censoring at September 6, 2013 or at the date of the patient’s death if that was earlier. Cumulative percentages of revision were estimated using Kaplan-Meier curves and the curves for the subgroups were compared using log-rank tests. The age and sex distributions of the subgroups were summarized. Given that revision rates were known to differ between men and women and to vary differently with age in men and women, adjustment for age and sex was made by stratifying the data into 7 × 2 = 14 age-sex subgroups (age < 55, 55–59, 60–64, 65–69, 70–74, 75–79, and ≥ 80 years for each sex) and performing stratified log-rank tests. The log-rank test compares the observed numbers of revisions (O) with the numbers expected (E) if the subgroups were to have the same underlying revision rates; in stratified analyses, the expected numbers were calculated separately within each stratum and summed (CitationAltman 1991). Subgroups with higher revision rates are those with higher O:E ratios. They would also be expected to have higher patient-time incidence rates (PTIRs), which were also calculated, but they do not take sex/age differences into account.

In order to match our groups as closely as possible, where group sizes were sufficiently large, we extended our analyses by looking at specific brands, for example focusing on a commonly used stem brand together with cup(s) made by the same manufacturer or cup(s) made by different manufacturers.

All statistical analysis used the software package Stata version 13.1. A 5% level of significance was used throughout.

Results

Hard-on-soft bearings

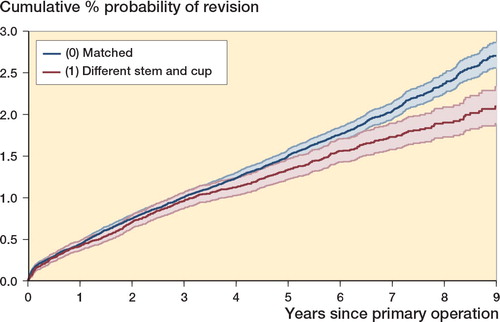

(1) Cemented modular stem, or a monobloc stem, used in combination with a polyethylene cemented cup. and document the implant survivorship of 206,334 hip replacements consisting of a cemented femoral stem (a metal monobloc stem or a metal stem with a metal or ceramic head) in combination with a cemented polyethylene cup.

Table 1. Mixed stem and cup manufacturers in cemented modular stem, or monobloc stem, used with a polyethylene cemented cup

Figure 2. Effect of stem and cup manufacturer mismatch on revision of cemented modular stem or monobloc stem used with a polyethylene cemented cup. Kaplan-Meier estimates of cumulative % probability of revision. Shaded bands indicate point-wise 95% CI.

The overall implant survivorship was better in the mixed group than in the matched group (p = 0.001; p = 0.001 with age/sex stratification). This is illustrated in and in , where mixed cases had fewer revisions than expected. At 8 years, the cumulative percentage of revisions was 1.9% (95% CI: 1.7–2.1) in the mixed group and 2.4% (2.3–2.5) in the matched group.

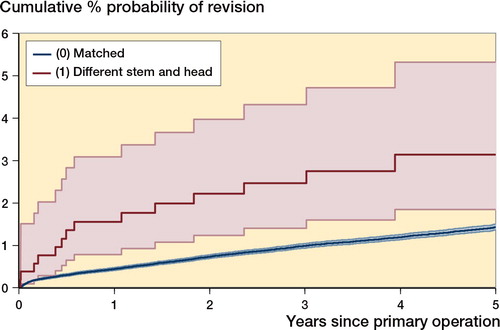

Among the 183,523 cemented modular stems in group (1), we further compared 527 cases where the stem and head were mixed (i.e. were from different manufacturers) with 180,778 cases where the stem and head were matched (Table 2, see Supplementary data, and ). Using a head from a different manufacturer was associated with significantly higher failure rates than using a stem and head from the same manufacturer (p < 0.001; stratified p < 0.001). has been truncated at 5 years, at which point the number at risk in the smaller group fell below 150.

Figure 3. Effect of stem and head manufacturer mismatch on revision of cemented modular stem used with cemented polyethylene cup. Kaplan-Meier estimates of cumulative % probability of revision. Shaded bands indicate point-wise 95% CI.

(2) Modular stems used with an uncemented metal shell with a polyethylene liner. Implant survivorship of this group is documented in . Cemented and uncemented stems have been analyzed separately, looking for mixing of stem, head, and cup components in each case (see ). Parallel results for ceramic heads are available on request.

(together with Tables 5 and ) is referenced to the head manufacturer. For example, in , of the 60,167 cases with a cemented stem together with a metal head, 35,588 cases (59.1%) had stem, head, and cup made by the same manufacturer (matched). In 24,004 cases (39.9%), the head and stem were from one manufacturer and the cup was from another. In 136 cases (0.2%), the head and cup were from one manufacturer but the stem was from another manufacturer, and in 439 cases (0.7%), the stem and head and cup were mixed.

Table 3. Mixed stem, head, and cup manufacturers in modular stems with a metal head and a metal shell with a polyethylene liner

In this group, there were differences between the 4 groups after age-sex adjustment (p = 0.07, log-rank test; p = 0.04 with age/gender stratification). Implant survivorship was not significantly different between the matched cases and the mixed cases where only the cup manufacturer was different (p = 0.5), but it was markedly worse in the 2 groups where the stem and head were from different manufacturers.

When an uncemented stem was used, there was similar implant survivorship between the subgroups overall (p = 1.0; stratified p = 0.9).

In order to match our groups as closely as possible, we compared a subgroup of 29,003 hip replacements where a cemented Exeter V40 stem (manufactured by Stryker) was used with metal head in all cases either combined with a matched uncemented cup (Trident) or mixed cups (Duraloc or Pinnacle, both manufactured by DePuy, or Trilogy, manufactured by Zimmer). Results are shown in Table 4 (I) (see Supplementary data). There was no statistically significance difference between the various combinations overall (p = 0.6; stratified p = 0.5)

We then compared a subgroup of 32,629 hip replacements where an uncemented Corail stem (manufactured by DePuy) and metal head were used in all cases; either combined with “matched” cups (Duraloc or Pinnacle) or “unmatched” cups (Trilogy, manufactured by Zimmer) (Table 4 (II), see Supplementary data). There was no overall statistically significant difference in implant survivorship between the groups (p = 0.08; stratified p = 0.06).

Parallel results for ceramic, rather than metal, heads are not shown, but are available on request. There were no statistically significant differences between the matched group and the subgroups with different cups (p = 0.1 and p = 0.3, respectively, for cemented and uncemented stems), but other groups were too small for meaningful analysis.

Hard-on-hard bearings

(3) A metal shell with a metal liner or an all-metal acetabulum (but excluding resurfacing cups). Cemented and uncemented stems were analyzed separately, in each case looking for mixing of stem, head, and cup components ().

The combination of a cemented stem with a metal head, metal cup, and metal liner was rarely employed—with only 1,382 cases—so the data are not shown but are available on request.

Results for the 15,913 cases with uncemented stems are shown in Table 5 (see Supplementary data). There were few mix-and-match cases in this group, so we have simply tabulated numbers of revisions, patient-years at risk, and the PTIRs.

(4) A metal shell with a ceramic liner. documents the implant survivorship of hip replacements consisting of a femoral stem used with a ceramic head and a metal shell with a ceramic liner. Cemented and uncemented stems are shown separately.

Table 6. The mixing of head and cup manufacturers in modular stems using a ceramic head and a metal shell with a ceramic liner

There were no statistically significant differences in implant survivorship when using either a cemented stem (p = 0.063, stratified p = 0.057) or an uncemented stem (p = 0.9; stratified p = 1.0).

In order to match our groups as closely as possible, we compared a subgroup where a cemented Exeter V40 stem (manufactured by Stryker) and a ceramic head were used in all cases: either combined with matched cups or with unmatched cups (Exceed cups made by Biomet, or Trilogy cups made by Zimmer (Table 7 (I), see Supplementary data)). Failure rates were very low in all groups and there was similar outcome (p = 0.4; stratified p = 0.4).

We compared a subgroup where an uncemented Corail stem (manufactured by DePuy) was used with a ceramic head in all cases—either combined with matched cups (Duraloc or Pinnacle) or unmatched cups (Trinity, manufactured by Corin; CSF Plus, manufactured by JRI; or Delta TT, manufactured by Lima) (Table 7 (II), see Supplementary data). There was similar implant survivorship between the groups (p = 0.8; stratified p = 0.8).

(5) Metal heads used with a metal monobloc cup designed for use in hip resurfacing. Results are shown separately for cemented and uncemented stems in . Summary statistics for head size have been added, as this is known to correlate strongly with revision rates in metal-on-metal total hip replacements (CitationSmith et al. 2012).

Table 8. Mixed stem, head, and cup in modular stems with metal heads used with a metal monobloc cup designed for use in hip resurfacing

When using a cemented stem, the implant survival in the group with a “different stem” appeared worse than the “all matched” group, but the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.06; stratified p = 0.2).

When using an uncemented stem, the “all matched” group had a higher revision rate than the group with a different head and stem (p < 0.001; stratified p < 0.001). The head sizes were similar between these 2 groups (p = 0.4, Mann-Whitney U-test with adjustment for ties).

We repeated the last analysis, excluding the ASR resurfacing cup, as this had been shown to have an unusually high failure rate (CitationLangton et al. 2011) and has subsequently been withdrawn (). With the ASR excluded, the difference in revision rates was no longer significant (p = 0.9; stratified p = 1.0).

Discussion

The use of total hip replacement implants is not tightly regulated—thereby allowing rapid innovation, but also increasing the risk of introducing new problems. Recent publications have highlighted the need for tighter implant regulation and surveillance (CitationSedrakyan 2012, CitationCohen 2012) following the failures associated with metal-on-metal articulations (CitationSmith et al. 2012).

Surgeons in England and Wales often mix components from different manufacturers, despite this being against manufacturers’ guidelines and not being endorsed by the MHRA who have written: “The manufacturers state in their Instructions for Use that their components should not be used with those of other manufacturers. The regulators expect that hip replacements are used in accordance with the manufacturer’s “Instructions for Use” and it should be noted that the safety of mixed and matched combinations has not been assessed. Therefore, surgeons implanting not approved mixed and matched combinations do so under their own liability.” (MHRA on-line, accessed 2014).

We have shown that it is particularly common to mix metal heads from one manufacturer with polyethylene cups from another manufacturer. Surprisingly, this has been associated with lower implant revision rates. However, in hard-on-soft bearings, when mixing metal heads from one manufacturer with stems from another manufacturer, the revision rates were worse than with matched combinations. A possible mechanism for this could be mechanical corrosion at the taper junction (CitationPanagiotidou et al. 2013) and, while accepting that this has been well described in matched prostheses, the question is whether it may be more likely to occur in unmatched combinations. This occurs in matched large-head metal-on-metal implants and metal-on-polythene bearings (CitationCooper et al. 2012).

Modular implants are attached by a Morse taper that is reciprocal on the trunnion and the femoral head. Many different dimensions are used and are described by measurements in millimetres, taken from the apex and the base of the trunnion; 12/14 is the commonest in current usage. There is, however, a third critical measurement that determines the geometry, the length of the trunion, resulting in a wide range of shapes within the 12/14 subset of taper designs and few are compatible. This has been widely recognized for many years, but the apparent closeness of the designs leads some to ignore the potential problems (AAOS on-line).

Furthermore, the surface finish on both sides of the taper differs between manufacturers, which can increase the problems generated by any geometric incompatibility.

Mixing of hard-on-hard bearing surfaces from different manufacturers did not appear to be associated with either higher or lower revision rates. These components are manufactured with tight tolerances, and a perfectly round femoral head of a certain diameter from one manufacturer should have the same outer dimensions as one from another manufacturer. Almost all ceramic bearings are manufactured for the implant companies by the same manufacturer.

It can be argued that as it is not necessary to mix and match hard-on-hard bearing surfaces in the primary hip replacement setting and as mixed hard-on-hard bearing surfaces do not confer an advantage, the practice should be discouraged. However, in the revision setting, often only one component has failed and needs to be replaced and no matched component is available. The surgeon is then faced with a choice of either mixing components from different manufacturers or revising a well-functioning component with the associated trauma, blood loss, and prolonged operating time. It is therefore encouraging that our data suggest that using hard-on-hard bearings from different manufacturers is not associated with higher revision rates, albeit in the primary setting.

It is important to note that individual mix-and-match combinations can still be implant outliers, just as individual matched combinations can be implant outliers. Our data should not be seen as an endorsement of all mix-and-match combinations. For the sake of clarity, we would like to add that the NJR “Implant Performance Committee” has indeed identified some “mix-and-match” combinations as being outliers. This means that their PTIR is more than twice the average of the group. This information has been passed to the MHRA, who have taken up the matter with the appropriate manufacturers. It must also be added that the same process has been followed with a greater number of outlier components where mixing and matching has not taken place.

The strengths of our study include the very large sample sizes in most groups and the length of follow-up. Registry data are comprehensive, and one therefore avoids some of the pitfalls associated with single-center or single-surgeon data, which may not be generalizable. The weaknesses of the study include the fact that registry data are observational and therefore cannot infer causality. Selection bias cannot be discounted, and may partially explain some of the differences. Data are validated against implant sales and correlate strongly (CitationNJR 10th Annual Report). However, NJR audit suggests that there may be selective under-reporting of revisions in some centers. If there is widespread systematic under-reporting of mixed components, then this might alter the findings.

In summary, we have used data from the largest arthroplasty database in the world and shown that in hip replacement surgery in England and Wales, mixing of components from different manufacturers is extremely common despite being contrary to manufacturers’ and MHRA guidelines. This practice is not associated with increased implant revision rates except in certain combinations when heads and femoral stems from different manufactures are used together. The regulatory authorities should be able to use the data presented here for incorporation in any future guidance.

Supplementary data

Tables 2, 4, 5 and 7 are available on the Acta Orthopaedica website at www.actaorthop.org, identification number 8603.

IORT_A_1074483_SM1653.pdf

Download PDF (41.1 KB)All the authors were involved in the design of the study. Data management and analysis were undertaken by LH, KT, MP, and LH, and AB contributed to data interpretation. All the authors contributed to preparation of the manuscript.

Stryker and DePuy have funded other research undertaken by the University of Bristol.

We thank the patients and staff of all the hospitals who have contributed data to the National Joint Registry. We are grateful to the Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership (HQIP), the National Joint Registry Steering Committee (NJRSC), and staff of the NJR Centre for facilitating this work. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NJRSC or HQIP, who do not vouch for how the information is presented.

The sponsor of the study (The National Joint Registry) had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the final report. LH had full access to all the data in the study and AB had final responsibility for the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

- Altman DG. ‘Practical Statistics for Medical Research’, First edition, 1991: pp 365–395, Chapman and Hall, London.

- Bolland BJ, Culliford DJ, Langton DJ, Millington JP, Arden NK, Latham JM. High failure rates with a large-diameter hybrid metal-on-metal total hip replacement: clinical, radiological and retrieval analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2011; 93(5): 608–15.

- Cohen D. How a fake showed up failings in European device regulation. BMJ 2012; 345: e7090.

- Cooper HJ, Della Valle CJ, Berger RA, Tetreault M, Paprosky WG, Sporer SM, Jacobs JJ. Corrosion at the head-neck taper as a cause for adverse local tissue reactions after total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2012; 94(18): 1655–61.

- Donaldson FE, Coburn JC, Siegel KL. Total hip arthroplasty head-neck contact mechanics: a stochastic investigation of key parameters. J Biomech 2014; 47(7): 1634–41.

- http://www.mhra.gov.uk/home/groups/clin/documents/committeedocument/con125995.pdf accessed 24 June 2014.

- http://www2.aaos.org/bulletin/jul96/biomedic.htm accessed on 7 October 2014.

- http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/health/news/11121452/Thousands-of-patients-could-have-unapproved-mix-match-metal-on-metal-hips-say-lawyers.html accessed on 17 April 2015.

- Langton DJ, Jameson SS, Joyce TJ, Gandhi JN, Sidaginamale R, Mereddy P, Lord J, Nargol AV. Accelerating failure rate of the ASR total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2011; 93(8): 1011–6.

- Nassif NA, Nawabi DH, Stoner K, Elpers M, Wright T, Padgett DE. Taper design affects failure of large-head metal-on-metal total hip replacements. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2014; 472(2): 564–71.

- Panagiotidou A, Meswania J, Hua J, Muirhead-Allwood S, Hart A, Blunn G. Enhanced wear and corrosion in modular tapers in total hip replacement is associated with the contact area and surface topography. J Orthop Res 2013; 31(12): 2032–9.

- Sedrakyan A. Metal-on-metal failures--in science, regulation, and policy. Lancet 2012; 379(9822): 1174–6.

- Smith AJ, Dieppe P, Vernon K, Porter M, Blom AW. on behalf of the National Joint Registry of England and Wales. Failure rates of stemmed metal-on-metal hip replacements: analysis of data from the National Joint Registry of England and Wales. Lancet 2012; 379(9822): 1199–204.

- 10th Annual Report of the National Joint Registry for England, Wales and Northern Ireland, Hemel Hampstead, 2013.