Abstract

Objective:

To characterize patient and physician satisfaction with current standard-of-care botulinum toxin treatment regimens for symptom control in patients with post-stroke spasticity using structured interviews with patients and physicians.

Research design and methods:

Two cross-sectional surveys were conducted in Canada, France, Germany, and the US. The patient survey included patients with post-stroke spasticity who had undergone at least two botulinum toxin A injection cycles. Information on patients’ current and prior botulinum toxin treatment cycles and quality of life was collected. The physician survey included physicians treating post-stroke spasticity with botulinum toxins and collected information regarding physician satisfaction with botulinum toxin treatment for post-stroke spasticity.

Results:

Of 79 participating patients with post-stroke spasticity, 61 (77%) received treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA, 15 (19%) with abobotulinumtoxinA, and three (4%) with incobotulinumtoxinA. Overall, 40.5% of patients were very satisfied, 48.1% were somewhat satisfied, and 11.4% were not at all satisfied with botulinum toxin treatment. Patient satisfaction was lowest just before injection and highest at the time of peak effect. The mean injection interval was 13.7 (SD = 3.5) weeks; however, 43.4% of patients expressed a preference for intervals of ≤10 weeks. Most of the 105 participating physicians’ were moderately (57.7%) or very (36.5%) satisfied with botulinum toxin treatment. However, physicians estimated that 16.2% of their patients with post-stroke spasticity could benefit from shorter injection intervals, and that 24.6% of patients could benefit from higher doses than those permitted by current country directives.

Study limitations:

Patients’ responses were based on subjective recollections and physicians’ responses were based on general impressions.

Conclusions:

These surveys indicate that patients’ and physicians’ satisfaction with botulinum toxin therapy for post-stroke spasticity is overall very good. However, patients’ satisfaction over the treatment cycle varied with onset, peak, and trough of treatment effects and patients and physicians expressed a need for treatment individualization.

Introduction

Spasticity is characterized by a hypertonic motor dysfunction and is part of the upper motor neuron syndrome (UMNS). UMNS may be caused by a variety of etiologies including cerebral or spinal ischemia, traumatic brain or spinal cord injury, multiple sclerosis, cerebral palsy, and other neurological diseasesCitation1,Citation2. Globally, UMNS is estimated to affect more than 12 million peopleCitation3,Citation4. In 2010, an estimated 16.9 million people worldwide experienced a first-ever stroke, and the overall prevalence of stroke survivors was 33.0 millionCitation5. Prevalence estimates of post-stroke spasticity are highly variable. A recent literature review found that the prevalence of post-stroke spasticity ranged from 4–42.6% of patients who had suffered a stroke, and the prevalence of disabling spasticity was 2–13%. Post-stroke spasticity develops over time and was evident in 4–27% of stroke survivors in the first 1–4 weeks after stroke; in 19–26.7% of post-acute patients (1–3 months post-stroke); and in 17–42.6% of patients in the chronic phase (>3 months post-stroke)Citation6.

Botulinum toxins have been extensively used for the treatment of spasticity. An American Academy of Neurology evidence-based review of the safety and efficacy of botulinum toxin for the treatment of spasticity recommends that botulinum toxin should be offered as a treatment option to reduce muscle tone and improve passive function in adults with spasticity (level A), and should also be considered to improve active function (level B)Citation7,Citation8. European Consensus Statements also recommend botulinum toxin type A as a valuable tool in the multi-modal treatment of adult spasticityCitation9,Citation10. While botulinum toxin is a highly effective treatment for spasticity, treatment effects are temporary and many patients experience partial to complete re-emergence of symptoms towards the end of each injection cycle as the benefits of the previous dose begin to wear off. The current standard of care is injection intervals of 3 months or longerCitation11. This recommendation is largely based on a retrospective patient review by Greene et al.Citation12 from 1994 in patients with cervical dystonia. Importantly, however, the patients described in this study had been treated with the original botulinum toxin formulation (Allergan lot 79-11), which has been reported to be associated with an antibody formation rate of up to 10.5%Citation12. In a subsequent study comparing lot 79-11 with the current onabotulinumtoxinA (Botox), which has a reduced protein load, the number of patients developing resistance was much reduced compared with lot 79-11Citation13. Importantly, an individualized dosing schedule, customized to patients’ symptoms, might improve patient satisfaction during the entire treatment cycle. However, in the absence of long-term data regarding a potential effect of flexible, individualized botulinum toxin treatment intervals, a minimum injection interval of 3 months has today become the standard of care for many patients receiving botulinum toxin treatment. Owing to inflexible dosing schedules, patients may have to tolerate mild-to-severe symptoms towards the end of each treatment cycle before the next injection is administered.

In addition to flexible treatment intervals, individualized dosing is also important for treatment efficacy and satisfaction. Some studies in upper-limb post-stroke spasticity have permitted individualized dosingCitation14–16, while others have notCitation17–25. Doses administered in clinical trials vary widely. In a systematic review, Elia et al.Citation26 report that dose ranges administered to finger flexor muscles in patients with post-stroke spasticity ranged from 7.5–225 U for onabotulinumtoxinA, and from 100–500 U for abobotulinumtoxinA (Dysport). Current dosing guidelines for spasticity in adults give broad dose ranges for onabotulinumtoxinA and recommend a total maximum body dose of 600 U per visitCitation10. To optimize treatment outcomes, physicians need to have the flexibility to administer individualized doses according to patient needs. However, as the use of higher doses has not been systematically evaluated, in many countries the approved maximum doses are lower than doses recommended in current treatment guidelines. Moreover, in most countries, the treatment of lower-limb spasticity is not included in the prescribing information for botulinum toxin formulations.

Structured patient and physician surveys were conducted to characterize treatment satisfaction with the current standard-of-care botulinum toxin type A dosing regimens for the symptomatic control of post-stroke spasticity. The aim was to capture the perspectives of patients affected by post-stroke spasticity and physicians who treat such patients.

Patients and methods

Study design

The survey questionnaire was refined following pilot interviews in Canada, France, and Germany. Structured surveys were carried out in four countries (Canada, France, Germany, and the US) in 2008 (see Supplementary Appendix for survey questionnaire). At this time, onabotulinumtoxinA was approved for the treatment of upper-limb post-stroke spasticity in Europe and Canada and abobotulinumtoxinA was approved for this indication in Europe, but incobotulinumtoxinA (Xeomin) was not approved for the treatment of upper-limb post-stroke spasticity at the time of the survey.

To be included in the patient survey, patients had to have undergone at least two treatment sessions with any formulation of botulinum toxin type A. Patients who had received botulinum toxin injections at less than 10-week intervals were excluded. Patients were asked by their physicians if they were willing to participate and interested patients consented to being contacted by the interviewer.

Information was collected on patient demographics, disease characteristics, and previous treatments with botulinum toxin. Interviews were conducted by medically experienced interviewers and took place 7–10 weeks after patients’ last botulinum toxin treatment.

Physicians were contacted via telephone to enquire if they would like to participate in the survey. To be included, physicians must have had experience in administering botulinum toxin injections for medical purposes for ≥3 years, including experience in injecting botulinum toxin for the treatment of post-stroke spasticity.

Evaluation of treatment

The survey asked patients about their most recent botulinum toxin injection cycle, including general impression of treatment, injection intervals, as well as perceived time of onset of treatment effect, peak effect, and waning of treatment effect. Patients evaluated their satisfaction with therapy at different stages of their latest treatment cycle (current, at peak effect, and right before their last injection) using a visual analog scale (VAS) ranging from 1–10. For the analysis, observed values 1–3 were classed as ‘not at all satisfied’, 4–7 were classed as ‘somewhat satisfied’, and 8–10 were classed as ‘very satisfied’. Patients also stated their preference for a re-injection of botulinum toxin on the day of interview using a VAS ranging from 1–10, where 1–3 was classed as ‘not at all’, 4–7 as ‘somewhat’, and 8–10 as ‘very much’. The questionnaire further asked for the preferred interval length for receiving botulinum toxin injections (in weeks). The survey questionnaire was also used to assess quality of life, based on general subjective ratings of current state of health as well as assessments of the impact of spasticity on specific aspects of patients’ lives. Patients rated their current state of health on a VAS ranging from 0 (worst possible) to 100 (best possible). The use of this subjective scale was intended to ensure that results reflected patients’ own perspectives.

The physician survey assessed physicians’ perspectives on botulinum toxin treatment for patients with post-stroke spasticity. Information collected included treatment intervals, dosing, and satisfaction with botulinum toxin treatment in post-stroke spasticity. Satisfaction was rated using a numeric rating scale ranging from 1–10, where 1–3 was classed as ‘not at all satisfied’, 4–7 as ‘moderately satisfied’, and 8–10 as ‘very satisfied’ for the analysis. In addition, physicians were asked about restrictions to dosing and treatment interval that they encountered in their respective countries. The responses were based on physicians’ own knowledge and interpretation of restrictions; no information was provided by the interviewer to the physicians.

Statistical methodology

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize all survey data collected in this study. For both the physician and patient surveys, percentages presented are based upon non-missing data.

Results

Patient survey

Patients

A total of 79 patients with post-stroke spasticity were interviewed (Germany, n = 35 [44.3%]; France, n = 10 [12.7%]; USA, n = 26 [32.9%]; Canada, n = 8 [10.1%]). Of these, 15 were currently being treated with abobotulinumtoxinA (19%), 61 (77%) with onabotulinumtoxinA, and three (4%) with incobotulinumtoxinA. Demographic and baseline disease-related characteristics are shown in . At the time of the survey, the mean duration of spasticity was 4.1 (SD = 4.0) years and patients had been receiving botulinum toxin type A injections for a mean of 2.0 (SD = 2.3) years. More than half of the patients (59.5%) had co-morbid chronic diseases that required medical management.

Table 1. Patient demographic and baseline disease characteristics (patient survey).

Treatment intervals

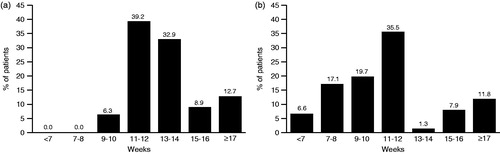

Patients usually received botulinum toxin treatment at intervals of 10 weeks (6.3%), 11–12 weeks (39.2%), 13–14 weeks (32.9%), 15–16 weeks (8.9%), or ≥17 weeks (12.7%) (). The mean injection interval was 13.7 (SD = 3.5) weeks. Patients were asked if they had received an explanation for the reason leading physicians to choose a particular treatment interval and, if so, what the explanation was. Patients who stated that they had received a reason (n = 27, 34.2%) provided the following explanations: ‘you just shouldn’t give it more often’ (n = 9); ‘this injection interval is the most successful’ (n = 5); ‘need to avoid formation of antibodies’ (n = 4); ‘risk of side-effects with shorter intervals’ (n = 4); ‘this is standard procedure’ (n = 3); ‘individual state of the patient’ (n = 1), ‘according to the state of approval’ (n = 1), and ‘according to studies available’ (n = 1). Reasons were not mutually exclusive, i.e., more than one reason may have been provided.

Evaluation of the last injection cycle

When asked, 44 patients were able to recall the onset, peak, and decline of effects of their most recent injection. These patients estimated that the mean time to onset of treatment effect was 8.6 (SD = 6.4) days, that the mean time to peak effect was 3.7 (SD = 2.4) weeks, and that treatment effects declined at a mean of 9.3 (SD = 4.0) weeks.

Evaluation of the current injection cycle

When asked about satisfaction with their current therapy, most patients (88.6%) were at least somewhat satisfied, while 11.4% of patients were not satisfied at all (). When asked about their satisfaction with therapy just before the last injection, 36.4% of patients were not satisfied at all. At the time of peak of therapy effect, the majority of patients were at least somewhat satisfied, but 2.3% were not satisfied at all ().

Table 2. Information regarding current injection cycle (patient survey).

The majority of patients stated that they would prefer to have a re-injection on the day of the interview (7–10 weeks after their most recent injection) if they were given a choice (36.7% somewhat and 36.7% very much). However, when patients were specifically asked about their preference for injection intervals, the median preferred interval was 12 weeks (mean = 12.2; SD = 6.5 weeks). Interestingly, 33 patients (43.4%) said they would prefer injection cycles shorter than 10 weeks ().

Current state of health

Patients’ overall mean rating of their state of health on the day of the interview was 53.2 (SD = 22.0) on a VAS scale ranging from 0 (worst possible state of health) to 100 (best possible state of health).

Physician survey

Physicians

One-hundred and five physicians with experience in treating post-stroke spasticity with botulinum toxin injections were interviewed. Their demographic and professional characteristics are summarized in . The mean time in their current specialty was 15.3 (SD = 7.9) years and their mean experience in using botulinum toxin for medical reasons was 9.2 (SD = 5.3) years. On average, 49.6% (SD = 32.1%) of the physicians’ patients with post-stroke spasticity received treatment with botulinum toxin.

Table 3. Physician demographic and professional characteristics (physician survey).

Satisfaction with botulinum toxin for treating post-stroke spasticity

Most of the 104 physicians who answered this question were either moderately satisfied (57.7%) or very satisfied (36.5%); 5.8% were not at all satisfied.

Treatment of post-stroke spasticity with botulinum toxin

The median treatment interval for post-stroke spasticity was 12 weeks for onabotulinumtoxinA (4–24 weeks), abobotulinumtoxinA (3–24 weeks), and incobotulinum-toxinA (8–14 weeks). In line with product labeling, the median maximum doses physicians used for treating post-stroke spasticity were 400 U for onabotulinumtoxinA (n = 61) and incobotulinumtoxinA (n = 11), and 1500 U for abobotulinumtoxinA (n = 30).

Treatment intervals in post-stroke spasticity

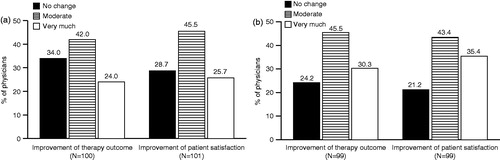

Physicians interviewed felt that, on average, 16.2% (range =0–90%) of patients would benefit from shorter injection intervals than those currently permitted. Physicians stated that lifting current restrictions on treatment intervals would improve botulinum toxin therapy outcomes very much (24.0%), moderately (42.0%), or would not change outcomes (34.0%), and would improve patient satisfaction very much (25.7%), moderately (45.5%), or not at all (28.7%) ().

Figure 2. Impact of shortening treatment intervals (a) and of higher dosing (b), if restrictions could be removed. Physicians were asked if in their opinion there would be an improvement in therapy outcomes and patient satisfaction if restrictions regarding treatment intervals (a) or dosing (b) were removed. Percentages based on non-missing data only.

Maximum dosing in post-stroke spasticity

Physicians interviewed felt that, on average, 24.6% (range =0–100%) of patients would benefit from higher doses than those currently permitted. They further reported that lifting current restrictions on dosing would improve botulinum toxin therapy outcomes very much (30.3%), moderately (45.5%), or not at all (24.2%), and would improve patient satisfaction very much (35.4%), moderately (43.4%), or not at all (21.2%) ().

Discussion

Post-stroke spasticity considerably diminishes health-related quality of life in stroke survivors, affecting physical, social, and emotional domainsCitation27,Citation28. Treatment with botulinum toxin has been found to be well tolerated and effective in this population and may improve quality of lifeCitation15,Citation16,Citation29. These structured patient and physician surveys were conducted to determine the level of satisfaction with botulinum toxin treatment, from the perspectives of both patients with post-stroke spasticity and physicians who treat post-stroke spasticity. Although most patients were generally satisfied with their current therapy at the time of the interview (7–10 weeks after their last injection), only 40.5% were very satisfied; 48.1% of patients were somewhat satisfied and 11.4% were not at all satisfied. The trend of patients’ satisfaction generally followed the onset, peak, and trough of efficacy. However, treatment effects are individual and time to onset, peak, and trough of efficacy varies between patients. Satisfaction was lowest just before the next injection (36.4% not satisfied at all), when the effects of the previous treatment were diminishing, and were highest at the time of peak effect, with 68.2% of patients very satisfied.

While the mean treatment interval was 13.7 (3.5) weeks, nearly half of patients (43.4%) stated that they would prefer a treatment interval of 10 weeks or less. On the other hand, more than one-fifth of patients (21.1%) would prefer to be treated less frequently than what is current practice. The vast majority of physicians interviewed (94.2%) were at least moderately satisfied with botulinum toxin treatment for post-stroke spasticity. However, many felt that the restrictions on treatment intervals and dosing in their respective countries were impeding both treatment outcomes and patient satisfaction. Hence, there is a need for further treatment optimization through individualized dosing and injection intervals. Physicians felt that, on average, 16.2% of their patients would benefit from shorter treatment intervals than those currently permitted and that their patients would benefit in terms of both therapy outcomes and patient satisfaction. However, not all patients will require treatment intervals shorter than the 12-week standard-of-care interval. Indeed, the majority of patients may not need to change their treatment intervals. Whether shorter or longer, it is important that botulinum toxin treatment intervals can be individualized to maximize patient outcomes.

The physician survey results confirm the desire for more flexibility in dosing. The physicians in this survey felt that 24.6% of their patients would gain additional benefit from higher doses of botulinum toxin than those currently permitted and, again, that higher doses would improve both therapy outcomes and patient satisfaction. The use of higher than labeled doses of incobotulinumtoxinA or onabotulinumtoxinA has been reported and recommendedCitation10,Citation30, but clinical data from well-designed, prospective clinical trials are lacking. Moreover, in most countries botulinum toxin treatment is not yet approved for lower-limb post-stroke spasticity. While not all physicians who participated in this survey believed that their patients would benefit from doses higher than those currently permitted in their respective country, higher doses were nonetheless generally desired to maximize patient outcomes.

The patient and physician surveys presented in this study have some clear methodological limitations. Patient responses were based on patients’ subjective recollections. Similarly, physicians’ responses were also based on general impressions rather than more objective data such as chart reviews. Another limitation of the study is the small sample size, which may limit generalization of the results to the total population of patients with post-stroke spasticity treated with botulinum toxin.

A similar cross-sectional survey has previously been conducted in patients with cervical dystonia and reported comparable findings regarding patient satisfaction with botulinum toxin treatmentCitation31. Most patients with cervical dystonia reported that they were satisfied with their current botulinum toxin therapy and, as seen in this survey, patient satisfaction was lowest just before the next injection. Of note, patients with cervical dystonia tend to receive lower doses of botulinum toxin than many patients with spasticity, who may receive treatment for multiple muscle groups.

The duration of treatment effects with botulinum toxin varies from patient to patient. Furthermore, in patients with post-stroke spasticity the duration of treatment effects may also depend on the stage of post-stroke recovery. Most clinical studies involve patients who have stabilized for at least 3–6 months after a stroke rather than patients in the more acute stage of recovery. To improve patients’ treatment satisfaction and optimize treatment outcomes, individualization of the injection interval should be considered. Further studies are required to determine if other conditions treated with repeated botulinum toxin injections, such as blepharospasm, show a similar need for treatment individualization. Ideally, patients should experience only a mild re-emergence of symptoms towards the end of their individualized treatment cycle, and dosing and treatment should be adjusted accordingly. Shorter treatment intervals would likely help to achieve this, provided that they are not associated with an increased risk of side-effects. Further prospective studies are required to fully understand the lifecycle of patients’ satisfaction with botulinum toxin treatment. An individualized treatment would also avoid ‘over-treatment’, since quite a significant number of patients would prefer to be injected less frequently, which would also contribute to improved patient satisfaction in the end.

Conclusions

The results of these surveys indicate that overall patients’ and physicians’ satisfaction with botulinum toxin injections in treating post-stroke spasticity is very good. Throughout the botulinum toxin treatment cycle, patient satisfaction with treatment followed the onset, peak, and trough of treatment efficacy. However, these may vary among the patient population and patients and physicians expressed a need for treatment individualization.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was conceived and sponsored by Merz Pharmaceuticals, GmbH. All authors contributed to the initial drafting of the manuscript, subsequent review and critique, and all authors approved the final draft before submission.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

Djamel Bensmail has received consulting fees or other remuneration (payment) from Allergan, Almirall, Ipsen, Medtronic, and Merz Pharmaceuticals. Angelika Hanschmann is an employee of Merz Pharmaceuticals. Jörg Wissel has received consulting fees and payments for speakers’ bureau from Allergan, Ipsen, Medtronic, and Merz Pharmaceuticals.

Supplementary Appendix 1: Final questionnaire used for the survey of patients with post-stroke spasticity

Download PDF (391.2 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all patients and physicians who participated in the survey and the interviewers who conducted the sessions. The authors would also like to thank Dr. Cindy Ivanhoe (Baylor College of Medicine) for her helpful comments on an earlier draft of the manuscript. Medical writing assistance was provided by Starr L. Grundy, BSc Pharm of SD Scientific, Inc., and Dr. Simone Boldt of Complete Medical Communications, funded by Merz Pharmaceuticals.

Previous presentations: (1) TOXINS 2012: Basic Science and Clinical Aspects of Botulinum and Other Neurotoxins, December 5–8, 2012, Miami Beach, FL, USA; (2) XXI World Congress of Neurology, September 21–26, 2013, Vienna, Austria; and (3) APM&R 2013 Annual Assembly, October 3–6, 2013, National Harbor, MD, USA.

Notes

*Botox is a registered trademark of Allergan Inc.

†Dysport is a registered trademark of Ipsen Biopharm Ltd.

‡Xeomin is a registered trademark of Merz Pharma GmbH & Co. KGaA.

References

- Ozcakir S, Sivrioglu K. Botulinum toxin in poststroke spasticity. Clin Med Res 2007;5:132-8

- Ward AB. Spasticity treatment with botulinum toxins. J Neural Transm 2008;115:607-16

- Vanek ZF, Menkes JH. Spasticity. Medscape. New York, NY: WebMD, 2012. Available at: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1148826-overview#aw2aab6b3 [Last accessed 05 June 2014]

- Brin MF. Preface. Muscle Nerve Suppl 1997;6:S1

- Feigin VL, Forouzanfar MH, Krishnamurthi R, et al. Global and regional burden of stroke during 1990-2010: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2014;383:245-54

- Wissel J, Manack A, Brainin M. Toward an epidemiology of poststroke spasticity. Neurology 2013;80:S13-19

- Esquenazi A, Albanese A, Chancellor MB, et al. Evidence-based review and assessment of botulinum neurotoxin for the treatment of adult spasticity in the upper motor neuron syndrome. Toxicon 2013;67:115-28

- Simpson DM, Gracies JM, Graham HK, et al. Assessment: botulinum neurotoxin for the treatment of spasticity (an evidence-based review): report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 2008;70:1691-8

- Ward AB, Aguilar M, De Beyl Z, et al. Use of botulinum toxin type A in management of adult spasticity–a European consensus statement. J Rehabil Med 2003;35:98-9

- Wissel J, Ward AB, Erztgaard P, et al. European consensus table on the use of botulinum toxin type A in adult spasticity. J Rehabil Med 2009;41:13-25

- Swope D, Barbano R. Treatment recommendations and practical applications of botulinum toxin treatment of cervical dystonia. Neurol Clin 2008;26(1 Suppl):54-65

- Greene P, Fahn S, Diamond B. Development of resistance to botulinum toxin type A in patients with torticollis. Mov Disord 1994;9:213-17

- Jankovic J, Vuong KD, Ahsan J. Comparison of efficacy and immunogenicity of original versus current botulinum toxin in cervical dystonia. Neurology 2003;60:1186-8

- Brashear A, Gordon MF, Elovic E, et al. Intramuscular injection of botulinum toxin for the treatment of wrist and finger spasticity after a stroke. N Engl J Med 2002;347:395-400

- Kaňovský P, Slawek J, Denes Z, et al. Efficacy and safety of botulinum neurotoxin NT 201 in poststroke upper limb spasticity. Clin Neuropharmacol 2009;32:259-65

- Kaňovský P, Slawek J, Denes Z, et al. Efficacy and safety of treatment with incobotulinum toxin A (botulinum neurotoxin type A free from complexing proteins; NT 201) in post-stroke upper limb spasticity. J Rehabil Med 2011;43:486-92

- Bakheit AM, Thilmann AF, Ward AB, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study to compare the efficacy and safety of three doses of botulinum toxin type A (Dysport) with placebo in upper limb spasticity after stroke. Stroke 2000;31:2402-6

- Bakheit AM, Pittock S, Moore AP, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the efficacy and safety of botulinum toxin type A in upper limb spasticity in patients with stroke. Eur J Neurol 2001;8:559-65

- Bhakta BB, Cozens JA, Chamberlain MA, et al. Impact of botulinum toxin type A on disability and carer burden due to arm spasticity after stroke: a randomised double blind placebo controlled trial. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2000;69:217-21

- Brashear A, McAfee AL, Kuhn ER, et al. Botulinum toxin type B in upper-limb poststroke spasticity: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2004;85:705-9

- Childers MK, Brashear A, Jozefczyk P, et al. Dose-dependent response to intramuscular botulinum toxin type A for upper-limb spasticity in patients after a stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2004;85:1063-9

- Hesse S, Reiter F, Konrad M, et al. Botulinum toxin type A and short-term electrical stimulation in the treatment of upper limb flexor spasticity after stroke: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Rehabil 1998;12:381-8

- Pittock SJ, Moore AP, Hardiman O, et al. A double-blind randomised placebo-controlled evaluation of three doses of botulinum toxin type A (Dysport) in the treatment of spastic equinovarus deformity after stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis 2003;15:289-300

- Simpson DM, Alexander DN, O'Brien CF, et al. Botulinum toxin type A in the treatment of upper extremity spasticity: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Neurology 1996;46:1306-10

- Suputtitada A, Suwanwela NC. The lowest effective dose of botulinum A toxin in adult patients with upper limb spasticity. Disabil Rehabil 2005;27:176-84

- Elia AE, Filippini G, Calandrella D, et al. Botulinum neurotoxins for post-stroke spasticity in adults: a systematic review. Mov Disord 2009;24:801-12

- Zorowitz RD, Gillard PJ, Brainin M. Poststroke spasticity: sequelae and burden on stroke survivors and caregivers. Neurology 2013;80:S45-52

- Sturm JW, Donnan GA, Dewey HM, et al. Quality of life after stroke: the North East Melbourne Stroke Incidence Study (NEMESIS). Stroke 2004;35:2340-5

- Elovic E, Brashear A, Kaelin D, et al. The effect of repeated treatment of botulinum toxin type A on poststroke, spasticity-related pain: a subgroup analysis of patients in a 12-month trial. Neurology 2007;68:A177 ABS-P04.131, IN10-1.008 (abstract)

- Dressler D. Routine use of Xeomin in patients previously treated with Botox: long term results. Eur J Neurol 2009;16(2 Suppl):2-5

- Sethi KD, Rodriguez R, Olayinka B. Satisfaction with botulinum toxin treatment: a cross-sectional survey of patients with cervical dystonia. J Med Econ 2012;15:419-23