Abstract

Objectives:

To assess persistence on SSRIs (most prescribed antidepressants) and associated healthcare costs in a naturalistic setting.

Methods:

For this retrospective cohort study based on a US reimbursement claims database, all adults with a claim for a SSRI (citalopram, escitalopram, fluoxetine, paroxetine or sertraline) related to a diagnosis of depression were included. Patients should have had no previous reimbursement for any antidepressant within the previous 6 months. Non-persistence was defined as failing to renew prescription within 30 days in the 6-month period after the index date.

Results:

In the 45,481 patients included, persistence decreased from 95.5% at 1 month, to 52.6% at 2 months, 37.6% at 3 months and 18.9% at 6 months. Among factors associated with higher 6-month persistence were age 18–34 years, physician’s specialty, treatment with escitalopram, absence of abuse history and psychotropic prescription history. During the 6-month after index date, healthcare costs tended to be higher in non-persistent than in persistent patients although not significantly (RR = 1.05, adjusted p = 0.055).

Conclusion:

Despite some limitations associated with the use of computerized administrative claims data (residual unmeasured confounding), these results highlight a generally low persistence rate at 6 months. Special attention should be given to persistence on treatment, with consideration of potential antidepressant impact.

Introduction

During the past 15 years, the use of psychotropic drugs has remained relatively constant, while that of antidepressants (ADs) has shown a three- to four-fold increase in the US and other developed countriesCitation1–6. This resulted in a treatment prevalence reaching 8–10% of the US population and an associated total cost of $83 billion in 2000Citation1,Citation2,Citation7. As a consequence, controlling the costs associated with AD treatments has become an increasingly important issue.

In addition to better recognition and increased awareness of the disease, this increased number of AD prescriptions has been related in large part to the introduction of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), which have broad indications and are better tolerated than serotonin-norepinephrin reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) and tricyclic antidepressants (TCA)Citation8. SSRIs are the most frequently prescribed antidepressant and currently represent approximately 70% of prescriptionsCitation9.

Relapse is an important issue in the treatment of major depressive disorders (MDD) and is associated with patient discomfort and increased use of healthcare resourceCitation10,Citation11. To reduce the incidence of relapse, international guidelines for the management of major depressive disorders (MDD) recommend that ADs be continued 4–6 months after symptom remissionCitation12,Citation13. Symptoms of MDD usually disappear within 2–3 months after initiation of an AD treatment, so the duration of AD treatment should be at least 6 months. Nonetheless, several studies have shown a large discrepancy between recommendations and real-life practice, reporting that only one-third of patients use ADs for 6 months or moreCitation14–17.

The authors present here the results of a naturalistic study of the 6-month persistence on SSRIs, and associated use of healthcare resources in the general US population.

Methods

Data source

Data for this retrospective cohort study were extracted from the IMS Lifelink Healthplan database (IMS Health, Watertown, MA, USA), a large US-based longitudinal claims database. It includes data from 86 health plans throughout the US with 45 million patients and over 2.5 billion claim lines.

Data elements in this database include patient demographics, health-plan enrolment information, inpatient and outpatient billing diagnoses and procedures, and outpatient prescription drug dispensing claims. Diagnoses in the medical claims are coded using the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision (ICD-9) codes, procedures by Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) and Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) codes, and prescription drug claims by National Drug Codes (NDC). Claims data from healthcare providers are updated on a monthly basis. Data are formatted for pharmaco-epidemiological analyses and their quality is constantly checked.

Study population

The study population was selected based on the following criteria: (1) adult patients aged 18 years or older at index date, (2) at least one reimbursement claim for one of the following ADs between January 1, 2003 and December 31, 2004: citalopram, escitalopram, fluoxetine, paroxetine or sertraline (first claim within this time window was called index date), (3) at least one diagnosis of depression (i.e., at least one claim associated with an ICD-9 code related to MDD: ICD-9 codes 296.2, 296.3, or another depressive disorder: codes 300.4 and 311.x9) within a period of 1 month before or after the index date, (4) no reimbursement claim for any AD during the 6 months preceding index date, (5) at least 12 months of baseline period before the index date, and (6) at least 18 months of follow-up after the index date.

In case of a gap of more than 90 days in enrolment in the database, only the information available before the gap was considered. Patients were included in the treatment cohort defined by the treatment they had been prescribed at index date. Patients prescribed more than one AD of the five ADs at index date considered were excluded.

Study period

Outcomes were assessed during the 6 months following the index date.

Baseline assessments

Baseline characteristics were assessed during the year prior to the index date and were evaluated by (1) resources used and associated healthcare costs prior to index date (general practitioners [GP] visits, hospitalizations, referrals, anxiolytics, hypnotics, antipsychotics), (2) anxiety co-morbidity (i.e., presence of at least one diagnosis of anxiety), (3) other psychiatric co-morbidities (e.g., alcohol or drug addiction, anorexia, bulimia, compulsive disorder, hysteria, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia) and (4) the Charlson index of comorbidities was calculated on the basis of recorded diagnoses (ICD-9 codes) from a list of 19 diagnoses obtained by medical chart review. The Charlson index assigns a numerical value or ‘weight’ from 1 to 6 for each diagnosis class and a mean weight by patient was calculated.

Outcomes

In accordance with current recommendations, persistence was defined as the duration of time from initiation to discontinuation of the same drugCitation18,Citation19. Reasons for treatment discontinuation (i.e., non-persistence) could be complete stop (non-persistence without switching) or stop with replacement by another AD (non-persistence with switching). Allowing a 30-day grey period to account for irregularities, non-persistence without switching occurred with the first treatment gap lasting more than 30 days, with no evidence of switch. Non-persistence with switching was defined as the first treatment gap lasting more than 30 days, with evidence of a new and other treatment within the month preceding or following discontinuation of the initial AD, and without evidence of a combination between both ADs. Persistence was assessed over the 6-month follow-up period after index date and persistence rates were assessed at 2 and 6 months.

Healthcare resource use and associated costs were assessed over the 6 months following index date. The study uses data from 2003 and 2004, it can thus be hypothesized that the value of the US dollar remained stable over these 2 years. Consequently, healthcare costs were expressed in 2003 or 2004 US dollars as recorded in the database.

Statistical analyses

Categorical variables were expressed as frequency and percentage; groups were compared using the chi-squared or Fisher’s exact tests. Normally distributed quantitative data were expressed as mean and standard deviation (SD); groups were compared using Student’s t-test.

Time to non-persistence within 6 months was evaluated using the Cox proportional hazard model and illustrated by Kaplan–Meier curves. The probability of persistence at 6 months was also estimated by stepwise descending multivariate logistic regression.

Because costs do not have normal distribution, they were compared using univariate generalized linear models (GLM) with log link and gamma distribution. Total direct healthcare costs were also compared using multivariate generalized linear model (GLM) regression with log link and gamma distribution. All regressions were adjusted on the following covariates: (1) patient demographics (i.e., age, gender, insurance plan, prescriber characteristics and region), (2) somatic co-morbidities (Charlson index of comorbidity), (3) psychiatric co-morbidities, (4) previous psychiatric history, and (5) baseline medical resource consumption. The latter variable included psychotropic drug history including ADs (12 months prior to the index date), number of co-treatments at baseline (anxiolytics, antipsychotic, hypnotics, analgesics, antiepileptic, other prescriptions) and total costs during the 12 months prior to the index date.

Results

Patient persistence

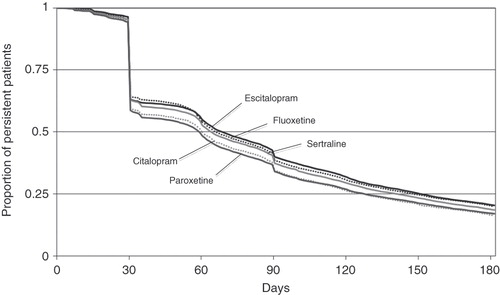

A total of 45,481 patients were included. Initial treatment was citalopram for 3,624 patients (8%), escitalopram for 13,727 patients (30%), fluoxetine for 9,401 (21%) patients, sertraline for 11,327 patients (25%) and paroxetine for 7,402 patients (16%). Although the proportion of users persistent on index AD treatment was high at 1 month (95.5%), this figure decreased to 52.6% at 2 months, 37.6% at 3 months and 18.9% at 6 months (). Persistence at 6 months depended on the AD used (p < 0.001). Escitalopram patients were the most persistent (20.4% at 6 months). They were followed by fluoxetine patients (19.9%), sertraline patients (18.5%), paroxetine patients (17.0%) and citalopram patients (16.2%). The higher persistence observed with escitalopram was due to a lower rate of treatment stop (73.4%). This rate was 74.3% with fluoxetine, 75.9% with sertraline, 76.0% with citalopram and 76.3% with paroxetine. The remaining proportion of non-persistence was due to treatment switching, which was highest with citalopram (7.8%) and lowest with sertraline (5.6%).

Figure 1. Kaplan–Meier estimates of persistence with escitalopram, citalopram, fluoxetine, sertraline and paroxetine.

Univariate comparison of persistent and non-persistent patients showed differences in their baseline characteristics (). In particular, non-persistent patients were younger (mean ± SD = 40.6 ± 13.0 vs. 43.5 ± 12.2 for persistent patients, p < 0.001), a higher proportion lived in the Northeast or in the West, their healthcare plan was more frequently health maintenance organization (HMO) and less frequently preferred provider organization (PPO) or point of service (POS), and their type of payer was less frequently commercial and more frequently Medicaid or self insurance. Nonetheless, persistent and non-persistent patients had a similar gender distribution (71% female), Charlson comorbidity index (0.47 vs. 0.48) and incidence of anxiety at index date (17.4 vs. 18.1%).

Table 1. Patient baseline characteristics.

Factors associated with non-persistence

Multivariate analysis of the variables associated with non-persistence confirmed the differences observed between individual ADs (). Escitalopram patients were significantly more persistent at 6 months after the index date than sertraline (HR = 1.03 [1.01; 1.06]), paroxetine (HR = 1.09 [1.05; 1.12]) or citalopram users (HR = 1.10 [1.06; 1.15]). It also confirmed the association of non-persistence with lower age, type of healthcare plan, type of payer and region of residence. In addition, multivariate analysis showed that non-persistence was associated with drug abuse before index date (HR = 1.13 [1.08; 1.17]), alcohol-related disorders before index date (HR = 1.14 [1.06; 1.23]) and previous prescription of opioids (HR = 1.11 [1.07; 1.16]), anti-inflammatory (HR = 1.06 [1.03; 1.08]), hypnotics (HR = 1.07 [1.03; 1.11]) and antianxiety (HR = 1.08 [1.05; 1.11]) and antipsychotic drugs (HR = 1.11 [1.06; 1.17]).

Table 2. Multivariate analysis of the variables associated with non-persistence at 6 months after index date: Cox model, analysis of maximum likelihood estimates.

Healthcare costs

During the 12 months preceding index date (i.e., before AD prescription), the mean monthly cost for use of healthcare resource was of $500.8 ± 1,493 (). With a monthly mean of $567.5 ± 2,239, citalopram patients had the highest baseline costs. Then followed sertraline patients ($533.6 ± 1,558), paroxetine patients ($510.8 ± 1,440), escitalopram patients ($495.0 ± 1,353) and fluoxetine patients ($436.3 ± 1,270). Total baseline healthcare costs were not significantly different according to the persistent/non-persistent status (p = 0.13) ().

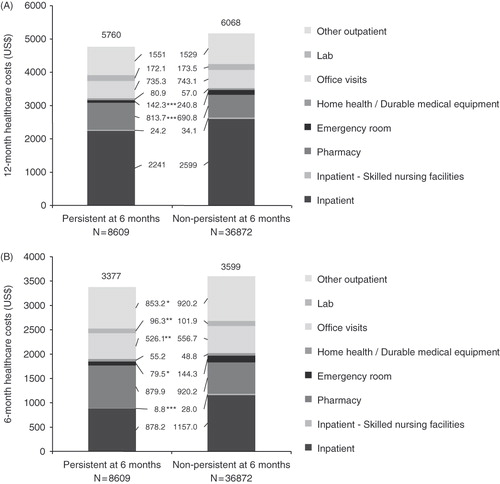

Figure 2. Healthcare costs (2003–2004 US$) (A) at baseline and (B) over the 6 months after the index date according to persistence status at 6 months after index date. Univariate statistical significance: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

During the 6 months following the index AD prescription, the monthly mean cost of healthcare resource use was $592.8, suggesting that individuals starting a new episode of depression have a higher overall cost of healthcare. Over the 6-month period, healthcare costs were $3,377 for persistent AD patients and $3,599 for non-persistent patients (p = 0.07) (). Non-persistent patients had significantly higher costs for skilled nursing facilities, emergency room, office visits, lab and other outpatient healthcare ().

As for persistence, costs varied according to the type of AD used. The 6-month healthcare costs in escitalopram users ($3,517 ± 11,424) were not significantly different from fluoxetine ($3,089 ± 8,881, p = 0.56) and citalopram users ($3,749 ± 10,179, p = 0.39), but were significantly lower than for sertraline ($3,721 ± 9,933, p = 0.02) and paroxetine ($3,880 ± 12,337, p = 0.004).

Factors associated with healthcare costs after index date ()

Multivariate analysis of the variables associated with costs after index date confirmed this strong trend towards higher healthcare costs in non-persistent patients (RR = 1.05, 95% CI [1.00; 1.11], p = 0.055). In addition, this analysis showed that healthcare costs varied according to the AD delivered at index date. Paroxetine and sertraline were associated with higher healthcare costs after index date than escitalopram (respectively RR = 1.08 [1.01; 1.15], p = 0.02 and RR = 1.09 [1.03; 1.15], p = 0.004), which was not observed with citalopram (RR = 1.04 [0.95; 1.13], p = 0.40) or fluoxetine (RR = 1.02 [0.96; 1.08], p = 056). Other variables associated with increased healthcare costs were co-morbidities (especially psychiatric co-morbidities), baseline drug prescriptions, age, type of physician, type of healthcare plan and type of payer.

Table 3. Multivariate analysis of the variables associated with total healthcare costs (2003–2004 US$) after index date: generalized linear model (GLM) regression with log link and gamma distribution.

Discussion

This study shows that persistence at 6 months after initiation of an antidepressant treatment was observed for a low proportion of patients. Analyses indicated that non-persistence was associated with increased healthcare costs.

As recommended by international guidelines, the use of ADs for the treatment of MDD should last 6 months or more, without significant treatment interruptionCitation12,Citation13. This is the reason why this period of time was used for definition of persistence. In the present study, 33% of AD users demonstrated persistence for 1 month or less, 3 months or less in 60% of patients and 6 months or more in fewer than 20% of patients. The substantial decrease in persistence observed after the first month is common for chronic illness therapies, such as cardiovascular medicine, although to a lesser degreeCitation20. These figures confirm results from other studies that show a discrepancy between international recommendations and real-life use of ADs for the treatment of MDDCitation14–17,Citation21–23. These figures also confirm results of the recent database study by Esposito et al who observed better persistence with escitalopram, compared with other SSRIs (i.e., citalopram, fluoxetine, and paroxetine)Citation24. Although the proportion of persistent patients observed at 6 months (20%) was half that described by Esposito et al (44%), this apparent discrepancy is most probably related to the stricter definition of persistence used here, which conforms more to current recommendationsCitation17,Citation18.

In the present study, persistence was evaluated based on reimbursement claims data, which is a reflection of drug purchase. Patients with a permissible gap of more than 1 consecutive month in their reimbursement claim were included in the non-persistent cohort. These data are not an estimation of compliance, which would have needed additional specific study with access to physicians and patients. Nonetheless, in view of the very high level of non-adherence observed with psychotropic drugs and the subsequently high proportion of patients who do not reach the minimal required adequate dosage, one can estimate that the proportion of patients who received adequate AD treatment was again slightly lower than 20%Citation22.

Analysis of the variables associated with non-persistence further increases weight of this data. Indeed, some variables, such as drug abuse and alcohol-related disorders, suggest more severe or complex conditions in non-persistent users. Moreover, the variable most strongly associated with non-persistence was previous AD prescription, which most probably reflects recurrent MDD. In patients with an AD prescription filled 6–12 months before the index date, the rate of non-persistence increased from 33–46%. Studies are not homogeneous in their conclusion about a link between recurrence of depression and non-adherence. Whereas some showed higher 6-month compliance with treatment in recurrent patients, the data presented here support other studies showing that recurrent patients are less adherent to AD treatmentCitation21,Citation25,Citation26. Cohort studies including depression score rating, psychiatric co-morbidities and direct measurement of persistence, among other variables, could help clarify the precise nature and strength of the association that was observed between recurrent depression and non-persistence on AD treatment.

These data also support higher healthcare costs on average are incurred in patients following the onset of a new depressive episode, as evidenced by the average monthly costs of $501 prior to index date, and afterward, $593. Analysis of the impact of persistence on healthcare costs indicated that non-persistent AD users had higher healthcare costs than persistent users. On average, costs were $222 (+6.5%) higher per 6 months in non-persistent patients. This corresponds to an additional cost of more than $16 million per year, if applied to all of the non-persistent patients (36,872) included in the study. The database that was used for this study collects data for more than 45 million people in the US. Applied to the whole US population, the increased cost associated with non-persistence in adults with both a diagnosis of depression and incident AD prescription (i.e., no previous AD prescription during the past 6 months) can be estimated at $100 million per year. In a more speculative way, this increased cost may also be applied to the whole population of AD users in the US, regardless of their age, coverage by a healthcare insurance or history of AD prescription. In 2000, direct medical costs of depression were estimated at $26.1 billion in the USCitation7. Therefore, an increase of 6.5% of these costs in non-persistent patients would correspond to an increased cost of approximately $1.7 billion per year.

However, increased costs can also be attributed to other factors. This is illustrated by the multivariate analyses, which showed that age, physician’s specialty, type of healthcare plan, type of payer, region of residence, drug or alcohol abuse, number of previous prescriptions and previous prescription of psychotropic or analgesic drugs were associated with both non-persistence and increased costs. These data support previous studies showing the effect of socio-demographic and medical variables on healthcare costs in AD usersCitation23. In addition, adverse reactions and subjective factors, such as perception of the efficacy, which influence real-life effectiveness of and adherence to AD treatments, could not be considered in this studyCitation22,Citation23,Citation27. These factors may also explain some of the differences that were observed between drugs with regards to patients’ baseline characteristics and persistence on treatment.

As for persistence, healthcare costs varied according to the type of AD used. Escitalopram was associated with higher 6-month persistence than citalopram, paroxetine and sertraline, and lower 6-month healthcare costs than paroxetine and sertraline. The observation that paroxetine and sertraline were associated with both poorer persistence and higher direct healthcare costs supports the association between persistence and costs.

Despite poorer persistence, citalopram was associated with the lowest cost increase between baseline and follow-up. This may be due to the fact that citalopram patients had the highest baseline healthcare costs. Post-baseline healthcare costs were, therefore, less likely to increase in these patients. This suggests a particular medical profile for these patients. Their lower proportion of anxiety at the index date, indicating less severe depression, supports this hypothesis.

In clinical trials, escitalopram has shown higher efficacy than other SSRIs, especially in severe depressionCitation28–33. Furthermore, it was shown in real-life settings that escitalopram is associated with both increased persistence and lower healthcare costsCitation34–36. However, these studies were restricted to elderly people and no real-life, general population, data were available. Results of the present study confirm the previously reported good ranking of escitalopram regarding persistence and healthcare costs in a real-life general population setting. Escitalopram being more effective in more severe depression, it would have been interesting to describe persistence and healthcare costs according to depression severity but this variable was not available from the database.

This question illustrates the major limitation of performing studies with reimbursement claim databases: unmeasured confounding. As a consequence, residual confounders such as unrecorded baseline differences could not be taken into account. Diagnoses are not based on standard clinical assessments and are recorded in the database for administrative purposes, and the possibility of wrong diagnoses is not null. This is the reason for not excluding bipolar and compulsive disorders but rather use them as covariate. This also could account for some of the very low treatment durations. Similarly, no data about indirect costs (e.g., due to absenteeism) could be collected here. Field studies with access to physicians and patients would be of interest in the analysis of the factors associated with non-persistence and increased healthcare costs. Use of such cohorts would also enable the inclusion of AD patients without health insurance, who probably have different persistence and cost profiles.

In spite of these intrinsic limitations, use of reimbursement claims database has many advantages. The most important of these is the possibility of performing prospective and/or retrospective data collection over a large period of time, without memorization bias. Another strength resides in the size of this database, which represents more than one in seven US residents, distributed throughout the country. Finally, collecting reimbursement claims rather than prescription data allows us to exclude patients who were prescribed ADs but never filled the prescription. This does not avoid poor compliance but is preferred to only prescription data.

Conclusions

The present results confirm a generally poor persistence on antidepressant treatment at 6 months and shows that non-persistence is associated with increased healthcare costs. These data, in addition to other published evidence demonstrating the association between non-persistence and relapse and/or recurrence, and subsequent debilitating symptoms, social impairment and decreased quality of life, highlight the need for an increased consideration of the persistence on AD treatment. This may be achieved by improved communication between physicians and pharmacists, and from these to patients.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was funded by H. Lundbeck A/S, France.

Declaration of financial/other interest

L.F. has disclosed that he is a consultant to H. Lundbeck A/S and has also received lecture fees from H. Lundbeck A/S. D.S., N.D., K.H. and C.F. have disclosed that are employees of H. Lundbeck A/S. K.M. has disclosed that he has received consultancy fees from H.Lundbeck A/S.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the editorial assistance of Guillaume Hébert, PhD, in the research and production of this manuscript.

References

- Mojtabai R. Increase in antidepressant medication in the US adult population between 1990 and 2003. Psychother Psychosom 2008;77:83-92

- Paulose-Ram R, Safran MA, Jonas BS, et al. Trends in psychotropic medication use among U.S. adults. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2007;16:560-570

- Beck CA, Patten SB, Williams JV, et al. Antidepressant utilization in Canada. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2005;40:799-807

- Brugha TS, Bebbington PE, Singleton N, et al. Trends in service use and treatment for mental disorders in adults throughout Great Britain. Br J Psychiatry 2004;185:378-384

- Hall WD, Mant A, Mitchell PB, et al. Association between antidepressant prescribing and suicide in Australia, 1991-2000: trend analysis. BMJ 2003;326:1008

- Olfson M, Marcus SC, Druss B, et al. National trends in the outpatient treatment of depression. JAMA 2002;287:203-209

- Greenberg PE, Kessler RC, Birnbaum HG, et al. The economic burden of depression in the United States: how did it change between 1990 and 2000? J Clin Psychiatry 2003;64:1465-1475

- Isacsson G, Boethius G, Henriksson S, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors have broadened the utilisation of antidepressant treatment in accordance with recommendations. Findings from a Swedish prescription database. J Affect Disord 1999;53:15-22

- Milea D, Verpillat P, Guelfucci F, et al. Prescription patterns of antidepressants: findings from a US claims database. Curr Med Res Opin 2010;26:1343-1353

- Greenberg P, Corey-Lisle PK, Birnbaum H, et al. Economic implications of treatment-resistant depression among employees. Pharmacoeconomics 2004;22:363-373

- Simon GE, Revicki D, Heiligenstein J, et al. Recovery from depression, work productivity, and health care costs among primary care patients. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2000;22:153-162

- Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder revision. American Psychiatric Association. Am J Psychiatry 2000;157:1-45

- NICE (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence). Depression: Management of depression in primary and secondary care. National Clinical Practice Guideline Number 23 amended. 2007

- Gichangi A, Andersen M, Kragstrup J, et al. Analysing duration of episodes of pharmacological care: an example of antidepressant use in Danish general practice. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2006;15:167-177

- Olie JP, Elomari F, Spadone C, et al. Antidepressants consumption in the global population in France. Encephale 2002;28:411-417

- Pietraru C, Barbui C, Poggio L, et al. Antidepressant drug prescribing in Italy, 2000: analysis of a general practice database. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2001;57:605-609

- Sheehan DV, Keene MS, Eaddy M, et al. Differences in medication adherence and healthcare resource utilization patterns: older versus newer antidepressant agents in patients with depression and/or anxiety disorders. CNS Drugs 2008;22:963-973

- Cramer JA, Roy A, Burrell A, et al. Medication compliance and persistence: terminology and definitions. Value Health 2008;11:44-47

- Peterson AM, Nau DP, Cramer JA, et al. A checklist for medication compliance and persistence studies using retrospective databases. Value Health 2007;10:3-12

- Foody JM, Joyce AT, Rudolph AE, et al. Persistence of atorvastatin and simvastatin among patients with and without prior cardiovascular diseases: a US managed care study. Curr Med Res Opin 2008;24:1987-2000

- Bockting CL, ten Doesschate MC, Spijker J, et al. Continuation and maintenance use of antidepressants in recurrent depression. Psychother Psychosom 2008;77:17-26

- Hansen HV, Kessing LV. Adherence to antidepressant treatment. Expert Rev Neurother 2007;7:57-62

- Trivedi MH, Lin EH, Katon WJ. Consensus recommendations for improving adherence, self-management, and outcomes in patients with depression. CNS Spectr 2007;12:1-27

- Esposito D, Wahl P, Daniel G, et al. Results of a retrospective claims database analysis of differences in antidepressant treatment persistence associated with escitalopram and other selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in the United States. Clin Ther 2009;31:644-656

- Demyttenaere K, Adelin A, Patrick M, et al. Six-month compliance with antidepressant medication in the treatment of major depressive disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2008;23:36-42

- ten Doesschate MC, Bockting CL, Schene AH. Adherence to continuation and maintenance antidepressant use in recurrent depression. J Affect Disord 2009;115:167-170

- Machado M, Iskedjian M, Ruiz I, et al. Remission, dropouts, and adverse drug reaction rates in major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of head-to-head trials. Curr Med Res Opin 2006;22:1825-1837

- Boulenger JP, Huusom AK, Florea I, et al. A comparative study of the efficacy of long-term treatment with escitalopram and paroxetine in severely depressed patients. Curr Med Res Opin 2006;22:1331-1341

- Kennedy SH, Andersen HF, Lam RW. Efficacy of escitalopram in the treatment of major depressive disorder compared with conventional selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and venlafaxine XR: a meta-analysis. J Psychiatry Neurosci 2006;31:122-131

- Lam RW, Andersen HF. The influence of baseline severity on efficacy of escitalopram and citalopram in the treatment of major depressive disorder: an extended analysis. Pharmacopsychiatry 2006;39:180-184

- Llorca PM, Azorin JM, Despiegel N, et al. Efficacy of escitalopram in patients with severe depression: a pooled analysis. Int J Clin Pract 2005;59:268-275

- Montgomery SA, Baldwin DS, Blier P, et al. Which antidepressants have demonstrated superior efficacy? A review of the evidence. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2007;22:323-329

- Moore N, Verdoux H, Fantino B. Prospective, multicentre, randomized, double-blind study of the efficacy of escitalopram versus citalopram in outpatient treatment of major depressive disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2005;20:131-137

- Tournier M, Moride Y, Crott R, et al. Economic impact of non-persistence to antidepressant therapy in the Quebec community-dwelling elderly population. J Affect Disord 2009;115:160-166

- Wu E, Greenberg P, Yang E, et al. Comparison of treatment persistence, hospital utilization and costs among major depressive disorder geriatric patients treated with escitalopram versus other SSRI/SNRI antidepressants. Curr Med Res Opin 2008;24:2805-2813

- Wu E, Greenberg PE, Yang E, et al. Comparison of escitalopram versus citalopram for the treatment of major depressive disorder in a geriatric population. Curr Med Res Opin 2008;24:2587-2595