Abstract

Objective:

To perform an economic evaluation of a specific brand of partially hydrolyzed infant formula (PHF-W) in the prevention of atopic dermatitis (AD) among Australian infants.

Methods:

A cost-effectiveness analysis was undertaken from the perspectives of the Department of Health and Aging (DHA), of the family of the affected subject and of society as a whole in Australia, based on a decision-analytic model following a hypothetical representative cohort of Australian newborns who are not exclusively breastfed and who have a familial history of allergic disease (i.e., are deemed ‘at risk’). Costs, consequences, and incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICER) were calculated for PHF-W vs standard cow’s milk based infant formula (SF), and, in a secondary analysis, vs extensively hydrolyzed infant formula (EHF-Whey), when the latter was used for the prevention of AD.

Results:

From a representative starting cohort of 87,724 ‘at risk’ newborns in Australia in 2009, the expected ICERs for PHF-W vs SF were AU$496 from the perspective of the DHA and savings of AUD1739 and AU$1243 from the family and societal perspectives, respectively. When compared to EHF-Whey, PHF-W was associated with savings for the cohort of AU$5,183,474 and AU$6,736,513 from the DHA and societal perspectives.

Limitations:

The generalizability and transferability of results to other settings, populations, or brands of infant formula should be made with caution. Whenever possible, a conservative approach directing bias against PHF-W rather than its comparators was applied in the base case analysis. Assumptions were verified in one-way and probabilistic sensitivity analyses, which confirmed the robustness of the model.

Conclusions:

PHF-W appears to be cost-effective when compared to SF from the DHA perspective, dominant over SF from the other perspectives, and dominant over EHF-Whey from all perspectives, in the prevention of AD in ‘at risk’ infants not exclusively breastfed, in Australia.

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD), also known as eczema or IgE-associated eczema, is an inflammatory, non-contagious, and pruritic skin disorder which has its onset during the first 6 months of lifeCitation1. The International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (covering 66 centers in 37 countries) reported national prevalence rates of ‘ever having had AD’ ranging between 1.2–38.6% for children aged 6–7 years, with a rate of 32.3% for Australia in 2002, a rate which had increased by 43% over 10 yearsCitation2. The development of atopic disease depends on an interaction between genetic factors, environmental factors (including early life microbial exposures), dietary factors, and othersCitation3.

The World Health Organization and Australian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy (ASCIA) recommend exclusive breastfeeding for the first six or four to six months of life, respectivelyCitation4–6. The ASCIA and other scientific bodies recommend that feeding be introduced when infants are four to six months of ageCitation4,Citation7–9. When the infant cannot be breastfed, ASCIA and various international guidelines for prevention of allergic disease recommend that ‘at risk’ infants be assigned hydrolyzed infant formula rather than standard cow’s milk based infant formulas (SF)Citation4,Citation7,Citation10–13.

In Australia, whey-based extensively hydrolyzed infant formulas (EHF) are only available for treatment of established cow’s milk and/or soy allergy and are not recommended for disease prevention. In contrast, partially hydrolyzed formula can be recommended for the purposes of prevention of allergic disease. Partially hydrolyzed formula is thought to have similar hypoallergenic properties to EHF but is associated with lower rates of discontinuation due to a host of factors such as better taste, better texture and less bitternessCitation14–16. So far, only one specific brand of 100% whey-based partially hydrolyzed formula, NAN HA 1 Gold®, manufactured by Nestlé S.A, Switzerland (PHF-W), has been shown in randomized trials and meta-analyses to be effective in the prevention of AD when compared to SFCitation15–19. Indeed, the relative risk (RR) of developing AD at 12 months of age or less, after having consumed PHF-W rather than SF, was reported as 0.68 (95% confidence interval of 0.48–0.98) in a meta-analysis by Szajewska and HorvathCitation18 and as 0.45 (0.30–0.70) in a meta-analysis of ‘methodologically superior’ studies published by Alexander and CabanaCitation19. A third type of infant formula, amino acid-based formulas (AAF), are available for allergy treatment but at a much higher cost.

Treatment of AD accounts for a significant amount of health services financial resources and clinical time as well as placing a quality-of-life burden on the child, family, and societyCitation20. Two studies reported on the economic evidence pertaining to the treatment of AD in AustraliaCitation21,Citation22. KempCitation21 estimated that the societal costs per child per year for treatment ranged from AU$1142 for a child with mild AD to AU$6099 for a child with severe AD; overall yearly costs for treatment was conservatively estimated at AU$ 317 M. According to Su et al.Citation22, the total costs per case were estimated to the family at AU$480, 1712, and 2545 for mild, moderate, and severe AD, respectively. Furthermore, the authors postulated that families of children with moderate or severe AD had a significantly higher impact than families of diabetic childrenCitation22.

The cost-effectiveness of PHF-W in the prevention of AD for ‘at risk’ children has been established in FranceCitation23, DenmarkCitation24, and other countriesCitation25, but no such economic evaluation has been published for an Australian setting. The present pharmacoeconomic analysis determines the costs, consequences, and cost-effectiveness of PHF-W vs SF in the prevention of AD in ‘at risk’ children in Australia.

Methods

Product, disease, population, and time horizon

The product of interest was PHF-W and the main comparator in the base case analysis was SF; the use of EHF for prevention was explored in sensitivity analyses (SAs). The disease of interest was AD, which is commonly the first allergic disease manifestation observed in infants and also the most prevalent allergic condition in the first years of life. The population of interest were healthy ‘at risk’ subjects who were not exclusively breastfed, ranging from newborns to 3-year olds, as current international guidelines would recommend the use of hydrolyzed formulas for prevention of allergic disease in ‘at risk’ infants and toddlers. ‘At risk’ children were defined as having at least one parent or sibling with a reported history of allergies. The period of breast milk or infant formula consumption was assumed to cover the first 6 months of life. The base case analysis was undertaken for a time horizon of 12 months, covering the period by which most cases of AD would have occurred while extending beyond the period of milk consumption.

Perspective

The present study was undertaken by adopting three perspectives: the perspective of the Australian public healthcare system represented by the Department of Health and Aging (DHA), the perspective of the family of the subject, and the perspective of society as a whole which took into account both the DHA and family perspectives.

Type of economic evaluation

A cost-effectiveness approach was chosen as it offered the best means to measuring the costs and outcomes that are most relevant to both the children and their parents as well as the DHA. A cost-utility approach was not adopted as no direct measure of utility associated to AD was reported in the available literature, while the age of the population of interest signified that elicitation of utility would be impractical without the input of their parents or other proxies.

Clinical outcomes

The incidence rate of AD with SF and the RR of developing AD symptoms with PHF-W vs SF were reported in a meta-analysis by Szajewska and HorvathCitation18 (the only meta-analysis solely focusing on the formula of interest in the present study) and adapted for the present model into outcomes at 6, 12, 18, 24, 30, and 36 months by applying an approach described by Iskedjian et al.Citation26.

This analysis explored the prevention of AD rather than its occurrence. As such, the final clinical outcome of the base case analysis was the attributable risk for PHF-W vs SF, that is, the number of AD cases expected to be avoided (prevented) when consuming PHF-W rather than SF.

Economic outcomes and incremental ratios

The intermediate economic outcomes were the aggregated costs associated with PHF-W and SF from each perspective (i.e., DHA, family, and societal perspectives), while the final economic outcome was the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) expressed in terms of an expected incremental cost per avoided case of AD. The simplified mathematical formulation of the ICER is presented below:

The application of a negative coefficient is required as this is an analysis of preventive outcomes.

Expert panel

An expert panel consisting of six expert pediatric clinicians (one neonatologist, one expert in dermatology, three experts in immunology and allergy, and one expert in gastroenterology and allergy) was convened in order to define the current medical practices and resources used in the management of AD in Australia. The input obtained from the expert clinicians was synthesized into the model, after resolving any point of contention.

Summary of model structure

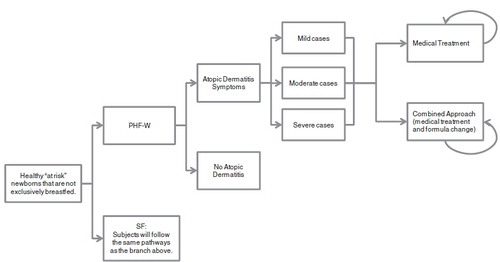

As presented in , a spreadsheet-based (MS Excel® 2003) decision-analytic economic model, based on a series of 6-month cycles, was developed in order to depict the medical practices associated with the treatment of AD in Australia.

Figure 1. Illustration of decision tree model depicting the treatment patterns of atopic dermatitis in Australia in a population ranging from newborns to 3-year olds. PHF-W, Nestlé brand of 100% whey-based partially hydrolyzed formula; SF, Standard cow’s milk formula.

The initial cohort entering the model represented the target population of this study and was defined by the following mathematical formulation:

The number of infants born in Australia in 2009 was obtained from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS)Citation27. The Australian Institute of Family StudiesCitation28 reported the rate of exclusive breastfeeding for the first 12 months of age. The mean rate of exclusive breastfeeding at 2, 4, and 6 months was applied in determining the initial cohort entering the present model. Although an approximation of the rate of newborns who were ‘at risk’ of developing AD could be made for Europe (33%)Citation14,Citation29,Citation30, a higher rate of 50% was used in the base case analysis at the behest of the expert panel.

Subjects were assigned to one of two arms receiving either PHF-W or SF and were then divided into two groups: those subjects with AD and those subjects without AD. For those subjects who were affected by AD, a disease severity was assigned as per the expert panel.

As per expert opinion, discontinuation due to taste and/or texture was only taken into account for PHF-W and EHF-Whey, 3 days after the initial allocation of infant formula. In the case of discontinuation, it was assumed that subjects consumed a different brand of the same type of infant formula of equal cost to the brand that had initially been used.

Subjects with AD were presented with an age-specific plan to manage their AD, consisting of a medical treatment approach or an approach combining the medical treatment approach with one or more changes of infant formula. After the first 6 months, subjects with AD symptoms could only be treated with the medical treatment approach. Each approach was divided into up to four lines of treatment, characterized by a specific combination of therapies and/or formula as well as specific types of medical visits. The expert panel provided expected average response rates (defined as an improvement of AD symptoms) for each line of treatment.

Although AD does not affect mortality rates, the reality of a cohort of newborns aging to 3 years of age was modeled by taken into account the baseline mortality rates for infants born in Australia published by the ABS from 2007–2009Citation31.

Please refer to and for a detailed breakdown of the epidemiological and clinical parameters applied in the present model.

Table 1. Epidemiological and clinical parameters applied in the model.

Table 2. Economic parameters applied in the base case analysis.

Resource utilization and costs

Currently in Australia, the DHA does not cover the costs of SF or infant formulas used in prevention. In the present model, it was assumed that both SF and infant formulas used in prevention would be covered by the DHA at the same rate. Furthermore, should there be coverage for the cost of PHF-W, it would be ∼75% covered by the DHA and 25% by the family, when taking into account coverage under concession and co-pays in various segments of the target population.

The price of each infant formula was obtained from a survey of pharmacies and large-scale retail outlets in Australia. The daily intake of infant formula was determined based on the instructions for the preparation of PHF-W (these instructions were similar for the other infant formulas) and by factoring in the rate of ever-breastfed Infants (i.e., infants receiving full or complimentary breast milk) derived from a report by the Australian Institute of Family StudiesCitation28 and calculated in a manner described in a previous publicationCitation25.

According to the expert panel, all first-line medical visits were standard consultations with a general practitioner. Subsequently, depending on the severity of the disease and the response to the lines of treatment, subjects were to visit a pediatrician or a dermatologist. The exact breakdown of these visits is presented in , along with the costs of medical consultations, as obtained from the Medicare Benefits Schedule Book published by the Australian Government, Department of Health and Aging (AGDHA)Citation32. Bulk billing for physician consultation fees was not taken into account.

According to the expert panel, subjects could be hospitalized for up to 4.5 days, depending on the severity of their disease. The cost of hospitalization was derived for subjects with mild, moderate, and severe AD, from a survey of a local hospital in Melbourne, Australia (based on personal communications with Dr Su, Royal Children’s Hospital, Melbourne, Australia). These costs and utilization of these resources are presented in .

The medications and therapies used by affected subjects consisted of a combination of emollients, wet dressings, naturopathic treatments, and prescription medications (including infant formulas used as treatment, not in prevention). The breakdown and price of these resources is presented in . The cost of emollients was obtained from an online directoryCitation33, whereas the cost of wet dressings and naturopathic treatment were derived, with the input of the expert panel, from a costing analysis published by Su et al.Citation22 in 1997. These costs (i.e., costs of emollients, wet dressing, and naturopathic treatment) were entirely assigned to the family, as is currently the case in Australia. The cost of prescription medications was obtained from the AGDHA’s Pharmaceutical Benefits SchemeCitation34. In Australia, the reimbursement of prescription medication costs is specific to two patient demographics: the general public or concession patients. For the general public, the cost of prescription medication includes the cost of the medication itself, mark-up, and dispensing fees as well as, in some instances, Pharmaceutical Benefit Scheme Safety Net recording fees and allowable extra feesCitation34,Citation35. The family of the patient is responsible for all prescription medication costs under AU$35.40, with the DHA covering any costs over that thresholdCitation34. This is also true of families with concession cards, except that the maximum amount payable by the family per prescription is AU$5.80Citation34. Barozzi et al.Citation36 reported that 24% of the Australian population were included in the concession scheme. However, given that an important proportion of this population is elderlyCitation37, it was assumed, in the present analysis, that the proportion of patients on concession, rather than in the general public, was 20%.

According to the expert panel, subjects with mild AD were not administered any diagnostic tests, while those with moderate or severe AD would be administered the specific IgE test, the prick test, the patch test, and/or skin or nasal swabs. The costs and reimbursement rates for these laboratory tests were obtained from AGDHA’s Medicare Benefits Schedule BookCitation32.

From the family and societal perspectives, indirect costs due to leisure time loss and/or productivity loss were included in the model. These indirect costs were determined by taking into account the population rate of participation in the workforce in Australia in 2011Citation38, as well as the average gross hourly wage and daily hours of work for each economic activity in AustraliaCitation39,Citation40. As per expert opinion, it was also assumed that 4 hours were required for physician visits and for laboratory testing (including travel to and from the medical office), that 2 full days were needed for childcare after the initial medical visit, and 10 minutes were required for each application of emollients or topical prescription medications.

The cost of travel to and from the physician’s office, for an assumed distance of 10 km, was established by using an average of the cost of public transportation (bus and metro), taxi, and operating a personal car (using the per-kilometer rate for the taxis excluding the flag fall as well as the booking and time fees) in Melbourne and SydneyCitation41–44.

Discounting

All costs beyond 1 year were discounted at 5%, but outcomes were defined with or without such discounting as per the national guidelines defined by the AGDHACitation45.

Comparisons to EHF-whey

Although not indicated for prevention, some physicians choose to recommend EHF-Whey in the prevention of AD symptoms. This scenario was explored in a secondary analysis where, based on the reported non-significant difference between the RR of PHF-W vs EHF-WheyCitation18, the same efficacy was applied to both formula preparations, amounting to a cost-minimization exercise based on the difference in the acquisition cost of the formulas. In this secondary analysis, the same pattern was applied for the combined management of AD with PHF-W, while subjects consuming EHF-Whey were immediately assigned AAF.

Variability and uncertainty

One-way SAs were carried out to test the robustness of the model by varying numerous parameters such as time horizon, reimbursement rates, resource utilization, as well as direct and indirect costs. Furthermore, using a set of 10,000 Monte Carlo simulations, probabilistic SAs were performed by simultaneously varying multiple parameter values according to pre-defined ranges and types of distribution (presented in ).

Table 3. Parameter estimates and distributions for variables tested in the Monte Carlo sensitivity analysis.

Results

Base-case analysis

For a birth cohort of 295,700 newborns in Australia in 2009, the starting cohort entering the model had 87,724 ‘at risk’ newborns, assumed to be taking either PHF-W or SF.

presents the results of the base case analysis from the three perspectives (DHA, family, and society) when comparing subjects who consumed PHF-W to those who consumed SF. From the DHA, the highest cost was attributable to formula, while the cost of time lost was the main cost driver from the perspective of the subject’s family. The expected incremental costs per avoided case of AD (i.e., the expected ICERs) were AU$496 from the perspective of the DHA and savings of AU$1739 and AU$1243 from the family and societal perspectives, respectively.

Table 4. Base case results presented from the perspective of the Department of Health and Aging, of the family of the subject, and of society as a whole.

PHF-W vs EHF analysis

PHF-W was dominant over EHF-Whey in the scenario where the latter was used in the prevention of AD symptoms given the assumption that both formulae are equally effective in the prevention of AD. The savings for the cohort with the use of PHF-W over EHF-Whey would amount to AU$6,736,513 from the societal perspective, including savings of AU$5,183,474 from the perspective of the DHA.

One-way sensitivity analyses

Table 5. Results of the one-way sensitivity analyses presented from the perspective of the Ministry of Health, of the family of the subject, and of society as a whole.

In the one-way SA where PHF-W was introduced into a new program where there was no formula previously covered for prevention of AD under the DHA (i.e., SF was not covered), the ICER associated with the societal perspective remained unchanged (savings of AU$1243) as cost of formula was shifted from the DHA to the family perspective. Furthermore, from the DHA perspective, the ICERs were higher than the base case when the DHA paid 100%, 75%, or 25% of PHF-W costs AU$7803, AU$5797, and AU$1784, respectively), but similar to the base case when the DHA covered the difference of PHF-W and SF costs (AU$674) and when the DHA paid 10% of PHF-W costs (AU$580). A cost-neutral ICER was observed when the DHA paid for 2.77% of PHF-W costs.

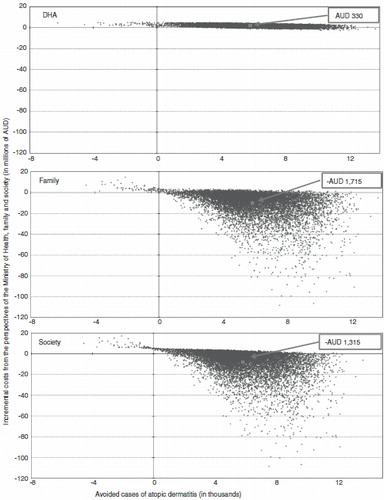

Probabilistic sensitivity analyses

Presented in are the results of the probabilistic SAs from all three analytical perspectives. The expected average Monte Carlo ICERs were AU$330 and savings of AU$1715 and AU$1385 from the DHA, family, and societal perspectives, respectively, with a 91.7%, 27.3%, and 37.8% probability for Monte Carlo results to fall below a line linking the base case ICERs to the origin.

Figure 2. Results of the Monte Carlo simulations from the DHA, family and societal perspectives. The ICERs presented in boxes above were obtained by dividing the average incremental costs by the average avoided cases of AD which were generated from the 10,000 Monte Carlo simulations. The base case incremental cost-effectiveness ratios were AU$496, −AU$1739, and −AU$1243 from the DHA, family, and societal perspectives, respectively. By accounting for the incremental costs and outcomes of each simulation, median ICERS of AU$328, −AU$1146, and −AU$761 were generated from the DHA, family, and societal perspectives, respectively. Quadrant 1 is associated with potential cost-effectiveness of PHF-W as it displays positive incremental costs and avoided cases (probabilities of 92.6%, 9.6%, and 24.2% from the DHA, family, and societal perspectives). Quadrant 2 represents dominance by SF, as incremental costs for PHF-W vs SF are positive while avoided cases are negative (probabilities of 0.7% from all three perspectives). Quadrant 3 represents the unlikely scenario where incremental costs are negative but so are avoided cases (no probability from any perspective). Quadrant 4 denotes dominance by PHF-W over SF as incremental costs and avoided cases are both negative (probabilities of 6.7%, 89.7%, and 75.1% from the DHA, family, and societal perspectives). DHA, Department of Health and Aging; ICER, Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio.

Discussion

This is the first published study pertaining to the cost-effectiveness of PHF-W in the prevention of AD in ‘at risk’ children in Australia. Based on a series of inputs and assumptions provided and/or verified by a panel of experts in Australia, PHF-W appears to be dominant when compared to SF in the prevention of AD among ‘at risk’ infants who are not exclusively breastfed from the perspectives of the family or society as a whole and dominant from the DHA perspective. This was confirmed in an SA based on another meta-analysis pertaining to infant formula and AD prophylaxisCitation12, indicating that the two most recently-published meta-analyses yielded congruent results. Similar findings have been observed in previously-published analyses undertaken in other settingsCitation23–25.

The main cost drivers were the cost of infant formula from the DHA perspective and the cost of productivity or leisure time lost due to child care from the perspective of the family of the affected child. The present study adopted a conservative approach by limiting the disease of interest to AD, rather than broader allergic manifestations, and by not taking into account other significant outcomes of AD such as pain and suffering, given that they would be difficult to evaluate and monetize in the population of interest.

A secondary analysis exploring a scenario wherein EHF-Whey would be used in prevention yielded important cost savings with PHF-W, hence suggesting that this use of EHF-Whey would be incongruous, especially in view of the greater rates of non-compliance due to taste or texture associated with EHF-Whey.

Limitations

This analysis, based on a predictive model, is based on a certain number of assumptions and may involve a certain amount of bias, as any predictive model would. However, the base case analysis was performed, whenever feasible, by applying a conservative approach which would direct the bias against PHF-W rather than its comparators. Furthermore, the assumptions and inputs of the present model were overseen by a panel of experts wholly familiar with the management of AD in the population of interest in Australia. All assumptions were verified in one-way and probabilistic SAs, which confirmed the robustness of the model.

In the secondary analysis comparing PHF-W to EHF-Whey, it was assumed, as per the findings of a recent meta-analysisCitation18, that both of those infant formulas had the same efficacy. According to the findings of another meta-analysis which reported no significant difference in the preventive efficacy of EHF-Whey vs SFCitation46, the approach adopted in the present secondary analysis may have over-estimated the preventive efficacy of EHF-Whey and, in turn, introduced a bias against PHF-W.

The present analysis was targeted to a specific brand of partially hydrolyzed formula, to a specific population and to a specific setting. As a consequence, the generalizability and transferability of results to another setting, population, or brand of infant formula should be made with caution, especially that the clinical outcomes applied in the present analysis were based on evidence from meta-analyses directed to the specific brand of partially hydrolyzed formula of interest in the present study (PHF-W).

Conclusions

PHF-W appears to be cost-effective when compared to SF for the prevention of AD symptoms in ‘at risk’ infants and very young children who are not exclusively breastfed, when analysed from the perspective of the DHA in Australia, and dominant over SF from the perspectives of the family or of society as a whole. PHF-W also yielded cost savings in comparison to EHF-Whey when the latter was used for the prevention, rather than treatment, of AD.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was funded by Nestlé Nutrition Institute (NNI).

Declaration of financial/other relationships

MI is the president of PharmIdeas, which performed this study under contract with NNI; JS is employed by NNI; JS, SP, MT, PS, RH, and JS have received honoraria for their participation.

The peer reviewers on this manuscript have disclosed that they have no relevant financial relationships.

Notice of Correction

The version of this article published online ahead of print on 19 September 2012 contained an error on the second page. There was an error in the wording of the Introduction which has been corrected for this version.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Peter Fryer, Dr Patrick Detzel, Bechara Farah, Jade Berbari, and Vincent Navarro for their analytical and editorial input.

References

- Spergel J, Paller A. Atopic dermatitis and the atopic march. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2003;112:S118-27

- Asher M, Montefort S, Björkstén B, et al. Worldwide time trends in the prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema in childhood: ISAAC phases one and three repeat multicountry cross-sectional surveys. Lancet 2006;368:733-43

- Renz H, Autenreith I, Brandtzaeg P, et al. Gene-environment interaction in chronic disease: a European Science Foundation forward look J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011;128:S27-S49

- Prescott S, Tang M. The Australasian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy position statement: summary of allergy prevention in children. Med J Aust 2005;182:464-7

- World Health Organization, United Nations Children's Fund. Global strategy for infant and young child feeding. Geneva: NLM Classification; WS 120,2003

- World Health Organization. World Health Organization's recommendations on breasfeeding. http://www.who.int/topics/breastfeeding/en. Accessed September 19, 2012

- Boyce J, Assaa'ad A, Burks A, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of food allergy in the United States: report of the NIAID-Sponsored Expert Panel. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2010;126:S1-S58

- Greer F, Sicherer S, Burks A. Effects of early nutritional interventions on the development of atopic disease in infants and children: the role of maternal dietary restriction, breasfeeding, timing of introduction of complementary foods, and hydrolyzed formulas. Pediatrics 2008;121:183-91

- Høst A, Halken S, Muraro A, et al. Dietary prevention of allergic diseases in infants and small children. Amendment to previous published articles in Pediatric Allergy and Immunology 2004, by an expert group set up by the Section on Pediatrics, European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2008;19:1-4

- Baehler P, Baenziger O, Belli D, et al. Empfehlungen für die Säuglingsernährung 2009. Paediatrica 2009;20:13-15

- Chouraqui J-P, Dupont A, Bocquet A, et al. Alimentation des premiers mois de vie et prevention de l'allergie (Feeding during the first months of life and prevention of allergy). Arch Pédiatr 2008;15:431-42

- Dalmau Serra J, Martorell Aragonés A. Alergia a proteínas de leche de vaca: prevención primaria. Aspectos nutricionales. Anal Pediatr 2008;68:295-300

- Muche-Borowski C, Kopp M, Reese I, et al. Allergieprävention. 2009. Report No.: AWMF Guideline Register 061/16

- Exl B-M. A review of recent developments in the use of moderately hydrolyzed whey formulae in infant nutrition. Nutr Res 2001;21:355-79

- von Berg A, Koletzko S, Filipiak-Pittroff B, et al. The effect of hydrolyzed cow's milk formula for allergy prevention in the first year of life: The German Infant Nutritional Intervention Study, a randomized double-blind trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2003;111:533-40

- von Berg A, Filipiak-Pittroff B, Krämer U, et al. Preventative effect of hydrolyzed formulas persists until age 6 years: long-term results from the German Infant Nutritional Intervention Study (GINI). J Allergy Clin Immunol 2008;121:1442-7

- von Berg A, Koletzko S, Filipiak-Pittroff B, et al. Certian hydrolyzed formulas reduce the incidence of atopic dermatitis but not that of asthma: three-year results of the German Infant Nutritional Intervention Study. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007;119:718-25

- Szajewska H, Horvath A. Meta-analysis of the evidence for a partially hydrolyzed 100% whey formula for the prevention of allergic diseases. Curr Med Res Opin 2010;26:423-37

- Alexander D, Cabana M. Partially hydrolyzed 100% whey protein infant formula and reduced risk of atopic dermatitis: a meta-analysis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2010;50:422-30

- Lewis-Jones S. Quality of life and childhood atopic dermatitis: the misery of living with childhood eczema. Int J Clin Pract 2006;60:984-92

- Kemp A. Atopic eczema: its social and financial costs. J Paediatr Child Health 1999;35:229-31

- Su J, Kemp A, Varigos G, et al. Atopic eczema: its impact on the family and financial cost. Arch Dis Child 1997;76:159-162

- Iskedjian M, Dupont C, Kanny G, et al. Economic evaluation of a 100% whey-based, partially hydrolyzed formula in the prevention of atopic dermatitis among French children. Curr Med Res Opin 2010;26:2607-26

- Iskedjian M, Haschke F, Farah B, et al. Economic evaluation of a 100% whey-based partially hydrolyzed infant formula in the prevention of atopic dermatitis among Danish children. J Med Econ 2011;15(2):394-408

- Iskedjian M, Belli D, Farah B, et al. Economic evaluation of a 100% whey-based partially hydrolyzed infant formula in the prevention of atopic dermatitis among Swiss children. J Med Econ 2011;15(2):378-393

- Iskedjian M, Szajewska H, Spieldenner J, et al. Extension of a meta-analysis of the evidence for a partially hydrolyzed 100%-whey formula in the prevention of atopic dermatitis: brief research report. Curr Med Res Opin 2010;26:2599-606

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Number of Births in Australia in 2009. http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/Products/F57D30403E4EBD9BCA2577CF000DEFBD?opendocument. Accessed January 11, 2012

- Australian Institute of Family Studies. Annual Report 2006--2007 -- Breasfeeding. http://www.aifs.gov.au/growingup/pubs/ar/ar200607/breastfeeding.html. Accessed: January 11, 2012

- Bergmann R, Edenharter G, Bergmann K, et al. Atopic dermatitis in early infancy predicts allergic airway disease at 5 years. Clin Exp Allergy 1998;28:965-70

- Halken S. Allergy Review Series VI: the immunology of fetuses and infants. The lessons of noninterventional and interventional prospective studies on the development of atopic disease during childhood. Allergy 2000;55:793-802

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Deaths in Austrlia, 2009 -- Life Tables (Tables 4.1 and 4.2). http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/Products/381E296AFC292B6CCA2577D60010A095?opendocument. Accessed January 11, 2012

- Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. Medicare Benefits Schedule Book -- Operating from 01 January 2012. http://www.health.gov.au/internet/mbsonline/publishing.nsf/Content/678D016AC77C6767CA2579500078C094/$File/201201-Cat%202.pdf. Accessed January 11, 2012

- Pharmacy Direct. Emollient cost. http://www.pharmacydirect.com.au/product_details.aspx?invpid=018079. Accessed January 11, 2012

- Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS). http://www.pbs.gov.au/pbs/home. Accessed January 11, 2012

- Australian Government -- Medicare Australia. Explanation of Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) Pricing. http://www.medicareaustralia.gov.au/provider/pubs/program/files/2526-explanation-of-pbs-pricing.pdf. Accessed January 11, 2012

- Barozzi N, Sketris I, Cooke C, et al. Comparison of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors use in Australia and Nova Scotia (Canada). Br J Clin Pharmacol 2009;68:106-15

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australia -- 2006 Census of Population and Housing -- Age (Full classification list) by sex -- (Cat. No. 2068.0). http://www.censusdata.abs.gov.au/ABSNavigation/prenav/ViewData?method=Placeof%20Usual%20Residence&subaction=-1&producttype=Census%20Tables&areacode=0&order=1&productlabel=Age%20(full%20classification%20list)%20by%20Sex%20&tabname=Details&action=404&documenttype=Details&collection=Census&textversion=false&breadcrumb=TLPD&period=2006&issue=2006&javascript=true&navmapdisplayed=true&documentproductno=0&. Accessed January 11, 2012

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Labour force in Austrlia. 2011. http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/mf/6202.0. Accessed January 11, 2012

- International Labour Organization. Hours of work per week by economic activity in Australia in 2008 (Table 4A). http://laborsta.ilo.org/. Accessed January 11, 2012

- International Labour Organization. Wages by economic activity in Australia in 2006 (Table 5A). http://laborsta.ilo.org/. Accessed January 11, 2012

- New South Wales Government. Maximum taxi fares and charges for 2011. http://www.transport.nsw.gov.au/content/maximum-taxi-fares-and-charges. Accessed January 11, 2012

- New South Wales Government-Transport Info. All fares (transport info). http://www.131500.com.au/tickets/fares/all-faresmybus. Accessed January 11, 2012

- State Government of Victoria A. Taxi fares in Victoria. http://www.transport.vic.gov.au/taxis/customers/taxi-fares-in-victori.a. Accessed January 11, 2012

- State Government of Victoria A. Myki metro fares 2012. http://www.myki.com.au/Fares/Metro-fares-/2012-Metro-fares. Accessed January 11, 2012

- Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. Guidelines for preparing submissions to the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee (Version 4.3). 2008. http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/content/AECB791C29482920CA25724400188EDB/$File/PBAC4.3.2.pdf. Accessed January 11, 2012

- Osborn DA, Sinn JKH. Formulas containing hydrolysed protein for prevention of allergy and food intolerance in infants. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2006, Issue 4. Art. No.: CD003664. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003664.pub3.

- Briggs A, Clarxton K, Sculpher M. Decision modeling for health economic evaluation. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2008