Abstract

Background and purpose — Aseptic loosening and infection are 2 of the most common causes of revision of hip implants. Antibiotic prophylaxis reduces not only the rate of revision due to infection but also the rate of revision due to aseptic loosening. This suggests under-diagnosis of infections in patients with presumed aseptic loosening and indicates that current diagnostic tools are suboptimal. In a previous multicenter study on 176 patients undergoing revision of a total hip arthroplasty due to presumed aseptic loosening, optimized diagnostics revealed that 4–13% of the patients had a low-grade infection. These infections were not treated as such, and in the current follow-up study the effect on mid- to long-term implant survival was investigated.

Patients and methods — Patients were sent a 2-part questionnaire. Part A requested information about possible re-revisions of their total hip arthroplasty. Part B consisted of 3 patient-related outcome measure questionnaires (EQ5D, Oxford hip score, and visual analog scale for pain). Additional information was retrieved from the medical records. The group of patients found to have a low-grade infection was compared to those with aseptic loosening.

Results — 173 of 176 patients from the original study were included. In the follow-up time between the revision surgery and the current study (mean 7.5 years), 31 patients had died. No statistically significant difference in the number of re-revisions was found between the infection group (2 out of 21) and the aseptic loosening group (13 out of 152); nor was there any significant difference in the time to re-revision. Quality of life, function, and pain were similar between the groups, but only 99 (57%) of the patients returned part B.

Interpretation — Under-diagnosis of low-grade infection in conjunction with presumed aseptic revision of total hip arthroplasty may not affect implant survival.

Aseptic loosening and infection are 2 common causes of revision in total hip arthroplasty (THA) (Sadoghi et al. Citation2013). Data from the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register and the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register have shown that antibiotic prophylaxis, administered either systemically, locally, or combined, prevents infection and thus reduces revision rates due to infection. Interestingly, it has also been shown that the rates of revision due to aseptic loosening decrease with the use of antibiotic prophylaxis (Malchau et al. Citation2002, Engesaeter et al. Citation2003). As theoretically the use of antibiotics should not have any influence on aseptic loosening, this suggests that the diagnosis of infection was inadequate. Under-diagnosis of infection in THA could possibly reduce the survival of revision hip implants.

One of the major challenges when diagnosing low-grade infection is the accurate identification of microorganisms. These can be difficult to detect with routine diagnostics because of previous antimicrobial exposure or the requirement of certain microorganisms for specific nutrients, and also possibly due to reduced growth rates of biofilm-residing organisms (Fux et al. Citation2003, Schafer et al. Citation2008). To overcome this obstacle, new techniques for detection and identification of bacteria have been introduced. For example, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) on bacterial 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) can theoretically detect as little as 1 bacterium in a sample (Trampuz et al. Citation2003, Clarke et al. Citation2004, Fenollar et al. Citation2006, Kobayashi et al. Citation2009, Bergin et al. Citation2010). The apparent disadvantage of this feature is that PCR detection is susceptible to bacterial contamination (Panousis et al. Citation2005).

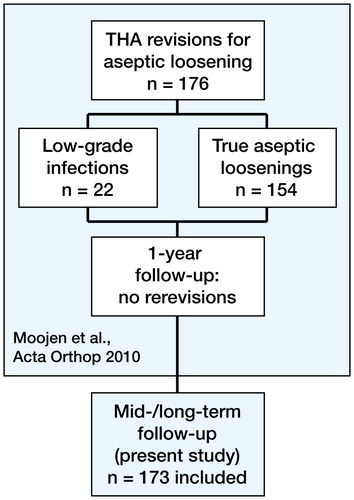

Previously, our group developed and validated a combined 16S rRNA PCR and reverse line blot hybridization (RLBH) technique, which could identify many bacteria at the species level (Moojen et al. Citation2007). This combined technique was then used in a clinical study to test the hypothesis that there is under-diagnosis of infection in patients undergoing a THA revision due to aseptic loosening. In 7 Dutch hospitals, 176 patients undergoing revision of their THA following a preoperative diagnosis of aseptic loosening were included. During surgery, tissue biopsies were obtained for microbiological examination, pathological analysis, and broad-range 16S rRNA PCR with RLBH. We showed that 7 (4%) of these patients had a bacterial infection and an additional 15 (9%) were suspected of having an infection. Of these 22 patients, 2 were given a prolonged period of treatment with antibiotics. After a 1-year follow-up of 170 of the 176 patients, none of the 22 patients with an infection or suspected infection had undergone additional surgery.

In the current study, we performed a mid- to long-term follow-up on this cohort to investigate the effects of missed low-grade infection on implant survival and clinical outcome. The hypothesis was that patients with an undiagnosed low-grade infection would show a higher rate of implant failure and poorer clinical outcome.

Patients and methods

Study design

The initial multicenter prospective cohort study took place between November 2002 and July 2006 (Moojen et al. Citation2010). During this period, 176 patients (127 women) with a preoperative diagnosis of aseptic loosening of their THA were admitted to one of the 7 Dutch hospitals participating in the study (). The diagnosis was based on plain radiographs, ESR, and CRP levels. Furthermore, a large proportion of the patients had an arthrocentesis performed or a radionuclide study. The patients were eligible for inclusion if they were at least 18 years of age and were scheduled for a 1-stage revision of the cup, stem, or both, after a preoperative diagnosis of aseptic loosening. Both first revision cases and re-revision cases were included. Median age at the time of revision surgery was 72 (28–92) years. All patients were scheduled for a 1-stage revision and for a short course (1–5 days) of prophylactic systemic antibiotics. The bacteriological, histopathological, and PCR-RLBH results were analyzed postoperatively. Patients were regarded as infected when the results met the criteria as described by either Spangehl et al. (1998) or Atkins et al. (1999). In addition, the PCR-RLBH results were added to these criteria using the same criteria as for culture according to Atkins et al. (1999) or Spangehl et al. (1998). Since we wanted to analyze low-grade infections specifically, we adjusted the criteria for infection in order to be able to find patients suspected of being infected. A patient was suspected to have an infection when at least 2 culture results or 2 PCR-RLBH results were positive for the same microorganism, or if the pathological analysis showed a definitive positive result for infection. We found that 7 (4%) of these patients had a bacterial infection and an additional 15 (9%) were suspected of having an infection. Of these 22 patients with suspected infection, 2 were treated with a prolonged period of antibiotics after revision surgery, from which 1 received a 2-stage revision. After a 1-year follow-up period in 170 of the 176 patients, none of the 22 patients with a (suspected) infection had received additional surgery (Moojen et al. Citation2010).

Figure 1. Study design. In the previous study, 176 patients with an aseptic loosening of their total hip prosthesis were included. After additional analysis, 22 patients were believed to have a low-grade infection. After a 1-year follow-up, no additional re-revisions were seen in those patients. The present study included 173 patients from the initial study.

With this patient cohort, the present follow-up study was performed to investigate whether an undiagnosed low-grade infection has any influence on the survival of the implant. For this purpose, we compared data between 2 groups: the group of patients with aseptic loosening (AL) and the group of patients with a (suspected) infection (INF). 1 patient was excluded from the current study because that patient received antibiotic treatment during the revision surgery. Between September 2012 and February 2013, data on implant survival and quality of life were collected using a 2-part questionnaire. When needed, additional information was obtained from the medical records.

Data acquisition

All information was handled confidentially, in accordance with the Dutch Personal Data Protection Act. Each patient was appointed a study identification number, according to which all data obtained were registered in a database. If possible in a reasoinable way, patients were asked for their informed consent.

The patients received a 2-part questionnaire. Part A requested information about any possible additional revisions of their THA (e.g. if revised, and if so, the date and reason for revision). In part B of the questionnaire, quality of life was assessed using the EQ-5D, the Oxford hip score (OHS), and visual analog pain scale (VAS pain).

Data analysis

For comparison of the number of additional revisions between the AL and INF groups, Fisher’s exact test was used. Kaplan-Meier analysis was used to create survival curves for the time from revision to re-revision of patients. The Tarone-Ware test was used to compare the survival probability between groups. Some data were non-informatively censored due to the death of patients without undergoing a re-revision. The EQ-5D results were transformed to index values using a standardized descriptive protocol (Group Citation1990, Brooks Citation1996). OHS was assessed using the recommendations for ISIS outcomes (Dawson et al. Citation1996a,Citation1996b, Murray et al. Citation2007). EQ-5D index values and EQ-VAS scores, OHS outcomes, and the VAS pain scores of the groups with infection and without infection were compared using Student’s t-test. A normal distribution of the data was assumed, and Levene’s test revealed that there were no differences between variances. Any p-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 20.0.

Ethics

This study was reviewed and approved by the Medical Research Ethics Committee of the University Medical Center Utrecht (protocol number 12-214/C).

Results

Demographics

Information about additional revisions was available for 173 of the 176 patients (123 of 127 women) who were included in our initial study (152 from the AL group and 21 from the INF group) (Moojen et al. Citation2010). In addition to the patient who was excluded due to antibiotic treatment during the revision surgery, 2 patients declined to participate in the study. Of the patients excluded, 2 were from the AL group and 1 was from the INF group. All other patients gave informed consent. The mean age of the AL group was 77 (SD 12) years and that of the INF group was 77 (SD 9) years. Data on other potential confounding factors were not collected and were not taken into account. The mean duration of follow-up from revision surgery to the follow-up analysis was 7.6 (6.4–9.0) years. During this period, 31 people died (28 in the AL group and 3 in the INF group). Due to small numbers in the group of patients diagnosed with infection (7) and the group of patients suspected of infection (15), both groups were taken together and used as 1 group in the analyses (INF). No significant difference was seen between the number of additional revisions in these groups (p = 0.5, Fisher’s exact test).

Implant survival

Part A of the questionnaire was returned by 137 patients (79%). Of the remaining 36 patients, information about their re-revision (12) and/or death (24) was gathered from the medical records. In the AL and INF groups, 13 patients (9%) and 2 patients (10%) underwent a re-revision of their THA. The 95% confidence interval for the risk difference lay between −0.13 and 0.15. There was no significant difference between the number of additional revisions in these groups (p = 1.0).

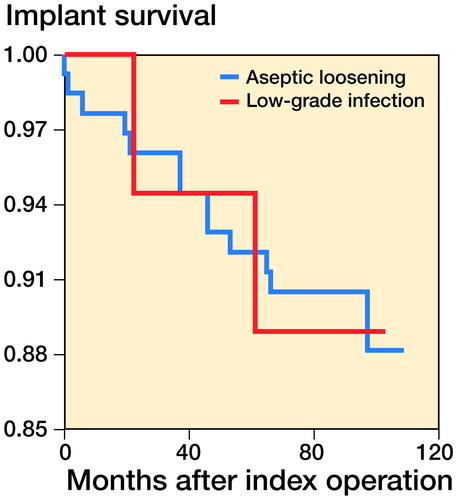

For the implant survival analysis (), 29 patients (26 AL and 3 INF patients, 17%) were missing from the analysis because the date of death was unknown and no information on possible re-revisions was available. None of the missing patients received a re-revision. For the 13 patients in the AL group who had undergone a re-revision by the end of the study, the estimated mean time until revision was 101 (SD 2) months. The 95% confidence interval (CI) of the mean values for survival time ranged between 97 and 106. The estimated mean time to revision for the 2 INF patients was 96 (SD 5) months, with a 95% CI of the mean values for survival time between 87 and 106. There was no significant difference between the survival curves of both groups (p = 0.9).

Quality of life

Part B of the questionnaire was returned by 99 patients (57%). Of these forms, 85 were filled out completely and could be used for the EQ-5D; 94 could be used for both the OHS and VAS pain. 74 patients could not fill out the questionnaire because they were dead (31), lost to follow-up (8), or incapable of filling out the questionnaire for medical reasons (6). In addition, 29 patients declined to fill out the questionnaire.

In both groups, the patients showed a large variation in quality of life, functioning, and pain outcomes. Interestingly, no significant difference was found in health status as measured by the EQ-5D index values of the AL group (0.73 (SD 0.21)) and the INF group (0.73 (SD 0.16)). Furthermore, we found a similar spread in health as measured by the EQ-VAS (69 (SD 20) vs. 69 (SD 17)). No significant difference in score for functioning and hip pain (as measured by the OHS) was observed for the AL patients (34 (SD 11)) and the INF patients (33 (SD 9) (p = 0.7). There was no significant difference in VAS pain between the AL patients (23 (SD 26)) and the INF patients (31 (SD 30)) (p = 0.3).

Discussion

This follow-up study is the first to show that a missed low-grade infection in patients diagnosed with aseptic loosening and receiving a revision THA does not appear to influence the mid- to long-term prognosis. The number of re-revisions and the survival time of the implant were similar between the patients with aseptic loosening and the patients with low-grade infection. Quality of life, hip function, and pain were similar between the groups. These observations are in line with the findings of our previous study after 1 year of follow-up (Moojen et al. Citation2010).

Our study is unique, since until now there have been no studies investigating the influence of underdiagnosed low-grade infections on the number of re-revisions or the survival time of orthopedic implants. To our knowledge, there have been no studies on the mid- to long-term effects of misdiagnosed low-grade infections on other types of implants. There are therefore no studies available for comparison.

A limitation of the present study was the low sample size. Even though 176 patients were included in our initial study, only 2 events in the INF group could be included in the survival analysis. It is possible that we cannot prove any direct consequences of underdiagnosed low-grade infection of a THA, due to low numbers in this group. The risk of type-II error should be kept in mind when interpreting these data. This was also the case when the patients from the infected group and suspected group were combined. Another limitation is that it was only possible to measure cross-sectional quality of life, as quality of life was not assessed in our initial study (Moojen et al. Citation2010). Thus, we cannot draw any conclusions on the effect that under-diagnosis of infection has on quality of life over time. Furthermore, no reliable conclusions can be drawn from the results of the questionnaires due to the large proportion of missing cases and incomplete responses.

Currently, there is no no gold standard available for microbiological diagnosis of infection. Commonly used criteria are those described by Spangehl et al. (Citation1999) and Atkins et al. (Citation1998). By using these criteria, it is possible to detect infections with satisfactory sensitivity and specificity. However, we have shown that in clinical practice low-grade infections are often missed (Moojen et al. Citation2010). One option to prevent under-diagnosis of infection is to lower the stringency of the criteria for the diagnosis, as this would increase sensitivity; however, it would also reduce the specificity. A more desirable option is to use techniques that can diagnose infection more reliably and sensitively in THA than those that are currently used.

A successful treatment of implant-related infection in orthpedics relies on accurate diagnosis and correct identification of microorganisms and their possible resistances to antibiotics. Recently, different approaches for improvement of microbiological diagnosis of infection have been explored. For example, molecular techniques may help to detect and identify the possible presence of bacteria, but molecular biological procedures must be performed with caution because of the risks of interfering contamination (Panousis et al. Citation2005, Fenollar et al. Citation2006, Levy and Fenollar Citation2012). In our previous study (Moojen et al. Citation2010), we used PCR-RLBH in addition to standard diagnostics to test the hypothesis that there is under-diagnosis of infection in patients undergoing a THA revision due to aseptic loosening. That study showed that 4–13% of the 176 included patients with aseptic loosening of their THA probably suffered from an infection. This technique proved to be promising, but it is also associated with difficulties. For example, PCR can only detect the bacterial strains against which the primers are designed. Additionally, the high sensitivity of PCR results in a greater risk of contamination and thereby false positive results. Again, molecular techniques still lack the possibility of testing bacterial resistance. As a result of these limitations, few (if any) clinical laboratories have started to use PCR next to the standard microbiological culture techniques as part of the standard diagnosis.

Another approach for improvement of microbiological diagnosis of infection is the sonication of explanted material (Trampuz et al. Citation2007). With this method, biofilm-residing bacteria are detached from the implant and can then be detected using standard culture methods. A recent meta-analysis on 12 studies showed promising results of using sonication as an additional diagnostic tool to be able to culture biofilm-residing bacteria (Zhai et al. Citation2014). In addition, sonication can be combined with other techniques such as measuring microbial heat production or PCR-hybridization to potentially improve diagnosis of implant-related infection (Esteban et al. Citation2012, Borens et al. Citation2013).

Recently, it was shown that analysis of antimicrobial peptide expression in synovial fluids can provide valuable information for the diagnosis of periprosthetic infection (Gollwitzer et al. Citation2013). Others have also found an increase in interleukins such as IL-1 and IL-6 in synovial fluid in periprosthetic joint infections (Paulsen et al. Citation2002, Deirmengian et al. Citation2005,Citation2010). Moreover, researchers have found 5 biomarkers in synovial fluid that could indicate an infection with high sensitivity and high specificity (Deirmengian et al. Citation2014). These synovial fluid biomarkers may prove to be a valuable tool for the diagnosis of implant-related infections. However, clinical studies should be performed to provide more evidence. Furthermore, the efficacy of diagnosing low-grade infections remains elusive.

The issue of under-diagnosis of low-grade infection will remain a topic of debate until the current detection methods are improved, or until a new method is introduced with high sensitivity and specificity. Even then, the value of improved detection of low-grade infections will have to be established in clinical practice, as the results of the present study suggest that under-diagnosis of infection has no influence on either implant survival or quality of life.

We thank the following people for their contributions: Marianne Koolen, Petra Heesterbeek, Ria Kamies, Vanessa Scholtes, Liesbeth Jutten, Marco Hoozemans, and Jos Elbers.

WB: study design, writing of protocol, inclusion of patients, data analysis, writing of manuscript, and principal investigator. DJFM: study design, writing of manuscript. EV: inclusion of patients, data analysis, and writing of manuscript. AML: study design, writing of protocol, and writing of manuscript. TSW: writing of manuscript. GvH, JG, NJAT, BWS, and BJB: local principal investigators; reviewers of the manuscript. WJAD: review of the manuscript; senior investigator. DG: data analysis, writing of manuscript, and supervision. HChV: study design, writing of manuscript, and supervision.

This study was supported by an institutional research grant from Stryker Orthopaedics (Mahwah, NJ). Stryker had no role in planning of the study, data collection, analysis, interpretation of data, or writing of the manuscript.

- Atkins B L, Athanasou N, Deeks J J, Crook D W, Simpson H, Peto T E, McLardy-Smith P, Berendt A R. Prospective evaluation of criteria for microbiological diagnosis of prosthetic-joint infection at revision arthroplasty. The OSIRIS Collaborative Study Group. J Clin Microbiol 1998; 36 (10): 2932-9.

- Bergin P F, Doppelt J D, Hamilton W G, Mirick G E, Jones A E, Sritulanondha S, Helm J M, Tuan R S. Detection of periprosthetic infections with use of ribosomal RNA-based polymerase chain reaction. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2010; 92 (3): 654-63.

- Borens O, Yusuf E, Steinrucken J, Trampuz A. Accurate and early diagnosis of orthopedic device-related infection by microbial heat production and sonication. J Orthop Res 2013; 31 (11): 1700-3.

- Brooks R. EuroQol: the current state of play. Health Policy 1996; 37 (1): 53-72.

- Clarke M T, Roberts C P, Lee P T, Gray J, Keene G S, Rushton N. Polymerase chain reaction can detect bacterial DNA in aseptically loose total hip arthroplasties. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2004; (427): 132-7.

- Dawson J, Fitzpatrick R, Carr A, Murray D. Questionnaire on the perceptions of patients about total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1996a; 78 (2): 185-90.

- Dawson J, Fitzpatrick R, Murray D, Carr A. Comparison of measures to assess outcomes in total hip replacement surgery. Qual Health Care 1996b; 5 (2): 81-8.

- Deirmengian C, Lonner J H, Booth R E, Jr. The Mark Coventry Award: white blood cell gene expression: a new approach toward the study and diagnosis of infection. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2005; 440: 38-44.

- Deirmengian C, Hallab N, Tarabishy A, Della Valle C, Jacobs J J, Lonner J, Booth R E, Jr. Synovial fluid biomarkers for periprosthetic infection. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2010; 468 (8): 2017-23.

- Deirmengian C, Kardos K, Kilmartin P, Cameron A, Schiller K, Parvizi J. Diagnosing periprosthetic joint infection: has the era of the biomarker arrived? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2014; 472(11): 3254-62.

- Engesaeter L B, Lie S A, Espehaug B, Furnes O, Vollset S E, Havelin L I. Antibiotic prophylaxis in total hip arthroplasty: effects of antibiotic prophylaxis systemically and in bone cement on the revision rate of 22,170 primary hip replacements followed 0-14 years in the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop Scand 2003; 74 (6): 644-51.

- Esteban J, Alonso-Rodriguez N, del-Prado G, Ortiz-Perez A, Molina-Manso D, Cordero-Ampuero J, Sandoval E, Fernandez-Roblas R, Gomez-Barrena E. PCR-hybridization after sonication improves diagnosis of implant-related infection. Acta Orthop 2012; 83 (3): 299-304.

- Fenollar F, Roux V, Stein A, Drancourt M, Raoult D. Analysis of 525 samples to determine the usefulness of PCR amplification and sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene for diagnosis of bone and joint infections. J Clin Microbiol 2006; 44 (3): 1018-28.

- Fux C A, Stoodley P, Hall-Stoodley L, Costerton J W. Bacterial biofilms: a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2003; 1 (4): 667-83.

- Gollwitzer H, Dombrowski Y, Prodinger P M, Peric M, Summer B, Hapfelmeier A, Saldamli B, Pankow F, von Eisenhart-Rothe R, Imhoff A B, Schauber J, Thomas P, Burgkart R, Banke I J. Antimicrobial peptides and proinflammatory cytokines in periprosthetic joint infection. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2013; 95 (7): 644-51.

- Group T E. EuroQol–a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy 1990; 16 (3): 199-208.

- Kobayashi N, Inaba Y, Choe H, Aoki C, Ike H, Ishida T, Iwamoto N, Yukizawa Y, Saito T. Simultaneous intraoperative detection of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus and pan-bacterial infection during revision surgery: use of simple DNA release by ultrasonication and real-time polymerase chain reaction. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2009; 91 (12): 2896-902.

- Levy P Y, Fenollar F. The role of molecular diagnostics in implant-associated bone and joint infection. Clin Microbiol Infect 2012; 18 (12): 1168-75.

- Malchau H, Herberts P, Eisler T, Garellick G, Soderman P. The Swedish Total Hip Replacement Register. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2002; 84-A Suppl 2: 2-20.

- Moojen D J, Spijkers S N, Schot C S, Nijhof M W, Vogely H C, Fleer A, Verbout A J, Castelein R M, Dhert W J, Schouls L M. Identification of orthopaedic infections using broad-range polymerase chain reaction and reverse line blot hybridization. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2007; 89 (6): 1298-305.

- Moojen D J, van Hellemondt G, Vogely H C, Burger B J, Walenkamp G H, Tulp N J, Schreurs B W, de Meulemeester F R, Schot C S, van de Pol I, Fujishiro T, Schouls L M, Bauer T W, Dhert W J. Incidence of low-grade infection in aseptic loosening of total hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthop 2010; 81 (6): 667-73.

- Murray D W, Fitzpatrick R, Rogers K, Pandit H, Beard D J, Carr A J, Dawson J. The use of the Oxford hip and knee scores. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2007; 89 (8): 1010-4.

- Panousis K, Grigoris P, Butcher I, Rana B, Reilly J H, Hamblen D L. Poor predictive value of broad-range PCR for the detection of arthroplasty infection in 92 cases. Acta Orthop 2005; 76 (3): 341-6.

- Paulsen F, Pufe T, Conradi L, Varoga D, Tsokos M, Papendieck J, Petersen W. Antimicrobial peptides are expressed and produced in healthy and inflamed human synovial membranes. J Pathol 2002; 198 (3): 369-77.

- Sadoghi P, Liebensteiner M, Agreiter M, Leithner A, Bohler N, Labek G. Revision surgery after total joint arthroplasty: a complication-based analysis using worldwide arthroplasty registers. J Arthroplasty 2013; 28 (8): 1329-32.

- Schafer P, Fink B, Sandow D, Margull A, Berger I, Frommelt L. Prolonged bacterial culture to identify late periprosthetic joint infection: a promising strategy. Clin Infect Dis 2008; 47 (11): 1403-9.

- Spangehl M J, Masri B A, O’Connell J X, Duncan C P. Prospective analysis of preoperative and intraoperative investigations for the diagnosis of infection at the sites of two hundred and two revision total hip arthroplasties. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1999; 81 (5): 672-83.

- Trampuz A, Osmon D R, Hanssen A D, Steckelberg J M, Patel R. Molecular and antibiofilm approaches to prosthetic joint infection. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2003; (414): 69-88.

- Trampuz A, Piper K E, Jacobson M J, Hanssen A D, Unni K K, Osmon D R, Mandrekar J N, Cockerill F R, Steckelberg J M, Greenleaf J F, Patel R. Sonication of removed hip and knee prostheses for diagnosis of infection. N Engl J Med 2007; 357 (7): 654-63.

- Zhai Z, Li H, Qin A, Liu G, Liu X, Wu C, Li H, Zhu Z, Qu X, Dai K. Meta-analysis of sonication fluid samples from prosthetic components for diagnosis of infection after total joint arthroplasty. J Clin Microbiol 2014; 52 (5): 1730-6.