Abstract

Testicular volume, hormones, and growth factors are used as predictors of finding motile testicular sperm in azoospermic men. In this study, the possible predictive value of very simple parameters such as systematic history, clinical examination, and determination of ejaculate volume have been evaluated. Two-hundred and sixty-two consecutive non-vasectomized men with azoospermia/aspermia were evaluated by systematic history, clinical examination, ultrasonography of the scrotal content, and hormonal and genetic analyses. Hormonal analyses included, as a minimum, determination of follicular stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinizing hormone (LH), and testosterone, while genetic analyses included karyotyping and examination for cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) mutations and Y microdeletions.

In seventy-six cases (29%) genetics was the most likely cause of azoospermia. For men with at least one CFTR mutation, motile sperm could be detected in 100% of 13 men with congenital bilateral absence of vasa deferentia (VD) but only in 44% of 18 with present VD. Ejaculate volumes were significantly lower (2.3 mL versus 3.6 mL) in 81 men with motile testicular sperm detected compared to 111 men without detectable motile sperm (p < 0.001; Student's t-test), and the difference was still significant after exclusion of men carrying a CFTR mutation. Based on the present data, an ejaculate volume of 2.5 mL was considered a useful threshold value. Furthermore, an inhomogeneous histological pattern with maturation of sperm in small islands isolated in tissue showing Sertoli cell only (SCO) pattern seems characteristic for men with a history of cryptorchidism (negative predictive value: 95%).

In addition to FSH, testicular volume, and other endocrine factors, it is important to consider that very simple factors such as ejaculate volume and presence or absence of VD in men with CFTR mutations might be used as predictors according to the chance of finding motile testicular sperm. Evidence for a strong association between a history of cryptorchidism and an inhomogeneous histological pattern with maturation of sperm in islands in tissue presenting SCO pattern might indicate that multiple TESEs should be considered in men with a history of cryptorchidism.

Introduction

Achieving his own biological child is only possible for an azoospermic man as long as he produces sperm or sperm precursors in the testes. In Denmark one is not allowed to use sperm precursors for fertilization of oocytes. The role of many hormones and growth factors including follicular stimulating hormone (FSH) [de Kretser et al. Citation1974], inhibin-B [Goulis et al. Citation2009], and anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) [Goulis et al. Citation2009] have been evaluated – either isolated or in combination - to predict the chance of being able to obtain useful testicular sperm from azoospermic men. To date, no test, or combination of tests, seem sufficient to predict whether testicular sperm can be retrieved from azoospermic men.

Despite the fact that the major part of the ejaculate comes from the seminal vesicles and prostate [Gonzales Citation1989], we have long had the impression that low ejaculate volume seems associated with an increased chance for obtaining testicular sperm. We found it important to examine whether this can be documented, and whether it is possible to determine a useful threshold value.

In testicular biopsies from azoospermic men with a history of cryptorchidism we have often observed an inhomogeneous histological pattern with maturation to fully mature sperm in islands in tissue showing only Sertoli cells. Therefore, we have found it important to determine whether this histological pattern is more often observed in azoospermic men with a history of cryptorchidism than in other azoospermic men. In addition we wanted to evaluate whether testicular sperm from men with a history of cryptorchidism establish pregnancy equally efficient as do other testicular sperm. If the results are to be useful in clinical practice, it is important to look at an unselected population of men referred to fertility clinics without preceding selection.

To resolve these important issues we have performed an historical prospective study with the primary aims of evaluating whether ejaculate volume predicts the chance for obtaining testicular sperm and if the testicular histological pattern in patients with a history of cryptorchidism predicts the chance for obtaining testicular sperm. Our secondary aims were to evaluate whether the presence or absence of vasa deferentia (VA) in azoospermic men carrying a cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) mutation predicts the chance for obtaining testicular sperm and if sperm from azoospermic men with a history of cryptorchidism are just as fertile as testicular sperm from other azoospermic men.

Results

As shown in , the distibution of men with chromosomal abnormalities, e.g., 47,XXY karyotype [Mau-Holzmann Citation2005], CFTR mutations [von Eckardstein et al. Citation2000; Lissens et al. Citation1996], and Y deletions [Simoni et al. Citation2007] is very similar to previously published data [Fedder et al. Citation2004], suggesting that the population examined in this study was representative of other populations. As no Y microdeletion were detected in the two men of 46,XX karyotype, these men may harbor Y chromosome material.

Table 1. Genetic etiologies detected among 262 men examined due to azoospermia/aspermia.

Ejaculate volume

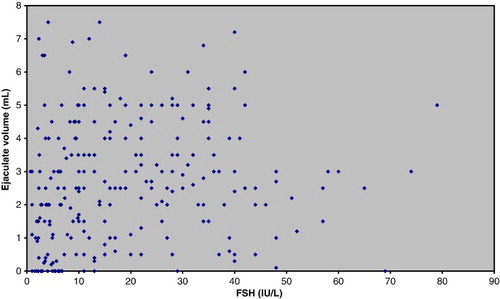

Of 203 men undergoing TESE (Tru-Cut biopsies), motile sperm were observed in 95 men (47%) and immotile sperm in an additional 21 men (10%). As expected, lower FSH levels (11.3 IU/L versus 21.2 IU/L) and larger testicular volumes (25.0 mL versus 14.1 mL) were found in the group of men in whom motile sperm were observed. In addition, significantly lower ejaculate volumes (2.3 mL versus 3.6 mL) were detected in the group with motile sperm, even after exclusion of the men carrying CFTR mutations (2.8 mL versus 3.4 mL) (). Significant associations between low ejaculate volume and low FSH level () or low ejaculate volume and high testicular volume (data not shown) could not be demonstrated.

Figure 1. Association between ejaculate volumes and FSH values for 262 azoospermic, non-vasectomized men.

Table 2. Mean ± SD (ranges), t- and p-values of concentrations of FSH and testicular and ejaculate volumes according to the possibilities of detecting motile testicular sperm useful for treatment.

Ejaculate volumes were generally lower for the 33 (33 out of 34 were able to ejaculate) men carrying at least one CFTR mutation (1.9 mL ± 1.7 mL; range: 0.2 mL-7.5 mL) compared to 214 azoospermic men without a CFTR mutation (3.0 mL ± 1.7 mL; range: 0.1 mL-7.5 mL) (p < 0.01, Student's t-test. For further details see ). Fourteen men unable to ejaculate were not included in this calculation. Furthermore, for the 13 CFTR-men having congenital bilateral absence of vasa deferentia (CBAVD), the ejaculate volumes were even lower (0.9 mL ± 0.6 mL; range: 0.3 mL-2.0 mL) than for the 18 CFTR-men with apparently normal presence of VD (2.7 mL ± 1.9 mL; range: 0.2 mL-7.5 mL) (p < 0.01, Student's t-test). The 13 men with CBAVD showed low FSH values, and in all these cases it was possible to find motile sperm for TESA treatment. In testes of the men with CFTR mutation and VD, it was only possible to find sperm in 44% (8 of 18) of the cases. The men from whom sperm were found, most often showed low ejaculate volumes and low FSH values. In the case of the two men with a ΔF508 mutation and VD presence, ejaculate volumes were 0.2 mL and 0.5 mL and FSH 4.7 IE/L and 4.0 IE/L. In the case of the two men with congenital unilateral absence of vasa deferentia (CUAVD) and incomplete VD, the ejaculate volumes were in between.

Table 3. Ejaculate volumes, FSH values, testis volumes, and the chance of retrieving motile sperm from testicular biopsy arranged according to respective CFTR mutations and presence or absence of vasa deferentia.

As ejaculate volumes were associated with the chance of finding sperm useful for fertility treatment (), defining a threshold value for clinical practice was sought. Therefore, the material was divided according to whether it was possible to find motile sperm, only immotile sperm, or no sperm in testicular biopsies, and data on men and ejaculate volume were considered in 0.5 mL intervals (). On the basis of these data we consider 2.5 mL as a useful threshold value. Considering ejaculate volume < 2.5 mL as a predictor for the presence of motile testicular sperm, the sensitivities were 57% and 44%, respectively, and the respective specificities were 75% and 74% after inclusion and exclusion of men carrying CFTR mutations. Positive predictive values of 63% (CFTR mutations included) and 50% (CFTR mutations excluded) and negative predictive values of 70% (CFTR mutations included) and 69% (CFTR mutations excluded) were found.

Table 4. Percentage distribution of 192 patients with detectable motile sperm, only immotile sperm, or no sperm at all in testicular biopsies, arranged according to ejaculate volumes.

History of cryptorchidism

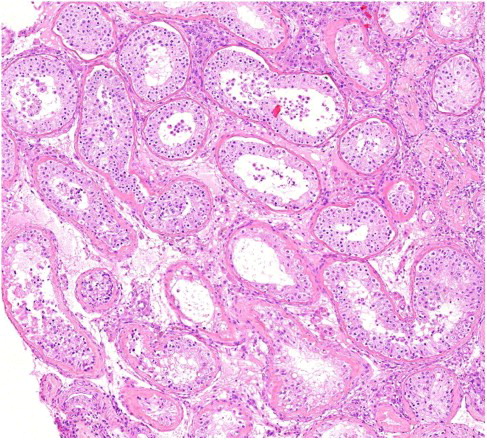

As stated in , an inhomogeneous pattern with spermatogenesis and maturation of sperm in isolated islands in an ocean of seminiferous tubules with only Sertoli cells was particularly characteristic for men with a history of cryptorchidism (p < 0.0001, ). Of these 59 men, the condition had been bilateral in 42, unilateral in 15, and non-recognizable in two cases. In five cases the men had only one testis and in seven other cases one testis was hidden in the inguinal canal or abdomen and therefore not available for immediate biopsy. In either case ultrasonography did not suggest carcinoma in situ or malignancy. Not surprisingly, similar histology was obtained from both the left and the right testis of men with bilateral cryptorchidism. In addition, 11 of the 15 men with unilateral cryptorchidism, in whom bilateral biopsies were taken, very similar testicular sizes and histological patterns were obtained from each testis. Out of at least 26 cases with a history of bilateral cryptorchidism, 22 had a bilateral and 4 a unilateral orchiopexia, while 10 out of 15 cases with a history of unilateral cryptorchidism had an orchiopexia. It was not possible to retrospectively detect any significant association between orchiopexia or age at treatment and histology.

Figure 2. Histological micrograph showing variation of spermatogenesis in different seminiferous tubules of the human testis from an azoospermic man (Photo: Bjarne Nielsen, Patological-anatomical Department, Vejle Hospital, Denmark).

Table 5. Testicular histological patterns arranged according to a positive or negative history of previous cryptorchidism.

For the cryptorchid patients, occurrence of islands with spermatogenesis could not be associated to orchiopexia. Reliable information about the precise localization of the testes in childhood was not possible to obtain, and it was not possible to distinguish between true undescended and ectopic testes [Fedder and Boesen Citation1998].

Occasionally the pathologists identified Leydig cell hyperplasia or peritubular fibrosis in the testicular tissue from the men with a history of cryptorchidism. However, except for one case with hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism, testosterone levels were within or slightly above the normal range and LH levels were in every case within the normal range, suggesting a normal Leydig cell function.

When examining the predictive value of a history of cryptorchidism for the chance to obtain motile sperm, the fertility potential of motile sperm used for ICSI was apparent, although it has not been the main aim of this study. Nineteen of 81 couples with motile sperm were, after andrological examination in our center, treated in a local fertility center. To date 96 stimulated microinsemination treatment cycles with multiple testicular biopsies in 50 couples were completed in our fertility clinic. In a further 7 couples where the female partner was stimulated for oocyte aspiration, it was not possible to again identify testicular sperm; of those, 4 had a history of cryptorchidism (). The remaining 5 azoospermic men with motile testicular sperm either had no female partner, a female partner with too high a body mass index (BMI > 30), or were just not ready for treatment for other reasons.

Table 6. Fertilization, cleavage, implantation, and pregnancy rates in relation to history of cryptorchidism in 50 couples undergoing 96 stimulated microinsemination treatment cycles with multiple testicular biopsies.

Except for a nearly identical fertilization rate for the men with and the men without a history of cryptorchidism, history of cryptorchidism seemed to give slightly reduced successes in again identifying motile testicular sperm, cleavage, implantation, clinical pregnancy, and live birth rates (). Patients treated with epididymal (usually vasectomised men) or frozen-thawed sperm were not included in this analysis.

As maturation of sperm in islands might call for multiple biopsies compared to a uniform histology, it is important to analyze the predictive value of a previous history of cryptorchidism while considering the chance of showing the inhomogeneous histological pattern of spermatogenesis in islands. Associating cryptorchidism and histological patterns of spermatogenesis in islands, a sensitivity of 81% and a specificity of 83% were observed, while the positive and negative predictive values were 53% and 95%, respectively (). Among the 31 men with a history of previous cryptorchidism and spermatogenesis with mature sperm in islands, motile sperm were obtained in 15 (48%).

Discussion

The level of genetic diagnoses in this study population is in accordance with other studies reflecting that the population is unselected (). A frequency of 11.1% abnormal karyotypes is consistent with the 13.1% found by Mau-Holzman [2005], and a frequency of Y deletions of 5.3% is compatible with an estimated frequency of around 8% in men with non-obstructive azoospermia [Simoni et al. Citation2007].

Ejaculate volume

The predictive value of testicular volume and FSH for the chances of finding motile sperm useful for treatment is well documented [de Kretser et al. Citation1974], and the use of these parameters is widespread. In addition, several papers have focused on the possible additive predictive value of inhibin B and AMH [Goulis et al. Citation2009]. In this report we focus on the predictive value of simple historic information and semen volume for the chances of finding motile sperm in testicular biopsies from azoospermic men. A significantly lower mean ejaculate volume was found for the group of men with motile sperm compared to those without motile sperm. Low ejaculate volumes did not show any clear correlation to FSH levels ().

Significantly smaller ejaculate volumes were observed in the 34 men shown to carry a CFTR mutation. This may reflect that the seminal vesicles are missing or hypoplastic, rather than obstruction of the VD. As only a few of the men carrying CFTR mutations had rectal sonography performed, it was not possible to associate seminal volumes and specific CFTR mutations to the size of the seminal vesicles. However, even after exclusion of the men carrying CFTR mutations, the mean ejaculate volume was significantly lower for men with detectable motile sperm ().

This study indicates that CBAVD and low ejaculate volumes increase the chance of finding motile testicular sperm, as motile sperm were found in all 13 CFTR carriers with CBAVD. The IVS8-5T mutation, located to the intron of the CFTR gene, may have a less intensive negative influence on the male genital tract, as only one of 8 men carrying only this mutation showed CBAVD. Motile sperm were found in only 4 of the 7 men with apparent normal VD, suggesting another etiology being the cause of the azoospermia. As discussed below this well illustrates some of the difficulties in dividing azoospermia into obstructive and non-obstructive.

Aiming to define an ejaculate volume threshold value useful in clinical practice, patients were arranged after size of the ejaculate volumes (). In our opinion, the present data support 2.5 mL as a useful threshold value when ejaculate volume is used as a predictive parameter for the chance to obtain testicular sperm.

History of cryptorchidism

For most men the nearly 2 cm long and relatively large testicular biopsies should be representative for the histological picture throughout the whole testis. This is supported by a clear impression of only a negligible difference between biopsies taken from the same patient at the same occasion.

An association between cryptorchidism and decreased sperm concentration is well documented in the literature [Wohlfahrt-Veje et al. Citation2009]. The results presented in this study show that a histological pattern with small islands of normal testicular tissue in tissue showing SCO syndrome is particularly characteristic for men with a history of cryptorchidism. Even for the men with a history of cryptorchidism and SCO syndrome, presence of small islands with normal spermatogenesis, not caught by the biopsy needle, cannot be excluded. For azoospermic men with a history of cryptorchidism it may be particularly relevant to consider multiple TESEs [Seo and Ko Citation2001] and microsurgery [Tsujimura Citation2007] to obtain sperm from the often isolated islands with normal testis tissue. Although a positive predictive value of finding an inhomogeneous pattern with maturation of sperm in islands of only 51% were found, a negative predictive value of 95% shows that the chance of finding an inhomogeneous histological pattern in an azoospermic man is very low unless the man has a history of cryptorchidism. This suggests that if the man has no history of cryptorchidism, one testicular biopsy most probably is representative, and the man could be spared multiple TESEs.

In this study it was not possible to demonstrate any significant associations between a history of cryptorchidism and the ability at a later date (months) to again identify testicular sperm (following diagnostic TESE) and fertilization rate, cleavage rate, implantation rate, clinical pregnancy rate, or live birth rate. This is in accordance with other studies [Haimov-Kochman et al. Citation2010; Vernaeve et al. Citation2004; Negri et al. Citation2003]. Unless using a cohort of cryptorchid boys well-defined through childhood [Fedder and Boesen Citation1998], at present, it is very difficult to get exact information about the previous positions of the testicles and details about previous therapy, including date for treatment [Raman and Schlegel Citation2003]. Such information would help in defining subgroups of men with a history of cryptorchidism, who should be treated differently from the main group of azoospermic men.

Defining one single parameter which can predict whether a man (with at least one testis) produces sperm at this point seems impossible. FSH concentration and testicular volume are well known useful parameters. This study shows that in addition, low semen volumes increase the chance of finding motile testicular sperm. Low ejaculate volumes in combination with CBAVD is suggestive of a CFTR carrier mutation, and that the chances of finding motile testicular sperm are good.

The study also pinpoints the importance of paying particular attention to men with a history of cryptorchidism in attempting to retrieve motile sperm from testicular biopsy as normal sperm production is often found in small islands located in testicular tissue showing Sertoli cell only syndrome. Therefore, multiple TESEs may be considered for these men, while men without a history of cryptorchidism could be spared such intrusive treatment.

Azoospermia is often divided into obstructive (OA) and non-obstructive azoospermia (NOA). This is done on the basis of testicular histology, history, clinical examination (e.g., lack of the scrotal parts of the vasa deferentia), and laboratory analyses (e.g., presence of round germ cells in semen) [Fedder et al. Citation2004]. However, it might be difficult to distinguish between OA and NOA, and long-term obstruction of the seminal tract may cause impaired spermatogenesis, as seen after vasectomy [Thomas Citation1987]. Therefore, the terms/definitions of OA and NOA were not used in this study. Future prospective studies may further clarify the predictive value of ejaculate volume and history of cryptorchidism for the ability to find testicular sperm and for treatment outcome.

Materials and Methods

The diagnosis of azoospermia was verified by examination of at least two ejaculates, which were evaluated untreated and after centrifugation. In this study all non-vasectomized azoospermic men referred to our fertility clinic from December 1997 to December 2009 were included and examined as described below. The study plan was presented for the local scientific ethical committee, which had no objections.

Diagnosing ‘azoospermic couples’ is in practice a running process, which is performed in a systematic way but might be individualized according to particular wishes from each couple. However, in order to analyze the predictive value of single factors for further outcome, we chose to divide the process into four steps: 1) history, clinical, and seminal examination, and determination of serum FSH, 2) genetic examination such as karyotype, Y microdeletions, and CFTR mutations, 3) testicular biopsy for presence of motile sperm and histology, and 4) pregnancy (biochemical and/or clinical) following intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) with testicular or epididymal sperm.

Patients

During the study period 277 men were referred to our clinic for examination due to azoospermia or aspermia. Thirteen couples decided to have intrauterine insemination using donor semen before their examination program was started, and an additional two men were excluded from the study as sperm useful for treatment were in one case found in a new ejaculate, and in the other case sperm were found in postejaculatory urine (as the man suffered from retrograde ejaculation). In total, 262 men were examined by clinical examination and hormonal and genetic analysis as described above. Of these, however, only 203 had a testicular biopsy taken. From six of the remaining 59 men, sperm were observed in new ejaculates before testicular biopsy, and 20 (out of 22) patients with 47,XXY karyotype, 2 (out of 2) with 46,XX karyotype, 1 (out of 1) with a 47,XYY karyotype, and 2 (out of 3) cases with translocations chose not to have a biopsy taken due to the modest chances of finding any sperm. In one case an utricular cyst detected by rectal ultrasonography was resected; one couple had cryopreserved semen, which they chose to use before considering testicular biopsy; in two cases with hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism hormone treatment was started prior to testis biopsy; and in one case the testes were not available for biopsy in spite of several attempts on orchiopexia previously in life. In the remaining 23 (of the 59) cases, non-medical situations were predominantly the causes for non-participation, e.g., divorce of the couple during the relative short time between blood samples and planned testicular biopsy. Twenty men showed ejaculatory dysfunction (anejaculation or retrograde ejaculation) due to tetraplegia, paraplegia, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), or diabetes mellitus of many years, and of these, 14 were completely unable to ejaculate (aspermic).

Examination of ejaculate

Ejaculate volumes were registered, and semen samples were examined for the presence of sperm as described above. The volume of the first delivered ejaculate was used for further analysis.

History and clinical examination

For each participant a detailed history was obtained, and patients were examined by common objective examination (body proportions, hair distribution, and scrotal examination, including palpation for presence of scrotal parts of vasa deferentia) and ultrasonography of the scrotal content. In order to obtain a precise and uniform history and to minimize variation in objective examination all men were examined by the same clinician (JF).

Hormone analysis

Levels of FSH, LH, testosterone, and prolactin were determined using standard techniques. The level of FSH was determined using a commercial electrochemiluminescence immunoassay employing two different monoclonal antibodies (Cobas, Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany).

Genetic analyses

Karyotyping and examination for Y microdeletions and mutations in the CFTR gene mutations was performed as described by Crüger et al. [2003]. At least two specific sequence-tagged sites (STSs) for detection of deletions in each of the three AZFa, AZFb, and AZFc regions were used. Two STSs on Yp and Yq(term) were used as controls. We analyzed for at least four CFTR mutations, which make up more than 90% of the CFTR mutations in ethnical Danes: ΔF508 (exon 10), 394delTT (exon 3), R117H (exon 4) and IVS8-5T (intron 8). In particular cases, including non-ethnical Danes, examination for up to 33 mutations, including IVS8-5T, were performed.

Ultrasonography

Ultrasound examination was used for measuring testicular volumes and examination of echogenicity of the testes. Additionally, non-vasectomized men assumed to suffer from obstructive azoospermia, in many cases had a rectal ultrasonography in order to detect utricular cysts and dilation or absence of the seminal vesicles [Fedder et al. Citation2004].

Testicular biopsy

Following application of funicular blockade with 20 mL Lidokain (lidocaine, SAD), 20 mg/mL injected highly into the scrotum on both sides of the funicle in men with two testicles available, three Tru-Cut biopsies ( i.e., testicular sperm extraction (TESE)) were taken from different parts of one of the testicles. The tissue obtained was used for immediate examination in our IVF-lab, for histological examination and, if the man had given his written consent, often for scientific purposes. If motile sperm were found in the first testicle concomitant with the other testicle being evaluated as normal (without microcalcifications or other signs of Carcinoma in situ testis), in most cases testicular biopsies were only taken on one side. Otherwise testicular biopsies were always taken bilaterally provided that the man had two testicles. Testicular biopsies were cylindrical, 18 mm long (unless the testicle was smaller) and 1.3 mm in diameter (∼24 mm3), each containing more than 100 tubules for evaluation.

Histological examination categorized testicular tissue to one of four groups: 1) normal testis tissue, 2) uniform tissue showing maturation arrest or atrophia, 3) SCO syndrome, or 4) islands (often less than 10%) of normal (or nearly normal) testis tissue in tissue showing SCO syndrome. Histological evaluation was performed independently of clinical history. Testicular tissue was considered normal when all cells representing spermatogenesis (spermatogonia, spermatocytes, spermatids, and spermatozoa) could be detected in the major part of the seminiferous tubules in relative numbers reflecting the mitotic and meiotic divisions the cells undergo through spermatogenesis, and Sertoli cells and peritubular tissue, including Leydig cells, appeared normal.

Statistics

Normally distributed data are presented as means ± SD (range) and compared using Student's t-test. A two-tailed χ2-test with Yates correction was used to compare testicular histological pattern and implantation and live birth rates in relation to history of previous cryptorchidism.

Abbreviations

| CFTR: | = | cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator |

| VD: | = | vasa deferentia |

| FSH: | = | follicular stimulating hormone |

| LH: | = | luteinizing hormone |

| CBAVD: | = | congenital bilateral absence of vasa deferentia |

| CUAVD: | = | congenital unilateral absence of vasa deferentia |

| SCO: | = | Sertoli cell only |

| AMH: | = | anti-Müllerian hormone |

| OA: | = | obstructive azoospermia |

| NOA: | = | non-obstructive azoospermia. |

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges nurse Lone Skovgaard for practical support during the TESEs and molecular biologist Maja Doevling Kaspersen for critical linguistic revision of the manuscript. Also thanks to professor Claus Yding Andersen for constructive criticism of the first manuscript draft.

Declaration of interest: The author has no financial or personal conflicts of interest. The author alone is responsible of the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Crüger DG., Agerholm I., Byriel L., Fedder J., and Bruun-Petersen G. (2003) Genetic analysis of males from intracytoplasmic sperm injection couples. Clin Genet 64:198–203.

- de Kretser D.M., Burger H.G., and Hudson B. (1974) The relationship between germinal cells and serum FSH levels in males with infertility. J Clin Endocrinol Metabol 38:787–793.

- Fedder J. and Boesen M. (1998) Effect of a combined GnRH/hCG therapy in boys with undescended testicles: Evaluated in relation to testicular localization within the first week after birth. Arch Androl 40:181–186.

- Fedder J., Crüger D., Østergaard B., and Bruun-Petersen G. (2004) Etiology of azoospermia in 100 consecutive non-vasectomized men. Fertil Steril 82:1463–1465.

- Gonzales G.F. (1989) Functional structure and ultrastructure of seminal vesicles. Arch Androl 22:1–13.

- Goulis D.G., Tsametis C., Iliadou P.K., Polychronou P., Persefoni-Dimitra K., and Tarlatzis B., (2009) Serum inhibin B and anti-Müllerian hormone are not superior to follicle-stimulating hormone as predictors of the presence of sperm in testicular fine-needle aspiration in men with azoospermia. Fertil Steril 91:1279–1284.

- Haimov-Kochman R., Prus D., Farchat M., Bdolah Y., and Hurwitz A. (2010) Reproductive outcome of men with azoospermia due to cryptorchidism using assisted techniques. Int J Androl 33:e139–143.

- Lissens W., Mercier B., Tournaye B., Bonduelle M., Férec C., and Seneca S., (1996) Cystic fibrosis and infertility caused by congenital bilateral absence of the vas deferens and related clinical entities. Hum Reprod 11( suppl 4):55–80.

- Mau-Holzmann U.A. (2005) Somatic chromosomal abnormalities in infertile men and women. Cytogenet Gen Res 111:317–336.

- Negri L., Albani E., DiRocco M., Morreale G., Novara P.,and Levi-Setti P.E. (2003) Testicular sperm extraction in azoospermic men submitted to bilateral orchiopexy. Hum Reprod 18:2534–2539.

- Raman J.D., and Schlegel P.N. (2003) Testicular sperm extraction with intracytoplasmic sperm injection is successful for the treatment of nonobstructive azoospermia associated with cryptorchidism. J Urol 170:1287–1290.

- Seo J.T., and Ko W.-J. (2001) Predictive factors of successful testicular sperm recovery in non-obstructive azoospermia patients. Int J Androl 24:306–310.

- Simoni M., Tûttelmann F., Gromoll J., and Nieschlag E. (2007) Clinical consequences of microdeletions of the Y chromosome: the extended Mûnster experience. Reprod BioMed Online 16:289–303.

- Thomas A.J. (1987) Vasoepididymostomy. Urol Clin North Am 14:527–538.

- Tsujimura A. (2007) Microdissection testicular sperm extraction: Prediction, outcome, and complications. Int J Urol 14:883–889.

- Vernaeve V., Krikilion A., Verheyen G., vanSteirteghem A., Devroey P., and Tournaye H. (2004) Outcome of testicular sperm recovery and ICSI in patients with non-obstructive azoospermia with a history of orchidopexy. Hum Reprod 19:2307–2312.

- von Eckardstein S., Cooper T.G., Rutsch K., Meschede D., Horst J., and Nieschlag E. (2000) Seminal plasma characteristics as indicators of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene mutations in men with obstructive azoospermia. Fertil Steril 73:1226–1231.

- Wohlfahrt-Veje C., Main K.M., and Skakkebæk N.E. (2009) Testicular dysgenesis syndrome: foetal origin of adult reproductive problems. Clin Endocrinol 71:459–465.