Abstract

Objective:

To carry out a cost–utility analysis comparing initial treatment of patients with overactive bladder (OAB) with solifenacin 5 mg/day versus either trospium 20 mg twice a day or trospium 60 mg/day from the perspective of the German National Health Service.

Methods:

A decision analytic model with a 3 month cycle was developed to follow a cohort of OAB patients treated with either solifenacin or trospium during a 1 year period. Costs and utilities were accumulated as patients transitioned through the four cycles in the model. Some of the solifenacin patients were titrated from 5 mg to 10 mg/day at 3 months. Utility values were obtained from the published literature and pad use was based on a US resource utilization study. Adherence rates for individual treatments were derived from a United Kingdom general practitioner database review. The change in the mean number of urgency urinary incontinence episodes/day from after 12 weeks was the main outcome measure. Baseline effectiveness values for solifenacin and trospium were calculated using the Poisson distribution. Patients who failed second-line therapy were referred to a specialist visit. Results were expressed in terms of incremental cost–utility ratios.

Results:

Total annual costs for solifenacin, trospium 20 mg and trospium 60 mg were €970.01, €860.05 and €875.05 respectively. Drug use represented 43%, 28% and 29% of total costs and pad use varied between 45% and 57%. Differences between cumulative utilities were small but favored solifenacin (0.6857 vs. 0.6802 to 0.6800). The baseline incremental cost–effectiveness ratio ranged from €16,657 to €19,893 per QALY.

Limitations:

The difference in cumulative utility favoring solifenacin was small (0.0055–0.0057 QALYs). A small absolute change in the cumulative utilities can have a marked impact on the overall incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) and care should be taken when interpreting the results.

Conclusion:

Solifenacin would appear to be cost-effective with an ICER of no more than €20,000/QALY. However, small differences in utility between the alternatives means that the results are sensitive to adjustments in the values of the assigned utilities, effectiveness and discontinuation rates.

Introduction

The International Continence Society defines overactive bladder as “urgency with or without urge incontinence, usually with increased daytime frequency and nocturia”Citation1. It is a common and significant chronic condition faced by the health care community worldwide with an age-dependent incidenceCitation2,Citation3.

Overactive bladder (OAB) imposes a substantial economic burden on the German health care systemCitation4. According to Klotz et al., a total of 6.48 million adults ≥40 years of age in Germany are affected by OAB, 2.18 million of these individuals experience incontinence and 0.53 million have urge urinary incontinence (UUI)Citation4. Direct OAB-related costs per year were €3.98 billion (nursing care accounts for €1.80 billion of total costs [45%], devices account for €0.68 billion [17%], physician visits account for €0.65 billion [16%], complications account for €0.75 billion [19%], and medication accounts for €0.08 billion [2%]). Direct annual costs are comparable to those of other chronic diseases such as dementia or diabetes mellitus (total annual social insurance expenditures for diabetes mellitus and dementia are €5.1 billion and €5.6 billion, respectivelyCitation4,Citation5.

Given the burden of OAB, various management options are available. The main treatment for OAB is a combination of behavioral measures and antimuscarinic drug therapyCitation6. Antimuscarinics inhibit the effects of acetylcholine at post-junctional muscarinic receptors on detrusor muscle cells, as well as on other structures in the bladder wall, such as the urotheliumCitation7,Citation8. The use of anticholinergic drugs by people with OAB results in statistically significant improvements in symptoms; however, long-term adherence with therapy is limited due to adverse effects, most commonly dry mouthCitation9. Wagg et al. analyzed prescription data for patients receiving these drugs for treatment of the OAB syndrome over a 12 month periodCitation10. At 12 months, they found that the proportions of patients still on their original treatment were: solifenacin 35%, tolterodine extended-release 28%, propiverine 27%, oxybutynin extended-release 26%, trospium 26%, tolterodine immediate-release 24%, oxybutynin immediate-release 22%, darifenacin 17%, and flavoxate 14%.

Solifenacin is an antimuscarinic that has been shown in both short and long term clinical trials to effectively relieve OAB symptoms, is available as a once daily formulation and can be easily titratedCitation6. Recent studies of long-term treatment of OAB with trospium, the most widely used antimuscarinic in Germany, have shown that it is effective and well toleratedCitation11–13.

A number of economic evaluations have been carried out comparing various antimuscarinicsCitation14–17. However, studies comparing the cost-effectiveness of solifenacin vs. trospium chloride are limitedCitation18 and to the authors’ knowledge, no study exists comparing solifenacin vs. trospium chloride from the perspective of the German health care system.

In Germany agencies such as the Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care are responsible for establishing the effectiveness and/or cost-effectiveness of new medicines. Although the German Efficiency Frontier approach to establishing cost-effectiveness differs from approaches utilized in other EU member statesCitation19 (for example, the threshold for demonstrating cost-effectiveness is less explicit and less visible) as in all developed nations there is a need of balancing limited health care resources against the requirement to ensure comprehensive and equitable public access to new technologies.

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of solifenacin vs. trospium chloride using effectiveness and quality of life data from the international literature, resource utilization with assigned local costs from the perspective of the German third-party payers.

Methods

Economic model

An economic model was developed in Microsoft Excel using a 1 year time horizon from the payer perspective. In the model, only direct costs to the payers for medication and other resources were included. The model was divided into four equal periods of three-monthly cycles. A cycle length of 3 months was adopted since it was equivalent to the duration of the clinical trials which formed the basis of the effectiveness data used in the model.

Patients initiate treatment with either solifenacin 5 mg/day, trospium 20 mg twice daily or trospium 60 mg/day. Patients adhere to or discontinue treatment. If symptoms are not adequately controlled at 3 months (complete response) patients will switch to the next treatment option: a higher dose in the case of solifenacin (10 mg/day) or the same dose in case of trospium.

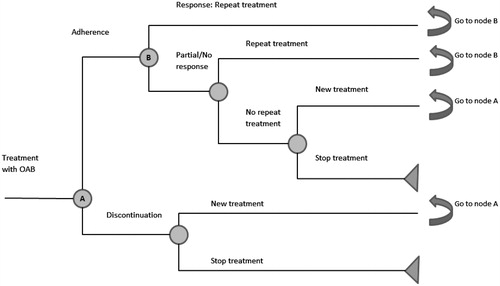

Patients who completely adhere to treatment continue with the same treatment or switch (for incomplete response) (in the case of solifenacin 5 mg/day to 10 mg/day, in case of trospium 40/60 mg/day another cycle of trospium 40/60 mg/day) or stop. Failure after switching or remaining on therapy (second-line therapy) leads to the termination of treatment. This allows two chances at treatment response. The model is represented graphically in .

Outcomes

In this model, UUI was used as the efficacy measure since this was one of the two primary endpoints used in the trospium 60 mg/day trialCitation20. A baseline UUI was calculated based on all included trials. The percentage reduction in UUI from baseline at 3 months was calculated for each trial. The expected amount of UUI at 3 months for solifenacin 5 mg/day, solifenacin 10 mg/day, trospium 40 mg/day or trospium 60 mg/day was calculated using the Poisson distribution; this is an approach that has been used in previous OAB cost-effectiveness studiesCitation21. The Poisson distribution was applied to the derived means to calculate the percentage of patients with a complete response at 3 months.

Following a review of the literature, the key papers that were considered for use in this analysis are summarized in . Five studies (Dmochowski et al.Citation20, Cardozo et al.Citation22, Chapple et al.Citation23, Yamaguchi et al.Citation24, and Zinner et al.Citation25) presented data for improvements in symptoms of urge incontinence, with significant advantages compared to placebo in solifenacin 5 and 10 mg groups, as well as the trospium chloride extended release 60 mg formulation group.

Table 1. Summary of studies used for effectiveness measure in the study.

Comparing solifenacin 5 mg and 10 mg with trospium 60 mg, we found no statistical differences between the two for the following characteristics (risk ratios [95% CI]): Discontinuations due to adverse events 0.61 (0.24, 1.58) and 0.71 (0.27, 1.89) respectively for solifenacin 5 and 10 mg versus trospium 60 mg extended release. Similarly for dry mouth, the results were 1.05 (0.54, 2.04) and 1.80 (0.82, 3.94) for solifenacin 5 mg and solifenacin 10 mg versus trospium 60 mg. Constipation follows a similar pattern to the other outcomes, with 0.52 (0.18, 1.47) and 0.79 (0.25, 2.52) respectively. There was also no statistically significant difference when the solifenacin groups were compared to the 20 mg trospium group. The results as risk ratios (95% CI) were for solifenacin 5 mg vs. trospium 20 mg and solifenacin 10 mg vs. trospium 20 mg respectively: 0.88 (0.47, 1.67) and 1.04 (0.51, 2.10) for discontinuations due to adverse events; 0.83 (0.54, 1.28) and 1.42 (0.77, 2.60) for dry mouth episodes; and 1.04 (0.58, 1.88) and 1.59 (0.73, 3.46) for constipation episodes.

Persistence data

During each cycle patients may also discontinue treatment. The probabilities of discontinuing were based on a United Kingdom general practitioner database analysisCitation10 where data were extracted from the medical records of more than 1,200,000 registered patients via general practice software, and anonymized prescription data were collated for all eligible patients with documented OAB (n = 4833). Persistence rates were estimated at three-monthly intervals (). From these data it was possible to estimate the conditional three-monthly adherence probabilities.

Table 2. Persistence and conditional probabilities (%).

Resource utilization

Resources used in this study () include the comparator products: solifenacin 5 mg/day, solifenacin 10 mg/day, trospium 40 mg/day and trospium 60 mg/day; incontinence pads: for incontinent and untreated patients; GP visits: for continent, incontinent and untreated patients; outpatient visits when changing treatment and specialist visits after second-line treatment failure.

Table 3. Resources, costs and utilities used in the model.

Unit costs

Direct medical costs were expressed in 2012 euros (€) and taken from German specific sourcesCitation28 where possible ().

Utility values

Utility values for response, partial response and stop treatment/no treatment (0.719, 0.692 and 0.665 respectively) () were derived from previous publicationsCitation21 using the EQ-5D, a non-disease specific health-related quality of life instrument. Values range from 0 to 1. A value of 1 represents perfect health while a value of 0 represents the worst possible health state (death).

Results

Results are expressed in terms of costs per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY). Point estimates of both costs and outcomes were reported individually in addition to the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) which compares the relative cost-effectiveness of solifenacin vs. the trospium alternatives. The resultant ICERs were compared with a threshold value of €50,000/QALY.

Sensitivity analysis

As is normal in this type of analysis, the base case cost-effectiveness results were subjected to both one-way deterministic and probability sensitivity analysis (PSA). For the PSA, 1000 Monte Carlo simulations were run, simultaneously changing the values of key variables. The results were in turn used to generate a cost-effectiveness acceptability curve over a range of willingness to pay values in the German setting.

Results

Base case analysis

The daily cost of trospium is considerably cheaper than solifenacin () and clearly the total costs associated with trospium are lower (). However, the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER), incremental cost per QALY (solifenacin vs. trospium) falls within the range of values that may be considered to be cost-effective (30,000–50,000 euros/QALY) in GermanyCitation29. Although, as mentioned previously, under the Efficiency Frontier, the threshold for demonstrating cost-effectiveness is less explicit and less visible than in other European countriesCitation19.

Table 4. Base case results.

Sensitivity analysis – deterministic

In the univariate sensitivity analysis, the values of key variables were varied individually within a realistic range. Drug costs were not varied as they were assumed not to be subject to uncertainty. The results are presented in . The probabilities of continence were the most sensitive variables. However, the results still indicate that solifenacin falls within the cost-effectiveness threshold.

Table 5. Results of the one-way deterministic sensitivity analyses.

Results of the PSA

Results of the PSA for different thresholds are presented in . When the values of key variables are varied randomly and simultaneously with PSA the ICER in most cases is below the minimum threshold of €30,000/QALY.

Table 6. Results of the PSA.

Discussion

Current OAB therapy consists primarily of anticholinergic drugs such as oxybutynin, which are associated with therapy-limiting adverse effects. Hence there is a need for treatments with fewer side effects and greater long-term persistence levelsCitation13.

In this study we have shown in an economic evaluation of commonly used OAB therapies in Germany that solifenacin appears to be cost-effective when compared with trospium. The daily cost of solifenacin is greater, but with a greater effectiveness and a superior long-term persistenceCitation10 the additional overall cost associated with solifenacin may still be considered to represent good value for money by German sickness funds.

Care has to be taken when interpreting the results of economic modeling as no explicit cost-effectiveness acceptability threshold exists in Germany to determine whether a health care intervention is cost-effective, and good use of resources, versus one that is regarded as representing poor value for money. There is still no definite consensus on an acceptable threshold of cost–effectiveness ratio and how much society is willing to pay for health improvements. However, in the USA, $50,000 per QALY is a threshold commonly used to define cost-effectivenessCitation29. Cost-effectiveness thresholds for interventions in England and Wales National Health Service are estimated by NICE to be ∼£30,000 per additional QALYCitation30 for what is acceptable to society. An ICER <€50,000 per QALY has been cited in the recent rheumatology literature in relation to biologic therapy for RACitation31, and recently a theoretical cost-effectiveness threshold of €60,000/QALY has been suggested in the literature for Germany to represent a cost-effective treatmentCitation29. If €40,000/QALY is taken as a hypothetical ceiling threshold, all of our analyses () are within this value (from the payer perspective). Additionally, it should be noted that Nord et al.Citation32 recently raised the question as to whether one single method of valuation (e.g. direct) is indeed sufficient to inform priority setting in different contexts when valuing and comparing interventions and treatment programs for people with different degrees of severity of illness and different potentials for health. The result of the ICER provides an additional factor to help decision makers make rational choices as they have to contend with allocating health care resources in a context of scarcity.

There are few other published economic evaluations comparing solifenacin vs. trospium. One such study by Ko et al.Citation18, although not comparable with the methodology used in the present study (the time frame for the model was 3 months), did show that solifenacin dominated trospium (i.e. was more effective and less costly). A more recent study by Cardozo et al.Citation28 compared the cost-effectiveness of solifenacin against multiple antimuscarinics although trospium was not among the comparators. Solifenacin was dominant in some cases, cost-effective in others (below the £30,000/QALY threshold) and not cost-effective against oxybutynin. However, it should be stated that, in most of the OAB economic evaluations carried out during the last few years, overall differences in QALYs between comparators is minimal. This is for two main reasons: the small differences in utility values between the different health states used in the models and the relatively short time horizon of the evaluations (usually 1 year) which does not permit significant differences to accumulate between comparators. A consequence of these small differences is that the ICERs may be very sensitive to small changes in the value of variables hence the results need to be interpreted with caution.

There are some limitations to this study. It has been necessary to extract data from various sources including different clinical trials, non-German databases and resource utilization data from distinct publications. These data have been combined in an economic model in order to estimate the cost-effectiveness of solifenacin vs. trospium. Ideally, clinical and economic data would be obtained from a randomized clinical trial over a period greater than 3 months with the prospective collection of resource utilization data. Given that this type of information is not currently available it is necessary to make assumptions recognizing that any model will not be a complete reflection of actual clinical practice. However, models do provide a good option for situations where directly comparable clinical and economic data are not available. The current model can be adjusted and updated as additional relevant data becomes available. Likewise while the model focuses on specific products used in Germany it could be adapted to other countries with the input of local costs and taking into consideration local patient management.

Conclusion

In conclusion, in the light of the above considerations, although there are no official threshold values on what constitutes a cost-effective intervention in Germany, treatments are generally considered to be cost-effective if the ICER is no greater than €30,000 per QALY.

Based on this analysis, the ICER comparing solifenacin versus trospium can be considered to be cost-effective.

The daily cost of solifenacin is greater, but with a superior long-term persistence, the additional overall cost associated with solifenacin may still be considered to represent good value for money by German sickness funds.

The difference in cumulative utility favoring solifenacin was small (0.0055–0.0057 QALYs). A small absolute change in the cumulative utilities can have a marked impact on the overall ICERs and care should be taken when interpreting the results.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

EcoStat Consulting UK Ltd was financed by Astellas Pharma Europe Ltd (APEL) to undertake this study.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

W.M.H. has disclosed that he is an employee of EcoStat Consulting UK Ltd. J.N. has disclosed that he is an employee of Astellas Pharma Europe Ltd.

JME peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Professor Axel Olaf Kern (University of Ravensberg) for providing the unit costs used in the analysis.

References

- Abrams P, Artibani W, Cardozo L, et al. Reviewing the ICS 2002 terminology report: the ongoing debate. Neurourol Urodyn 2009;28:287

- Irwin D, Milsom I, Hanskaar S, et al. Population-based survey of urinary incontinence, overactive bladder, and other lower urinary tract symptoms in five countries: results of the EPIC study. Eur Urol 2006;50:1306-14

- Milsom I, Abrams P, Cardozo L, et al. How widespread are the symptoms of overactive bladder and how are they managed? A population-based prevalence study. BJU Int 2001;87:760-6

- Klotz T, Brüggenjürgen B, Burkart M, Resch A. The economic costs of overactive bladder in Germany. Eur Urol 2007;51:1654-63

- Bohm K, Cordes M, Forster T, Krah K. Krankheitskosten 2002. Wiesbaden, Germany: Statistisches Bundesamt, 2004

- Basra R, Kellher C. A review of solifenacin in the treatment of urinary incontinence. Therapeut Clin Risk Manag 2008;4:117-28

- Andersson KE. Muscarinic acetylcholine receptors in the urinary tract. Handb Exp Pharmacol 2011;202:319-44

- Andersson KE. New developments in the management of overactive bladder: focus on mirabegron and onabotulinumtoxinA. Therapeut Clin Risk Manag 2013;9:161-70

- Nabi G, Cody JD, Ellis G, et al. Anticholinergic drugs versus placebo for overactive bladder syndrome in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;4:CD003781

- Wagg A, Compion G, Fahey A, et al. Persistence with prescribed antimuscarinic therapy for overactive bladder: a UK experience. BJU International 2012;11:1-8

- Chapple CR. New once-daily formulation for trospium in overactive bladder. Int J Clin Pract 2010;64:1535-40

- Zinner NR, Dmochowski RR, Staskin DR, et al. Once-daily trospium chloride 60 mg extended-release provides effective, long-term relief of overactive bladder syndrome symptoms. Neurourol Urodyn 2011;30:1214-19

- Biastre K, Burnakis T. Trospium chloride treatment of overactive bladder. Ann Pharmacother 2009;43:283-95

- Speakman M, Khullar V, Mundy A, et al. A cost–utility analysis of once daily solifeancin compared to tolterodine in the treatment of overactive bladder syndrome. Curr Med Res Opin 2008;24:2173-9

- Milsom I, Axelsen S, Kulseng-Hansen S, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of solifenacin flexible dosing in patients with overactive bladder symptoms in four Nordic countries. Acta Obstectricia et Gynecologica 2009;88:693-9

- Noe L, Becker R, Williamson T, et al. A pharmacoeconomic model comparing two long-acting treatments for overactive bladder. J Managed Care Pharm 2002;5:343-52

- Hakkart L, Verboom P, Phillips R, et al. The cost utility of solifenacin in the treatment of overactive bladder. Int Urol Nephrol 2009;41:293-8

- Ko Y, Malone D, Armstrong E. Pharmacoeconomic evaluation of antimuscarinic agents for the treatment of overactive bladder. Pharmacotherapy 2006;26:1694-702

- Klingler C, Shah SMB, Barron AJG, et al. Regulatory space and the contextual mediation of common functional pressures: analyzing the factors that led to the German Efficiency Frontier approach. Health Policy 2013;109:270-80

- Dmochowski RR, Sand PK, Zinner NR, et al. Trospium 60 mg once daily (QD) for overactive bladder syndrome: results from a placebo-controlled interventional study. Urology 2008;71:449-54

- Cardozo L, Thorpe A, Warner J, Sidhu M. The cost-effectiveness of solifenacin vs fesoterodine, oxybutynin immediate-release, propiverine, tolterodine extended-release and tolterodine immediate-release in the treatment of patients with overactive bladder in the UK National Health Service. BJU International 2010;106:506-14

- Cardozo L, Lisec M, Millard R, et al. Randomized, double-blind placebo controlled trial of the once daily antimuscarinic agent solifenacin succinate in patients with overactive bladder. J Urol 2004;172(5 Pt 1):1919-24

- Chapple CR, Rechberger T, Al-Shukri S, et al. Randomized, double-blind placebo- and tolterodine-controlled trial of the once-daily antimuscarinic agent solifenacin in patients with symptomatic overactive bladder. BJU International 2004;93:303-10

- Yamaguchi O, Marui E, Kakizaki H, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo- and propiverine-controlled trial of the once-daily antimuscarinic agent solifenacin in Japanese patients with overactive bladder. BJU International 2007;100:579-87

- Zinner N, Gittelman M, Harris R, et al. Trospium chloride improves overactive bladder symptoms: a multicenter phase III trial. J Urol 2004;171(6 Pt 1):2311-15

- Arlandis-Guzman S, Errando-Smet C, Trocio J, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of antimuscarinics in the treatment of patients with overactive bladder in Spain: a decision-tree model. BMC Urology 2011;11:9-19

- Kobelt G, Jonsson L, Mattiasson A. Cost-effectiveness of new treatments for overactive bladder: the example of tolterodine, a new muscarinic agent: a Markov model. Neurourol Urodynam 1998;17:599-611

- Data from various German sickness funds. Personal communication from Professor Axel Olaf Kern (University of Ravensburg). January 2012

- Neilson A, Sieper J, Deeg M. Cost-effectiveness of etanercept in patients with severe ankylosing spondylitis in Germany. Rheumatology 2010;49:2122-34

- Devlin N, Parkin D. Does NICE have a cost-effectiveness threshold and what other factors influence its decisions? A binary choice analysis. Health Econ 2004;13:437-52

- Merkesdal S, Kirchhoff T, Wolka D, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of rituximab treatment in patients in Germany with rheumatoid arthritis and etanercept failure. Eur J Health Econ 2010;11:95-104

- Nord E, Daniels N, Kamlet M. QALYs: some challenges. Value Health 2009;12(Suppl 1):S10-15