Abstract

Objective:

To estimate annual biologic response modifier (BRM) cost per treated patient with rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, and/or ankylosing spondylitis receiving etanercept, abatacept, adalimumab, certolizumab, golimumab, infliximab, rituximab, or ustekinumab.

Methods:

This was a cohort study of 69,349 commercially insured individuals in a nationwide claims database with one of these conditions that had a claim for one of these BRMs between January 2008 and December 2010 (the index BRM/index date). Cost per treated patient was calculated as the total BRM acquisition and administration cost to the payer in the first year after the index date (including costs of other BRMs after switching) divided by the number of patients who received the index BRM. Etanercept was selected as the reference for comparisons.

Results:

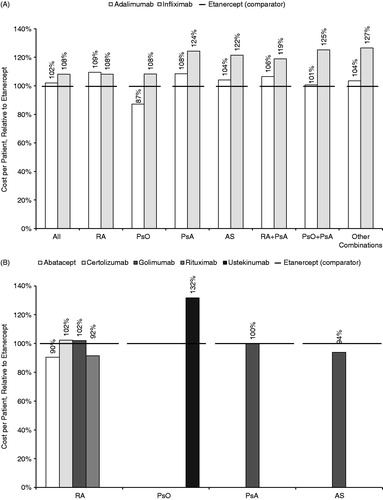

Etanercept was the most commonly used index BRM (n = 32,298; 47%), followed by adalimumab (n = 20,582; 30%), infliximab (n = 11,157; 16%), abatacept (n = 2633; 4%), rituximab (n = 1359; 2%), golimumab (n = 687; <1%), ustekinumab (n = 388; <1%), and certolizumab (n = 245; <1%). Using etanercept as the reference, the cost per treated patient in the first year across all four conditions was 102% for adalimumab and 108% for infliximab. Newer BRMs had costs relative to etanercept that were 90% to 102% for rheumatoid arthritis, 132% for psoriasis, 100% for psoriatic arthritis, and 94% for ankylosing spondylitis.

Limitations:

Potential study limitations were the lack of clinical information (e.g., disease severity, treatment outcomes) or indirect costs, the inability to compare costs of newer BRMs across all four conditions, and much smaller sample sizes for newer BRMs.

Conclusions:

Of the BRMs that are approved for indications within all four conditions studied, etanercept had the lowest cost per treated patient when assessed across all four conditions.

Introduction

The tumor necrosis factor (TNF) blockers etanercept, adalimumab, and infliximab are approved for use in adults with moderate-to-severe rheumatoid arthritis (RA), moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis (PsO) (infliximab for severe only), active psoriatic arthritis (PsA), and active ankylosing spondylitis (AS)Citation1–3. Systematic reviews of available studies have reported that etanercept, adalimumab, and infliximab exhibited similar levels of efficacy and incidences of adverse events in RACitation4,Citation5, PsOCitation6,Citation7, PsACitation8, or ASCitation9. Numerous analyses have used information from claims databases to evaluate the relative costs of etanercept, adalimumab, and infliximabCitation10–21. Most of the analyses were limited to patients with RACitation10–18, which is the most common condition in which TNF blockers are used. A few of the analyses included TNF-blocker costs across multiple conditionsCitation19–21, which allowed for a more complete estimate of the total cost that a payer might incur to include these medications on its formulary.

Several other biologic response modifiers (BRMs) have also become available for use in patients with RA, PsO, PsA, and/or AS. These include the TNF blockers certolizumab (moderate-to-severe RA) and golimumab (moderate-to-severe RA, active PsA, and active AS), and the non-TNF blockers abatacept (moderate-to-severe RA), rituximab (moderate-to-severe RA [after a TNF blocker]), tocilizumab (moderate-to-severe RA after at least one other medication), and ustekinumab (moderate-to-severe PsO). These agents were not included in the previous analyses, and, to date, there are no published analyses comparing the costs of etanercept, adalimumab, or infliximab with those of the newer BRMs in clinical practice. A systematic review of clinical data for both the established TNF blockers and newer BRMs concluded in moderate-to-severe RA there were no significant differences in achieving ACR 50, and there were more withdrawals due to adverse events for both certolizumab and infliximab than for etanercept and rituximabCitation5. However, the report concluded that the level of evidence to support differences between agents was low, and that head-to-head studies are needed to confirm or refute these results before any firm clinical recommendations can be madeCitation5. In the absence of strong evidence to suggest that one BRM is clinically superior to the others, it is reasonable to compare directly the costs of BRMs to the payer.

The objective of this analysis was to use actual drug utilization to estimate treatment patterns and the annual cost per treated patient with a diagnosis of RA, PsO, PsA, or AS (or a combination of these conditions) who received a BRM. The diagnoses were selected to enable the determination of relative costs for each BRM as compared with a single reference. For this analysis, the TNF blocker etanercept was selected as the comparator. Etanercept is approved for indications within each of the conditions studied, has been available for the longest time, and is the most commonly used BRM across all four conditions combinedCitation19,Citation20. Therefore, the four adult indications within which etanercept is approved were included in the analysis.

Patients and methods

Study population

This retrospective US claims analysis used administrative claims data from Truven Health Analytics (formerly Thomson Reuters) analyses of the MarketScan® Commercial Claims and Encounters Database. The database includes fully adjudicated medical and pharmaceutical claims for ∼30 million unique patients annually from 130 health plans across the US, including ∼10 million covered lives per year with a minimum of 18 months of continuous enrollment. The database includes inpatient and outpatient diagnoses (in the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM] format) and procedures (in the CPT-4 and HCPCS formats), and both retail and mail order prescription records. Available data on prescription records include the National Drug Code as well as the quantity of medication dispensed. Additional data elements include demographic variables (age, gender, and geographic region), product type (e.g., health maintenance organization, preferred provider organization), provider specialty, and eligibility dates related to plan enrollment and participation.

The model included adult patients of 18–63 years of age who had at least one claim between January 2008 and December 2010 for etanercept, abatacept, adalimumab, certolizumab, golimumab, infliximab, rituximab, tocilizumab, or ustekinumab. The index claim was set as the first observed claim for a study medication, after at least 180 days of continuous enrollment in the health plan, that met all other inclusion and exclusion criteria. The index date was the date of the index claim. Eligible patients were continuously enrolled in a plan with medical and pharmacy benefits for at least 180 days before (the ‘pre-index’ period) and 360 days after (including) the index date (the ‘post-index’ period). They were also required to have at least one claim with an ICD-9-CM code for RA (714.0x), PsO (696.1), PsA (696.0), or AS (720.0) within 180 days before the index date. During the study period, each of the study medications was approved for indications within at least one of the analyzed conditions. The analysis only included patients who had conditions within which the BRM was approved (e.g., the ustekinumab sample only included PsO because that is the only indication within which it was approved).

Patients were excluded if they had other conditions during their pre-index period within which some of these agents are approved, specifically, juvenile idiopathic arthritis (ICD-9-CM: 714.3x), chronic lymphocytic leukemia (204.1x), Crohn’s disease (555.9), ulcerative colitis (556.x), or non-Hodgkin lymphoma (200.xx or 202.xx). Patients with an index claim for tocilizumab were initially considered, but were removed from the analysis due to the small sample size (n = 12; 0.02%).

Data analysis

All data analysis was descriptive and stratified by index BRM, diagnosis, and new or continuing treatment. Diagnoses included one of seven categories: (1) RA; (2) PsO; (3) PsA; (4) AS; (5) RA plus PsA (without PsO or AS); (6) PsO plus PsA (without RA or AS); and (7) any other combination. Patients with multiple conditions who received a BRM that was approved for an indication within only one of their conditions were assigned to a combination cohort that included the approved condition.

Summary data were calculated for baseline demographics (age and gender), plan type, patient geographic region, prescribing physician specialty for claims within 10 days before the index date, and treatment status (new or continuing). Patients were considered to be new to their index BRM treatment if they had no claim for their index BRM during the 180-day period prior to the index date. Continuing patients were those who had a claim for their index TNF blocker during the 180-day pre-index period.

Expenditures were calculated based on the quantity of each medication used (mg), the cost per mg of each medication, and administration costs. To determine the cost per claim to a health plan, the mean dose (in mg) per claim was calculated. Then, the drug cost for that dose was calculated using Wholesale Administration Cost (WAC) in June 2013; the copayment per claim was deducted, the dispensing fee was added, and the resulting number was then divided by the mean number of mg per claim to calculate the final cost per mg to the health plan. Copayment was 19% for intravenous BRMs (infliximab, abatacept, or rituximab) and $51 for subcutaneous BRMs (all other study medications), based on a 2012 annual national survey of employer health benefitsCitation22. Dispensing fee was $2.50 for each subcutaneous BRM.

Administration costs for etanercept, abatacept, adalimumab, certolizumab, golimumab, infliximab, rituximab, and ustekinumab were based on Medicare fee schedules for subcutaneous injections and intravenous infusionsCitation23. In the modeled scenario, it was estimated that a provider administered the first injection in new patients receiving a self-administered agent (at a cost of $26) and then the patients self-administered subsequent subcutaneous injections for the remaining duration of their treatment. This estimate was used for all subcutaneously administered medications despite the requirement that ustekinumab should only be administered by a healthcare provider, per labelCitation24, based on a lack of injection claims for ustekinumab billed separately from other scheduled medical visits. Administration costs for abatacept, infliximab, and rituximab were based on the percentage of claims with a CPT-4 code for an intravenous infusion. For infusion fees, both the cost of the first hour ($143) and subsequent hours ($31/hour) were included and it was assumed that all infusions required the same amount of time per BRM, based on the distribution of administration times in the data: 1 h for abatacept, 2 h for infliximab, and 2.5 h for rituximab. CPT-4 codes for infusions were assigned to account for these costs, with 96413 (the first hour) assigned to all infusions and 96415 (an additional hour) assigned to 1 additional hour for infliximab and 1.5 additional hours for rituximab.

Concomitant non-biologic medication use and costs were not included in the model. When a patient switched to another BRM within the first year after the index date (i.e., the 12-month post-index period), the cost of the post-index BRM was included in model estimates and attributed to the total annual cost of the index BRM. For example, if a patient switched from infliximab to abatacept in the first year, the cost of abatacept (and any other BRM that the patient subsequently received in the first year) was assigned to the index infliximab treatment. The cost per patient was calculated as the total BRM expenditures in the first year divided by the number of patients who received that index BRM.

Results

Of the 69,349 patients who satisfied the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the analysis, 42,927 (62%) were continuing prior BRM therapy and 26,422 (38%) started a new BRM on the index date. The most commonly used BRMs were etanercept (32,298 patients; 47%), adalimumab (20,582 patients; 30%), and infliximab (11,157 patients; 16%); each was used more commonly than all other BRMs combined ().

Table 1. Number (%) of patients in analysis, by biologic response modifier and by condition.

Baseline characteristics are shown for subcutaneous BRMs in and for intravenous BRMs in . Most patients were enrolled in a preferred provider organization, health maintenance organization, or point-of-service plan. The most recent provider claim before the index date was usually for a visit to a rheumatologist, internist, dermatologist, or family/general practitioner. Approximately one third of patients had a provider claim categorized as ‘other’, which could include multispecialty physician groups. Baseline demographics, plan type, geographic region, and prescribing physician specialty were similar between the treatment groups. The percentage of patients who were continuing therapy at the index date, in decreasing order, was 75% for infliximab, 66% for abatacept, 64% for etanercept, 54% for adalimumab, 30% for rituximab, and 27% each for certolizumab, golimumab, and ustekinumab.

Table 2. Baseline characteristics: subcutaneous biologic response modifiers.

Table 3. Baseline characteristics: intravenous biologic response modifiers.

The cost per treated patient for each BRM relative to etanercept, overall and by condition or combination, is shown for all patients combined (continuing and new) in . Among the three TNF blockers (etanercept, adalimumab, and infliximab) that were approved for an indication within each of the conditions in the model during the study period (), the cost per treated patient across all four conditions combined in the first year after the index TNF-blocker claim was $22,722 for etanercept, $23,170 for adalimumab, and $24,601 for infliximab. For all conditions combined, the cost per patient for adalimumab relative to etanercept was 102% and the cost per patient for infliximab relative to etanercept was 108%. Within the individual conditions and combinations of conditions, the cost per treated patient for adalimumab relative to etanercept ranged from 87–109%, and for infliximab relative to etanercept ranged from 108–127%.

Figure 1. Costs per treated patient relative to etanercept. (A) Etanercept vs other TNF blockers approved for indications within RA, PsO, PsA, and AS. (B) Etanercept vs biologic response modifiers not approved for indications within all four of the conditions studied (RA, PsO, PsA, and AS). RA, rheumatoid arthritis; PsO, plaque psoriasis; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; AS, ankylosing spondylitis.

Costs relative to etanercept for the newer BRMs are shown by individual condition in . Among patients with RA, the cost per treated patient for abatacept, certolizumab, golimumab, or rituximab ranged from 90–102% relative to etanercept. The cost per treated patient was 132% for ustekinumab relative to etanercept in patients with PsO, 100% for golimumab relative to etanercept in patients with PsA, and 94% for golimumab relative to etanercept in patients with AS. The costs of newer BRMs for all conditions combined were not analyzed because many of these medications were not approved for indications within all four conditions. Costs among patients with combinations of conditions who received a newer BRM were analyzed but are not shown because of the small sample sizes (between 2–71 patients for each BRM/combination; see ).

To provide a conservative estimate of the annual cost of an index BRM, the cost of post-index therapy was included in the total cost. The contribution of post-index costs to the total cost varied by index BRM, as shown in .

Table 4. Contribution of index and post-index costs to total cost per treated patient.

Discussion

When all four conditions in this analysis were combined (RA, PsO, PsA, and/or AS), the TNF blocker etanercept was found to be both the most commonly used BRM and the least costly TNF blocker per treated patient. Although some of the newer agents had a lower cost per treated patient in some of the conditions in the analysis, they were not approved for indications within all four conditions and their usage was still limited. Comparison of costs across all four conditions combined was only possible between etanercept and the TNF blockers adalimumab and infliximab, which also had indications within all four conditions in adults. These findings were not surprising because they were consistent with those of previous cost analyses that included only etanercept, adalimumab, and infliximabCitation10–13,Citation19,Citation20,Citation25,Citation26. In each of those analyses, etanercept had the lowest cost across the four conditions studied, adalimumab had a similar or higher cost than etanercept, and infliximab was the most costlyCitation10–13,Citation19,Citation20,Citation25,Citation26. When the analysis was stratified by condition, annual costs per patient were 8–27% higher for infliximab relative to etanercept and 1–9% higher for adalimumab relative to etanercept, except among patients with PsO alone (13% lower for adalimumab relative to etanercept).

One strength of this analysis was that it was the first to include both older TNF blockers and newer BRMs, including the TNF blockers certolizumab and golimumab, as well as the drugs not operating in the TNF pathway—abatacept, rituximab, and ustekinumab. Because these BRMs were not approved for indications within all four conditions in the analysis, it was not possible to compare their overall costs across conditions. Additionally, cost comparisons for patients with combinations of conditions were removed from the analysis due to the small sample sizes for the newer BRMs (ranging from 2–71 patients each). If the costs of newer BRMs in combinations of conditions had been included in the analysis, the utility of the cost comparisons would have been limited. For example, it would not have been informative to estimate the cost per patient for patients with both PsO and PsA who received ustekinumab because it was not approved for the management of PsA. Additional treatments that were not included in the cost analysis could have been required to manage such patients.

Another strength of the analysis was the inclusion of post-index costs, which were substantial for each of the BRMs in the model. Although this approach may mask some of the potential cost benefits attributable to a specific BRM, it provides a more holistic and complete estimate of total annual BRM costs.

Despite the fact that the current analysis was designed to allow for comparisons of the cost of each medication to a single reference, it was descriptive. Because the analysis was based on a claims database, it was not possible to evaluate clinical information directly, such as disease severity or treatment outcomes. However, the disease severity specified in the indications for BRMs generally is similar and prior authorization typically is required. Thus, disease severity was not expected to vary greatly between agents, although it is possible that prescribers chose some BRMs predominantly in patients with treatment-resistant conditions and other BRMs predominantly in patients who were more likely to respond to treatment. Additionally, indirect costs, such as the costs of managing adverse events or the costs of travel to the clinic for each intravenous dose (and the associated lost time from work), were not included in the claims database and could not be included in this analysis. Costs of non-BRM treatment, such as methotrexate, were not included in the model but would not be expected to have a major influence on total annual drug costs relative to the BRMs. Another potential limitation was the imbalance in sample sizes between the older TNF blockers, etanercept (47% of patients), adalimumab (30%), and infliximab (16%), and the other five BRMs, each of which was used by fewer than 4% of patients.

The actual cost for a specific patient could be higher or lower than this estimate as a result of several factors, including the frequency of stopping index treatment, either temporarily or permanently, and the frequency of switching to another BRM. Additional analysis is needed to understand the possible influences of these factors on the cost estimates in this model.

The need for dose escalation to maintain treatment response over time may influence cost in an individual patient. Among patients with RA, it may be necessary to increase the dosing frequency for adalimumabCitation2 or the dosing frequency or dose administered for infliximabCitation3. In patients with moderate-to-severe PsO, etanercept has a 3-month loading dose, which may influence calculations of cost per treated patient among new patients relative to continuing patients. Previous analyses have demonstrated that dose modification is required more frequently for adalimumab or infliximab than for etanerceptCitation11,Citation25,Citation27–33, potentially contributing to increased costs of these medications over timeCitation11,Citation25. The frequency of administration of rituximab may also be adjusted as needed in patients with RACitation34, but the potential influence of these changes on cost relative to TNF blockers has not been reported.

Conclusions

Of the BRMs that are approved for indications within all four conditions studied (RA, PsO, PsA, and/or AS), etanercept had the lowest cost per treated patient when the drug acquisition and administration costs were assessed across all four conditions. Additional study is needed to understand how post-discontinuation treatment patterns contribute to these findings.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

Truven Health Analytics received financial support from Amgen Inc. to conduct the analysis.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

At the time of the study, GJJ and DJH were employees and stockholders of Amgen Inc. GJJ also owns stock in Pfizer Inc. MB and NP are employees of Truven Health Analytics (formerly the healthcare business of Thomson Reuters). JME Peer Reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgments

Jonathan Latham of PharmaScribe, LLC (whose work was funded by Amgen Inc.), and Dikran Toroser of Amgen Inc. provided assistance with the drafting and submission of the manuscript. The authors thank David Collier of Amgen Inc. for his critical review of the manuscript.

References

- Enbrel® (etanercept) Prescribing Information. Thousand Oaks, CA: lmmunex Corporation, 2012

- Humira® (adalimumab) Prescribing Information. North Chicago, IL: Abbott Laboratories, 2012

- Remicade® (infliximab) Prescribing Information. Malvern, PA: Centocor Ortho Biotech, Inc., 2011

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Adalimumab, etanercept and infliximab for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (NICE technology appraisal guidance 130). London: NIHCE, 2007

- Donahue KE, Jonas D, Hansen RA, et al. Drug therapy for rheumatoid arthritis in adults: an update. Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 55. (Prepared by RTI-UNC Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No. 290-02-0016-I.) AHRQ Publication No. 12-EHC025-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2012. http://www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/reports/final.cfm. Accessed April 23, 2013

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Adalimumab for the treatment of adults with psoriasis (NICE technology appraisal guidance 146). London: NIHCE, 2008

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Infliximab for the treatment of adults with psoriasis (NICE technology appraisal guidance 134). London: NIHCE, 2008

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Etanercept, infliximab and adalimumab for the treatment of psoriatic arthritis (NICE technology appraisal guidance 199). London: NIHCE, 2010

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Adalimumab, etanercept and infliximab for ankylosing spondylitis (NICE technology appraisal guidance 143). London: NIHCE, 2008

- Bullano MF, McNeeley BJ, Yu YF, et al. Comparison of costs associated with the use of etanercept, infliximab, and adalimumab for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Manag Care Interface 2006;19:47-53

- Etemad L, Yu EB, Wanke LA. Dose adjustment over time of etanercept and infliximab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Manag Care Interface 2005;18:21-7

- Gilbert TD Jr, Smith D, Ollendorf DA. Patterns of use, dosing, and economic impact of biologic agent use in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2004;5:36

- Ollendorf DA, Klingman D, Hazard E, et al. Differences in annual medication costs and rates of dosage increase between tumor necrosis factor-antagonist therapies for rheumatoid arthritis in a managed care population. Clin Ther 2009;31:825-35

- Carter CT, Changolkar AK, Scott McKenzie R. Adalimumab, etanercept, and infliximab utilization patterns and drug costs among rheumatoid arthritis patients. J Med Econ 2012;15:332-9

- Harrison DJ, Huang X, Globe D. Dosing patterns and costs of tumor necrosis factor inhibitor use for rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2010;67:1281-7

- Tang B, Rahman M, Waters HC, et al. Treatment persistence with adalimumab, etanercept, or infliximab in combination with methotrexate and the effects on health care costs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Ther 2008;30:1375-84

- Wu E, Chen L, Birnbaum H, et al. Cost of care for patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving TNF-antagonist therapy using claims data. Curr Med Res Opin 2007;23:1749-59

- Weycker D, Yu EB, Woolley JM, et al. Retrospective study of the costs of care during the first year of therapy with etanercept or infliximab among patients aged > or =65 years with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Ther 2005;27:646-56

- Bonafede MM, Gandra SR, Watson C, et al. Cost per treated patient for etanercept, adalimumab, and infliximab across adult indications: a claims analysis. Adv Ther 2012;29:234-48

- Schabert VF, Watson C, Gandra SR, et al. Annual costs of tumor necrosis factor inhibitors using real-world data in a commercially insured population in the United States. J Med Econ 2012;15:264-75

- Zeidler J, Mittendorf T, Muller R, et al. Biologic TNF inhibiting agents for treatment of inflammatory rheumatic diseases: dosing patterns and related costs in Switzerland from a payers perspective. Health Econ Rev 2012;2:20

- Claxton G, Rae M, Panchal N, et al. Employer Health Benefits: 2012 Annual Survey. Menlo Park, CA: The Kaiser Family Foundation and Health Research and Educational Trust, 2012

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare 2011 national physician fee schedule relative value file. April 2011 update. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/PhysicianFeeSched/PFS-Relative-Value-Files-Items/CMS1245669.html. Accessed July 9, 2013.

- STELARA® (ustekinumab) Prescribing Information. Horsham, PA: Janssen Biotech, Inc., 2012

- Moots RJ, Haraoui B, Matucci-Cerinic M, et al. Differences in biologic dose-escalation, non-biologic and steroid intensification among three anti-TNF agents: evidence from clinical practice. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2011;29:26-34

- Blom M, Kievit W, Fransen J, et al. The reason for discontinuation of the first tumor necrosis factor (TNF) blocking agent does not influence the effect of a second TNF blocking agent in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 2009;36:2171-7

- Schabert VF, Bruce B, Ferrufino CF, et al. Disability outcomes and dose escalation with etanercept, adalimumab, and infliximab in rheumatoid arthritis patients: a US-based retrospective comparative effectiveness study. Curr Med Res Opin 2012;28:569-80

- Bonafede MM, Gandra SR, Fox KM, et al. Tumor necrosis factor blocker dose escalation among biologic naive rheumatoid arthritis patients in commercial managed-care plans in the 2 years following therapy initiation. J Med Econ 2012;15:635-43

- Bartelds GM, Krieckaert CL, Nurmohamed MT, et al. Development of antidrug antibodies against adalimumab and association with disease activity and treatment failure during long-term follow-up. JAMA 2011;305:1460-8

- Agarwal SK, Maier AL, Chibnik LB, et al. Pattern of infliximab utilization in rheumatoid arthritis patients at an academic medical center. Arthritis Rheum 2005;53:872-8

- Berger A, Edelsberg J, Li TT, et al. Dose intensification with infliximab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Pharmacother 2005;39:2021-5

- Wu E, Chen L, Birnbaum H, et al. Retrospective claims data analysis of dosage adjustment patterns of TNF antagonists among patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Med Res Opin 2008;24:2229-40

- Ogale S, Hitraya E, Henk HJ. Patterns of biologic agent utilization among patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2011;12:204

- RITUXAN® (rituximab) Prescribing Information. South San Francisco, CA: Genentech, Inc., 2012