Abstract

Objective:

Healthcare costs of inflammatory bowel disease are substantial. This study examined the effect of adherence versus non-adherence on healthcare costs in patients with inflammatory bowel disease.

Methods:

Adults who started infliximab treatment between 2006 and 2009 and had a diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease were identified from MarketScan Databases. Medication adherence was defined as an infliximab medication possession ratio of 80% or greater in the first year. Mean treatment effects (adherence versus non-adherence) on costs in adherent patients were estimated with propensity-weighted generalized linear models.

Results:

A total of 1646 patients were identified. Significant variables in the model used to develop propensity weights were age, year of infliximab initiation, having Medicare coverage, presence of supplementary diagnoses, office as the place of service for infliximab initiation, prior aminosalicylate use, prior outpatient costs, number of prior outpatient visits, and number of prior colonoscopies. Mean total costs in adherent (n = 674) and propensity-weighted non-adherent (n = 972) patients were $41,713 versus $47,411 overall (p < 0.001), including $28,289 versus $14,889 for infliximab drug costs (p < 0.001), $2458 versus $17,634 for hospitalizations (p < 0.001), $7357 versus $10,909 for outpatient visits (p < 0.001), $236 versus $458 for emergency room visits (p < 0.001), and $3373 versus $3521 for other pharmaceuticals costs (p = 0.460).

Limitations:

Costs associated with infliximab administration (infusions, adverse events) were captured in healthcare costs (inpatient, outpatient, and emergency room), not in infliximab costs. The influence of adherence on indirect costs (e.g., time lost from work) could not be determined. Reasons for non-adherence were not available in the database.

Conclusions:

In patients who were adherent to infliximab treatment (a medication possession ratio of 80% or greater in the first year), adherence versus non-adherence was associated with lower total healthcare costs, supporting the overall value of infliximab adherence in patients with inflammatory bowel disease.

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease is an immune-mediated inflammatory disorder that includes Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitisCitation1. In the United States, an estimated 1 million people have inflammatory bowel disease and the prevalence is approximately 500 per 100,000 adultsCitation2. In 2006, the total economic burden of inflammatory bowel disease in the United States was between $19.0 billion and $30.4 billion, including $10.9–15.5 billion for Crohn’s diseaseCitation3 and $8.1–14.9 billion for ulcerative colitisCitation4.

In inflammatory bowel disease, innate cells produce increased levels of tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα)Citation1. Infliximab neutralizes the biological activity of TNFα by binding with high affinity to the soluble and transmembrane forms of TNFα and inhibits binding of TNFα with its receptorsCitation5. In the United States, indications for the use of infliximab in adults with inflammatory bowel disease include the following: reducing signs and symptoms and inducing and maintaining clinical remission in adult patients with moderately to severely active Crohn’s disease who have had an inadequate response to conventional therapy; reducing the number of draining enterocutaneous and rectovaginal fistulas and maintaining fistula closure in adult patients with fistulizing Crohn’s disease; and reducing signs and symptoms, inducing and maintaining clinical remission and mucosal healing, and eliminating corticosteroid use in adult patients with moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis who have had an inadequate response to conventional therapyCitation5.

A systematic review of the available evidence concluded that 30% of patients with inflammatory bowel disease who receive infliximab treatment are non-adherentCitation6. When stringent criteria for adherence are applied, such as missing more than one dose in the first year, rates of non-adherence in the first year may be as high as 60%Citation7. Several studies have reported that infliximab non-adherence in patients with Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis is associated with greater healthcare utilization and greater costCitation8–11. Each of those studies focused on patients who received at least four doses of infliximabCitation8,Citation11, or who continued on infliximab treatment for at least 56 daysCitation9,Citation10, to assess the costs of non-adherence among patients who received maintenance treatment with infliximab. Most of the studies reported the costs of hospitalizationCitation8–10; only one examined the total cost of care associated with infliximab non-adherenceCitation11. None of the studies attempted to control for baseline differences between adherent and non-adherent patients.

The purpose of this study was to examine the treatment effect of infliximab adherence and healthcare costs from the payer perspective in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. A propensity-weighted cost model was used to improve upon the existing literature by adjusting for pre-existing differences between adherent and non-adherent patients.

Patients and methods

Data source

Data were analyzed from the Truven Health MarketScan 2005 to 2010 Commercial Claims and Encounters and Medicare Supplemental and Coordination of Benefits Databases. These databases represent the health services of employees, dependents, and retirees in the United States with primary or Medicare supplemental coverage through privately insured fee-for-service, point-of-service, or capitated health plans from approximately 100 payers with more than 500 million claim records available. The databases are HIPAA compliant and contain fully integrated patient-level data, including inpatient, outpatient, drug, lab, health and productivity management, health risk assessment, dental, and benefit design.

Sample selection

The analysis included patients who received infliximab between January 2006 and December 2009, as identified by one or more claims with the Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) code J1745 (infliximab 10 mg). For each patient, the index date was the date of the first claim with this code, the pre-index period was 360 days before the index date, and the post-index period was 360 days on or after the index date. To be eligible for inclusion, patients were continuously enrolled in the health plan for at least 360 days before and at least 360 days after the index date. All patients were at least 18 years of age and had either two or more claims on different dates with a diagnosis of Crohn’s disease (ICD-9-CM: 555.XX) or two or more claims on different dates with diagnosis of ulcerative colitis (ICD-9-CM: 556.XX) during the pre-index period. Patients with exactly one claim for Crohn’s disease and exactly one claim for ulcerative colitis in the pre-index period were not included in the analysis. Patients with two or more claims for Crohn’s disease and two or more claims for ulcerative colitis in the pre-index period were considered to have Crohn’s disease.

Key exclusion criteria were any prior claim for infliximab during the pre-index period or a claim with a diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis (ICD-9-CM: 714.xx) at any time during the study period (i.e., from 2005 through 2010). Patients with a prescription claim for infliximab that was billed with a National Drug Code (NDC) of 57894003001 were excluded because infusion dates for these patients were unknown. Patients were excluded if they had any claim during the study period for adalimumab or certolizumab pegol, which were approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of Crohn’s disease at the time of the analysis.

Costs

Cost components are summarized in . The primary outcome was total costs during the 360 day post-index period from the payer perspective, including infliximab drug acquisition costs, inpatient costs, outpatient costs, emergency room, and pharmacy costs. Costs were summarized for the 360 day pre-index period (baseline analysis) and 360 day post-index period (outcome analysis) for each patient. Because these periods could occur between January 2005 and December 2010, discounting was applied, adjusting all costs to December 2010.

Table 1. Cost components during the 360 day post-index period for each patient.

Disease-related costs were evaluated as a subset of all-cause costs and were identified from outpatient, inpatient, or emergency room claims with a diagnosis of Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis in the primary diagnosis field. Additionally, outpatient and inpatient claims were considered disease-related if they included a HCPCS code for infliximab or a code for one of the following bowel procedures: bowel incision, bowel resection, colectomy (complete or partial), ostomy fistula repair, or other major abdominal or bowel surgery. Disease-related pharmaceuticals were identified from pharmacy claims for aminosalicylates, azathioprine, corticosteroids, cyclosporin, 6-mercaptopurine, methotrexate, metronidazole, mycophenolate mofetil, or tacrolimus.

Adherence calculation

The medication possession ratio (MPR) was calculated as follows:

The number of days of infliximab therapy was the sum of unduplicated days of therapy during the 360 day post-index period, based on infusion dates and duration of action. The duration of action for infliximab was assumed to be 14 days for the first infusion, 28 days for the second infusion, and 56 days for all subsequent infusions, based on the approved labeling for infliximab in the United StatesCitation5 and the fact that patients had received no infliximab therapy in the 360 day pre-index period. If the time between the first and second infusions exceeded 30 days, the time between the second and third infusions exceeded 60 days, or the time between any subsequent infusions exceeded 90 days, it was assumed the therapy cycle was restarted; the next infusion after this gap had an assumed duration of action of 14 days.

If claims were closer than the assumed duration of action, only the actual number of days between claims was counted. When the calculated ending date for a claim (date of service plus the days supply) exceeded the end of the observation period (index date +360) the end of observation date was used as the ending date for the claim. The adherent group included all patients whose MPR was 80% or greater and the non-adherent group included patients whose MPR was below 80%. A MPR of 80% is frequently used as a threshold for adherence to therapyCitation6,Citation12,Citation13.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were conducted using SAS, version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Analyses were conducted in three steps. First, pre-index and patient-level variables were summarized and descriptive tables were generated. Categorical variables were summarized using frequencies and proportions; continuous measures were summarized with means and standard deviations. Second, logistic regression was used to develop weights for the propensity of being adherent. Third, a propensity-weighted regression model was used to estimate the average treatment effect on costs in the adherent sample and to assess the statistical significance of this estimate. The purpose of propensity weighting was to create a pseudo-population of non-adherent patients whose baseline characteristics matched those of the adherent patients; this then allowed estimation of treatment effects (adherence versus non-adherence) in the adherent patients to appropriately adjust for differences in baseline characteristics between adherent and non-adherent patients.

Propensity weights

Propensity scores were developed using a non-parsimonious logistic regression modelCitation14. The resulting propensity score was the probability of being adherent, conditioned on each subject’s pre-treatment variables. These variables included: age, index year, gender, insurance type, Medicare status, smoking status, comorbidity summary measures, indicators for general and specific comorbid conditions, prior drug exposure, prior utilization, and prior costs. Graphs of propensity score logits by adherence group were used to check for overlap of the propensity score distributions (i.e., identification of the region of common support). Sensitivity analyses were performed by removing patients where there was not sufficient overlap between the distribution of scores between the adherent and non-adherent groups.

The probabilities (p) generated in the logistic regression were converted to weights: 1 for adherent patients and p/(1 − p) for non-adherent patients. Weighted analyses were used to test for average treatment effects in the treated (ATT) in the outcome modelsCitation15–18.

Outcomes model

Mean costs for the adherent and non-adherent groups were estimated with propensity-weighted generalized linear models with robust variance estimation and a log link and gamma distribution. Because zero costs were possible and this distribution choice would cause patients with zero amounts to be dropped from the model, a nominal amount was added to all claim costs to ensure retention of the entire sample. Two-sided statistical tests were conducted at the 5% significance level.

Results

Sample attrition

Sample attrition is summarized by diagnosis in . Of the 39,593 patients in the MarketScan database with a HCPCS code for an infliximab infusion on at least one claim between 2006 and 2009, there were 8016 patients who had two or more claims with ICD-9-CM codes for Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis. Common reasons for removal of patients from the study sample were incomplete enrollment in the health plan or pharmacy plan throughout the 360 day pre-index period and 360 day post-index period, and use of another biologic (adalimumab or certolizumab) at any time in the study period (). After removal of subjects who did not satisfy the eligibility criteria, a total of 1646 patients with inflammatory bowel disease (945 Crohn’s disease, 701 ulcerative colitis) were included in the analysis.

Table 2. Sample attrition by diagnosis.

Baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics at the time of the index claim or during the 360 day pre-index period are summarized in . For all patients combined, 51.7% were male and mean ± SD age was 44.4 ± 15.6 years. Index dates of the first infliximab claim were evenly distributed across the four years (2006, 2007, 2008, and 2009). The most common health plans were a preferred provider organization (53.2%), a health maintenance organization (17.1%), or Medicare (11.4%).

Table 3. Patient demographics.

In the 360 day pre-index period, patients had received a mean ± SD of 32.4 ± 24.3 prescriptions. The proportion of pre-index days covered by disease-related drugs was greatest for aminosalicylates (mean ± SD, 38.2 ± 32.8). The mean ± SD total cost of care in the pre-index period was $22,463 ± $25,376 and the mean ± SD total disease-related cost was $11,004 ± $17,978. Inpatient and outpatient costs were the leading contributors to total costs in the pre-index period.

Infliximab adherence

summarizes the baseline characteristics of the study population by infliximab adherence group. Mean age at the index date was 43.1 years for adherent patients and 45.3 years for non-adherent patients. In the adherent and non-adherent groups, respectively, 30.4% and 21.5% of patients received their first dose of infliximab in 2009, and 8.8% and 13.3% of patients had Medicare coverage. During the pre-index period, aminosalicylates were available for 41.7% of days in the adherent group and 35.7% of days in the non-adherent group. Total costs during the pre-index period were $18,358 for adherent patients and $25,310 for non-adherent patients, and outpatient costs during the pre-index period were $7121 and $12,443, respectively.

Propensity weights

Significant (p ≤ 0.100) variables in the logistic model used to obtain propensity scores () were age, infliximab initiation in 2009, Medicare coverage, supplementary diagnoses, office for infliximab initiation, prior aminosalicylate use, prior outpatient costs, number of prior outpatient visits, and number of prior colonoscopies.

Table 4. Significant variables in the logistic regression model used to develop propensity weights.

All-cause healthcare costs

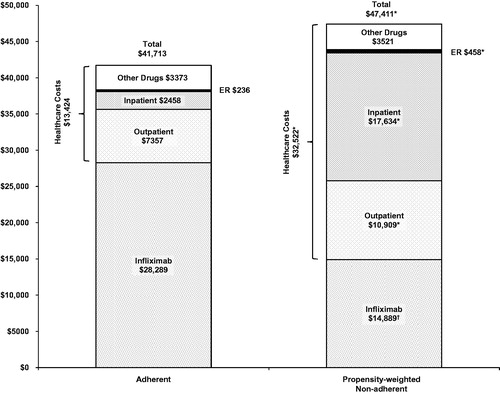

Total costs () were significantly lower in the adherent group than in the propensity-weighted non-adherent group ($41,713 versus $47,411; p < 0.001), with a cost difference of $5698. Annual infliximab drug costs were significantly higher in the adherent group than in the propensity-weighted non-adherent group ($28,289 versus $14,889; p < 0.001). With infliximab drug costs removed, the adherent group had substantially lower healthcare costs than the propensity-weighted non-adherent group ($13,424 versus $32,522; p < 0.001).

Figure 1. Propensity-weighted mean annual all-cause healthcare costs by adherence status. ER, emergency room. *Cost component was significantly higher (p < 0.001) in the propensity-weighted non-adherent group. †Cost component was significantly higher (p < 0.001) in the adherent group.

Among the cost components the main contributor to the difference in healthcare costs between the adherent and propensity-weighted non-adherent groups was the cost of inpatient hospitalization ($2458 versus $17,634; p < 0.001). Outpatient costs ($7357 versus $10,909; p < 0.001) and emergency room costs ($236 versus $458; p < 0.001) were also significantly lower in the adherent group than in the propensity-weighted non-adherent group. Pharmaceutical cost differences between the adherent and propensity-weighted non-adherent group were not statistically significant ($3373 versus $3521; p = 0.460).

Disease-related costs

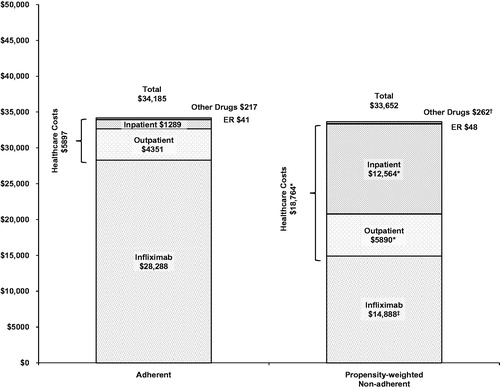

Total disease-related costs () were not significantly different between the adherent and propensity-weighted non-adherent groups ($34,185 versus $33,652; p = 0.633), but after removing infliximab drug costs ($28,288 versus $14,888; p < 0.001) disease-related healthcare costs were significantly lower in the adherent group than in the propensity-weighted non-adherent group ($5897 versus $18,764; p < 0.001). Mean disease-related component costs in the adherent and propensity-weighted non-adherent groups () were $1289 versus $12,564 (p < 0.001) for hospitalizations, $4351 versus $5890 (p < 0.001) for outpatient visits, $217 versus $262 (p < 0.050) for pharmaceuticals, and $41 versus $48 (p = 0.159) for emergency room visits.

Figure 2. Propensity-weighted mean annual disease-related healthcare costs by adherence status. ER, emergency room. *Cost component was significantly higher (p < 0.001) in the propensity-weighted non-adherent group. †Cost component was significantly higher (p < 0.05) in the propensity-weighted non-adherent group. ‡Cost component was significantly higher (p < 0.001) in the adherent group.

Discussion

In this study of 1646 patients with Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis who started infliximab treatment between 2006 and 2009 adherence to infliximab treatment was associated with significantly lower total all-cause healthcare costs in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Total cost in the adherent group was approximately 10% less than it would have been if these patients were non-adherent. After the infliximab drug cost was removed, healthcare costs were approximately 60% lower and disease-related healthcare costs were nearly 70% lower in the adherent group compared to what they would have been if these patients were non-adherent.

A few previous publications have evaluated the costs of non-adherence to infliximab treatment. In an analysis of 638 patients with Crohn’s disease who started infliximab treatment, adherent patients (seven to nine doses in the first year) had significantly lower costs of hospitalization compared with non-adherent patients (four to six doses), with median costs of $9352 and $28,864, respectivelyCitation8. A key limitation of the study was the restriction of the population to patients who received at least four doses, but no more than nine doses, of infliximab in the first yearCitation8. A subsequent study of 448 patients with Crohn’s disease used MPR ≥80% versus MPR <80% as a continuous measure of infliximab adherence, but restricted the analysis to patients who received maintenance treatment, defined as at least one infliximab dose at least 56 days after the index dateCitation9. Mean hospital costs were significantly lower among adherent patients than non-adherent patients ($13,704 versus $40,822)Citation9. A similar analysis of 354 patients with ulcerative colitis who received maintenance infliximab treatment (at least 56 days) reported that infliximab adherence was associated with significantly lower mean costs for ulcerative colitis-related hospitalizations ($423 for MPR ≥80% versus $6678 for MPR <80%)Citation10. Importantly, patients who received maintenance treatment were reported to have significantly lower costs of hospitalization ($14,243 versus $32,745 for patients without maintenance treatment) in that studyCitation10. Each of these studies only reported hospitalization costs; a separate study of 571 patients with Crohn’s disease determined that infliximab adherence (more than seven doses in the first year) was associated with 81% lower total healthcare costs than non-adherence (four to seven doses), with mean values of $8915 and $16,129 after removing the cost of infliximabCitation11. Like the other studies, that study analyzed patients who received at least four doses of infliximabCitation11.

The study reported here did not specify a minimum or maximum number of doses of infliximab a patient could receive in the first year, nor did it restrict the analysis to patients who received maintenance treatment. In accordance with the dosing schedule that is recommended for infliximab induction therapy, the MPR was calculated with the assumption that duration of action was 14 days for the first infusion, 28 days for the second infusion, and 56 days for all subsequent infusions. Additionally, patients with treatment gaps between doses (at least 30, 60, or 90 days after the first, second, and subsequent doses, respectively) were assumed to have restarted induction therapy after the treatment gap. A sensitivity analysis that removed the assumption about restarting induction therapy determined that it did not have a substantial influence on the study findings.

In addition to costs of hospitalization, other costs (outpatient, ER, pharmaceuticals) were included in this study. As in the previous studies, the cost of hospitalization (all-cause and disease-related) was significantly lower among adherent patients, but the other costs were lower as well. Collectively, these methods should have greater applicability for payers who are trying to estimate total costs among patients with inflammatory bowel disease who are adherent or non-adherent to infliximab treatment.

A key distinction of this study was the use of propensity-weighted models to analyze costs. Prior published analyses did not control for potential imbalances between adherent and non-adherent cohorts that could have explained differences in outcomes. The propensity weighting approach used in this analysis was based on a standardized mortality ratio approach that has been suggested as providing more robust, stable, and consistent odds-ratio estimates under conditions of non-uniform treatment effectsCitation16,Citation19. Given the relatively small and similar sample sizes within the groups, this approach allowed inclusion of all patients, unlike traditional propensity matching. It also allowed the treatment effect (adherence versus non-adherence) on costs in adherent patients to be estimated from (1) average costs in the adherent patients and (2) average costs that adherent patients would have been expected to incur if they were non-adherent. The latter costs were estimated by the average costs among the non-adherent patients, standardized to the distribution of baseline characteristics among the adherent patients.

Different definitions for adherence can lead to different estimates of adherence rates. When infliximab is administered according to the recommended dosing scheduleCitation5, patients with Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis receive eight doses in the first year (at 0, 2, 6, 14, 22, 30, 38, and 46 weeks). An MPR of 80% is a standard cutoff value for adherenceCitation6,Citation12,Citation13 and corresponds to slightly fewer than seven doses of infliximab; thus, a patient who received seven or more doses in the 360 day post-index period would satisfy the study criterion for adherence. Previous studies have reported similar levels of persistence to infliximab treatment among patients with inflammatory bowel disease. In an analysis of 1439 patients with Crohn’s disease who received the first three infusions of infliximab, the mean treatment duration was 7.0 doses and 828 (58%) received fewer than seven dosesCitation7.

A potential limitation of this study was the use of retrospective outpatient and hospital administrative claims data, but this is a common approach to cost analysis and provides a larger and more heterogeneous sample than a prospective study. The study relied on medical coding to identify patients with a diagnosis of Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis. To address this limitation, patients were required to have two or more ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes for Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis. Administration of more infliximab doses in the adherent group was probably associated with higher administration costs than in the non-adherent group. However, infliximab administration costs were captured in the healthcare costs (outpatient, inpatient), not in the infliximab costs. Without the higher cost of infliximab administration in the adherent group, the healthcare costs among adherent patients would have been even lower and the actual difference between groups in healthcare costs would have been greater than were reported in this analysis. Costs associated with adverse events were not determined in this study. Disease-related costs were identified from inpatient, outpatient, or emergency room claims with a primary diagnosis of Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis. Some of these costs may have been attributable to a secondary condition, whereas other claims with inflammatory bowel disease in a secondary position that were not included in the subset analysis may have had costs associated with the management of inflammatory bowel disease. Pharmacy claims for other pharmaceuticals used in the management of inflammatory bowel disease were assumed to be disease-related, but they may have been used for other conditions, or patients could have received other pharmaceuticals not indicated for use in inflammatory bowel disease to manage disease-related symptoms. The study did not evaluate the influence of non-adherence on the indirect costs (e.g., time lost from work) of inflammatory bowel disease, which approach $250 million annually in the United StatesCitation20. However, the direct costs of inflammatory bowel disease in the United States are substantially greater than the indirect costsCitation3,Citation4,Citation21. The MPR was used as a continuous measure of adherence, and is a standard approach to evaluate adherence; use of other definitions of adherence (e.g., a minimum number of infliximab doses in the first year) could lead to different findings. A causal relationship between non-adherence and costs cannot be established from this analysis. Lastly, reasons for non-adherence to infliximab treatment are not available from claims data. Thus, it was not possible in this analysis to determine why some patients were adherent to infliximab therapy and others were not. Patients who discontinue infliximab because of tolerability issues, lack of efficacy, or disease complications may have greater hospital costs and appear to be non-adherent. Since the database does not contain reason for discontinuation this possibility was not investigated. However, it is expected that this would represent a small proportion of patients that were hospitalized.

Conclusions

Adherence to infliximab treatment was associated with significantly lower total all-cause healthcare costs in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Contributors to the observed difference included lower mean healthcare costs (hospitalization, outpatient, and ER) among adherent patients than what would have been expected if these patients were non-adherent. Reductions in total healthcare costs among adherent patients have the potential to offset costs associated with infliximab therapy, thereby supporting the overall value of infliximab adherence in inflammatory bowel disease.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

Janssen Scientific Affairs LLC supported this work.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

In the United States, infliximab is marketed by Janssen Biotech Inc., which is a member of the Johnson & Johnson family of companies. G.J.W. and W.H.O. have disclosed that they are stockholders of Johnson & Johnson and are employed by other companies within Johnson & Johnson. G.J.W. was employed by Janssen Scientific Affairs when the study was conducted and then by Janssen Global Services when the paper was being developed. C.M.K. and T.L.S. have disclosed that they have received a research grant from Janssen Scientific Affairs (a Johnson & Johnson company) to conduct this work. B.G.F. has disclosed that he has received research grants from, has been a consultant to, and has participated on a Speakers Bureau for companies within Johnson & Johnson.

JME peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgments

PharmaScribe LLC received financial support from Janssen Scientific Affairs LLC to assist the authors with the preparation and submission of the manuscript. The authors thank Jennifer H. Lofland for her critical review of the draft manuscript.

Previous presentations: Manuscript presented in part as a poster presentation at the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research Annual Meeting (ISPOR), 2–6 June 2012, Washington, DC, USA, and an encore poster presentation at Canadian Digestive Diseases Week (CDDW), 1–4 March 2013, Victoria, British Columbia, Canada.

References

- Abraham C, Cho JH. Inflammatory bowel disease. N Engl J Med 2009;361:2066-78

- Kappelman MD, Moore KR, Allen JK, et al. Recent trends in the prevalence of Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis in a commercially insured US population. Dig Dis Sci 2013;58:519-25

- Yu AP, Cabanilla LA, Wu EQ, et al. The costs of Crohn's disease in the United States and other Western countries: a systematic review. Curr Med Res Opin 2008;24:319-28

- Cohen RD, Yu AP, Wu EQ, et al. Systematic review: the costs of ulcerative colitis in Western countries. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2010;31:693-707

- Remicade (infliximab) Prescribing Information. Horsham, PA: Janssen Biotech, Inc., Revised November 2013

- Lopez A, Billioud V, Peyrin-Biroulet C, et al. Adherence to anti-TNF therapy in inflammatory bowel diseases: a systematic review. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2013;19:1528-33

- Bailey RA, Waters HC, Ernst FR, et al. Infliximab dosing and administration patterns in patients with Crohn's disease in a hospital outpatient setting. Am J Pharm Benefits 2011;3:e121-6

- Carter CT, Waters HC, Smith DB. Impact of infliximab adherence on Crohn's disease-related healthcare utilization and inpatient costs. Adv Ther 2011;28:671-83

- Carter CT, Waters HC, Smith DB. Effect of a continuous measure of adherence with infliximab maintenance treatment on inpatient outcomes in Crohn's disease. Patient Prefer Adherence 2012;6:417-26

- Carter CT, Leher H, Smith P, et al. Impact of persistence with infliximab on hospitalizations in ulcerative colitis. Am J Manag Care 2011;17:385-92

- Kane SV, Chao J, Mulani PM. Adherence to infliximab maintenance therapy and health care utilization and costs by Crohn's disease patients. Adv Ther 2009;26:936-46

- DiMatteo MR. Variations in patients' adherence to medical recommendations: a quantitative review of 50 years of research. Med Care 2004;42:200-9

- DiMatteo MR, Giordani PJ, Lepper HS, et al. Patient adherence and medical treatment outcomes: a meta-analysis. Med Care 2002;40:794-811

- Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika 1983;70:41-55

- Lunceford JK, Davidian M. Stratification and weighting via the propensity score in estimation of causal treatment effects: a comparative study. Stat Med 2004;23:2937-60

- Kurth T, Walker AM, Glynn RJ, et al. Results of multivariable logistic regression, propensity matching, propensity adjustment, and propensity-based weighting under conditions of nonuniform effect. Am J Epidemiol 2006;163:262-70

- Hirano K, Imbens GW. Estimation of causal effects using propensity score weighting: an application to data on right heart catheterization. Health Serv Outcomes Res Methodol 2001;2:259-78

- Curtis LH, Hammill BG, Eisenstein EL, et al. Using inverse probability-weighted estimators in comparative effectiveness analyses with observational databases. Med Care 2007;45:S103-7

- Sturmer T, Rothman KJ, Glynn RJ. Insights into different results from different causal contrasts in the presence of effect-measure modification. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2006;15:698-709

- Gunnarsson C, Chen J, Rizzo JA, et al. The employee absenteeism costs of inflammatory bowel disease: evidence from US National Survey Data. J Occup Environ Med 2013;55:393-401

- Gunnarsson C, Chen J, Rizzo JA, et al. Direct health care insurer and out-of-pocket expenditures of inflammatory bowel disease: evidence from a US national survey. Dig Dis Sci 2012;57:3080-91