Abstract

The World Report on Disability makes nine recommendations to ensure the inclusion, participation, and emancipation of people with disabilities. As described by Wylie, McAllister, Marshall, and Davidson (2013), the recommendations present a challenge for the development of services for people with communication disability (PWCD) in the Majority World, particularly recommendation 5: “increasing human resource capacity”, since professionals with training in communication disability are often in extremely short supply. In partial answer to this situation in East Africa, a degree-level education programme for speech-language pathologists (SLPs) commenced in Uganda in 2008. This paper describes the establishment of that degree course, the current context of professional education, service development, and delivery, and describes how the World Report on Disability recommendation of increasing human resource capacity could be further addressed using culturally-appropriate, accessible, and innovative models of education. It highlights the need for a multi-strand and long-term approach to addressing communication disability at impairment, activity, and participation levels and offers a vision for the future of services in Uganda.

Introduction

Uganda has a population of 34.5 million people (CitationUnited Nations Development Programme (UNDP), 2012), 88% of whom live rurally and 24.5% of whom are estimated to live in chronic poverty1 (CitationMinistry of Gender, Labour and Social Development, MGLSD, 2011). It is 161st on the Human Development Index (UNDP, 2012) and, with the highest birth-rate in the world2 (CitationWorld Bank, 2012), the rapidly expanding population puts enormous pressure on public services. Despite Uganda having some of the most progressive social legislation in the region (CitationInternational Labour Organization (ILO)/Irish Aid, 2009), the economy relies heavily upon international donor support to sustain its social services. Human resource capacity to deliver such services is extremely limited (CitationNatukunda, 2012) and access remains a challenge for many; for example, 51% of people do not have access to any form of public healthcare (CitationKelly, 2009).

Despite having ratified the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disability (UNCRPD) in 2008, 5 million disabled people (16% of the population) in Uganda have difficulty accessing the services they need to live independent, productive lives (CitationILO/Irish Aid, 2009; CitationMGLSD, 2011). As a result, ˜90% of children with a disability are limited in their ability to attend school, an estimated 29.2% of children with communication disability are unable to attend school at all, and 50.1% of adults with communication disability do not work (CitationMGLSD, 2011). Against this backdrop an education program for professionals to meet the needs of people with communication disability (PWCD) in Uganda was established (CitationRobinson, Afako, Wickenden, & Hartley, 2003; CitationWylie, McAllister, Davidson, & Marshall, 2013).

Planning the development of a professional training course

Speech-language pathology3 services have been available in Uganda since 1986, when Voluntary Services Overseas (VSO), a UK non-governmental organization, began to send volunteer speech-language pathologists (SLPs) to Uganda (CitationAfako, 2012). However, it was acknowledged that a centrally-located, expatriate, short-term SLP could not provide sustainable input for the increasing number of PWCD seeking services. Over a number of years, discussions with key stakeholders in disability services were held, culminating in a workshop in 2002, which brought together representatives from government, universities, non-governmental organizations, community-based organizations, hospitals, schools, service users, and community-based rehabilitation program, to plan the provision of appropriate, culturally sensitive, and accessible services for PWCD (CitationRobinson et al., 2003). Government commitment was demonstrated by the workshop being part-funded by the Government of Uganda and by delegates committing to employ professionals in public services upon their graduation (CitationRobinson et al., 2003).

Paving the way forward

In line with views that Minority World models should not be transposed to Majority World countries (CitationHartley, 1998; CitationHartley & Wirz, 2002; CitationInternational Association of Logopedics and Phoniatrics, 1998; CitationPickering, 2003; CitationWylie et al., 2013), delegates agreed to establish a bespoke course to educate professionals to lead service provision for PWCD in Uganda. A degree program was proposed to ensure that the first groups of SLPs would be equipped with the skills to advocate for PWCD by generating an evidence base and advocating for effective policy in a context where communication disability is little understood, highly stigmatized, and low on donor and political priority lists (CitationHartley, 1998). The curriculum was designed, based upon suggestions from the speech-language pathology course in Sri Lanka (Wickenden, Hartley, Kariyakarnawa, & Kodikara, 2003), that professionals in the Majority World are often faced with very different working environments and constraints from those in the Minority World, for example limited access to therapy materials and lack of supervision from experienced clinicians. Indeed, CitationWickenden et al. (2003) highlighted the need for a completely different skill set and stressed the importance of equipping students with creativity, flexibility, and skills of self-reflection and evaluation, given the lack of supervision upon graduation.

The current situation

Twelve SLPs have graduated from the speech-language pathology course, five are awaiting graduation and nine students are in training. Students pay fees to attend the course. So far, the Tanzanian and Rwandan governments have funded students to complete the course, but this is not yet the case for Ugandan students, despite the original political commitment to the profession. Teaching and program management are currently provided by international volunteers and local teaching staff from Makerere University.

Ensuring program sustainability is vital for a new, small, and unknown profession which has received substantial international personnel support. To this end a revised curriculum has ensured partnerships have been developed between the College of Health Sciences and the Departments of Psychology and Linguistics, at Makerere University. Funding has also been sought from Makerere University to employ lecturers from other specialist institutions which train special education professionals and community-based rehabilitation workers and local community-based organizations. A transition plan has also been developed to reduce reliance on international volunteer lecturers (Makerere University Speech and Language Therapy Unit, CitationSLTU, 2011). In order to ensure graduates receive professional support and postgraduate development opportunities, a mentoring and support program is being implemented in collaboration with Manchester Metropolitan University, UK,4 to provide graduates with an experienced speech-language pathology mentor and to provide a range of professional training.

It will take many years to train sufficient numbers of SLPs to meet the needs of all PWCD in Uganda, and this may not be the most appropriate way to meet the needs of all Ugandan PWCD. Although community-based services have been recommended by a number of prominent researchers as the most efficient and cost-effective method of service delivery (CitationAltanzul, Erdenbayar, Ng, Byambasuren, Sharma, & Tsetsegdary, 2009; CitationHartley, 1998; CitationHartley & Wirz, 2002), they may not be able to address all aspects of impairments, activity limitations, participation restrictions, personal, and contextual issues (CitationWorld Health Organization, 2001). Community-based rehabilitation workers may be best placed to tackle matters of activity limitation and participation restriction in their communities, to address issue of stigma and exclusion, and to promote access to public services and inclusion in community activities (CitationWirz & Lichtig, 1998). They may, however, be potentially less able to offer support and rehabilitation at the impairment level, without significant additional professional training.

To offer limited services will impede the emergence of a more holistic approach to supporting PWCD. For this reason, it has been imperative to ensure that students training to become SLPs in Uganda do not become professionals who practise purely within a restricted medical model to treat impairments, but become practitioners who see disability as “complex, dynamic and multidimensional” (CitationWorld Health Organization and The World Bank, 2011, p.3). It is also crucial to ensure that students gain skills in transferring their knowledge to others, such as community-based rehabilitation workers, teachers, nurses, doctors, and family members (CitationWickenden et al., 2003).

The future

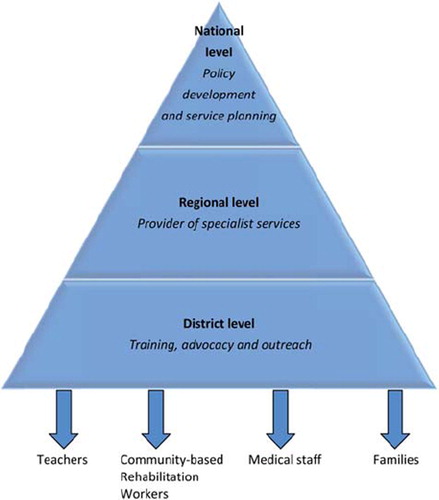

In 2010, a further workshop was held with key stakeholders to revisit the commitments made in 2002 and to plan a structure for services for PWCD in the health and education sectors. Delegates agreed that SLPs in the health sector should be employed at national, regional, and district levels, providing varying levels of expertise (see ). This was later recommended for action by the Ugandan Permanent Secretary for Health in 2011.5 In the education sector delegates suggested that SLPs should be posted at national, district, and community levels, with community SLPs having much more of an advocacy and training role to ensure maximum coverage (CitationMakerere University SLTU, 2010).

It was outside the scope of the workshop to discuss plans beyond a 10-year time frame. A multi-strand approach to tackling communication disability in Uganda can, however, be envisaged, which includes graduate SLPs becoming sufficiently skilled to provide specialist holistic services and to offer training to other professionals. It is also imperative that a credible professional group is established in order to advocate for the provision of services for PWCD within national policy and planning processes. For this reason, amongst others, the Association of Speech and Language Therapists in East Africa (ASALTEA) is being established, with a vision to “ensure delivery of high quality Speech and Language Therapy services through innovative partnership with training institutions, governments and communities in East Africa and beyond” (CitationASALTEA, 2011). The organization recognizes its role in advocating for services with a credible, coherent, and professional voice and, using documents such as the World Report on Disability (CitationWorld Health Organization and the World Bank, 2011), UNCRPD and Ugandan legislation, to become agents of change.

Challenges ahead

Although the speech-language pathology degree program is producing specialist staff as recommended in World Report on Disability, service provision for PWCD is still in its infancy in Uganda. A major challenge lies in the fact that a large proportion6 of Ministry of Health (MoH) funding comes from international donors (CitationMoH, 2010) who themselves do not necessarily recognize, understand, or prioritize PWCD and have their own, pre-determined health agendas. This may be understandable in a context where life-threatening infectious disease is rife, although not excusable in light of international legislation on disability (e.g., UNCRPD) and its documented link to chronic poverty (CitationYeo, 2001).

Unfortunately, communication disability is rarely specifically mentioned within wider disability discourse and is often conflated with sensory disability (CitationWylie et al., 2013). The challenge for speech-language pathology graduates, therefore, is not only to provide services where they can, but to become the voice of PWCD and their advocates for change, using research-based evidence (CitationJones, Marshall, Lawthom, & Read, 2013), international law, and policy commitments to support their arguments.

Conclusion

As highlighted by CitationWylie et al. (2013), communication disability remains under-acknowledged and under-prioritized across the globe. In Uganda, a small number of SLPs are beginning to raise awareness of the social, economic, health, and educational implications of communication disability, on individuals, families, and communities.

A group of specialists may be insufficient to provide speech-language pathology to all Ugandans in need. However, the establishment of a specialist profession is critical for facilitating policy and service development, research, and training other professionals working with PWCD. These are crucial if communication disabilities are to be recognized, understood, and services funded. Moreover, it is critical that local professionals are able to offer sustainable, culturally appropriate, nuanced, and accessible services for PWCD, and this can only be achieved when local professionals are empowered to develop services in their own communities. It is possible that, once a credible cadre of experienced professionals is available and teaching capacity exists, a course aimed at skilling up other professionals can be developed, as has occurred in South Africa (CitationAron, Bauman, & Whiting, 1967; CitationBortz, Jardine, & Tshule, 1996). Of course it is imperative that international experts continue to support the new speech-language pathology course and graduates as they acquire experience and further training to allow them to independently manage and develop the degree program. The experience in Sri Lanka suggests that this can take up to 10 years (CitationWylie, McAllister, Marshall, Wickenden, & Davidson, 2012).

It is clear that a “one size fits all” model of training and service development to increase human resource capacity cannot be applied across different cultural, geographical, and economic contexts, and that novel models of education and service delivery are required (CitationWylie et al., 2013). In Uganda it is possible that a multi-strand, long-term approach to the development of education and services may be the most appropriate to address communication disability at impairment, activity limitation, and participation restriction levels. However, this cannot happen in isolation and, until Uganda is able to tackle issues of social exclusion of people with disabilities as a whole, communication disability may remain low on the political agenda.

Local SLPs therefore have a critical role to play in advocating for PWCD who cannot necessarily speak for themselves but, as CitationWylie et al. (2013) note, paradoxically need their voices to be heard. This can be done in part through research (CitationJones et al., 2013) and the establishment of service-user groups. The World Report on Disability (CitationWorld Health Organization & The World Bank, 2011) and other key international guidelines can also be used as tools to raise the profile of communication disability in the Majority World and advocate for the provision of services for PWCD. In Uganda, increasing human resource capacity would then ensure that the other World Report on Disability recommendations can be addressed more fully and with greater success.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank students and graduates of the speech-language pathology degree program; Staff of the College of Health Sciences, Makerere University; The ENT Department, Mulago Hospital; All volunteer SLPs, particularly Sarah Raheja, Isla Jones, and Marise Fernandes; Staff of VSO International, particularly former programme manager Dr Sarah Kyobe; The Ugandan Ministries of Health, Education, Public Service and Gender, Labour and Social Development; and all who have contributed to the establishment of the speech- language pathology profession in Uganda.

Notes

Defined as people living on an income of $1.25 per day or less (CitationWorld Bank, 2005).

6.3% in 2010/2011.

Although the term “speech-language pathology” is used throughout the text, the term used in Uganda is “speech and language therapy”.

Funded by the Nuffield Foundation, UK.

This issue is now being pursued further by the Ugandan Ministry of Health.

23.8% on budget funding and 40% off budget funding (CitationWorld Health Organization, 2008).

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Afako, R. (2012). Keynote address. Paper presented at the 4th East African Conference on Communication Disability, Kampala, Uganda.

- Altanzul, N., Erdenbayar, L., Ng, C., Byambasuren, S., Sharma, N., & Tsetsegdary, G. (2009). Community mental health care in Mongolia: Adapting best practice to local culture. Australasian Psychiatry, 17, 375–379.

- Aron, M., Bauman, S., & Whiting, D. (1967). Speech therapy in the Republic of South Africa: Its development, training and the organisation of services. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 2, 78–83.

- Association of Speech and Language Therapists in East Africa (ASALTEA). (2011). Minutes of the first ASALTEA steering committee meeting (3/8/11). Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda.

- Bortz, M., Jardine, C., & Tshule, M. (1996). Training to meet the needs of the communicatively impaired population of South Africa: A project of the University of Witwatersrand. European Journal of Disorders of Communication, 3, 465–476.

- Hartley, S. (1998). Service development to meet the needs of ‘people with communication disabilities’ in developing countries. Disability and Rehabilitation, 20, 277–284.

- Hartley, S., & Wirz, S. (2002). Development of a ‘communication disability model’ and its implication on service delivery in low-income countries. Social Science and Medicine, 54, 1543–1557.

- International Association of Logopedics and Phoniatrics. (1998). Guidelines for initial education in logopedics. Folia Phoniatrica et Logopedica, 50, 230–234.

- International Labour Organisation (ILO)/Irish Aid. (2009). Decent work for people with disabilities: Inclusion of people with disabilities in Uganda. Available online at: http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/@ed_emp/@ifp_skills/documents/publication/wcms_115099.pdf, accessed 20 January 2012.

- Jones, I., Marshall, J., Lawthom, R., & Read, J. (2013). Involving people with communication disability in research in Uganda: A response to the World Report on Disability. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 15, 76–79.

- Kelly, A. (2009). Healthcare a major challenge for Uganda. The Guardian Online. Available online at: http://www.guardian.co.uk/katine/2009/apr/01/healthcare-in-uganda, accessed 5 June 2012.

- Makerere University SLTU. (2010). Embedding speech and language therapy services in Uganda's health and education systems. Available online at: http://mak.academia.edu/helenbarrett/Papers/713940/Embedding_Speech_and_Language_Therapy_in_Ugandas_Health_and_Education_System>, accessed 25 May 2012.

- Makerere University SLTU. (2011). Makerere University Speech and Language Therapy Unit: Strategic plan 2011–2016. Unpublished.

- Ministry of Gender, Labour and Social Development (MGLSD). (2011). The social development sector statistical abstract 2009/2010. Kampala: Government of Uganda.

- Ministry of Health (MoH). (2010). Health sector strategic investment plan 2010/2011 – 2015/2015. Promoting people's health to enhance socio-economic development. Kampala: Government of Uganda.

- Natukunda, A. (2012). Uganda: Nursing Mulago's staff shortages. The Independent. Available online at: http://allafrica.com/stories/201202270856.html, accessed 5 June 2012.

- Pickering, M. (2003). Shared territories: An element of culturally sensitive practice. Folia Phoniatrica et Logopedica, 55, 287–292.

- Robinson, H., Afako, R., Wickenden, M., & Hartley, S. (2003). Preliminary planning for training speech and language therapists in Uganda. Folia Phoniatrica et Logopedica, 55, 322–328.

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). (2012). International human development indicators: Uganda country profile. Available online at: http://hdrstats.undp.org/en/countries/profiles/UGA.html, accessed 28 May 2012.

- Wickenden, M., Hartley, S., Kariyakaranawa, S., & Kodikara, S. (2003). Teaching speech and language therapists in Sri Lanka: Issues in curriculum, culture and language. Folia Phoniatrica et Logopedica, 55, 314–321.

- Wirz, S., & Lichtig, I. (1998). The use of non-specialist personnel in providing a service for children disabled by hearing impairment. Disability and Rehabilitation, 20, 189–194.

- World Bank. (2005). New data show 1.4 billion live on less than US$1.25 a day, but progress against poverty remains strong. Available online at: http://www.worldbank.org/en/news/2008/09/16/new-data-show-14-billion-live-less-us125-day-progress-against-poverty-remains-strong, accessed 5 June 2012.

- World Bank. (2012). Uganda: Country Brief. Available online at: http://web.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/COUNTRIES/AFRICAEXT/UGANDAEXTN/0,,menuPK:374947˜pagePK:141132˜piPK:141107˜theSitePK:374864,00.html, accessed 29 May 2012.

- World Health Organization. (2001). ICF: International classification of functioning, disability and health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization. (2008). Tanzania national health accounts 2002 / 2003 and 2005 / 2006. Geneva: World Health Organization. Available online at: http://www.who.int/nha/docs/en/Tanzania_NHA_report_english.pdf, accessed 5 June 2012.

- World Health Organization and The World Bank. (2011). World report on disability. Geneva: World Health Organization. Available online at: http://www.who.int accessed 18 January 2012.

- Wylie, K., McAllister, L., Davidson, B., & Marshall, J. (2013). Changing practice: Implications of the World Report on Disability for responding to communication disability in underserved populations. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 15, 1–14.

- Wylie, K., McAllister, L., Marshall, J., Wickenden, M., & Davidson, B. (2012). Overview of issues and needs for new speech-language pathology university programs in developing countries. Paper presented at the 4th East African Conference on Communication Disability, Kampala, Uganda.

- Yeo, R. (2001). Background paper 4: Chronic poverty and disability. Somerset: Action on Disability and Development.