Abstract

Background:

To evaluate the cost burden of patients with advanced Parkinson’s disease (PD) according to the waking hours per day spent in OFF state. An analysis of resource use comprising medical services, professional care and informal care data from an observational, cross-sectional study was conducted.

Methods:

A total of 60 physicians comprising 40 neurologists and 20 geriatricians across the UK participating in the Adelphi PD Disease Specific Programme took part. There were 302 PD patients at H&Y stages 3–5. Patients were characterised according to the percentage of time per day spent in OFF state (<25%, 26–50%, 51–75%, >75%).

Results:

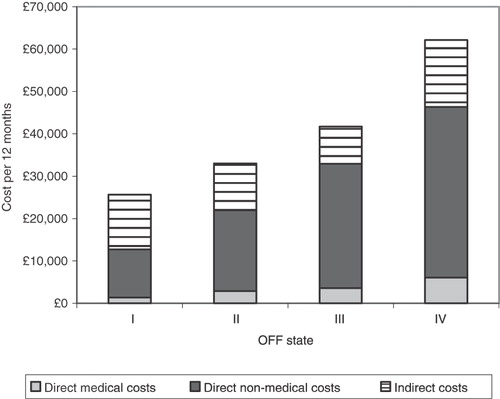

Average 12-monthly total costs increased according to the time spent in OFF state from £25,630 in patients spending less than 25% of their waking hours in OFF to £62,147 for patients spending more than 75% of their time in OFF. Overall, 7% of costs were attributed to direct medical care, while 93% were split between direct non-medical professional care (50%) and indirect informal care (43%).

Limitations:

Low patient numbers in the more advanced disease stages of PD led to very little or no data to directly inform some of the severe health states of the analysis. Data gaps were filled in with data derived from a regression analysis which may affect the robustness of the analysis.

Conclusion:

This study illustrates the increasing costs of advancing PD, in particular related to the time spent in OFF state, and identifies that the foremost cost burden is associated with the care needs of the patient rather than medical services.

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a progressive, chronic neurodegenerative disorder with an estimated prevalence of 100–180 per 100,000 and incidence of 4–20 per 100,000Citation1. The burden of disease in PD is significant and increases as the condition progresses, impacting on patients and their families, the healthcare system and society as a wholeCitation2–10. PD patients require increasing assistance for both medical and social care and rely more and more on family members and carers for help with daily life. They have significantly higher healthcare utilisation and therefore higher healthcare-related costs than non-PD patients. Huse et al.Citation7 reported total direct annual costs (2002 prices) for PD patients in the US as $23,101 versus $11,247 for controls, while Noyes et al.Citation10 reported healthcare expenses of $18,528 for PD versus $10,818 for non-PD patientsCitation7,Citation10. Compared to other neurological diseases such as epilepsy, migraines, multiple sclerosis and stroke, PD is the third-most expensive disease next to multiple sclerosis and stroke on a cost per case basisCitation11. The total annual cost of PD per patient was estimated at £5,993 (1998 prices) comprising £2,298 for treatment costs, the remainder the cost of social services and patients’ private expenditureCitation12. Applying a conservative estimate of PD prevalence in the UK of 58,600 PD patients, the total direct costs amount to £351,200,000 (1998 prices), increasing to £599,300,000 per year if a higher prevalence of 100,000 PD patients was assumedCitation5.

The relationship between PD severity, measured by the Hoehn and Yahr (H&Y) scale, and costs of treatment is well-establishedCitation8,Citation9,Citation13,Citation14. Costs have been estimated to double per each H&Y stage after stage 2Citation8, and were also reported to be higher in patients with motor complications and dyskinesiasCitation4,Citation9,Citation15. The cost of PD is particularly high in the later stages of the disease where considerable amounts of patient care are required. In 2003, Findley et al.Citation12 reported a significant relationship between increasing costs of care and increasing H&Y stage. A six-fold increase in mean annual expenditure was noted between stages H&Y 0/1 and stage 5, from £2,971 to £18,358.

However, the relationship between costs and the amount of time patients spend in OFF state has, to the authors’ knowledge, not been previously demonstrated. All PD patients, regardless of disease severity, can experience OFF state. This phenomenon typically develops after 4–6 years of therapy and is a particularly debilitating aspect of the disease and causes considerable disabilityCitation16. In the OFF state patients can experience tremor, stiffness, slowness of movement, and/or periods of immobility. This can be due to medication wearing off or a reaction to the medication itself and manifests as a re-emergence of PD symptomsCitation17. The objective of this study is to evaluate the resource use of advanced PD patients in the UK and subsequent costs to the NHS, social services and the patient according to the time spent per waking day in OFF state. The authors believe that this is the first study to demonstrate the relationship between costs and the amount of time patients spend in OFF state.

Methods

The data collection and analysis comprised two components: (1) data extraction from the Adelphi Disease Specific Programme (DSP), and (2) a categorisation of patients into 12 corresponding health states followed by resource use evaluation and costing per health state. The primary study hypothesis was that increasing time spent in OFF state would result in increasing cost.

Adelphi DSP for PD

This observational, cross-sectional study was based on UK patient-level survey data derived from doctors and patients through the Adelphi Group’s DSP for PD ()Citation18. The study analysis focused on patients with advanced PD, therefore data on patients classified as stages H&Y 3, 4 and 5 were extracted and aggregated from the database.

In the UK, the PD-specific DSP survey is usually conducted annually and takes 4–6 months from the start of fieldwork to initial delivery of results. While PD patients are generally seen by neurologists, in the UK a proportion of the physician interviews were undertaken with geriatricians to reflect how the disease is treated across all levels. The data used for this analysis came from the UK study, fielded between March and July 2008. The sample of physicians included in the DSP survey was selected from a wide geographical spread across the country.

The study analysis included data across the following parameters:

Hospitalisations in the last 12 months, including frequency and reason and duration of last hospitalisation

Consultations with GPs, hospital consultants and PD nurses per year

Tests conducted including CT scan, MRI and single photon emission CT (SPECT)

Living circumstances categorised into home, residential care/sheltered housing and nursing home

Professional caregivers, type and total number of hours per patient per week

Non-professional caregivers (informal care provided by family and friends), number of hours per patient per week

Respite care in the last 12 months, including frequency and duration of the last respite period

Health-state categorisation, resource use and costing

Patients were categorised into one of 12 potential states based on the proportion of time spent in OFF state per waking hours ((0–25% time in OFF = OFF I, 26–50% = OFF II, 51–75% = OFF III, 76–100% = OFF IV), and their H&Y stage (stages 3, 4 or 5). Patient-level resource data were collated for each state and combined with standard unit costs in order to estimate mean state costs.

This analysis took a UK National Health Service (NHS) and Personal Social Services (PSS) perspective and therefore included direct medical costs (NHS) and direct non-medical costs (PSS). Indirect costs were limited to consideration of the costs associated with informal care so a true societal perspective was not analysed. Costs related to PD can be broadly defined as direct medical costs such as hospitalisation and health professional visit costs, direct non-medical costs including professional care costs and indirect costs such as informal care provided by patients’ families, productivity losses due to early retirement and sick-leave. Direct medical costs relating to hospitalisation were analysed, as were visits to medical professionals (consultant, GP and PD nurse) and tests conducted; direct non-medical costs including the costs of professional care (nursing home, residential home or sheltered housing, and professional carers that visited the home); and indirect costs limited to the cost of informal care provided by relatives and friends (). Direct medical costs associated with pharmaceuticals including all PD medications, direct non-medical costs associated with transportation to visits, and indirect costs of sick-leave or retirement due to PD were not included in the study analysis.

Table 1. Costs associated with the care of PD patients.

For every patient in the sample each individual resource use item was extracted from the DSP, and costed to provide a 12-month cost per patient. Patients were then stratified according to their designated OFF/H&Y state to provide a total cost per state. A tabulated overview of mean resource use per health state per year is given in . Each resource item was costed using standard costing references. Unit costs for hospitalisation, respite care and tests were taken from the NHS Reference Costs for Trusts and Primary Care Trusts (PCT) Combined for 2007–2008Citation19. Costs for hospitalisations were calculated as episodes according to the Healthcare Resource Group (HRG) in the Reference Costs for each reason provided in the DSP data. Where relevant, average HRG costs of stay were used to cover the range of code options for each diagnosis.

Table 2. Mean annual resource use per health state.

Where there was more than one reason for the last hospitalisation per patient, the costlier reason was selected. For patients who were hospitalised more than once in the past year, only the reason for last hospitalisation was reported. In such cases, the average of last hospitalisation costs for all 302 patients was used as the cost for all prior-to-last hospitalisations. This method of estimation was also applied to respite care costs.

The unit costs of consultations, professional caregivers and institutional home costs were taken from the Unit Costs for Health and Social Care 2008Citation20. Total professional caregiver costs were estimated in the following manner: if patients were living in an institutional home, i.e. a nursing or residential home or sheltered housing, then the bulk cost per week for this type of home was used as this would cover nursing and auxiliary staff costs. If the patient did not live in an institutional home, then the cost of the professional caregiver was the cost of a home carer multiplied by the total number of hours per week for that patient. The dataset provided details of all types of professional carers including district nurse, social worker and community psychiatric nurse as well as a home care worker, but provided only the total number of hours of care per week and did not distinguish the number of hours according to type. Taking a conservative approach, all professional carers were costed at the hourly rate applied to a local authority home care worker, which is the lowest cost category of professional carers.

presents a summary of the unit costs used to calculate the resource use for the health states.

Table 3. Unit costs for health state resource use.

Results

Data from the Adelphi DSP was aggregated and analysed to present results on patient demographics, resource use and mean costs per health state.

Patient demographics

A total of 60 physicians were recruited for the study (20 geriatricians and 40 neurologists). Data on 655 PD patients was obtained from clinicians. In all, 302 patients matched the study criterion of H&Y stage 3, 4 or 5 and were analysed for their resource use according to their health state. The mean patient age was 71.7 years and 61.3% were male. The majority of patients (68%) in the dataset were found to have a H&Y score of 3 or 4 and reported 0–25% of their time in an OFF state (=OFF I). Only limited data were available for patients in very advanced stages of PD; no patient provided data for OFF IV/H&Y3, and only one patient was in state OFF IV/H&Y4.

Resource use

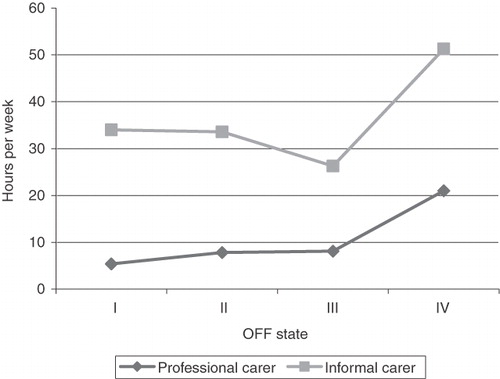

For direct medical resources, 39% of patients were hospitalised, on average 1.6 times per year, with an average length of stay (ALOS) of 16.1 days. Patients attended on average 2.86 consultant visits, 3.52 GP visits and 3.00 PD nurses visits per year. Tests conducted were also included but comprised only a small component of resource use with a mean of 0.29, 0.37 and 0.06 tests per patient (MRI, CAT and SPECT, respectively). In terms of direct non-medical costs, for respite care, 13% of patients were admitted on average 2.7 times per year for an ALOS of 10.5 days. A total of 16% of patients lived in nursing homes (increasing from 10% in OFF I to 50% in OFF IV); 6% lived in residential care or sheltered housing and 78% lived at home. Those who lived at home received on average 6.4 hours professional care and 34.04 hours informal care per week (). Disease progression was associated with increased carer hours, from 5.4 professional carer hours per week for OFF I to 21.00 hours per week for OFF IV; likewise for informal care the number of hours per week rose from 34.00 to 51.25 for OFF states I and IV, respectively.

Figure 2. Mean number of carer hours per week. OFF states III and IV have a limited sample size (n = 11, 8, respectively).

Approximately half of all 19 patients that spent more than 50% of their time in OFF lived in nursing homes (45% of patients in OFF III and 50% in OFF IV). By OFF state IV, when patients suffer from immobility more than 75% of their waking time (n = 10), the results indicate that patients tend to require constant care, either in their own homes or in the nursing home environment.

Costs

The present study found that the relationship between increasing OFF and cost was significant. The average cost per patient per 12 months for each health state is presented in (). Overall, the total cost per patient per annum was £28,700 with £1,881 attributed to direct medical costs, £13,364 to direct non-medical costs and £12,454 to indirect informal care costs.

Table 4. Mean annual costs per health state.

The cost of care, calculated as direct non-medical and indirect costs was the most costly component, accounting for more than 85% of the total costs at all stages. Overall, the direct non-medical costs of professional care accounted for 50% of all costs, indirect informal care 43%, while only 7% of costs were attributed to direct medical costs. Within the direct medical costs, hospitalisation was the most significant cost (£1,378) followed by health professional visits (£385) and tests (£117). visualises the split between the different main cost types assessed.

Despite the low patient numbers in the very severe health states, the results demonstrate that both increasing time spent in OFF and increasing H&Y stage are associated with higher costs, for both the direct costs associated with medical services and professional care. Between OFF I and OFF IV, there is an increase by a factor of 2.4 in mean total costs, from £25,630 to £62,147 per annum; direct medical costs increase from £1,361 to £6,084 while direct non-medical costs increase from £11,356 to £40,246, nearly a four-fold increase. The cost of indirect informal care does not follow the same increasing pattern, fluctuating between a low of £8,838 in OFF III up to £15,817 in OFF IV ().

Statistical tests (standard deviation and 95% confidence interval) show a certain variation amongst patients in each group. However, the overall trend of increasing costs with more time spent in OFF is not hampered by these findings.

Discussion

The study analysis found a significant relationship between cost and time spent in OFF state; costs of both medical services and patient care increased with increasing disease severity, with a specific relationship shown between the time spent in OFF and increasing costs. Total annual costs rose from £25,630 when patients spend less than a quarter of their time in OFF to £62,147 for patients who spend more than 75% in OFF. Direct medical costs were low in relation to the costs of care, the bulk of the costs attributed to professional care ranging from 35% to 77% across all OFF states. In OFF state IV, 90% of all costs are due to care, of which 65% are for professional care costs. In the present study, it was found that patients are increasingly institutionalised as OFF time increases, with nursing home care rising from 10% of patients in OFF I to 50% in OFF IV. It should however be noted that these results need to be interpreted in the context of the limited sample sizes for higher OFF states. Also, co-morbidities such as behavioural disorders or dementia could have been additional reasons for costs increase with disease progression. However, their specific contribution to the observed cost increase has not been studied here.

The study cost breakdown demonstrating that direct medical care accounts for only 7% of costs whilst the remaining 93% is split between professional care (50%) and informal care (43%) differs from other reported UK studies, where greater proportions of costs are attributed to the NHS. However it should be noted that the present analysis did not take into count the cost of PD medications; FindleyCitation5 reported that the NHS accounted for 38% of the direct costs of PD patients in the UK, while 35% of costs were social services costs, and 27% was private expenditure borne by the patient.

PD is also associated with substantial hidden costs; the cost of informal unpaid care provided by family and friends has been demonstrated to be by far the greatest component of societal and family burdenCitation21. In a community-based UK study, McCroneCitation22 reported that direct healthcare costs accounted for 15% of costs, direct non-medical costs associated with social care for 5% and 80% of costs were due to informal care. The lower proportion of costs associated with social care was considered by the authors to be most likely an underestimate of the true cost of social care due to the community-based nature of the study population which lacked representation of severe PD cases. The magnitude of these indirect costs associated with informal care is difficult to asses; our results demonstrate that whilst professional care costs rise steadily with disease progression, informal care costs exhibit a decreasing trend as patients spend more time in OFF (50% of care costs in OFF I versus 25% of care costs in OFF IV). The authors suggest this may be a result of patients requiring more formal, salaried professional care as their disease progresses and they need increasing help, but further evidence is required to support this due to limited patient numbers in the more severe OFF states. In addition, the move from home to residential care has been reported to be associated with a 4.5-fold increase in costs, borne by either social services or by the patient themselves if they chose private careCitation12.

This study reports a detailed analysis of UK-specific resource use data which allows for evaluation of costs by time spent in OFF. The Adelphi DSP is an established method for investigating current treatment practices for a wide range of diseases and complements both methodologically sound RCTs conducted in the research and development setting and observational intervention studies with a wider patient baseCitation18. The DSP effectively captures the attitudes and expectations of patients’ and clinicians’ behaviour and patient management at a point in time using robust and accurate data collection and analysis techniques. This information can be used to identify real-world practices using data from the relevant presenting populations and therefore external validity is high. Data are collected from routine clinical settings with no pre-determined hypothesis which means the outcome measures are not constrained by objective measurements. The methodology employed to collect behavioural and attitudinal information uses procedures to minimise bias which are at least as robust as those used in RCT and observational studies.

However, limitations do apply; patients are not randomly selected but identified on a consecutive basis; identification of patients is based upon the clinician’s diagnosis rather than a formalised diagnostic checklist. Also, being cross-sectional, the DSP cannot demonstrate cause and effect owing to the need for statistical control of confounding factors. For the purposes of the present study analysis, the DSP is limited in that there is very little or no data to directly inform some of the severe health states of the analysis. This is a reflection of the low patient numbers in the more advanced disease stages (OFF IV/H&Y 3 and OFF IV/H&Y 4), as well as difficulties in gaining access to these patients. This is mirrored in the statistical findings such as overlapping confidence intervals shown in . Consequently, the robustness of some conclusions drawn from the results may be subject to scrutiny and further research is needed to substantiate the study results. The present study was also limited since the DSP was not designed with the aim of estimating economic disease burden. Data collection was undertaken from a clinical rather than economic perspective and therefore several data gaps were present. Where information gaps were present, such as data on previous hospitalisations, or hours per type of professional carers, a conservative approach to costing was taken (use of lowest costs applicable per category). As direct medical costs associated with pharmaceuticals (including all PD medications), direct non-medical costs for transportation to visits, and indirect costs due to PD-caused sick-leave or retirement were not included in the study analysis, it is likely that the true costs may be underestimated.

Both disease severity and quality of life (QoL) worsen with time; PD severely impacts the QoL for both the patient and their caregiverCitation2,Citation8,Citation23–25. Patients spend increasingly more time in OFF and require increasing assistance, the disease thus also progressively impacting on their carer causing considerable caregiver burdenCitation21,Citation26–28. Patient deterioration leads to more clinician consultations, more hospitalisations and more day-to-day care, either in their own home or in a nursing home which is associated with considerable costs to the NHS, patients and society. Managing the needs of patients who suffer from degenerative progressive diseases such as PD will be a considerable challenge in the years to come; an ageing population points towards an increasing prevalence of these diseases and changing family structures may well reduce the current inclination towards extended family support. The healthcare system and society will be placed under mounting pressure to solve the problems associated with an increasing demand for care. These factors indicate an unmet need for innovative treatments in advanced PD to slow down disease progression, stabilise the disease or improve disease symptoms. Such treatments will aid patients and their families whilst at the same time reduce costs to the NHS, PSS and society.

Conclusion

There are considerable unmet needs in the treatment of PD; the progressive nature of the disease causes increasing disability and reliance on others for care, in particular in the later stages where symptoms become difficult to control. Patients spend more time in OFF state and require increasing assistance to manage their daily life. The present study analysis has established a relationship between time spent in OFF and the cost of PD, demonstrating that in advanced disease the single most important measured cost component is the cost of professional and informal care.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was funded by Abbott Healthcare Products Ltd., manufacturer of Duodopa. IMS Health conducted the study by order and on account of Abbott Healthcare Products Ltd.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

A.B. is employed by Abbott Products Operations AG, Switzerland. M.S. is employed by Abbott Healthcare Products Ltd, UK.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the contribution of Adelphi Group for providing the data and to James Jackson (project manager, Adelphi Group) for his expertise with the database.

This paper was presented as a poster at the World Parkinson’s Congress in Glasgow in September 2010.

References

- Dodel RC, Eggert KM, Singer MS, et al. Costs of drug treatment in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 1998;13:249-254

- Chrischilles EA, Rubenstein LM, Voelker MD, et al. The health burdens of Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 1998;13:406-413

- Cubo E, Alvarez E, Morant C, et al. Burden of disease related to Parkinson's disease in Spain in the year 2000. Mov Disord 2005;20:1481-1487

- Dodel R, Reese JP, Balzer M, et al. The Economic Burden of Parkinson's Disease. European Neurological Review 2008;3:11-14

- Findley LJ. The economic impact of Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2007;13 Suppl:S8-S12. Epub@2007 Aug 16.:S8-12

- Guttman M, Slaughter PM, Theriault ME, et al. Burden of parkinsonism: a population-based study. Mov Disord 2003;18:313-319

- Huse DM, Schulman K, Orsini L, et al. Burden of illness in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 2005;20:1449-1454

- Keranen T, Kaakkola S, Sotaniemi K, et al. Economic burden and quality of life impairment increase with severity of PD. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2003;9:163-168

- LePen C, Wait S, Moutard-Martin F, et al. Cost of illness and disease severity in a cohort of French patients with Parkinson's disease. Pharmacoeconomics 1999;16:59-69

- Noyes K, Liu H, Li Y, et al. Economic burden associated with Parkinson's disease on elderly Medicare beneficiaries. Mov Disord 2006;21:362-372

- Andlin-Sobocki P, Jonsson B, Wittchen HU, et al. Cost of disorders of the brain in Europe. Eur J Neurol 2005;12 Suppl:1-27: 1-27

- Findley L, Aujla M, Bain PG, et al. Direct economic impact of Parkinson's disease: a research survey in the United Kingdom. Mov Disord 2003;18:1139-1145

- Dodel RC, Singer M, Kohne-Volland R, et al. The economic impact of Parkinson's disease. An estimation based on a 3-month prospective analysis. Pharmacoeconomics 1998;14:299-312

- Hagell P, Nordling S, Reimer J, et al. Resource use and costs in a Swedish cohort of patients with Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 2002;17:1213-1220

- Pechevis M, Clarke CE, Vieregge P, et al. Effects of dyskinesias in Parkinson's disease on quality of life and health-related costs: a prospective European study. Eur J Neurol 2005;12:956-963

- Dewey RB, Jr. Management of motor complications in Parkinson's disease. Neurology 2004;62:S3-7

- Palmer CS, Schmier JK, Snyder E, et al. Patient preferences and utilities for 'off-time' outcomes in the treatment of Parkinson's disease. Qual Life Res 2000;9:819-827

- Anderson P, Benford M, Harris N, et al. Real-world physician and patient behaviour across countries: Disease-Specific Programmes - a means to understand. Curr Med Res Opin 2008;24:3063-3072

- NHS Reference Costs 2007-2008. NHS Trust and PCT Combined Reference Cost Schedule. Appendix NSRC04. Department of Health; London: http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_098945; 2009

- Curtis L. Unit Costs of Health and Social Care. Personal Social Services Research Unit, University of Kent: http://www.pssru.ac.uk/uc/uc2008contents.htm.; 2008

- Whetten-Goldstein K, Sloan F, Kulas E, et al. The burden of Parkinson's disease on society, family, and the individual. J Am Geriatr Soc 1997;45:844-849

- McCrone P, Allcock LM, Burn DJ. Predicting the cost of Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 2007;22:804-812

- Global Parkinson's Disease Survey Steering Committee. Factors impacting on quality of life in Parkinson's disease: results from an international survey. Global Parkinson's Disease Survey Steering Committee. Mov Disord 2002;17:60-7

- Martinez-Martin P, ito-Leon J, Alonso F, et al. Quality of life of caregivers in Parkinson's disease. Qual Life Res 2005;14:436-72

- Schrag A, Jahanshahi M, Quinn N. How does Parkinson's disease affect quality of life? A comparison with quality of life in the general population. Mov Disord 2000;15:1112-18

- Carter JH, Stewart BJ, Archbold PG, et al. Living with a person who has Parkinson's disease: the spouse's perspective by stage of disease. Mov Disord 1998;13:20-28

- Martinez-Martin P, Forjaz MJ, Frades-Payo B, et al. Caregiver burden in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 2007;22:924-931

- Martinez-Martin P, Arroyo S, Rojo-Abuin JM, et al. Burden, perceived health status, and mood among caregivers of Parkinson's disease patients. Mov Disord 2008;23:1673-1680

- The Office of National Statistics. Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings; 2008 Nov 14, 2008