Abstract

Objective:

To describe the prevalence of opioid-induced constipation (OIC) in patients with cancer pain according to the Knowles-Eccersley-Scott symptom score (KESS), the different symptoms of opioid-induced bowel dysfunction (OIBD), and to assess the impact of OIBD on patient’s quality-of-life.

Methods:

A cross-sectional observational study, using the KESS questionnaire and the physician’s subjective assessment of constipation, and other questionnaires and questions on constipation, OIBD, and quality-of-life, carried out on 1 day at oncology day centres and hospitals.

Results:

Five hundred and twenty patients were enrolled at 77 centres in France; 61.7% of patients (n = 321) showed a degree of constipation that is problematic for the patient according to KESS (between 9–39). Even more patients, 85.7% (n = 438), were considered constipated according to the physician’s subjective assessment—despite laxative use (84.7% of patients). Quality-of-life was significantly reduced in constipated vs non-constipated patients for both PAC-QoL (p < 0.0001 for total score and each dimension) and the SF-12 questionnaires (statistically significant for all dimensions except physical state and role physical). OIC and OIBD led to hospitalization (16% of patients), pain (75% of patients), and frequent changes in opioid and laxative treatment.

Key limitations:

This cross-sectional study, in a selected population of cancer patients, has measured prevalence and impact of OIBD. Further confirmation could be sought through the use of longitudinal studies, and larger populations, such as non-cancer pain patients treated with opioids

Conclusions:

Cancer patients taking opioids for pain are very frequently constipated, even if they are prescribed laxatives. This leads to relevant impairments of quality-of-life.

Introduction

Opioids are very effective analgesics, frequently prescribed in cancer pain. However, their efficacy is frequently limited by their side-effects, especially gastro-intestinal (GI) onesCitation1. When opiates bind to the opiate receptors in the GI tract, they interfere with peristalsis and the mucous secretion required for bowel movementsCitation2–7. Use of exogenous opioids reduces peristalsisCitation6 which, together with reduced secretion, increased liquid reabsorption, and increased sphincter tone leads to the formation of dry, hard stools which are difficult to passCitation8. In addition to constipation, the use of opioids may induce other GI symptoms such as gastro-oesophageal reflux, abdominal cramps, spasms, and bloating, which are grouped under the heading of opioid-induced bowel dysfunction (OIBD).

Constipation is most often subjectively evaluated and objective assessment of constipation is difficult. The prevalence of constipation in cancer patients taking opioids is estimated to be between 23%Citation9 and 87%Citation10. Different scales can be useful in evaluating constipation. A significant breakthrough was made with the Knowles Eccersley Scott Symptom (KESS) scoring systemCitation11, but its length probably restricts use on a daily basis, and it is mostly used in clinical trials. An alternative brief and simple score based on three questions only, the Bowel Function Index (BFI), was recently developed and validated by Rentz et al.Citation12,Citation13 for the screening and severity assessment of opioid-induced constipation (OIC).

The impact of constipation on patients’ quality-of-life is important, especially for cancer patientsCitation14 whose quality-of-life is already significantly impaired by the illness itself. In studies, constipation has been deemed by cancer patients to be an even greater source of discomfort than the pain they sufferedCitation15. A questionnaire measuring the impact of constipation on quality-of-life has recently been validated: the Patient Assessment of Constipation Quality-of-Life (PAC-QoL)Citation16. This tool allows more accurate measurement of the discomfort caused by constipation and should aid physicians in dealing with this iatrogenic effect. The development of new validated and simple tools dedicated either to symptoms or quality-of-life related to constipation may help to make a more precise clinical analysis of constipation in patients.

The main objective of the DYONISOS study (DYsfonctiONs Intestinales induiteS par les OpioïdS forts) upon which this manuscript is based was to describe, in patients with cancer, the prevalence of OIC according to KESS criteria. Secondary objectives aimed to describe the different symptoms which indicate OIBD, the impact of constipation on health economic aspects, and the impact of OIBD on quality-of-life as assessed by the generic SF-12 questionnaire and the specific quality-of-life score (PAC-QoL).

This paper focuses firstly on the prevalence of OIC and secondly on the symptoms of OIBD and their impact on quality-of-life. Furthermore, OIC was assessed subjectively by the physician. The result of this assessment served as a basis for further analyses of KESS and BFI values in the study population. The correlation between the severity of constipation as assessed by the physician and as assessed by the Bowel Function Index (BFI) and KESS scores was also investigated, but is discussed elsewhereCitation17.

Methods

Selection of physicians and patients

This cross-sectional study was conducted by 77 physicians (oncologists, pain specialists, palliative care specialists) working in public or private hospitals and outpatient facilities located all over France. Consecutive patients with cancer pain, who were taking strong opioids at the time of the visit, who were either hospitalized or treated as outpatients, and who gave consent, were included in the study between 9 June 2009 and4 June 2010. Patients were not included if they had participated in another epidemiological survey or in a clinical trial on opioids or constipation, or if they were not able to answer the questionnaires.

Study sample size

The sample size was calculated based on the number of patients required to determine the prevalence of constipation in patients with cancer pain and taking strong opioids. Data published in the literature show great variations from one study to the next of between 23%Citation9 and 84%Citation18. Assuming a hypothesis of a 40% prevalence of constipation in patients, to describe this frequency with a 95% confidence interval, with an accuracy of 5% and a significance level of 0.05, 369 patients would be required. However, taking into account a potential dropout rate of 25%, the total number of patients required was adjusted to 492.

Data gathered and evaluation criteria

Patient characteristics

Physicians were asked to record patients’ demographic information (age, sex, socio-economic status), type of cancer (type, with or without metastases), treatment (surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, palliative treatment), strong opioids prescribed (start date, type, dosage), and any bowel dysfunction experienced prior to the prescription of opioids.

Main criteria

Patient constipation (primary end-point) was evaluated using the KESS constipation questionnaire at the time of visit. The KESS constipation questionnaire is composed of 11 questions, and is scored on a scale of 0–39. The 11 items of the KESS questionnaire investigate various characteristics of constipation. A score of 9 or above indicates the presence of constipationCitation19.

Secondary criteria focused on:

Prevalence of different symptoms of OIBD.

OIC/OIBD management and impact of OIC/OIBD on pain (assessed using a numerical rating scale, NRS, with 0 = no pain, and 10 = unbearable pain), opioid treatment, hospitalizations, and laxative intake.

Impact of OIC/OIBD on quality-of-life, evaluated using the generic SF-12 questionnaire and the specific PAC-QoL score. Global impact of bowel dysfunction on patient’s quality-of-life was evaluated using a NRS (0 = no repercussions, 10 = unbearable repercussions). The PAC-QoL questionnaire specifically examines how quality-of-life is altered by constipation. This is a 28 item-questionnaire, exploring the total impact of constipation on a patient’s quality-of-life (0 = no impact, 4 = great impact) and includes worry, physical consequences, social life, and patient satisfactionCitation19. The SF-12 questionnaire is a generic quality-of-life scaleCitation20 with eight aspects (physical function, role physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social function, role emotional, and mental health). These scores are also grouped into two overall dimensions: physical state and mental state.

As additional analyses, patient constipation was evaluated subjectively by the physician (four scores: not at all, slightly to moderately, very, and extremely constipated), and the BFI was administered to the patient. For the BFI, the physician questioned the patients and recorded their answers. The BFI looks at constipation over the past 7 days using a NRS (0–100). The index is the average value of three items, as follows:

Ease of defecation (0 = easy/no difficulty–100 = severe difficulty);

Feeling of incomplete bowel evacuation (0 = not at all–100 = very strong); and

Personal judgement of constipation (0 = not at all–100 = very strong).

An index over 28.8 is predictive of constipationCitation20.

Statistical analysis

Once patients’ demographic and clinical information had been recorded, the statistical analysis provided the prevalence of constipation, as defined by KESS score and subjective evaluation of the physician. Means of the KESS score and BFI score were compared between the levels of constipation according to the subjective assessment of the physicians (not at all, slightly-to-moderately, very, extremely) with an ANOVA test. The analysis then provided the PAC-QoL and SF-12 quality-of-life scores and comparison between patients with or without constipation according to physician’s subjective assessment with a Student t-test. All statistical analyses were carried out using SAS software version 9.2.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 520 patients were enrolled in the study by 77 investigating physicians. The age, sex, and other characteristics of these patients, including the most common cancers from which they suffered, are included in . One hundred and fifty-six patients (30.4%), 21.3% of men, 41.0% of women, had already suffered from bowel dysfunction prior to their diagnosis of cancer (missing: n = 4). In 122 of these cases, the bowel dysfunction was constipation, and 108 had already been treated for it, usually with laxatives (n = 89).

Table 1. Characteristics of the study population.

On the day of the study that the questionnaire was completed, two thirds of patients (67.3%, n = 348) presented with factors likely to cause constipation apart from opioid treatment, in particular they were permanently bedbound (45.4%), the cancer or metastasis was gastro-intestinal (44.5%) or peritoneal (20.1%), they were taking another medication likely to cause constipation (18,6%), they were suffering from dehydration (15.9%), they were suffering from a neuropathic disorder (11.5%), or they had undergone recent GI surgery (9.7%).

The average duration of opioid treatment before study inclusion was 4.4 (SD 6.7) months (range = 3 days to 6 years). In most cases (77.4%), only one opioid had been taken and the most common of these were oxycodone (32.4%), morphine (30.9%), and fentanyl (13.7%), but other patients had taken more than one opioid at a time (e.g., fentanyl + morphine: 13.7%). Over two thirds of patients (68.3%) were prescribed a combination of prolonged-release (PR) and immediate-release (IR) medications. Patients were also prescribed Step 1 analgesics (55.4%), steroids (42.8%), antidepressants (25.2%), anticonvulsants (23.4%), anxiolytics (29.1%), non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (13.5%), and antispasmodics (13.2%) in addition to their opioid treatment.

Prevalence and symptoms of OIC according to KESS criteria

The KESS questionnaire scores patients on their level of constipation, ranging from 0 = no constipation to 39 = maximum constipation. A score of 9 or above indicates a level of constipation that is problematic for the patient. At the time of the study 61.7% (321) of patients in the study had a KESS score of between 9–39 points and, therefore, had constipation at a level that was problematic. When all the patients in the study were included the mean score was 11.3 (SD = 6.8) and the median score was 11.0 (range = 0–33). The overall KESS score is compiled from the answers to various questions about bowel function and constipation, which can also be examined individually. The responses to these questions are shown in .

Table 2. KESS questionnaire responses.

Prevalence of OIC according to the physician’s subjective assessment

OIC was also looked at in a subjective assessment carried out by the investigating physicians. Therefore, according to the investigating physicians’ assessments, 85.7% (n = 438) of patients were considered to be constipated; including 48.7% who were slightly-to-moderately constipated, 33.3% who were very constipated, and 3.7% who were extremely constipated.

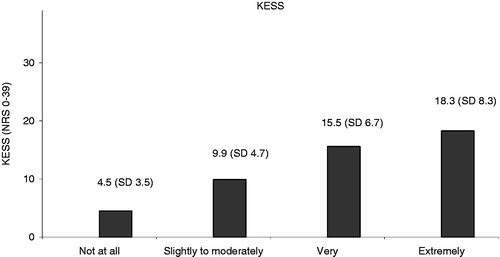

KESS score values in the study population

The mean KESS score for the total population in the study was 11.3 (SD = 6.8) (n = 520). The mean KESS scores of two groups of patients (constipated vs non-constipated according to the physician’s subjective assessment) were compared. It was shown that the mean KESS score was significantly higher for patients who were constipated according to the physician’s subjective assessment. In patients who were considered constipated, the KESS score was 12.5 (SD = 6.5) (n = 438). In patients who were not considered constipated, the KESS score was an average of 4.5 (SD = 3.5) (n = 73) (p < 0.0001, t-test).

An ANOVA test compared the mean KESS scores with the level of constipation as assessed subjectively by the physician (not at all, slightly-to-moderately, very, extremely), and this also shows that the mean KESS score increased significantly with the level of constipation, as assessed by the physician ().

BFI score values in study population

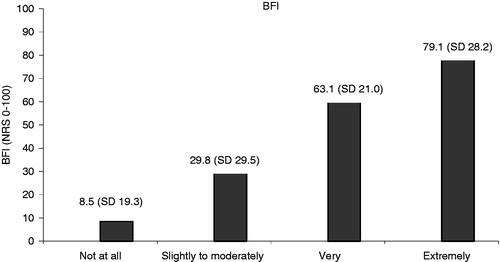

The average BFI score in the total population was 39.7 (SD = 29.1) (n = 520). BFI scores between 0–28.8 represent a reference range that covers 95% of a normal, non-constipated population. Three hundred and four (58.5%) patients in this study showed BFI values above this reference range. In the patients who were considered constipated in the subjective opinion of the physician, the average BFI score was 44.8 (SD = 27.0) (n = 438); in those who were not considered constipated by the physician the average BFI score was 8.5 (SD = 19.3) (n = 73) (p < 0.0001, t-test), significantly lower. An ANOVA test compared the mean BFI scores for the different levels of constipation as subjectively assessed by the physician. This again showed that the mean BFI score increased significantly with the level of constipation as assessed by the physician ().

Prevalence of different symptoms of OIBD

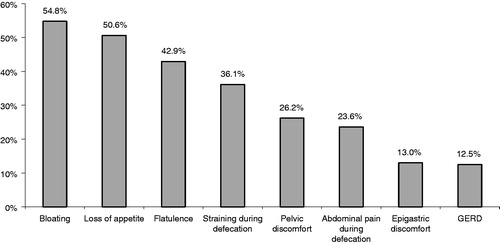

Bowel dysfunction symptoms (apart from constipation) were present in 74.9% of patients (n = 385): bloating (54.8%), loss of appetite (50.6%), flatulence (42.9%), straining during defecation (36.1%), pelvic discomfort (26.2%), pain during defecation (23.6%), epigastric discomfort (13.0%), and gastro-esophagal reflux (12.5%) ().

Impact of constipation on health economic aspects

OIC management

Six patients out of 520 did not complete the questionnaire on the consequences of constipation and bowel dysfunction because they felt that they had no symptoms. Before the visit, constipation and/or other symptoms of bowel dysfunction induced by opioids had led 84.7% of all patients in the study to take laxatives: on almost a daily basis for 51.4%, 2- or 3-times a week for 23.1%, and once a week for 10.2% of these patients; 15.3% of all patients had taken no laxatives. According to the KESS questionnaire, over one third of patients in the study (37.1%) had already required an enema or used suppositories at least once prior to entering the study.

All numbers related to constipated patients, below, concern the 438 patients who were subjectively assessed as constipated by the physician.

Laxative intake

In the group of constipated patients, roughly nine out of 10 patients (94.1% of the very or extremely constipated patients) were taking laxatives at the time of the study, with at least 54.1% of patients taking them daily or almost daily (66.7% in those who were very or extremely constipated).

Frequency of hospitalization

Constipation and/or other symptoms of bowel dysfunction had already led to previous hospitalization in 8% of constipated patients, and were responsible for current hospitalization in 8% of cases (vs, respectively, 13.4 and 15.1% of the very or extremely constipated patients).

Pain and strong opioid prescriptions

Three quarters of constipated patients (84.9% of the very or extremely constipated patients) experienced pain connected with this disorder, evaluated at, on average, 3.4 (SD = 1.9) on an NRS of 0–10 (4.1 (SD = 2.1) for the very or extremely constipated patients). This pain was reported to be moderate-to-severe (≥4/10) in 36.6% of patients, and for 19.1% of them a change in the strong opioid treatment would have been considered if the pain persisted (vs, respectively, 49.1% and 25.2% for the very or extremely constipated patients). Constipation and/or other symptoms of bowel dysfunction had already affected the intake of strong opioids in patients, leading to diminished dosage in 10.2% (14.1% of the very or extremely constipated patients), irregular intake in 7.5% (8.6% of the very or extremely constipated patients), and discontinuation of treatment 5.4% (8.1% of the very or extremely constipated patients). When opioid treatment was altered, this led to increased pain in at least 86% of these patients.

Changes of opioid and laxatives treatment prescribed during the visit

Constipation and/or other symptoms of bowel dysfunction led to treatment changes in at least seven out 10 constipated patients during the visit. For 58.8% of patients (65% of the very or extremely constipated patients), laxatives were prescribed, and for 10.5% of patients (12.5% of the very or extremely constipated patients), the opioid treatment was changed: change of opioid 7.4%, decrease dose of the opioid 2.4%, opioid temporarily discontinued 0.7% (vs, respectively, 10.4%, 1.6%, and 0.5% of the very or extremely constipated patients).

Impact of constipation on quality-of-life

According to patient global assessment, 93.2% of constipated patients reported that constipation and/or other symptoms of bowel dysfunction had altered their quality-of-life (≥1/10 using a NRS with 0 = no repercussion and 10 = unbearable repercussions). This alteration was rated on average at 3.0 (SD = 2.2) (4.3 (SD = 2.3) for the very or extremely constipated patients), and 38.3% (59.5% of the very or extremely constipated patients) considered the impact of constipation/bowel dysfunction to be moderate-to-severe (≥4/10).

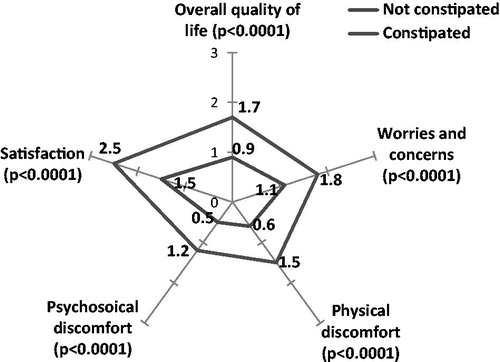

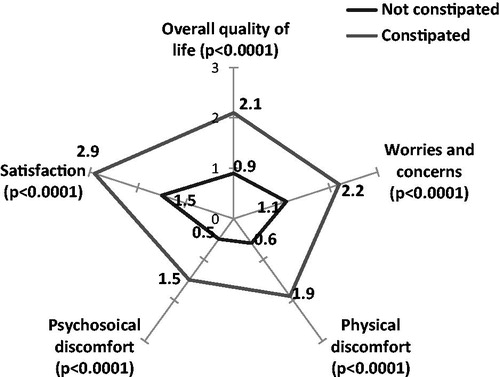

The PAC-QoL questionnaire evaluates the impact of constipation on overall quality-of-life (0: no impact, 4: major impact). The PAC-QoL results demonstrate that overall quality-of-life was significantly worsened in constipated patients compared to non-constipated patients (1.7 (SD = 0.7) vs 0.9 (SD = 0.5), p < 0.0001) (), especially for very or extremely constipated patients (2.1 (SD = 0.7)) ().

Figure 5. Quality-of-life in very and extremely constipated patients compared to non-constipated patients (PAC-QoL).

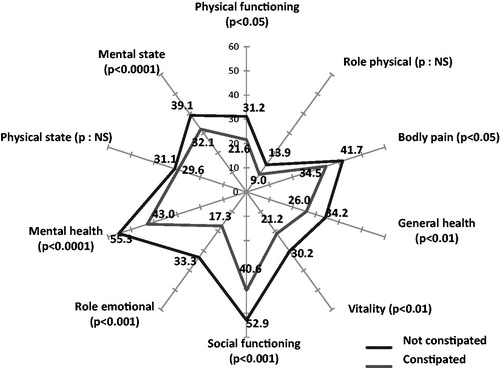

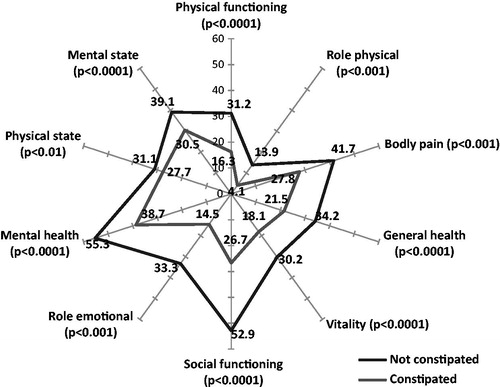

The SF-12 results demonstrate that the quality-of-life in constipated patients was also worsened, since only four dimensions of the SF-12 scale were over 30 (mental health, social function, body pain, and mental state) and none were over 50. Role physical and role emotional were the most altered dimensions (). For patients who were very or extremely constipated, all dimensions were significantly altered vs non-constipated patients ().

Discussion

This study assessed the prevalence and impact of OIC in patients with cancer pain according to the KESS questionnaire and the prevalence of different symptoms of OIBD.

There are several tools available to assess constipation, and specifically OIC, including the KESS and BFI questionnaireCitation13,Citation16,Citation19,Citation21,Citation22. The KESS and BFI questionnaires are validated tools that cover a certain timeframe and certain aspects of the pathology of OIC. The two questionnaires have the clear advantage that they assess OIC from the patient’s perspective, and therefore cover subjective criteria from the patient’s point of view, like impact and severity of symptoms. These tools allow a quantitative assessment of constipation indicated by values >28.8 for the BFI and >9 for the KESSCitation11,Citation19,Citation20. They are, therefore, appropriate for assessing the severity of constipation.

However, in this study, for a global evaluation of the prevalence of OIC in a population, the physician’s subjective assessment served as a basis. The subjective assessment of the physician does not adhere to pre-defined criteria and is likely to cover a population of constipated patients in a broader context. With the clear time dependency of the KESS and BFI questionnaires they aim to assess, at least in certain sub-questions, the acute situation of patients. This is different to the subjective assessment of the physician who could have considered patients as constipated on the basis of their medical condition or medication (laxative treatment), even if they were not presenting any other signs of constipation at the time of the visit. This would lead to lower KESS, and especially BFI values, in these ‘constipated’ patients. As in this study the clinical evaluation of the general phenomenon of OIC was of interest, this paper focuses largely on the group of patients who were considered as constipated in the opinion of the physician, and then examines the results of the KESS and BFI scores, and quality-of-life aspects, on that basis.

A major difficulty when evaluating the prevalence of OIC in patients is the number of factors that can affect and cause constipation, such as pre-existing conditions and physical factors, including being bed-bound or dehydrated. In this study 78.6% of patients had advanced cancer and were in palliative or end of life care so factors such as these would have played a part in this patient population. In addition, many patients were chronically constipated; 23.2% had experienced constipation for more than 18 months. However, if the physicians’ subjective assessment that 85.7% of patients were constipated is taken as a reference, this is similar to what has been found in other studies, such as the PROBE study carried out by Bell et al.Citation23, where constipation was present in 81% of subjects, and in the SykesCitation10 study, where 87% of patients taking strong opioids required laxatives to relieve constipation.

When looking at the KESS scores and the BFI scores from this study it is clear that the scores are higher in the patients who were considered as constipated by the physician than in the entire study population. The differences in KESS and BFI scores between the patients that were considered as constipated according to the physician’s subjective assessment and those that were not constipated was significant. The high KESS and BFI scores seen in this study also indicate that, although laxatives were used frequently (almost 9 out of 10 constipated patients were treated with laxatives at the time this study was undertaken and over half of these patients took them almost every day), they were inefficient against OIC. However, the study does not provide information on whether health management was optimized at the time the questionnaire was undertaken, nor on the type and number of laxatives used.

Looking at the BFI and KESS values and the prevalence of OIC as assessed subjectively by the physician, it becomes clear that only some patients subjectively classed as constipated by their physician presented BFI values that differed from those of a population of non-constipated chronic pain patients (BFI normal range) (58.5%) and KESS values at a level that is problematic for the patients (67.1%). In part, this results from the different approaches of the three methods of assessment. The KESS, and especially the BFI, relate to a more acute situation. The BFI, with its three sub-dimensions, concentrates on a timeframe of 7 days before filling in the questionnaire. The KESS combines questions on a broader timeframe (e.g., duration of constipation) with questions on the acute situation (e.g., stool consistency). The physician’s subjective assessment covers a global impression and does not necessarily reflect acute symptoms. These differences in assessment are reflected in this study when looking at the stepped results for the BFI (58.8%; acute situation), KESS (67.1%; acute and ‘global’ situation) and the subjective assessment (85.7%; more ‘global’ situation). However, all three assessment tools show a good correlationCitation17. Tools such as the KESS questionnaire and the BFI can help to make a more accurate diagnosis of constipation in the specific case of OIC. In addition the BFI is a simple score to use, consisting as it does of only three items. These tools can be of help in enabling physicians to quantify OIC.

Currently, preventive treatment for constipation usually consists of prescribing laxatives, but recommendations diverge when constipation requires treatment in patients taking opioids, particularly those with cancer or in palliative care. Use of one or two different laxatives, the combination used, and whether to use suppositories are aspects that vary from one recommendation to the next. Also, although official recommendations advise systematic laxative treatment throughout opioid treatment, use remains irregular. A study undertaken in France on the first prescription of strong opioids by oncologists to 1038 patients showed that a laxative was only prescribed for one patient in fourCitation24.

This lower effectiveness of laxatives should be considered along with the fact that the laxatives do not counteract the root problem of constipation caused by opioidsCitation8, i.e., they have no effect on the specific pharmacological binding of opioids to gastrointestinal opioid receptors, and they also have frequent side-effects. In a study of 2055 patients taking opioids, Cook et al.Citation25 showed that about one quarter of respondents were not satisfied with the laxatives available and 45% of patients using them reported diarrhoea or urgency. Pappagallo.Citation26 compared patients suffering from constipation caused by opioids with a control group of constipated patients, and showed that laxatives only relieved 46% of patients suffering from opioid-induced constipation, while 84% of control patients obtained relief.

OIC is the most well known symptom of OIBD, but it is by no means the only one. This study looked at other symptoms of OIBD that can cause problems. The experience of pain in cancer patients with OIBD is complex as they are taking opioids to combat cancer pain, but the OIC and OIBD can cause pain in their own right. As indicated by FallonCitation15, constipation is at times considered by patients to cause greater discomfort than the pain caused by their underlying condition. It was noted that three quarters of constipated patients in this study experienced pain caused by their constipation.

All of this can have an impact on opioid treatment compliance and can cause a very ambivalent attitude to opioid treatment, which varies between reducing and increasing opiates, or even rotating opiates, according to the degree of constipation; a situation not conducive to constant pain reduction (85.7% of patients in this study experienced increased pain while adapting opioids in order to control their OIBD). This phenomenon was reported by Candrilli et al.Citation27, who demonstrated in a retrospective analysis that opioid-treated constipated cancer patients (n = 821), when compared with a similar non-constipated group (n = 821), were more likely to take more than two opioids simultaneously (44% vs 31%; p < 0.0001), discontinued then restarted opioids more frequently (36% vs 27%; p < 0.0002), or rotated opioids (54% vs 36%; p < 0.0001).

Taken together, the consequences of OIC and OIBD lead to increased hospitalization rates, laxative intake, etc. This might have a significant impact on health economic aspects, as it can lead to increased treatment costs.

The quality-of-life of these cancer patients was an important aspect of this study, and 93.2% of constipated patients said that OIC/OIBD had adversely affected their quality-of-life, particularly in physical and emotional ways. Each of the specific dimensions of the PAC-QoL and most of those of the SF-12 generic quality-of-life questionnaire showed a statistically significantly change for constipated patients compared to non-constipated patients, even though the SF-12 is not a constipation-specific questionnaire, thus confirming the strong burden of OIC/OIBD. Those patients who were classed as ‘very’ or ‘extremely’ constipated were also the patients whose quality-of-life was affected most severely. We have no data showing, like Bell et al.Citation28, that opioid-induced constipation has repercussions on professional life, but the major impact on the social dimension of the PAC-QoL observed in our study probably reflects this effect. In a study undertaken on 2430 patients who had been taking opioids for over 6 months for chronic pain, Bell et al.Citation28 showed that, compared with non-constipated patients, constipated patients consulted their physician more frequently (mean difference 3.84 visits; p < 0.05), reported significantly greater time missed from work, impairment while working, overall work impairment, and activity impairment (p < 0.05 for all comparisons). On the other hand, our study showed that constipation caused by opioids was or is responsible for 16% of hospitalizations. A retrospective analysis in the US of 237,447 non-cancer patients treated with opioids for other conditions also confirms that patients suffering from gastro-intestinal side-effects were hospitalized significantly more often, spent more time in hospital, and were admitted to emergency more (p < 0.001 throughout) when compared to those not suffering from these secondary effectsCitation29.

Conclusion

Cancer patients taking opioids for pain are very frequently constipated, even if they are prescribed laxatives. As well as constipation, OIBD frequently manifests as other symptoms such as bloating, loss of appetite, and flatulence. It also causes pain. Furthermore, it can limit the use of analgesics, adversely affect quality-of-life, and may require hospitalization and, thereby, lead to increased health economic costs. Accurate methods of constipation assessment specifically tailored to OIC/OIBD are required to help with management of symptoms.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was designed and financed by Mundipharma SAS France and conducted under the sponsorship of Mundipharma SAS France.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

LA and SP were principal co-ordinators of this study and received fees from Mudiphama SAS France for participation to the study. LA has been a momentary board member and SP has been a board member for Mundipharma SAS. NB, LL, and VG participated as investigators in this study. NB has received honoraria as a speaker for Mundipharma symposium. LL has received honoraria as a speaker for Mundipharma meetings. BC was an employee of Mundipharma SAS France. CC is an employee of Mundipharma SAS France. All authors were involved in the development and writing of the manuscript. JME Peer Reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgments

Written with the assistance of Hazel Olway, a Medical Writer at Mundipharma Research Ltd., and Catharina Buschmann-Kramm, R&D Communication Manager at Mundipharma Research GmbH & Co.KG. Petra Leyendecker, Michael Hopp, Catharina Buschmann-Kramm, and Björn Bosse (Mundipharma Research GmbH & Co. KG) gave expert input into the discussion of the results.

Notes

†BFI Copyright 2002, Mundipharma GmbH, City, Country; BFI is subject of European Patent Application Publication No. EP 1,860,988 and corresponding patents and applications in other countries.

*PAC-QOL, Janssen Global Services, LLC, City, State, Country, USA.

References

- World Health Organization. Cancer pain relief. Geneva: WHO, 1996

- De Luca A, Coupar IM. Insights into opioid action in the intestinal tract. Pharmacol Therapeut 1996;69:103-15

- De Schepper HU, Cremonini F, Park MI, et al. Opioids and the gut: pharmacology and current clinical experience. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2004;16:383-94

- Holzer P. Opioids and opioid receptors in the enteric nervous system: from a problem in opioid analgesia to a possible new prokinetic therapy in humans. Neurosci Lett 2004;361:192-5

- Holzer P. Treatment of opioid-induced gut dysfunction. Exp Opin Investig Drugs 2007;16:181-94

- Mehendale SR, Yuan CS. Opioid-induced gastrointestinal dysfunction. Dig Dis 2006;24:105-12

- Wood JD, Galligan JJ. Function of opioids in the enteric nervous system. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2004;16:17-28

- Panchal SJ, Muller-Schwefe P, Wurzelmann JI. Opioid-induced bowel dysfunction: prevalence, pathophysiology and burden. Int J Clin Pract 2007;61:1181-7

- Meuser T, Pietruck C, Radbruch L, et al. Symptoms during cancer pain treatment following WHO-guidelines: a longitudinal follow-up study of symptom prevalence, severity and etiology. Pain 2001;93:247-57

- Sykes NP. The relationship between opioid use and laxative use in terminally ill cancer patients. Palliative Med 1998;12:375-82

- Knowles CH, Scott SM, Legg PE, et al. Level of classification performance of KESS (symptom scoring system for constipation) validated in a prospective series of 105 patients. Dis Colon Rectum 2002;45:842-3

- Rentz AM, van Hanswijck de Jonge P, Leyendecker P, et al. Observational, nonintervention, multicenter study for validation of the Bowel Function Index for constipation in European countries. Curr Med Res Opin 2011;27:35-44

- Rentz AM, Yu R, Muller-Lissner S, et al. Validation of the Bowel Function Index to detect clinically meaningful changes in opioid-induced constipation. J Med Econ 2009;12:371-83

- Choi YS, Billings JA. Opioid antagonists: a review of their role in palliative care, focusing on use in opioid-related constipation. J Pain Symptom Manage 2002;24:71-90

- Fallon MT. Constipation in cancer patients: prevalence, pathogenesis, and cost-related issues. Eur J Pain 1999;3:3-7

- Marquis P, De La Loge C, Dubois D, et al. Development and validation of the Patient Assessment of Constipation Quality of Life questionnaire. Scand J Gastroenterol 2005;40:540-51

- Abramowitz L, Béziaud N, Caussé C, et al. Further validation of the psychometric properties of the Bowel Function Index for evaluating opioid-induced constipation (OIC). J Med Econ 2013;16:1434-41

- McMillan SC. Assessing and managing opiate-induced constipation in adults with cancer. Cancer Control 2004;11:3-9

- Knowles CH, Eccersley AJ, Scott SM, et al. Linear discriminant analysis of symptoms in patients with chronic constipation: validation of a new scoring system (KESS). Dis Colon Rectum 2000;43:1419-26

- Ueberall MA, Müller-Lissner S, Buschmann-Kramm C, et al. The Bowel Function Index for evaluating constipation in pain patients: definition of a reference range for a non-constipated population of pain patients. J Int Med Res 2011;39:41-50

- McCrea GL, Miaskowski C, Stotts NA, et al. Review article: self-report measures to evaluate constipation. Aliment Pharm Therap 2008;27:638-48

- Coffin B, Caussé C. Constipation assessment scales in adults: a literature review including the new Bowel Function Index. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011;5:601-13

- Bell TJ, Panchal SJ, Miaskowski C, et al. The prevalence, severity, and impact of opioid-induced bowel dysfunction: results of a US and European Patient Survey (PROBE 1). Pain Med 2009;10:35-42

- Krakowski I, Delorme T, Vuillemin N, et al. [Observational study of the initial prescription of level 3 analgesics in cancer patients.]. Bull Cancer 2009;96:59-66

- Cook SF, Lanza L, Zhou X, et al. Gastrointestinal side effects in chronic opioid users: results from a population-based survey. Aliment Pharm Therap 2008;27:1224-32

- Pappagallo M. Incidence, prevalence, and management of opioid bowel dysfunction. Am J Surg 2001;182:11S-18S

- Candrilli SD, Davis KL, Iyer S. Impact of constipation on opioid use patterns, health care resource utilization, and costs in cancer patients on opioid therapy. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother 2009;23:231-41

- Bell T, Annunziata K, Leslie JB. Opioid-induced constipation negatively impacts pain management, productivity, and health-related quality of life: findings from the National Health and Wellness Survey. J Opioid Manag 2009;5:137-44

- Kwong WJ, Diels J, Kavanagh S. Costs of gastrointestinal events after outpatient opioid treatment for non-cancer pain. Ann Pharmacother 2010;44:630-40