Abstract

Objective:

To determine the incremental cost of healthcare and clinical outcomes in the 12 months following incident hip fractures among postmenopausal women in the UK.

Methods:

Retrospective cohort study of women aged 50 years or older hospitalized for an incident hip fracture within 1 week of the fracture date who were age- and comorbidity-matched to women without fracture. Cohorts were identified in the Health Improvement Network database, and followed up for 1 year.

Results:

Among 2,427 women who had a hip fracture and a recorded hospitalization, the mean [SD] age was 81 [9.3] years. About 18% of women without fractures were hospitalized during follow-up and 18% of women with hip fractures and 4% of women without fractures had at least one emergency admission (RR, 4.7; 95% CI, 3.8–5.8). There were no major differences in use of general practitioner visit, referral visits, or in prescription of medications. Mortality was 18% in the hip fracture cohort and 7% in the non-fracture cohort (RR, 2.5; 95% CI, 2.1–3.0). The overall 1-year mean incremental cost of hip fractures was £4,222 (95% CI, £4,105–4,339); most of this cost (97%) was for hospitalizations, with an increment of £4,095. About 98% of the incremental cost occurred in the first 6 months following hip fracture.

Conclusions:

The results of this study indicate that the cost and clinical burden associated with hip fractures in postmenopausal women in the UK are considerable. The incremental cost is mostly related to the cost of hospitalization and treatment of the hip fracture. Key limitations were the inclusion of only those women with a recorded hospitalization, and that costs associated with rehabilitation services, social services, and long-term care were not recorded in this study, although these are important contributors to the total cost of fractures.

Key words::

Introduction

Osteoporosis-related fractures are a major cause of morbidity in the elderly and place a large medical and economic burden on the healthcare system. The rapid bone loss associated with the decrease in circulating estrogens that characterizes menopause places women at a particularly high risk of osteoporosis, with a resulting increase in bone fragility and hence susceptibility to fracturesCitation1.

The annual number of osteoporotic fractures is expected to increase due to the rapid growth rate of the elderly population worldwideCitation2. For white women, the one-in-six lifetime risk of sustaining a hip fracture is greater than the one-in-nine risk of developing breast cancerCitation3. Hip fracture is a serious and costly injury, and as the United Kingdom (UK) population ages, the incidence will rise from approximately 70,000 cases per year at present to approximately 100,000 cases per year by 2020Citation4. The impact of hip fracture on patients’ lives can be considerable, not only in terms of the associated morbidity and disability, diminished quality of life, and mortality, but also in terms of incurring medical care costs.

Studies evaluating the clinical and economic burden of hip fractures in a population of postmenopausal women will help to assess the impact of these fractures on the overall health status of women and the associated utilization of healthcare resources, including the impact on different cost components (i.e., hospitalization, outpatient care, disability, and premature death). Compared with other published studies, this study used a population-based approach and included a large, representative sample of women with and without hip fractures from the general population in the UK to estimate the incremental cost of these fractures.

The work presented here is part of a larger project that assessed the clinical and economic burden of various types of fractures among postmenopausal women aged 50 years or older in a UK general population setting. The goal of the study was to determine the incremental cost of care associated with the clinical consequences and healthcare resource utilization of specific fracture types in the study population. This paper presents the analysis and results associated with the occurrence of hip fractures.

Patients and methods

Study design and source population

In this retrospective cohort study, a cohort of women were identified with a diagnosis of a hip fracture and a corresponding age- and comorbidity-matched non-fracture cohort from a population of postmenopausal women (aged 50 years or older) registered with a general practitioner (GP) and with health information accessible through The Health Improvement Network (THIN) research database. General practitioners in the UK are the gate keepers of the healthcare system and are responsible for primary healthcare and specialist referrals. The population of patients registered in the THIN database is known to represent approximately 4% of the general population in the UK. The THIN database contains diagnostic and prescribing information recorded by GPs as part of their routine clinical practice. Data are recorded using READ Codes which consist of a hierarchically-arranged comprehensive list of clinical terms to describe the care and treatment of patients in general practice. Approval for this study was obtained from the South East Multi-centre Research Ethics Committee in accordance with THIN requirements. All data supplied by THIN were anonymized, with the identities of patients and practices fully protected. The data accrued included demographic information, GP visits, prescription details, referral to specialist care, accident and emergency (A&E) visits, hospital admissions, and clinical events of interest.

Study population

The study population consisted of all women aged 50 years or older who had a minimum of 12 months of continuous enrollment in a general medical practice that contributed data to the THIN database. This period of at least 12 months was required to eliminate prior fractures during this time and to gather data on concurrent comorbidities. The study period considered for analyses ran from January 1, 2001 to December 31, 2005.

Study cohorts

The hip fracture cohort consisted of all eligible women in the study population with a first recorded hospitalization for a closed hip fracture, with continuous enrollment in their general medical practice for at least 12 months prior to the date of fracture and who had not had a fracture of any type during the 12 months before the date of the fracture (index date). This first incident fracture was considered as the index fracture. Hip fracture cases were identified and defined by READ codes compatible with the diagnosis and/or treatment of hip fracture.

These READ codes used to identify incident hip fractures did not necessarily imply that a hospitalization occurred. Therefore, the index hip fracture was deemed to be associated with a hospitalization if there were any hospitalization record on index date or in the 1 week following the index fracture.

For a given hip fracture case, the matched control (to be included in the non-fracture cohort) was identified from all eligible women in the study population that had continuous enrollment in their general medical practice for at least 12 months prior to the calendar index date of the hip fracture case. As in the fractures cohort, women in the non-fractures cohort were required to be free of any fracture during the 12 months prior the index date. However, women in the non-fracture cohort who developed a fracture during follow-up were allowed to become eligible for the fracture cohort. The follow-up start date for both hip fracture cases and their matched control in the non-fracture cohort was the same calendar date.

Study follow-up period

For each woman in the hip fracture cohort, the follow-up start date was the index date, i.e. the date of the first recorded (and eligible) hip fracture occurring between January 1, 2001 and December 31, 2005. For women in the non-fracture cohort, the follow-up start date was the same calendar date as for the corresponding matched hip fracture case.

The hip fracture and non-fracture cohorts were followed from the start follow-up date to the earliest of any of the following times and/or events: 1 year after start date, death, or end of enrollment from the general medical practice. In addition, in the non-fracture cohort, follow-up ended at the date of occurrence of any fracture (n = 77).

Matching and assessment of comorbidity

Individual one-to-one matching of women in the non-fracture cohort to women in the hip fracture cohort was based upon age (±2 years), general medical practice, and comorbidity score. Matching also accounted for the length of the preindex period (±2 years). The preindex period was the time from THIN enrollment to the follow-up start date, where follow-up start date was the date of the hip fracture in the fracture cohort and same calendar date in the matched cohort. Matching on the preindex period enabled periods of comorbidity ascertainment to be of similar duration across the study cohorts. The Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) score was used to ensure a similar burden of baseline comorbidities of women across the study cohortsCitation5. The analyses were performed by weighting patient comorbidity profiles using Charlson’s suggested weights, and matching was accomplished according to the CCI score groups, i.e., CCI = 0, CCI = 1 or 2, CCI = 3–5, and CCI = 6 or higher.

Healthcare utilization and clinical outcomes

To derive cost estimates associated with healthcare resource utilization, data on the frequency of hospitalizations were evaluated, as well as A&E visits, GP visits, specialists’ referrals, and prescription of medications, separately for the hip fracture and the non-fracture cohorts. The evaluation of clinical endpoints included the occurrence of subsequent fractures and deaths. Subsequent fractures in the hip fracture cohort were defined as a diagnosis of any bone fracture at sites distinct from the hip fracture site and occurring at any time during study follow-up. Determinations of whether a patient died and the date of death were made using an algorithm in which deaths were identified using three sources (READ codes matching the death code, registration status ‘99’ and additional health data codes).

It was assumed that the medical management and treatment of hip fractures require that the patient be hospitalized. In the THIN database, GPs keep record of hospitalizations based on data from the hospital discharge letter. To ascertain hospitalizations, an algorithm was developed that incorporated the following sequential steps: (1) use of the SOURCE variable, which provides the origin of the computerized record, and the ‘LOCATE’ variable, which provides the location of the consultation that gave rise to the record, (2) use of the specific READ terms that indicated hospitalization after review of the list of general hospital admissions and referral terms and then selection of only those READ terms that strongly indicated a hospitalization, (3) examination of the READ terms recorded in the study cohort that were associated with the relevant SOURCE and LOCATE codes, and (4) once potential hospitalizations were identified, all the computerized records for each woman were manually reviewed to confirm the hospitalization and to assign the date and cause of hospitalization.

Cost estimates

Hospitalization costs were assigned using Healthcare Resource Group (HRG) codes. Each hospitalization had a separate cost based on the associated READ code. The average hospitalization cost applied for hip fracture READ codes was approximately £2,950. The source of the UK hospitalization costs was the Non-elective/Elective episode data in the NHS Reference Costs 2006–2007Citation6. NHS Reference Costs was also used to obtain the national average cost for an A&E visit cost. Reason for A&E visit was not used to separately cost A&E visits. A UK national average cost associated with a GP consultation was available from the Personal Social Services Research Unit (PSSRU)Citation7. This unit cost was applied to each GP visit in the THIN database and the reason for a GP visit was not used for costing purposes. Specialist referral costs were applied using the NHS Reference Costs associated with the national average unit costs per first outpatient consultation for the specific referral specialty. Prescription costs were applied using the British National Formula (BNF) descriptions for the prescribed treatments. For all types of resource use, unit costs for 2007 were used wherever possible. Where 2007 costs were unavailable, the most recent available costs were used and their source and year recorded in the report.

Total costs and costs by resource use type were summarized and compared by cohort. Three time periods after the start date were considered for the cost analyses: the first 6 months (from start date to day 180), the second 6 months (from day 181 to day 365), and the overall 1-year period (from start date to day 365).

Statistical analysis

Data analyses were performed using SAS version 9.1Citation8. Before conducting any analyses, complete and validated analysis datasets were created that contained all derived variables. These datasets comprised cost data applied to the individual resource use items and contained one row per patient. Absence of clinical records was assumed to indicate that healthcare resources were not used.

Among women with a hip fracture and with a recorded hip fracture-related hospitalization occurring within the first week following the index date, the 1-year incremental effect and associated 95% confidence interval (CI), versus the matched non-fracture cohort was estimated. The incremental effect of hip fracture on the primary endpoint was estimated, as well as total cost, and all other variables. For continuous variables, the incremental effect was calculated as the difference between means (MD). For categorical variables, the incremental effect was calculated as the relative risk (RR).

For all continuous outcomes, summaries were produced by cohort to include a mean, standard deviation (SD), median, minimum, and maximum. For categorical outcomes, summaries were produced by cohort to include cell counts and percentages.

As cost data are notorious for being skewed bootstrapped incremental costs were produced as a sensitivity analysis to the parametric estimates. There were no differences of note and therefore the parametric estimates in this paper are presented.

Results

During the study period, 2,427 women aged 50 years and older were identified who had a diagnosis of an incident hip fracture and who had a hip fracture-related hospitalization (hip fracture cohort) and an equal number of age- and comorbidity-matched women without a fracture (non-fracture cohort).

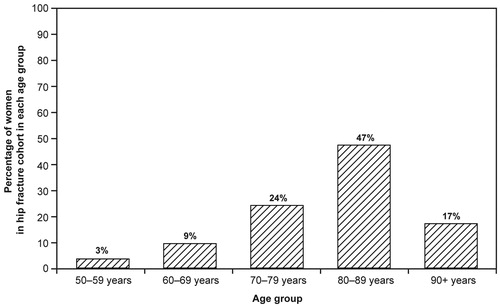

Matching of women with a hip fracture and women without fractures was accomplished successfully in 97.5% of cases. Unmatched cases were excluded from the analyses, and no systematic differences between matched and unmatched women were identified. The mean age of women in both cohorts was 81 years (SD, 9.3) and the mean CCI score was 1.2 (SD, 1.3). The age distribution of women in the hip fracture cohort at the index date is displayed in . Approximately 87% of women in both cohorts were registered in general practices in England, and the average time since registration was 4.7 years (SD, 2.3). During the period from registration in THIN to the 12 months prior to the study start date, a higher proportion of women in the hip fracture cohort (32%) than in the non-fracture cohort (26%) had a history of any fracture. The average study follow-up time for women in both cohorts was 300 days (median 355 days).

Healthcare resource utilization and clinical outcomes

shows the number of women with at least one medical encounter (i.e., GP visit, referrals, hospitalization, A&E visit, or prescribed medication) during the year following the study start date. By cohort definition, all women in the hip fracture cohort had at least one hospitalization; among women in the non-fracture cohort, 18% were hospitalized during follow-up. Similarly, a higher proportion of women in the hip fracture cohort than in the non-fracture cohort had at least one A&E visit (RR, 4.7; 95% CI, 3.8–5.8). There were no differences between the two cohorts in the proportion of women with at least one visit to their GP or with at least one referral to a specialist. The number of prescribed medications was higher in the hip fracture cohort (MD = 12.3; 95% CI, 9.0–15.7). Among women with a hip fracture, 5% were recorded to have a subsequent fracture during follow-up and the associated costs were included in the total costs for these women. Mortality, evaluated based on the number of recorded deaths during follow-up, was 18% in the hip fracture cohort and 7% in the non-fracture cohort (RR, 2.5; 95% CI, 2.1–3.0).

Table 1. Healthcare resource use and clinical outcomes during the 12 months following start date.

Overall costs and incremental costs by healthcare resource component

summarizes the overall and resource-specific health utilization cost in the hip fracture and non-fracture cohorts. During the full year after the start of follow-up, the average total healthcare resource utilization cost per woman was £5,335 (SD, 2,642) for the hip fracture cohort and £1,113 (SD, 1,270) for the non-fracture cohort. Total cost broken down by the healthcare resource components evaluated in this study indicated that among women with a hip fracture, the highest cost was associated with hospital care. In this cohort, the average hospitalization cost per woman was £4,390, representing 82% of the total cost, and was incurred primarily during the first 6 months following the date of the fracture. The second highest cost was associated with the cost of medications and was £608 per woman, representing 11% of the total cost. In the non-fracture cohort, use of prescription medications was the healthcare resource associated with the highest cost (£501 average cost per woman) and represented 45% of the overall cost.

Table 2. Overall costs by healthcare resource component in women with a hip fracture–related hospitalization over matched controls in the non-fracture cohort.

Estimation of the overall and healthcare resource-specific incremental costs is summarized in . During the full year after the study start date, the overall incremental cost associated with the care of hip fractures was £4,222 per woman over the healthcare cost for women in the non-fracture cohort. Consistent with the results for overall cost, most of the incremental cost was linked to hospitalization (MD = £4,095) and represented 97% of the entire incremental cost. The first 6 months after the start date concentrated most of the incremental cost attributable to the care of women with hip fractures, with a total incremental cost of £4,151.

Table 3. Overall incremental costs, by healthcare resource component, in women with a hip fracture-related – hospitalization over matched controls in the non-fracture cohort.

Discussion

A study was conducted that evaluated the economic and clinical burden of hip fractures among women aged 50 and older in the UK. In this paper are presented the results for the cohort of women who had an incident hip fracture and who were hospitalized, compared with a matched non-fracture cohort. A population-based approach was used based on data collected by GPs in the UK and available through the THIN research database analyzed. This database is a longitudinal primary care database of computerized GP medical records that has been extensively used for research purposes and in epidemiological studies evaluating osteoporosis outcomes (e.g., van Staa et al., 2002; van Staa et al., 2006)Citation9,Citation10. Furthermore, independent studies have shown a high level of completeness and validity of the data collected in THINCitation11. The database has approximately 6 million patients, of whom 2.8 million are registered with THIN practices and can be followed prospectivelyCitation12. The population registered in the THIN database represents nearly 4% of the general population in the UK.

The mean age of women with hip fractures was 81 years, which is in agreement with the epidemiology of hip fractures and with data reported from various studies in the UKCitation13–15. The present study showed an increased mortality of 18% during the first year post-fracture compared to a 7% mortality among women in the non-fracture cohort (RR, 2.5; 95% CI 2.1–3.0). This result is also in line with data from several studies that have shown an increased mortality following hip fractures and that have reported 1-year cumulative mortality rates among elderly women between 20% and 25% in the UKCitation13,Citation16 and AustraliaCitation17.

The cost associated with osteoporotic fractures presents a large economic burden to the UK healthcare system. Evaluation of the economic burden of hip fractures in this study included the costs associated with hospitalization, GP visits, A&E visits, referrals, and prescription medications during the 12 months following the fracture. The study design and methodology used allowed determination of the differences in resource utilization between women in the hip fracture cohort and in the non-fracture cohort, and estimation of the cost attributable to hip fracture, including acute hospitalization (incremental cost). The estimated total mean cost of care for a hip fracture was £5,335 (representing an incremental cost difference of £4,222), which was of a magnitude similar to the costs reported in several other studies. Hospitalization is the largest component of costs associated with care of a hip fracture, and was reported to be £4,390, representing 82% of the total cost per woman in the current study.

The estimates of the cost of care of a hip fracture from the present study can be compared with other estimates from published UK-based studies, as presented in . The published studies were identified through a search of the PubMed database, to identify UK studies reporting the cost of hip fracture. However, this literature search was not a systematic, exhaustive search and the data presented from the identified studies are provided to add context to the current study results. In the current study, the cost of hospitalization referred exclusively to the hospitalization and did not include the cost of inpatient or outpatient rehabilitation. presents the cost derived from the current study without rehabilitation costs, and the estimated cost including rehabilitation, based on an average of rehabilitation costs from previous studies. The published studies varied as to whether they included inpatient rehabilitation costs, or combined inpatient and outpatient rehabilitation costs, so this must be considered when comparing data. In two studies, rehabilitation costs were not presented separately so these were estimated based on the total inpatient costs, and the number of days on a geriatric ward (assumed to be rehabilitation) as a proportion of the total inpatient daysCitation18,Citation19. Previous costs (with or without rehabilitation) have been presented as given in the original sources, without inflating costs to current levels. The available or estimated rehabilitation costs were presented as given in the original sources, as well as being inflated to 2006/2007 levels using the PPSRU (Personal Social Services Unit) Hospital and Community Health Services Pay and Prices Index, to allow an average to be calculated. The total costs for each study were also inflated to 2006/2007 costs to allow comparisons to be made. Where costs have been converted from euros to pounds sterling, exchange rates have been used as cited in the original sources. The total cost of hip fracture in the current study, including the estimated rehabilitation costs, was £9,936, which was of a similar magnitude to the inpatient cost estimates from three published studies (£9,897Citation1Citation8, £8,701Citation1Citation9, and £7,233Citation20; see ). The study by French and colleagues reported a somewhat lower cost of hip fracture, indicating a cost of £5,666, which did not include outpatient rehabilitationCitation21. Conversely, the study by Dolan and Torgerson (1998) reported a much greater cost of hip fracture (£18,146), since this included follow-up, long-term hospital stay, and social care costs (including chiropody, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, social work, health visitor, district nursing, night attendance, laundry, bath attendant, meals, home care, day care, day hospital, respite care, GP domiciliary, GP surgery, and outpatient care)Citation14. Three of the studies in did not present rehabilitation costs separately or provide an estimate of days in a geriatric ward to allow rehabilitation costs to be estimatedCitation15,Citation22,Citation23; however, these studies have been included in for completeness.

Table 4. Overall costs of hip fracture in the UK: current study versus published studies, with and without rehabilitation costs.

Particular aspects of this study need to be taken into account when interpreting the results. The THIN database is a primary care database and although hospitalizations are recorded, there is no standardized approach for recording and identifying hospitalizations, or the reason for hospitalization. To counterbalance these limitations, an algorithm was developed to ascertain hospitalizations and manually reviewed the computerized records of each woman who had a potential hospitalization to confirm the hospitalization and to assign the date and cause of hospitalization. Despite this approach, the proportion of hospitalized women with hip fractures (70%) was lower than expected; as in current clinical practice, virtually all patients who experience a hip fracture in the UK would be hospitalizedCitation19. Therefore, only women who had a recorded hospitalization were included in the final analysis as described in the Methods section. Also, many of the published cost datasets for hip fractures are explicitly linked to cohorts of hospitalized patients. Since it is known that the cost of hospitalization is the main contributor to the cost associated with the care of hip fractures, a 30% underreporting of hospitalizations could have led to a substantially underestimated cost burden. To address this limitation and to thoroughly evaluate the economic burden of women who had a hip fracture, the cost analysis was focused on women who had a hip fracture and a related hospitalization within 1 week of fracture. Data on rehabilitation services, social services, and long-term care are not recorded in THIN; therefore, this study does not provide data on the long-term costs associated with the use of these healthcare resources. These are relevant contributors to the total cost of fractures, and it is worth emphasizing that this study provides data on the healthcare resource costs associated with hospitalizations, GP visits, A&E visits, referrals, and prescription of medications during the 12 months following the date of the fracture. However, based on an average from previous published studies, the costs of outpatient rehabilitation were added to the costs reported in THIN, as reported in .

Conclusions

The results of this study contribute to the existing evidence that indicate that the clinical and economic burden of hip fractures among postmenopausal women is considerable and that hospitalizations account for most of the costs associated with the care of hip fractures during the 1 year following the fracture. Other costs derived from the long-term care of fractures (e.g., rehabilitation, social services, hospice care) were not evaluated in this study and these are important contributors of the total healthcare cost associated with hip fractures.

Additional research in this area is required to investigate the long-term incremental costs of hip fracture. Previously, a study was conducted to investigate the long-term costs of hip fractures, including social care and long-term hospital stayCitation14. However, this study was conducted in 1991–1992 and investigated total costs rather than incremental costs. A more recent study investigating incremental costs is required to reflect more accurately the costs specifically related to hip fracture itself. Incremental costs of other types of fractures, such as vertebral fractures and non-vertebral non-hip fractures, may also be investigated. Due to the rapid growth rate of the elderly population worldwide, the clinical and economic burden of osteoporotic fractures is expected to increase considerably during the next decades. Comprehensive evaluations of the impact of these fractures on patient lives and on societal burden are important to understand the clinical and economic burden of fractures in order to determine the true cost effectiveness of potential new treatments.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was sponsored by Amgen.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

L.G., N.R., J.C., S.B., C.R., S.A., and P.S. are all employees of RTI Health Solutions, which performed this research under contract with Amgen. S.R. and M.G. are employees of Amgen GmbH (Europe).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Cegedim Strategic Data (CSD) EPIC group for providing access to THIN data and for their support.

References

- WHO Study Group on Assessment of Fracture Risk and Its Application to Screening for Postmenopausal Osteoporosis. Assessment of fracture risk and its application to screening for postmenopausal osteoporosis: report of a WHO study group. Technical Report Series No. 843. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1994. Available at: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/trs/WHO_TRS_843.pdf. [Last accessed 6 December 2009]

- Cummings SR, Melton LJ 3rd.. Epidemiology and outcomes of osteoporotic fractures. Lancet 2002;359:1761-7

- Cummings SR, Black DM, Rubin SM. Lifetime risks of hip, Colle’s, or vertebral fracture and coronary heart disease among white postmenopausal women. Arch Intern Med 1989;149:2445-8

- Preliminary national report 2009. London: National Hip Fracture Database, 2009. Available at: http://www.ccad.org.uk/nhfd.nsf/6ec433ed9efaa78e802572e3003a3517/ed40fa45ba9877108025779f0041fbca/$FILE/Preliminary%20National%20Report.pdf. [Last accessed 6 December 2010]

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40:373-83

- NHS reference costs 2006–2007. London: Department of Health, February 2008. Available at: http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_082571. [Last accessed 6 December 2010]

- Curtis L. Unit costs of health and social care 2007. Canterbury, Kent, UK: Personal Social Services Research Unit, University of Kent, 2007. Available at: http://www.pssru.ac.uk/pdf/uc/uc2007/uc2007.pdf. [Last accessed 6 December 2010]

- SAS/STAT software. Version 9 for the SAS System for Windows. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc., 2002–2003

- van Staa TP, Leufkens HGM, Cooper C. Does a fracture at one site predict later fractures at other sites? A British cohort study. Osteoporos Int 2002;13:624-9

- van Staa TP, Geusens P, Kanis JA, et al. A simple clinical score for estimating the long-term risk of fracture in post-menopausal women. Q J Med 2006;99:673-82

- Lewis JD, Schinnar R, Bilker WB, et al. Validation studies of The Health Improvement Network (THIN) database for pharmacoepidemiology research. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2006;16:393-401

- Lo Re III V, Haynes K, Forde KA, et al. Validity of The Health Improvement Network (THIN) for epidemiologic studies of hepatitis C virus infection. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2009;18:807-14

- Beringer TRO, Clarke J, Elliott JRM, et al. Outcome following proximal femoral fracture in Northern Ireland. Ulster Med J 2006;75:200-6

- Dolan P, Torgerson DJ. The cost of treating osteoporosis fractures in the United Kingdom female population. Osteoporos Int 1998;8:611-17

- Lawrence TM, White CT, Wenn R, et al. The current hospital costs of treating hip fractures. Injury 2005;36:88-91

- van Staa TP, Dennison EM, Leufkens HGM, et al. Epidemiology of fractures in England and Wales. Bone 2001;29:517-22

- Center JR, Nguyen TV, Schneider D, et al. Mortality after all major types of osteoporotic fracture in men and women: an observational study. Lancet 1999;353:878-82

- Hollingworth W, Todd C, Parker M, et al. Cost analysis of early discharge after hip fracture. BMJ 1993;307:903-6

- Hollingworth W, Todd CJ, Parker MJ. The cost of treating hip fractures in the twenty-first century. J Public Health Med 1995;17:269-76

- Bouee S, Lafuma A, Fagnani F, et al. Estimation of direct unit costs associated with non-vertebral osteoporotic fractures in five European countries. Rheumatol Int 2006;26:1063-72

- French FH, Torgerson DJ, Porter RW. Cost analysis of fracture of the neck of femur. Age Ageing 1995;24:185-9

- Stevenson MD, Davis SE, Kanis JA. The hospitalisation costs and out-patient costs of fragility fractures. Women’s Health Med 2006;3:149-51

- Finnern HW, Sykes DP. The hospital cost of vertebral fractures in the EU: estimates using national datasets. Osteoporos Int 2003;14:429-36