Abstract

Objective:

The objective for the research was to evaluate the direct healthcare costs for Crohn’s disease (CD) patients categorized by adherence status.

Methods:

Adult patients with ≥1 claim for infliximab and ≥2 claims for CD who were continuously insured for 12 months before and after their first infliximab infusion (index date) were identified in a 2006–2009 US managed care database. Patients were excluded if they had rheumatoid arthritis claims, received infliximab billed as a pharmacy benefit, or received another biologic drug. Patients were categorized as being either adherent or intermittently adherent to infliximab using a pre-defined algorithm. Total and component direct costs, CD-related costs, rates of surgery, and days of hospitalization were estimated for the 360-day post-index period. Propensity weighted generalized linear models were used to adjust the cost estimates for potential confounding variables.

Results:

The total propensity weighted cost for infliximab adherent patients was $40,425 (95% CI = [$38,686, $42,242]), compared to $41,082 (95% CI = [$38,163, $44,223]) for the intermittently adherent (p = 0.71). However, adherent patients had lower total direct medical costs, exclusive of infliximab, that were $13,097 (95% CI = [$12,141, $14,127]) compared with $20,068 (95% CI = [$17,676, $22,784]) for intermittently adherent patients as a result of substantially lower hospital and outpatient costs (p < 0.0001).

Conclusions:

Greater drug-related costs for infliximab adherent patients were offset by lower costs from hospitalization and outpatient visits. These findings indicate that adherent patients have improved clinical outcomes, at a similar aggregate cost, than patients who are only intermittently adherent to therapy.

Introduction

Crohn’s disease (CD) is a chronic, progressive disease of the gastrointestinal tract that is characterized by transmural inflammation. Approximately 500,000 people in the US are affectedCitation1. Initially, most patients have inflammatory CD, with typical symptoms of abdominal pain, diarrhea, and weight lossCitation2. If left uncontrolled, inflammation leads to structural damage and stricturing or penetrating complicationsCitation2. Accordingly, an emerging principle of therapy is that early and complete control of the inflammatory process is necessary to prevent structural damage and preserve normal bowel functionCitation3.

Rapid induction and long-term maintenance of remission are vital therapeutic goals in CD. Patients in remission have decreased incidences of hospitalization and surgery, improved quality-of-life, and increased employment compared to those with active diseaseCitation4. Conventional therapies for CD include corticosteroids, immunosuppressives (thiopurines and methotrexate), and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) antagonistsCitation5. The latter agents are the most effective drugs currently available and are usually prescribed to high risk patients who have the greatest cost of care.

Adherence to treatment is an important clinical consideration for most chronic diseases. A number of studies have previously demonstrated the importance of adherence to TNF antagonists in patients with CDCitation6,Citation7. Non-adherence is associated with reduced treatment efficacy; greater medical service utilization, especially hospitalization; and greater total direct medical costsCitation8–10. Therefore, ensuring adherence to CD treatment, ‘may not only improve the rate of remission achieved by patients with CD, but may also potentially reduce the economic burden of the disease’ (p944)Citation8.

Adherence comparisons of biologic agents used for treatment of CD have typically compared ‘adherent’ and ‘non-adherent’ patients. Adherence, as defined by the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) Work Group, is ‘the extent to which a patient acts in accordance with the prescribed interval and dose of a dosing regimen’ (p46)Citation11. The causes and consequences of non-adherence to TNF antagonist therapy in CD are not completely understood. Potential causes include patient characteristics (e.g., gender, age, educational level), drug properties (e.g., route of administration, dosing frequency, tolerability), and societal issues (e.g., insurance status, drug acquisition cost, access to care). As noted previously, the consequences of non-adherence are primarily reduced efficacy and greater cost; however, a specific concern related to non-adherence with TNF antagonists is the risk of sensitization. Development of anti-drug antibodies (ADAs) is associated with both decreased efficacy and an increased risk of hypersensitivity reactionsCitation12,Citation13. Empiric evidence shows that patients with CD who receive a full course of infliximab induction therapy and continuous maintenance treatment have lower rates of ADAs and better long-term efficacy than those who receive episodic treatmentCitation14.

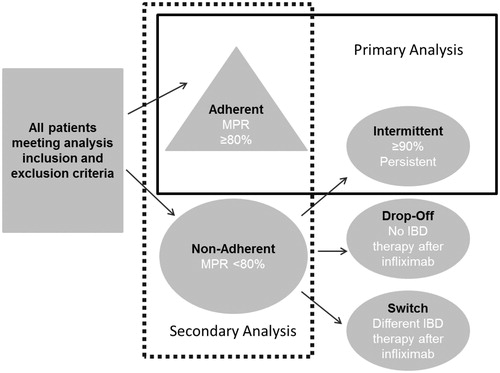

For these reasons, understanding the consequences of non-adherence to TNF antagonists is important from both a clinical and economic perspective. The purpose of this analysis was to compare healthcare costs and utilization for patients who were adherent to infliximab therapy with patients who were intermittently adherent to infliximab therapy. Intermittent adherence was defined as having therapy for a clinically meaningful duration but with missed doses. Typical compliance analyses compare adherent vs non-adherent patients. The use of intermittent adherence is novel because patients who discontinued infliximab or switched to other therapies are excluded from the analysis. Conceptually, patients who discontinued or switched therapy may have tolerability issues or lack of efficacy in distinction to patients who did not return for therapy (i.e., patient choice) or who had lack of follow-up as reasons for non-adherence. The tests for differences between adherent and intermittently adherent patients should provide a more robust test of differences attributable to patient behaviour. The primary hypothesis was that patients who were adherent to infliximab would have lower total direct medical costs than those who were intermittently adherent.

Patients and methods

Data sources

The data for this study are from the Truven Health MarketScan® Commercial and Medicare Research Database, a national managed care claims dataset, from the time period January 1, 2005 through December 31, 2010. The annual medical database includes private sector healthcare data from ∼100 payers with more than 500 million claim records available. These data represent the medical experience of insured employees and their dependents for active employees, early retirees, Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (COBRA) participants, and Medicare-eligible retirees with employer-provided Medicare Supplemental plans. The database is a de-identified, HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996) compliant database and, as such, no institutional review board approval was necessary for these analyses.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Adult patients (≥18 years of age) were included in the analysis if they had one or more claims for infliximab billed with a Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) code of J1745 between January 1, 2006 and December 31, 2009 and met other analysis criteria. The first infliximab date in this time period was the analysis index date. Patients were also required to have two or more claims on different dates in the available data with an International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Edition, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis for Crohn’s disease (555.XX) during a 360-day pre-index period. The requirement of two coding events was used to increase the likelihood that a valid CD diagnosis was present. Patients were required to have continuous enrollment for 12 months before and 12 months after the index date to ensure availability of complete claims. Patients could not have evidence of infliximab use during the 360-day pre-index period. Patients were excluded from the analysis if they had any claim with an ICD-9-CM code for rheumatoid arthritis at any time in the available data, had any claims for infliximab billed as a pharmacy benefit, or had evidence of use of another biologic drug.

Variable and cohort definitions

Adherence to infliximab was based on infusion dates and dosing intervals described in the infliximab package insert. This analysis assumed duration of action of 14 days for the first infusion, 28 days for the second infusion, and 56 days for any subsequent infusions. Calculation of the number of days of therapy received in the post-index period was based on this assumed duration of action. Gaps in therapy that exceeded a pre-specified minimum between infusion dates were assumed to indicate that therapy was re-started. If the time between infusion 1 and 2 exceeded 30 days, then the subsequent infusion had an assumed duration of 14 days and the therapy cycle was assumed to have been re-started. If the time between infusion 2 and 3 exceeded 60 days, then the subsequent infusion had an assumed duration of 14 days and the therapy cycle was assumed to have been re-started. If any of the subsequent infusions had a gap of more than 90 days, then the subsequent infusions had an assumed duration of 14 days and the therapy cycle was assumed to have been re-started. If claims for infusions were closer than the assumed duration of action, only the actual numbers of days between claims were counted. Claims with a duration that extended to the end of the observation period used the end of observation date as the ending date for that event.

Mutually exclusive medication adherence groups were assigned. The adherent group was identified using a medication possession ratio (MPR) that was defined as the number of days in the observation period where infliximab was available based on infusion dates and the durations of action from prescribing information divided by 360 days (i.e., the fixed observation period). MPR was calculated as follows:

Sum of the number of days of therapy based on infusion dates and duration of action from prescribing information/360 days (i.e., the duration of the observation period)

The MPR was converted to a categorical variable. Patients with an MPR of ≥80% were labeled adherent. While the use of 80% is arbitrary, it is a frequently reported threshold in published literatureCitation11,Citation15.

Any patients who were not labeled as adherent were further classified into one of the following three types of non-adherence: intermittently adherent, drop-offs or switchers. Intermittently adherent was defined as having evidence of continued availability of infliximab, but not receiving infusions according to recommended dosing intervals. For patients who were less than 80% adherent, the first and last date of infliximab therapy was identified. Patients who had a time between infusions that spanned more than 90% of the 360-day observation period, regardless of how the medication was used between these dates, were placed in this group. The 90% criterion was based on the following formula:

This approach assumes that patients who had prescriptions that spanned 90% or more of the observation period (i.e., a minimum of 324 days out of 360 days of observation) did not have issues with lack of efficacy or tolerability. We considered this population to be the most robust group for evaluating adherence effects with the potential effects of lack of efficacy or tolerability removed.

The remaining patients were classified as drop-offs or switchers. Drop-offs had less than 80% coverage of days in the post-index year, less than 90% of days between the first and last infliximab infusion, and had no evidence of any other inflammatory bowel disease treatment (6-mercaptopurine, aminosalicylates, azathioprine, corticosteroid, cyclosporine, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, or tacrolimus) after their last infliximab infusion. Switchers met these same criteria, except they had a non-infliximab inflammatory bowel disease medication claim after the last infliximab infusion.

The primary analysis compared adherent and intermittently adherent groups. For the primary analysis, the pattern of non-adherence was considered important because some patterns such as dropping off therapy or switching therapies might be more likely to reflect tolerability issues or lack of efficacy rather than behavior that would lead to a lack of compliance. A secondary analysis compared adherent vs non-adherent patients for any reason. The secondary independent variable was a categorical variable indicating either being adherent or non-adherent with infliximab for any reason (i.e., combining intermittent use, drop-offs or switchers). The cohort consisted of patients who met either the adherent or ‘non-adherent for any reason’ definition. The relationship between the primary and secondary analysis and the adherence definitions is shown in .

Outcomes

The primary outcome measure was total cost per patient calculated from the US payer perspective. Total cost included the following: total non-infliximab costs, inpatient costs, outpatient costs (with and without infliximab), emergency room costs, and pharmacy costs. CD-related costs were also evaluated as a sub-set of the all-cause costs. Because study data extended beyond 1 year, all costs were discounted to December 2010 using the medical services component of the Consumer Price IndexCitation16. Healthcare resource utilization was also evaluated for the presence of a fistula repair or colectomy (total or partial) and the number of hospitalized days.

Statistical analysis

Given the observational nature of the analysis, differences in patient characteristics prior to using infliximab for the adherent and non-adherent groups could lead to biased conclusions. Several methods for addressing imbalances between groups were considered (e.g., direct adjustment, propensity matching, propensity weighting). Propensity weighting was selected due to the relatively small and similar sample sizes between the groupsCitation17. Propensity scores were developed using a non-parsimonious logistic regression model. The propensity score was the conditional probability of being adherent, based on each subject’s pre-treatment variables. Graphs of propensity score logits by adherence group were used to check for overlap (i.e., identify the region of common support) of the propensity score distributions. Tails of the propensity score distributions and sensitivity analysis by removal of outliers (so that they do not exert undue influence) was evaluated.

The outcomes assessment model used a propensity weighting approach to estimate the average treatment effect in the treated (ATT). The ATT weighting scheme creates a sample of non-adherent patients that have the same distribution of propensity for being adherent as the adherent group. A wide range of variables from the pre-index period were used to construct the propensity model. Because of the relatively large number of variables they are not listed here, but are presented in the Results section.

The dependent measures were evaluated using a generalized linear model with robust variance estimation (implemented with PROC GENMOD using SAS 9.2 for Windows). The generalized linear model allows the mean to depend on a linear predictor through a non-linear link function and allows the response probability distribution to be any member of the exponential family of distributions. Cost models were evaluated using a log link with a gamma distribution. For component costs where zero values were possible, a nominal amount was added. Presence of a procedure to repair a fistula and presence of a colectomy were evaluated with a log link and a binomial distribution. Number of hospital days was evaluated with a log link and a Poisson distribution. All statistical tests were two-sided and conducted at the 5% significance level. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS, version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

shows the sample attrition results. There were 5259 patients who had two CD diagnoses with at least one infliximab prescription during the time periods of interest. After application of the remainder of the inclusion and exclusion criteria there were 945 CD patients available for analysis.

Table 1. Sample attrition for Crohn’s patients.

presents the results of the adherence assignments. A total of 38.1% of patients were labeled as adherent and 25.3% were labeled as intermittently adherent. These 599 patients were used for the primary analysis. The secondary analysis used the 585 subjects who were non-adherent for any reason (intermittent plus switched or dropped-off).

Table 2. Compliance group assignments for patients with Crohn’s disease.

The adherent group was 48.6% female and had an average of 42.6 (SD = 15.3) years of age. This compared to 54.4% female and an average age of 43.4 (SD = 15.8) in the intermittently adherent group (). The regional distribution between groups was similar.

Table 3. Crohn’s disease patient characteristics.

The non-parsimonious logistic regression model used to develop the propensity scores used the following pre-index variables: age; an indicator for whether infliximab was initiated during 2009 (index year); gender; insurance type; Medicare status; smoking status; comorbidity measures; markers for presence of a diagnosis based on the major chapter heading of the ICD-9-CM coding manual for infectious and parasitic diseases (001.XX–139.XX), neoplasms (140.XX–239.XX), endocrine (240.XX–279.XX), blood disease (280.XX–289.XX), nervous system (320.XX–389.XX), respiratory system (460.XX–519.XX), genitourinary (580.XX–629.XX), skin disease (680.XX–709.XX), musculoskeletal (710.XX–739.XX), ill-defined conditions (780.XX–799.XX), injury and poisoning (800.XX–999.XX), or supplementary classification diagnoses (includes items such as annual indicators for long-term use of high risk medications and special laboratory examinations; V01.XX–V82.XX); specific comorbidities included depression (296.2X, 296.3X, 300.4X, 311.XX), hypertension (401.XX), diabetes (250.XX), COPD (490.XX, 491.XX, 492.XX, 494.XX, 496.XX), irritable bowel syndrome (564.1X), and GERD (530.81); office for first infliximab infusion; outpatient hospital for first infliximab infusion; presence of a bowel procedure; percentage of days on ciprofloxacin, metronidazole, aminosalicylates, corticosteroids, or 6-mercaptopurine; pre-period emergency room, inpatient, outpatient and pharmacy costs, number of pre-period hospital and ER visits; number of pre-period gastroenterologist visits; number of pre-period outpatient visits; and number of pre-period colonoscopies.

The model provides insights about variables that were imbalanced at initiation of infliximab between the adherent and intermittently adherent groups. highlights those that were significant predictors of adherence at probabilities of less than 0.10. Patients who had their first infliximab infusion in an office ‘place of service’ had the highest odds of being adherent at 3.6-times that of patients who did not have their first infusion administered in an office setting. Patients with a previous bowel procedure had odds that were 2.7 greater than patients without a bowel procedure. Each colonoscopy increased the odds of being adherent by 2.6-times. Males were twice as likely to be identified as adherent as females. The propensity weighting was used to develop weights that adjusted for imbalances between the adherent and intermittently adherent groups.

Table 4. Variables in the logistic regression model used to develop propensity weights whose p-values were ≤0.1.

In addition, graphs of propensity score logits by adherence groups indicated significant overlap in the propensity scores. Overlap of propensity scores for both the adherent and non-adherent patients provided evidence that both groups had representation across the range of propensity scores. Sensitivity analyses for the results were conducted by removal of outliers. No conclusions of the analysis changed.

Outcomes

The propensity weighted cost model for the CD cohort revealed similar total costs for the adherent ($40,425, 95% CI = [$38,686, $42,242]) vs the intermittent groups ($41,082, 95% CI = [$38,163, $44,223]; p = 0.7125, ). Thus, the conservative nature of this evaluation was supported by the cost of exposure to infliximab in the intermittently adherent group. Among intermittently adherent patients, infliximab costs (i.e., a proxy for exposure) were $21,014 (95% CI = [$18,798, $23,490]) compared to $27,328 (95% CI = [$25,570, $29,207]; p ≤ 0.0001) in the adherent group. Since the adherent group had ∼25% higher infliximab costs (i.e., more exposure), the non-infliximab cost comparison results were of strong interest. For the total costs with infliximab removed, the difference between adherent and intermittent groups was substantial and greater for the intermittent group: $13,097 (95% CI = [$12,141, $14,127]) vs $20,068 (95% CI = [$17,676, $22,784]; p = 0.0001). Non-infliximab outpatient costs were also greater for the intermittent group ($10,196; 95% CI = [$9103, $11,421]) vs adherent ($7074; 95% CI = [$6611, $7569]; p < 0.0001). The largest difference in the component costs, however, were for inpatient hospitalizations where the costs were $2764 (95% CI = [$2149, $3556]) in the adherent vs $6665 (95% CI = [$4369, $10,165]) in the intermittently adherent group (p = 0.0002). Emergency room and other pharmaceutical costs were not statistically different. CD-related costs showed similar trends.

Table 5. Crohn’s outcomes models using average treatment effect in the treated (ATT) weights derived from propensity scores.

Fistula repairs and colectomies occurred in a small portion of the sample (<5%) and the propensity weighted estimates were not statistically different between adherent and intermittent groups. As expected, the weighted average number of hospital days was significantly different 1.0 (SD = 1.9) vs 2.7 (SD = 3.8, p < 0.0001) for all cause and 0.6 (SD = 1.4) vs 1.6 (SD = 2.2, p < 0.0001) for hospitalization labeled as CD-related for adherent and intermittently adherent patients, respectively.

The secondary analysis evaluated the adherent vs non-adherent (includes intermittently adherent, drop-offs, and switchers; n = 585). This comparison provided a less restrictive measure of the effect of adherence, since it included drop-offs and switchers. The overall costs were not significantly different (p = 0.1714). Costs with infliximab removed were $12,624 (95% CI = [$11,631, $13,701]) in the adherent group and $27,286 (95% CI = [$25,158, $29,594]) in the non-adherent group (p < 0.0001). Again, the dominant cost driver was inpatient hospitalization, which was $2628 (95% CI = [$2059, $3355]) in the adherent group and $12,423 (95% CI = [$9751, $15,826]) in the non-adherent group (p < 0.0001). Non-infliximab outpatient costs in the adherent group were $6825 (95% CI = [$6342, $7344]) vs $11,109 (95% CI = [$10,330, $11,948]) in the non-adherent group (p < 0.0001). Emergency room costs were lower in the adherent group, $295; 95% CI = [$243, $358] vs $512; 95% CI = [$423, $621] in the non-adherent group (p < 0.0001). Other pharmaceutical costs did not differ statistically.

Discussion

This study presents a novel approach for analyzing adherence effects in that it attempts to remove the variances in cost estimates that are due to lack of tolerability and or efficacy. This strategy provides a conservative estimate of the economic and clinical consequences of adherence since, although the non-adherent group has persistent exposure to infliximab therapy, these patients appear to be missing doses. Our primary finding was that, although total costs were similar between the two groups, Crohn’s disease patients who were adherent to infliximab have lower direct medical costs, exclusive of the cost of infliximab, than patients who are non-adherent. This difference was driven by both lower inpatient and outpatient costs. When examining adherent vs non-adherent differences, which is more consistent with data that has been presented in the literatureCitation18, the statistical findings were similar; however, the magnitude of the differences was greater than for the adherent vs intermittently adherent comparison. This methodology-related difference in estimates suggests that the economic effects of adherence may be over-stated when only adherent vs non-adherent comparisons are used for these comparisons. Again, the concept that some of the non-adherent patients are not truly non-adherent is contestable in the sense that adherence is a volitional act; these individuals may have issues with tolerability or efficacy. Significant findings were not observed for the number of colectomies or fistula repairs, although this finding was not entirely unexpected given the relatively small sample and the short time period (360 days) of observation.

One of the most interesting findings from the propensity analysis suggested that site of the first infusion might be related to adherence status. Patients who had their first infliximab infusion in an office ‘place of service’ had an odds of being adherent that were more than 3-times greater than patients who did not have their first infusion administered in an office setting. This result raises questions as to whether the observed non-compliance is patient-related or related to the system of physician follow-up. This finding suggests that additional analysis regarding the value of physician services in maintaining compliance on biologics is warranted.

The propensity analysis also indicated that males were twice as likely to be adherent as females. While this finding was not expected, it is important to note that the data are among those that are adherent and intermittently adherent to infliximab therapy. As such, there is limited published data available to confirm this observation among ‘adherent’ patients. One study identified in the literature suggested that female gender is a risk factor for non-adherence to infliximab therapy in CD patientsCitation6. Additionally, use of a non-parsimonious logistic regression model may have introduced correlations that reduce the interpretability of the parameter estimates.

This study was based on a retrospective analysis of outpatient and hospital administrative claims data. As such, the analysis uses medical coding for assignment of patients to groups. There is no way to clinically verify patient status. Results are only comparable to the extent that the propensity weighting is capable of adjusting for group differences based on observed variables or unobserved variables that are correlated with the observed variables. While indirect costs are expected to be a significant component of the total burden of illness for inflammatory bowel disease patients, these costs are not available in the administrative database. No evaluation of indirect costs was conducted; however, this is noted as a limitation since it could have a significant impact on the overall burden of illness. Alternative definitions of adherence and non-adherence could lead to different results. There is little standardization in the literature with regard to calculation of adherence. The direction of the causal relationship between hospitalizations and adherence has not been confirmed and may be a topic for future research. The goal of the methodology was to obtain an adherence measure that more nearly reflected patient behavior by removing patients who might be experiencing tolerability or lack of efficacy issues. It remains possible that physicians were prescribing intermittent therapy and lack of adherence may not be due to patient-centric reasons. It is not possible to assess the likelihood of intermittent prescribing in this administrative database. It is noted that other systematic reasons may exist for people not consistently using infliximab that are not directly related to patient choices on utilization. The methodology proposed in this analysis has not been validated. Results are dependent on the accuracy of the paid claims data and the assumptions made about duration of action of the therapy.

Conclusions

This analysis developed a novel approach for investigating gradations within the group that has traditionally been labeled as non-adherent. Future steps in the validation of this measure include developing rigorous studies to establish appropriate cut-points for categorizing a patient as intermittently adherent. For this analysis, the cut-points were established a priori by the researchers based on clinical judgment. Future research should also look at stratifying the intermittent users to evaluate the different levels of intermittent use. Finally, one of the most interesting findings was the suggestion that place of service may have an impact on the likelihood of being adherent. A plausible explanation for this observation is that better follow-up occurs when the initial dose of infliximab is administered in an office as opposed to another location (e.g., outpatient hospital or alternative site of care). Investigation of the associations between site of administration and adherence are warranted.

The concept of intermittent adherence is a novel approach that potentially removes patients who discontinue because of lack of tolerability or efficacy. We found that non-infliximab-related costs were lower in adherent than in intermittently adherent or non-adherent patients due to considerably lower costs of hospitalization and outpatient care. These results demonstrate that the higher drug acquisition costs related to biological therapy are offset by important cost reductions and improved clinical outcomes. Further research regarding the value of physician services in maintaining compliance on biologics is warranted.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

Research funding was provided by Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

Employees of Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC (JSA) participated in the design of the study, the analysis of the data, and the preparation of the paper. CK and TS received research funding from JSA. BF was a paid study consultant who has received research funding from JSA and GW and WO are employees of Janssen a member of Johnson & Johnson family of companies. JME peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Tecca Wright for assistance in the preparation of the manuscript. This manuscript was presented in part as an oral presentation at the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research Annual Meeting, June 2–6, 2012, Washington, DC.

References

- Hanauer SB. Inflammatory bowel disease: epidemiology, pathogenesis, and therapeutic opportunities. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2006;12:s3-9

- Cosnes J, Cattan S, Blain A, et al. Long-term evolution of disease behavior of Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2002;8:244-50

- Feagan BG, Lémann M, Befrits R, et al. Recommendations for the treatment of Crohn’s disease with tumor necrosis factor antagonists: an expert consensus report. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2012;18:152-60

- Lichtenstein GR, Yan S, Bala M, et al. Remission in patients with Crohn’s disease is associated with improvement in employment and quality of life and a decrease in hospitalizations and surgeries. Am J Gastroenterol 2004;99:91-6

- Burger D, Travis S. Conventional medical management of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 2011;140:1827-37.e2

- Kane S, Dixon L. Adherence rates with infliximab therapy in Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2006;24:1099-103

- Carter CT, Waters HC, Smith DB. Effect of a continuous measure of adherence with infliximab maintenance treatment on inpatient outcomes in Crohn’s disease. Patient Prefer Adherence 2012;6:417-26

- Kane SV, Chao J, Mulani PM. Adherence to Infliximab Maintenance Therapy and Health Care Utilization and costs by Crohn’s Disease Patients. Adv Ther 2009;26:936-46

- Carter CT, Waters HC, Smith DB. Impact of infliximab adherence on Crohn’s disease-related healthcare utilization and inpatient costs. Adv Ther 2011;28:671-83

- Selinger CP, Robinson A, Leong RW. Clinical impact and drivers of non-adherence to maintenance medication for inflammatory bowel disease. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2011;10:863-70

- Cramer JA, Roy A, Burrell A, et al. Medication compliance and persistence: terminology and definitions. Value Health 2008;11:44-7

- Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Reinisch W, et al. Infliximab, azathioprine, or combination therapy for Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med 2010;362:1383-95

- Baert F, Noman M, Vermeire S, et al. Influence of immunogenicity on the long-term efficacy of infliximab in Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med 2003;348:601-8

- Fefferman DS, Farrell RJ. Immunogenicity of biological agents in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2005;11:497-503

- Trindale AJ, Ehrlich A, Kornbluth A, et al. Are your patients taking their medicine? Validation of a new adherence scale in patients with inflammatory bowel disease and comparison with physician perception of adherence. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2011;17:599-604

- US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. All Urban Consumers, medical services component, Consumer Price Index. Washington D.C., USA http://www.bls.gov. Accessed May 20, 2014

- Lunceford JK, Davidian M. Stratification and weighting via the propensity score in estimation of causal treatment effects: a comparative study. Stat Med 2004;23:2937-60

- Wan GJ, Kozma CM, Slaton TL, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease: Healthcare costs for patients who are adherent or non-adherent with infliximab therapy. J Med Economics 2014;17:384-93