Abstract

Objective:

Across Italy up to 7.3% of the population is infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV), with long-term complications resulting in high medical costs and significant morbidity and mortality. Current treatment options have limitations due to side effects, interferon intolerability and ineligibility, long treatment durations and low sustained virological response (SVR) rates, especially for the most severe patients). Sofosbuvir is the first nucleotide polymerase inhibitor with pan-genotypic activity. Sofosbuvir, administered with ribavirin (RBV) and with or without pegylated interferon (PEG-INF), resulted in >90% SVR across treatment-naïve (TN) genotype (GT) 1–6 patients. It is also the first treatment option for patients that are unsuitable for interferon (UI). This analysis evaluates the cost – effectiveness of sofosbuvir for GTs 1–6 in Italy.

Research design and methods:

A Markov model followed a cohort of 10,000 patients until they reached 80 years old. Approximately 20% of naïve and 30% of experienced patients initiated treatment at the cirrhosis stage. Comparators included PEG-INF + RBV for all GTs and plus telaprevir or boceprevir for GT1, or no treatment. Costs and outcomes were discounted at 3% and the cost perspective was that of the National Health Service in Italy.

Results:

Sofosbuvir was cost-effective with incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) below €40,000/QALY in all patient populations, particularly in cirrhotic patients. The exception was for a mixed cohort of GT2 TN patients where the ICER was €68,500/QALY and for a cirrhotic cohort of GT4/5/6 where the ICER was €68,434/QALY. Nevertheless, the prevalence of HCV in this patient population is expected to be low. Results were robust to sensitivity analysis.

Conclusions:

Sofosbuvir-based regimens are cost-effective in Italy, particular for the most severe patients. The interferon-free regimens are a real treatment option for UI patients. The high cure rates of this breakthrough treatment are expected to substantially reduce the burden of HCV in Italy.

Introduction

Hepatitis C is an infectious liver disease that is caused by the hepatitis C virus (HCV). In most infected individuals, the disease is asymptomatic in the early stages and in an estimated 15%–25% of the patients it resolves itself causing no long-term damage to the liver. However, the majority of patients, approximately 75%–85%, progress to develop chronic hepatitis C infection (CHC). The risk of developing liver cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is significantly higher among CHC patients. It is estimated that, over a period of 20 years, 10%–15% of patients with CHC eventually develop liver cirrhosis. Of these, an estimated 1%–4% of patients develop HCCCitation1.

The disease is associated with significant morbidity, mortality and economic burden. Worldwide, it is estimated that approximately 180 million people are infected by the virus, accounting for nearly 3% of the world populationCitation2. In Italy, the prevalence of the infection varies considerably according to the geographical region. In northern Italy, the overall prevalence of HCV infection was estimated to be 1.6%, while in central and southern Italy the prevalence was estimated to be considerably higher, approximately 6.1% and 7.3%, respectivelyCitation3. According to a recent cost-of-illness study, the health care costs of HCV infection increased with the severity of the liver disease. While monthly costs associated with the treatment of CHC patients in Italy were estimated to be €240 per patient, the per patient monthly treatment costs associated with more severe conditions such as cirrhosis, HCC and liver transplantation (LT) were estimated to be €500, €1230 and €2680, respectivelyCitation4.

Overall, the total direct and indirect cost of treating diseases related to HCV in Italy is estimated to be approximately 800 million Euros annuallyCitation5.

HCV is a genetically heterogeneous virus and several genotypes and subtypes of the virus have been identified. Of these, GT1 is the most prevalent form of the virus worldwideCitation6. In Italy, the most common genotypes of HCV are GT1, GT2 and GT3, accounting for 58%, 17% and 17% of all HCV infections, respectivelyCitation7. Treatments for HCV vary according to the viral genotype. In Italy, current treatment options for patients with GT1 virus include dual therapy with PEG-INF + RBV, which accounts for 45% of all treatments in GT1Citation7, and triple therapy with a protease inhibitor (PI) (telaprevir or boceprevir) in combination with PEG-INF + RBV. Dual therapy is the only available treatment for patients with GT2 and GT3.

PI-based regimens that offer higher SVR rates compared to the conventional dual therapy with PEG-INF + RBV are an alternative for GT1 patients. However, the probability of reaching SVR is low in treatment-experienced (TE) patients, especially among null responders. Of all patients diagnosed with HCV infection, only approximately 20% initiate treatment and as a low as 3% to 4% of the total diagnosed population achieves a SVRCitation8. Furthermore, triple therapy regimens are not an option for patients intolerant, unwilling or contraindicated for interferon therapyCitation9. The current therapies are also less attractive due to long and complicated treatment regimens, frequent intolerable side-effects that have led to treatment discontinuations in real world settings in excess of 30% and the development of treatment-resistant and cross-resistant viral mutations which can lead to treatment failureCitation10,Citation11.

Thus there is an evident unmet medical need for new treatments options in HCV-related diseases, which provide shorter, simpler, better tolerated and more effective pan-genotypic regimens. In particular, there is a need for regimens with a high barrier to resistance and no drug-to-drug interactions, those that can reduce or eliminate the limitations associated with long-term or side effects and contraindications to current available therapies including interferon use.

Sofosbuvir (SOF) is the first nucleotide polymerase inhibitor with pan-genotypic activity and a high barrier to resistance. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) has approved SOF in combination with RBV with or without PEG-INF, for 12 or 24 weeks according to GT and interferon status, for the treatment of adult CHC patients with one of the six major HCV GTs: GT1/2/3/4/5/6Citation12. It is the first all-oral treatment option to be approved for patients unsuitable for interferon (UI) and is also available for patients co-infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). In treatment-naïve (TN) patients, with the exception of GT3 UI patients, SOF in combination with RBV with or without PEG-INF was associated with 12 week SVR rates of more than 90% across all genotypes. The safety profile of SOF has meant that even the most severe patients now have the opportunity of a cure, including those waiting for transplant. In view of the superior efficacy and safety profile, SOF has been recommended by the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) as the preferred backbone treatment for all major genotypes of HCVCitation13. The recently published EASL recommendations on treatments for HCV also highlight:

Indications for HCV treatment in HCV/HIV co-infected persons are identical to those in patients with HCV mono-infection (Recommendation A1)

The same treatment regimens can be used in HIV co-infected patients as in patients without HIV infection, as the virological results of therapy are identical (Recommendation A1)

No drug–drug interaction has been reported between SOF and antiretroviral drugs (Recommendation A2).

Methods

Model structure

The Markov state-transition model developed for this analysis represents the natural history of CHC and is based on the economic models published by the Southampton Health Technology Assessment Centre (SHTAC) in the UK for the National Institute for Health and Clinical excellence (NICE)Citation14,Citation15.

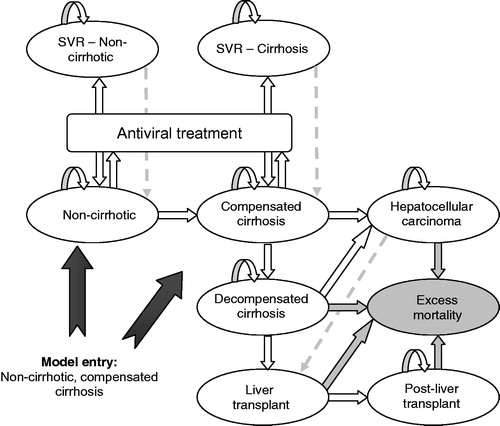

illustrates the disease pathway model. Patients enter the model in the non-cirrhotic (METAVIR scores F0–F3) or cirrhotic (METAVIR score F4) health states and are treated with anti-viral therapy. On completion of treatment (at 12 or 24 weeks for SOF and up to 48 weeks for the comparator treatments), patients who achieve SVR are considered to be permanently cured of the infection (SVR at 12 weeks has been established as an appropriate endpoint for regulatory approval and is accepted by most clinical and regulatory authoritiesCitation16) and these patients are assumed to remain in the ‘SVR’ health state for their remaining lifetime. We test this assumption in the sensitivity analysis by considering recurrence and re-infection of HCV for both non-cirrhotic and cirrhotic patients (depicted by the grey dashed arrows). Patients who do not achieve SVR progress to more advanced stages of the disease such as decompensated cirrhosis (DCC), HCC or LT. The probability of requiring a LT on developing HCC is also explored in the sensitivity analysis.

Figure 1. Markov model schematic for chronic hepatitis C. Patients can die in each health state. The grey health state ‘excess mortality’ represents the disease-specific mortality associated with having DCC, LT or HCC. Dashed arrows represent health state transitions only investigated in sensitivity analysis. DCC, Decompensated cirrhosis; HCC, Hepatocellular carcinoma; LT, Liver transplant; SVR, Sustained virological response.

Age-specific all-cause mortality rates were applied to all health states in the model. In addition, disease-specific mortality was also assumed for patients in advanced stages of the disease. The excess mortality associated with these health states is depicted by the grey arrows.

The model splits patients between non-cirrhotic (F0–F3) and cirrhotic (F4) in line with the design of the SOF clinical trials. No liver biopsy was made at study entry and cirrhosis was assessed using Fibroscan and/or Fibrotest, which do not perform as well as liver biopsy when evaluating moderate disease. Therefore separate health states for F0 to F3 METAVIR score could not be modeled.

The analysis considered a lifetime horizon (until patients reached 80 years of age). The cycle length was 3 months for the first 2 years, to account for the 12 week treatment duration for some SOF regimens, and yearly thereafter. A half-cycle correction was implemented to account for the longer cycle length following the first 2 years. The model was based on the Italian National Health Service (NHS) perspective and thus included only direct healthcare costsCitation17. The proportion of patients initiating treatment at the cirrhotic stage for each genotype, mean age at treatment and mean patient weight were based on data from the PROBE study, a large prospective multicentre cohort study, and clinical opinionCitation18. Approximately 20% of TN and 30% of TE patients initiated treatment at the cirrhosis stageCitation19. Costs and outcomes were discounted at 3% as recommended by the Italian Association of Health Economics (AIES)Citation20.

Model population

The analysis was representative of the patient populations assessed in five phase III randomized trials for SOF – NEUTRINO, FISSION, POSITRON, FUSION, and VALENCE – and five phase II randomized trials – QUANTUM, SPARE, ELECTRON, PROTON and LONESTAR-2Citation12. The analysis also included GT1 TE patients according to the observational study TRIOCitation21.

The cost-effectiveness analysis assessed the SOF regimen for the following HCV patient groups:

Genotype 1: TN or TE who are IE or TN UI patients

Genotype 2: TN or TE patients who are IE or UI

Genotype 3: TN or TE patients who are IE or UI

Genotype 4/5/6: TN IE patients.

Model inputs

Treatment strategies

The intervention and the comparator treatment strategies were defined based on the marketing authorizations and licensed doses for the respective patient populationCitation12,Citation22,Citation23.

Efficacy: SVR rates

The SVR rate of SOF for each patient group was taken from the studies presented above. The SVR rate of each comparator was also derived from SOF trials where possible; otherwise, we obtained these from the literature (). The SVRs included in the GT1 and GT2/GT3 TE IE analyses were likely to favor the comparator rather than SOF. For example, for GT1 TN patients SVRs for telaprevir were taken from a phase III trial (ADVANCE) that included healthier patients. For GT2/GT3 TE IE SVR rates for PEG-INF were assumed to be the same regardless of whether the patients were non-cirrhotic or cirrhotic.

Table 1. SVR by indication.

Transition probabilities

Transition probabilities (TPs) for the analyses were taken from the literatureCitation14,Citation15 (). TPs from the non-cirrhotic to compensated cirrhosis (CC) health state were based on estimates used by Grishchenko et al.Citation24. Since this study reported separate age-specific TPs for mild to moderate and moderate to CC, TPs were estimated by using a two-state Markov model (non-cirrhotic to CC) (see supplementary materials for further details).

Table 2. Transition probabilities.

Annual mortality rates, by age group, were obtained from the National Institute for Statistics (ISTAT)Citation25. These estimates were converted to annual and 3 month probabilities for the analysis.

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL)

Utilities for health states considered in the analyses were taken from the UK trial on mild HCV by Wright et al. (see supplementary materials for further details)Citation26. The treatment-related utility decrements for SOF were obtained from the respective phase III clinical trialsCitation27. Utility decrements for the comparators i.e., PEG-INF + RBV and PIs (telaprevir and boceprevir) were taken from Wright et al. and the NICE technology appraisals, respectivelyCitation26,Citation28,Citation29.

Quality of life (QoL) data in the Gilead clinical trials were collected at the following time points: baseline, 12 weeks/early termination, 4 weeks post-treatment, 12 weeks post-treatment and 24 weeks post-treatment. As the SF-36 was used to measure QoL in the clinical trials, these estimates were mapped to SF-6D and EQ-5D using the algorithms published by Brazier et al. 2002Citation30 and Gray et al. 2004Citation31, respectively.

The SF-6D values were used in the base case analysis as these utilities were obtained from a well validated conversion method. In the deterministic sensitivity analysis (DSA), the ranges for the utility decrements for SOF were adjusted to include the EQ-5D values.

Resource use and costs

For SOF, we used the ex-factory price, which is equal to €45,000 for 12 weeks of treatment. In addition, as part of the reimbursement agreement with the Italian reimbursement agency, we assumed that 24 weeks of treatment with SOF had the same price as 12 weeks of treatment. Drug costs for all the comparators included in the analysis are those applied to the Italian NHS hospitals (see supplementary materials for further details).

Resource use associated with treatment-related adverse events and routine patient monitoring were based on clinical opinion. Costs included outpatient care, general practitioner (GP), specialist visits and drug costs. Drugs selected to treat each adverse event were valued at consumer prices, whereas laboratory tests, instrumental exams, specialist visits and hospitalizations were valued with national tariffsCitation32.

The costs of monitoring patients being treated with either SOF or the comparator strategy were also included in the analysis. Resource use estimates were based on clinical opinion, and tariffs were used for valuing resource consumption.

Costs associated with each health state were obtained from the White Paper by the Italian Association of the Study of the Liver (AISF)Citation19. These health state costs are independent from the monitoring costs and represent the cost associated with each health state post-treatment (see supplementary materials for further details).

Model outcomes

Clinical outcomes included the number of cases of CC, DCC, HCC, LT and lives saved, the number of life years (LYs) and the quality adjusted life years (QALYs) gained. Economic outcomes included treatment and other health care costs, costs saved per CC/DCC/HCC/LT avoided and the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER). ICERs were calculated as the ratio of the difference in costs and outcomes (QALYs or LYs gained) between the SOF regimen and the comparator. According to the AIES an ICER between €25,000/QALY and €40,000/QALY is generally considered cost-effective in ItalyCitation17.

Sensitivity analyses

To assess the uncertainty in the results, deterministic and probabilistic sensitivity analyses were conducted. The following inputs were varied in the DSA: costs associated with treatment (including drug, AEs and monitoring costs), SOF drug cost (varied by less 20%), health state costs, utility weights, TPs (including recurrence and re-infection rates of 1%), discount rates, the probability of death for the general population, percentage of patients who are cirrhotic, SVR rates, health state costs, health state utilities, treatment-related utility decrements, the utility increment after reaching SVR and incidence of adverse events. These parameters were varied based on the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) reported in Shepherd et al.Citation13, the SOF clinical trials or by varying the base case by 20 or 25% more or less.

In the probabilistic sensitivity analysis (PSA), health state utilities, treatment-related utility decrements and the increment after reaching SVR, treatment and health state costs, TPs and SVR rates were varied. Utility decrements/increments and health state costs were assumed to follow a gamma distribution. Health state utilities associated with the different Markov states and SVR rates were assumed to follow a beta distribution.

Results

Base case analysis

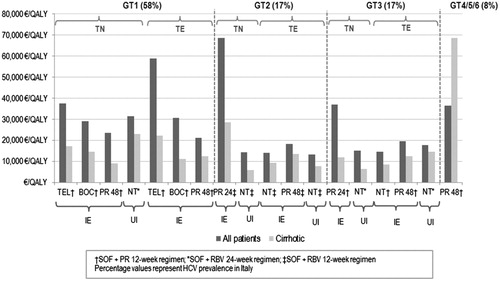

Overall, the SOF-based regimens offer a favorable cost-effectiveness profile compared with current standard of care for the six major HCV genotypes (GT1-6) (). This was based on the €40,000/QALY threshold that is generally considered in ItalyCitation17. The SOF-based regimens also induced significant improvements in health outcomes and long-term complications across all genotypes and patient populations considered in this analysis ( and ).

Table 3. Summary of results per indication for a mixed cohort.

Table 4. Summary of results per indication for a cirrhotic cohort.

In TN IE GT1 patients, the results of 12 week SOF + PEG-INF + RBV were considered to be cost-effective ranging from €23,392/QALY versus 48 week PEG-INF + RBV to €37,334/QALY versus telaprevir. The ICER for the 24 week SOF + RBV regimen versus no treatment was also considered to be cost-effective among the TN UI GT1 patients (€31,393/QALY). This provides a therapeutic option for UI patients who previously had no effective treatment alternatives. In terms of the TN IE GT1 cirrhotic patients treated with 12 week SOF + PEG-INF + RBV, the ICERs/QALY obtained were even more cost-effective (€9087, €14,499 and €17,220 versus 48 week PEG-INF + RBV, boceprevir and telaprevir, respectively) in this population. The ICER/QALY was also considered cost-effective in TN UI GT1 cirrhotic patients (€22,839 versus no treatment). In terms of cost per life years (LY) gained, SOF was associated with ICERs from €35,105 versus PEG-INF + RBV to €45,394 versus telaprevir for TN IE GT1 patients and €51,282 for TN UI GT1. An investigation of the mortality, LT and HCC events demonstrated that SOF was associated with fewer cases in all instances.

In TE IE GT1 patients, SOF produced ICERs that ranged from €21,087 versus 48 week PEG-INF + RBV to €58,700 versus telaprevir. For cirrhotic patients, ICERs/QALY ranged from €11,158 versus boceprevir regimen to €22,078 versus telaprevir therapy. The ICERs/LY obtained were equal to €27,997 versus PEG-INF + RBV, €41,418 versus boceprevir and €112,742 versus telaprevir. All SOF regimens resulted in improved clinical outcomes compared to PEG-INF + RBV, BOC + PEG-INF + RBV and TPV + PEG-INF + RBV.

The 12 week SOF + RBV regimen was considered cost-effective in TN/TE UI and TE IE GT2 patients when compared to 48 week PEG-INF + RBV and no treatment with all ICERs/QALY below €18,325 (mixed cohort) and €13,465 (cirrhotic cohort). However, in TN IE GT2 patients when the regimen was compared to 24 week PEG-INF + RBV, the ICER/QALY increased to €68,500 and €28,490 in the mixed and cirrhotic cohorts, respectively. In terms of cost per LY, SOF regimens produced ICERs that ranged from €16,708 for GT2 TE UI versus no treatment to €95,544 for GT2 TN IE versus PEG-INF + RBV.

Based on a threshold of €40,000/QALY, 12 week SOF + PEG-INF + RBV was also cost-effective in both the GT3 IE and UI population when all comparators were considered. The ICER/QALY was its highest when compared to 24 weeks of PEG-INF + RBV in TN IE GT3 patients (€36,924). The investigation of only cirrhotic patients demonstrated cost-effectiveness in all instances. All SOF regimens were associated with significant improvements in mortality, LT and HCC. The ICERs/LY obtained ranged from €18,235 for GT3 TE IE versus no treatment to €44,767 for GT3 TN IE versus PEG-INF + RBV.

In GT 4/5/6 TN IE patients, 12 week SOF + PEG-INF + RBV was within the range considered to be cost-effective (€36,444) when compared to 48 week PEG-INF + RBV. In terms of cost per LY gained, SOF + PEG-INF + RBV was associated with an ICER equal to €102,419. These results are promising given that the SVRs for cirrhotic patients (50%) and non-cirrhotic patients (100%) treated with SOF were based on a small number of patients. In addition, the SOF-based regimen was associated with a more favorable clinical profile compared to the 48 week PEG-INF + RBV regimen in terms of mortality, LT and HCC avoided.

Sensitivity analysis

The DSA demonstrated that the base case ICERs were sensitive to the discount rates applied to both costs and outcomes and the utility increments following SVR. In all patient populations UI, the results were also sensitive to changes to the transition probability from non-cirrhotic to compensated cirrhosis. The decrease by 20% of the cost per pack for SOF did not substantially change the results originating ICERs below €24,682 in GT1 (for patients TN UI). In GT2 ICERs ranged from €9893 in GT2 TE UI to €52,206 in GT2 TN IE. For GT3 patients, they ranged from €11,069 in GT3 TE IE (versus no treatment) to €28,285 in GT3 TN IE. Finally, in GT4/5/6, this lower price generated an ICER of €26,769.

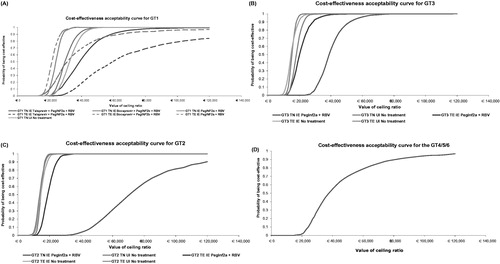

The probability of SOF being cost-effective at a willingness to pay threshold of €40,000/QALY is illustrated in .

In GT1 TN IE patients it ranged from 54% versus telaprevir to 100% versus 48 week PEG-INF + RBV. For patients UI the probability was 88%. In GT1 TE IE, it ranged from 19% versus telaprevir to 100% versus 48 week PEG-INF + RBV.

In GT2 patients there was 100% probability of cost-effectiveness across all indications and comparators except for TN INF eligible patients where the probability fell to 4%.

In GT3 TE patients both IE and UI, there was a high probability of being cost-effective (approximately 100%) across all indications. The TN UI also had 100% probability of being cost-effective. This decreased to 56% in the TN IE population.

In GT4/5/6 patients the probability was approximately 55% versus 48 week PEG-INF + RBV.

Discussion

The treatment regimens for HCV that are centered on PIs and PEG-INF + RBV have generated significant improvements in SVR rates for GT1 patients. Although PIs have really improved the treatment of HCV patients compared to PEG-INF + RBV, the latter is still widely used across Italy. However, besides their poor tolerability profile, these treatment options are not suitable for UI patients and other genotypes. Therefore, there is a need for new better tolerated and more effective pan-genotypic regimens in these populations. The current trend in the treatment of HCV has been the development of regimens suitable for hard-to-treat populations and SOF is the first all-oral treatment with pan-genotypic activity to be approved for the six major HCV genotypes (GT1–6). According to phase III trials SVR rates of more than 90% have been observed across all genotypes with only 12 weeks of SOF + PEG-INF + RBV in previously untreated adultsCitation11. Moreover, the INF-free SOF regimen provides a significant breakthrough for UI HCV patients who previously had no effective treatment alternatives. The recently published EASL clinical guidelines have recommended SOF as the preferred backbone treatment for all major genotypes of HCVCitation6.

Our analysis demonstrated that SOF-based regimens have a favorable cost-effectiveness profile compared to the treatments currently available for the six major HCV genotypes (GT1–6). SOF was also associated with considerable improvements in health outcomes and long-term complications across all genotypes and patient populations studied in this analysis. An investigation of QALYs shows that the SOF-based regimens were associated with gains for patients across all genotypes particularly in UI and in cirrhotic patients.

For the analysis with approximately 20% of the patients initiating treatment in the compensated cirrhosis stage, the SOF-based regimens are cost-effective for almost all populations, with ICERs ranging from €13,233/QALY to about €37,334/QALY. The two exceptions were observed in GT1 TE IE (versus telaprevir) and in GT2 TN IE patients for whom the ICERs for the mixed cohort were higher than €40,000/QALY (€58,700 and €68,500/QALY). However, even when compared to PEG-IFN + RBV, the SOF regimen becomes cost-effective for cirrhotic patients (€22,078 and €28,490 respectively). Probabilistic sensitivity analyses showed that most of the simulations were below €40,000/QALY, thus confirming the robustness of those results. It is also worth mentioning that GT2 TN IE patients account for a small proportion of all HCV patients in Italy. Besides the fact that, overall, GT2 only accounts for 17% of Italian HCV patients, available data show that only 22% of those have never been treated beforeCitation6.

The INF-free SOF regimen offers the first treatment option for UI patients. The regimen was found to be extremely efficacious and was associated with high 12 week SVRs of 95% and 93% in TN UI GT2 patients with and without cirrhosis, respectively. Similar results were also observed in TN UI GT3 patients with 24 week SVRs of 92% and 94% for patients with and without cirrhosis, respectively. In addition, our analyses also suggest that the regimen is cost-effective in GT2 and GT3 patients, compared to the current standard of care, with ICERs significantly below the threshold of €40,000/QALY. In TN UI GT1 the ICER comparing the SOF regimen versus no treatment was slightly higher but still below the threshold at €31,393/QALY. The 24 week SVRs for the SOF regimen were lower in this population, 36% and 68% for patients with and without cirrhosis, respectively.

Our analysis demonstrated that for nearly all indications the ICERs/QALY for the mixed cohort were below €40,000/QALY, a threshold that is generally considered cost-effective in Italy. The model also showed that for cirrhotic patients the SOF regimen is very cost-effective in all genotypes (GT1-6) with an ICER as low as €5828/QALY in GT2 TN UI. In addition cost-effectiveness was observed in hard-to-treat TE patients. Our study also demonstrates that in TE UI GT2 and GT3 patients the SOF-based regimen is cost-effective compared with current standard of care ().

Figure 3. ICERs by patient population versus HCV prevalence by genotype. TEL, Telaprevir; BOC, Boceprevir; PR, Peginterferon alfa + ribavirin; NT, No treatment; IE, Interferon eligible; UI, Unsuitable for interferon; SOF, Sofosbuvir; RBV, Ribavirin; HCV, Hepatitis C virus.

The cost-effectiveness of SOF among TE GT1 patients was also included in our study. Superior SVR rates for SOF + PEG-INF (12 weeks) have been observed for this patient population compared to telaprevir, boceprevir and PEG-INF + RBV resulting in ICERs below €40,000/QALY against boceprevir and PEG-INF + RBV and for cirrhotic patients. Therefore, a reduction in the economic and health burden of the disease is to be expected due to the increasing number of SVR-achieving patients and a decrease in complications such as HCC, CC, DC and LT.

Our analysis has several strengths. The model structure developed for this analysis presents the natural course of the disease and is also consistent with the study design of the pivotal phase III clinical trials of SOF that randomized patients based on whether they were cirrhotic or non-cirrhotic. In order to ensure the model was representative of the Italian patient population, the demographic characteristics for all the genotypes were obtained from the PROBE studyCitation17.

Limitations are present in this study. Firstly, the literature was lacking in data to populate the SVRs in the model for the ‘non-cirrhotic’ and ‘cirrhotic’ health states, specifically for the TE GT2/3 patients. The selection of SVRs for the model is therefore likely to favor the comparator rather than SOF. Secondly, we used the ex-factory price for SOF while NHS hospitals prices for the comparators, which is also in favor of the comparators rather than SOF. In addition, the potential drug wastage of a PEG-INF regimen was not accounted for in the analysis. Consequently, the comparator regimens are assumed to have lower pharmacological costs. We adopted the perspective of the Italian NHS and therefore indirect costs were not included. Given that SOF prevents productivity losses from sick leave due to more advanced stages of the disease SOF would be even more cost-effective from a societal perspective. In addition we did not account for hospitalizations related to adverse events due to PI, therefore underestimating the cost of PI treatment. It should also be noted that the model did not consider decompensated cirrhosis and pre-transplant populations, where SOF based regimens could potentially avoid transplantation. Also the model did not include the costs associated with extra-hepatic complications in HCV such as diabetes and kidney failure. The potential reduction in future HCV infections following successful treatment of the infection were not considered in the model. However, as higher SVRs were associated with SOF compared to the current standard of care across the genotypes, this would lead to the benefits related to reduced economic and health burden being higher for the SOF-based regimens. Finally, the analysis did not include the regimens recently approved by the FDA and the EMA such as ledipasvir/sofosbuvir, simeprevir, daclatasvir and ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir + dasabuvir since they were not approved in Italy at the time of the analysis. Further analysis should be conducted to include these treatments once price and reimbursement are defined.

A cost-effectiveness analysis of sofosbuvir versus telaprevir and boceprevir in GT1 patients in Italy has recently been published by Petta et al.Citation33. However it was difficult to compare both analyses due to their input data for efficacy, safety, transition probabilities, utilities and costs being different to those included in our model. A study by Leleu et al.Citation34 assessed the cost-effectiveness of co-infected and mono-infected patients in France. While the structure is similar to our model, the input data is different. First, the proportion of cirrhotic patients is higher in this model. Second, the utility values associated with the more advanced health states are higher in the French model and only one utility decrement was considered for sofosbuvir. In our model the utility decrements for SOF came from the different trials. Third, the costs of CC and DCC, HCC and LT are substantially different from those in Italy. Finally a combined ICER for all patient populations was presented but no details were provided on how this was estimated. Nevertheless the authors also concluded that SOF is a cost-effective regimen.

In another cost-effectiveness study in GT1 TN patients in France, Deuffic-Burban et al.Citation35 concluded that SOF + PEG-INF + RBV was cost-effective for patients with METAVIR score F2 and above. Similar conclusions were obtained by the analysis by San MR et al.Citation36 that evaluated the cost-effectiveness of SOF regimens in GT1 to GT3 patients from the perspective of the Spanish National Public Healthcare System. Finally, a cost-effectiveness study in the USCitation37 concluded that SOF + PEG-INF + RBV given for 12 weeks is generally less costly and more effective than the interferon-based regimens telaprevir, boceprevir and simeprevir.

Conclusion

SOF-based regimens are a cost-effective alternative to the current standard of care for HCV infection in Italy. For patients with hepatitis C, particularly those not eligible for, or able to tolerate, current INF-based regimens, SOF provides a new realistic alternative for a successful HCV cure.

SOF provides a shorter, well tolerated and effective anti-viral treatment. The combination of superior SVR rates and the ability to treat a wider variety of patient populations gives SOF the potential to reduce the long-term disease and economic burden of HCV infection to the Italian public health system. Finally, in the recently published guidelines by EASL they recommend SOF as the preferred backbone treatment for all major genotypes of HCV.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was funded by Gilead Sciences.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

S.C. and I.G. have disclosed that they have received consulting fees from Gilead. C.C. has disclosed that she has received consulting fees from Gilead, MSD, Janssen-cilag, Roche and Bayer. A.C. has disclosed that he has received consulting fees from Abbvie, Gilead, Janssen-cilag, Achilleon, Roche, MSD, Bristol Myers Squibb and Böhringer-Ingelheim. G.C. has disclosed that he has received consulting fees from Bristol Myers Squibb, ViiV Healthcare, MSD, Abbvie, Janssen Cilag and Gilead.

JME peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Supplemental Material.pdf

Download PDF (35.3 KB)Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Elisa Martelli and Rowena Holland for their contribution to the study.

References

- Chen SL, Morgan TR. The natural history of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. Int J Med Sci 2006;3:47-52

- Torre GL, Gualano MR, Semyonov L et al. Hepatitis C virus infections trends in Italy, 1996–2006. Hepat Mon 2011;11:895-900

- Cornberg M, Razavi HA, Alberti A et al. A systematic review of hepatitis C virus epidemiology in Europe, Canada and Israel. Liver International 2011;31:30-60

- Ciampichini R, Scalone L, Fagiuoli S, et al. Societal burden in hepatitis C patients: the come study results. Value in Health Conference: 17th Annual International Meeting of the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research, ISPOR, 2 June 2012, Washington, DC, USA

- Mennini FS. Il costo dell'epatite C. WEF, 2012. Facoltá di Economia, Universitá di Roma Tor Vergata and Kingston Business School, Kingston University, London, UK

- EASL (European Association for the Study of the Liver). EASL Recommendations on Treatment of Hepatitis C. 2014. http://files.easl.eu/easl-recommendations-on-treatment-of-hepatitis-C.pdf [last accessed 30 January 2015]

- Therapy KnowlEdge HCV di Edge Consulting srl., 2014

- North CS, Hong BA, Adewuyi SA, et al. Hepatitis C treatment and SVR: the gap between clinical trials and real-world treatment aspirations. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2013;35:122-8

- Falck-Ytter Y, Kale H, Mullen KD, et al. Surprisingly small effect of antiviral treatment in patients with hepatitis C. Ann Intern Med 2002;136:288-92

- Belperio PS, Hwang EW, Thomas IC, et al. Early virologic responses and hematologic safety of direct-acting antiviral therapies in veterans with chronic hepatitis C. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013;11:1021-7

- Shah N, Pierce T, Kowdley KV. Review of direct-acting antiviral agents for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2013;22:1107-21

- EMA. Sovaldi Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC). 2014. Available at: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/002798/WC500160597.pdf [last accessed 30 January 2015]

- EASL. Clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatitis C virus infection. J Hepatol 2014;60:392-420

- Shepherd J, Jones J, Hartwell D et al. Interferon alfa (pegylated and non-pegylated) and ribavirin for the treatment of mild chronic hepatitis C: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess 2007;11:1-224

- Hartwell D, Jones J, Baxter L, et al. Peginterferon alfa and ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C in patients eligible for shortened treatment, re-treatment or in HCV/HIV co-infection: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess 2011;15:i-210

- Chen J, Florian J, Carter W, et al. Earlier sustained virologic response end points for regulatory approval and dose selection of hepatitis C therapies. Gastroenterology 2013;144:1450-5

- Fattore G. Proposta di linee guida per la valutazione economica degli interventi sanitari in Italia. Pharmacoeconomics Ital Res Articles 2009;11:83-93

- Craxi A, Piccinino F, Ciancio A, et al. Real-world outcomes in patients with chronic hepatitis C: primary results of the PROBE study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;26:388-95

- McLauchlan J. Query of 5000 anonymised patient records performed October 2013. HCV UK Research Database, 2013

- Associazione italiana per lo studio del fegato. 2011. Available at: http://www.webaisf.org/ [last accessed 30 January 2015]

- Bacon B, Dieterich D, Flamm S, et al. Efficacy of sofosbuvir and simeprevir-based regimens for HCV treatment-experienced GT1 patients in a real-life setting; data from the TRIO network. 65th Annual Meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, 7 November 2014, Boston, MA, USA

- EMA. Incivo Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC). 2014. Available at: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/002313/WC500115529.pdf [last accessed 30 January 2015]

- EMA. Victrelis Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC). 2014. Available at: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/002332/WC500109786.pdf [last accessed 30 January 2015]

- Grishchenko M, Grieve RD, Sweeting MJ, et al. Cost-effectiveness of pegylated interferon and ribavirin for patients with chronic hepatitis C treated in routine clinical practice. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2009;25:171-80

- Istituto nazionale di statistica. 2012. Available at: http://www.istat.it/it/istituto-nazionale-di-statistica [last accessed 30 January 2015]

- Wright M, Grieve R, Roberts J, et al. Health benefits of antiviral therapy for mild chronic hepatitis C: randomised controlled trial and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess 2006;10:1-113, iii

- Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Henry L, et al. Minimal impact of sofosbuvir and ribavirin on health related quality of life in chronic hepatitis C (CH-C). J Hepatol 2014;60:741-7

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Telaprevir for the treatment of genotype 1 chronic hepatitis C – NICE technology appraisal guidance 252. 2012. http://www.google.com/url?url=http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta252/resources/guidance-telaprevir-for-the-treatment-of-genotype-1-chronic-hepatitis-c-pdf&rct=j&frm=1&q=&esrc=s&sa=U&ei=gtg0VbGEEJGxogSA8oGoCg&ved=0CBQQFjAA&usg=AFQjCNGNJVJwQ8VpskiuxEmm8Lx9__YHWA [last accessed 30 January 2015]

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Boceprevir for the treatment of genotype 1 chronic hepatitis C – NICE technology appraisal guidance 253. 2012. https://www.google.com/url?url=https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta253/resources/guidance-boceprevir-for-the-treatment-of-genotype1-chronic-hepatitisc-pdf&rct=j&frm=1&q=&esrc=s&sa=U&ei=udg0VYXZMoG3ogSS-YCoCQ&ved=0CBQQFjAA&usg=AFQjCNGFzlFb8l_IvkzCpDcKtd-2oAL2IQ [last accessed 30 January 2015]

- Brazier J, Roberts J, Deverill M. The estimation of a preference-based measure of health from the SF-36. J Health Econ 2002;21:271-92

- Gray AM, Rivero-Arias O, Clarke PM. Estimating the association between SF-12 responses and EQ-5D utility values by response mapping. Med Decis Making 2006;26:18-29

- Remunerazione delle prestazioni di assistenza ospedaliera per acuti, assistenza ospedaliera di riabilitazione e di lungodegenza post acuzie e di assistenza specialistica ambulatoriale. Supplemento ordinario alla ‘Gazzetta Ufficiale' n. 23 del 28 gennaio 2013 – Serie generale. DM, 2012. http://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2013/01/28/13A00528/sg

- Petta S, Cabibbo G, Enea M, et al. Cost-effectiveness of sofosbuvir-based triple therapy for untreated patients with genotype 1 chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology 2014;59:1692-705

- Leleu H, Blachier M, Rosa I. Cost-effectiveness of sofosbuvir in the treatment of patients with hepatitis C. J Viral Hepat 2015;22:376-83

- Deuffic-Burban S, Schwarzinger M, Obach D, et al. Should we await IFN-free regimens to treat HCV genotype 1 treatment-naive patients? A cost-effectiveness analysis (ANRS 95141). J Hepatol 2014;61:7-14

- San MR, Gimeno-Ballester V, Blazquez A, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of sofosbuvir-based regimens for chronic hepatitis C. Gut 2014. pii: gutjnl-2014-307772. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-307772. [Epub ahead of print]

- Saab S, Gordon SC, Park H, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of sofosbuvir plus peginterferon/ribavirin in the treatment of chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014;40:657-75

- Lawitz E, Zeuzem S, Nyberg L, et al. Boceprevir (BOC) Combined with Peginterferon alfa-2b/Ribavirin (P/RBV) in Treatment-Naïve Chronic HCV Genotype 1 Patients with Compensated Cirrhosis: Sustained Virologic Response (SVR) and Safety Subanalyses from the Anemia Management Study, Abstract 50. Boston, MA: AASLD, 9–12 November 2012

- McHutchison JG, Lawitz EJ, Shiffman ML, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2b or alfa-2a with ribavirin for treatment of hepatitis C infection. N Engl J Med 2009;361:580-93

- Lagging M, Rembeck K, Rauning BM, et al. Retreatment with peg-interferon and ribavirin in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 2 or 3 infection with prior relapse. Scand J Gastroenterol 2013;48:839-47

- Shoeb D, Rowe IA, Freshwater D, et al. Response to antiviral therapy in patients with genotype 3 chronic hepatitis C: fibrosis but not race encourages relapse. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011;23:747-53

- Manns MP, McHutchison JG, Gordon SC, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin compared with interferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C: a randomised trial. Lancet 2001;358:958-65

- Thomson BJ, Kwong G, Ratib S, et al. Response rates to combination therapy for chronic HCV infection in a clinical setting and derivation of probability tables for individual patient management. J Viral Hepat 2008;15:271-8

- Fattovich G, Giustina G, Degos F, et al. Morbidity and mortality in compensated cirrhosis type C: a retrospective follow-up study of 384 patients. Gastroenterology 1997;112:463-72