Abstract

Objective:

Selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are widely prescribed antidepressants. This claims database study compared healthcare resource use and costs among patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) treated with vilazodone vs other SSRIs.

Methods:

Adults with an MDD diagnosis and ≥1 prescription fill for vilazodone, citalopram, escitalopram, fluoxetine, paroxetine, or sertraline were identified from administrative claims data (2010–2012). Patients who concomitantly used adjunctive medication, either a second-generation antidepressant or antipsychotic, were excluded. All-cause and MDD-related healthcare resource use and costs (in 2012 USD) were compared between patients treated with vilazodone vs other SSRIs over a 6-month follow-up period using unadjusted and multivariable analyses.

Results:

The study cohort included 49 861 patients (mean age = 44.0 years; 70% female). Compared with the vilazodone cohort (n = 3527), patients in the citalopram (n = 12 187), escitalopram (n = 8275), fluoxetine (n = 10 142), paroxetine (n = 3146), and sertraline (n = 12 584) cohorts had significantly more all-cause inpatient hospital visits, longer hospital stays and more frequent emergency department visits, following the index date, after adjusting for baseline characteristics. All-cause medical service costs (inpatient + outpatient + emergency department visits) were significantly higher across all other SSRI cohorts vs vilazodone by $758–$1165 (p < 0.05). Similarly, all-cause total costs, were significantly or numerically (non-significantly) higher across all SSRI cohorts vs vilazodone by $351–$780.

Limitations:

The was no clinical measurement of disease severity, partial coverage of the Medicare-eligible population, and short follow-up.

Conclusion:

MDD treatment with vilazodone was associated with significantly lower rates of inpatient and emergency services, and with significantly lower all-cause medical service costs and numerically (non-significantly) lower total costs to payers than with the other SSRIs included in this study.

Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is one of the most common mental health disorders, with a lifetime prevalence of 13–16%, which translates into 35 million affected adults in the USCitation1,Citation2. It is among the leading causes of disability worldwideCitation3–5, and has the greatest impact on health-related quality-of-life (HRQoL) among chronic diseasesCitation6. The economic burden associated with MDD is also substantial. The overall annual cost of MDD in the US reached $210.5 billion in 2010 (reported in 2012 USD)Citation7. The total 2-year cost of MDD was calculated at $20 976 per patient (in 2007 USD) for patients responding to therapy and at $32 537 for patients not responding adequately to therapyCitation8. However, with appropriate treatment, patients experience not only relief in symptomsCitation9,Citation10, but a decrease in the economic and other burdens of the disease, such as improvement in quality-of-lifeCitation9,Citation11, productivityCitation12, and lower healthcare costsCitation8,Citation13,Citation14.

Current treatments for MDD include psychotherapy, pharmacological treatment, or a combination of bothCitation15,Citation16. While medications for the treatment of MDD comprise a broad range of agents – selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin and norepinephrine re-uptake inhibitors (SNRIs), atypical antidepressants, tricyclic and tetracyclic antidepressants, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, second-generation/atypical anti-psychoticsCitation15,Citation16 – ∼63–90% of patients with MDDCitation17–20 are treated with SSRIsCitation21. The popularity of SSRIs is mainly due to their generally acceptable safety and tolerability profiles and their efficacy in treating MDD, compared to older antidepressantsCitation22–25. However, while SSRIs are effective for a large number of patients with MDD, nearly 60% of patients historically do not achieve remission with these medicationsCitation26–29 or relapse after some period of time on treatmentCitation27. SNRIs are frequently the second-line agent of choice in patients who have not responded or are intolerant to SSRIsCitation30,Citation31, although debate exists whether an SNRI or a different SSRI is best in this caseCitation32–35.

Current drug research strategies have sought to selectively target or augment the response of specific neurotransmitter pathways while building on the proven basic pharmacological profile of older agentsCitation36,Citation37. Vilazodone, approved in 2011 in the US for the treatment of MDD in adultsCitation38, exhibits a dual mechanism of actionCitation39–41 that combines the inhibition of serotonin re-uptake transporters with partial agonist activity at serotonin-1A (5-HT1A) receptorsCitation42,Citation43. In two 8-week phase III clinical trials (NCT00683592Citation44,Citation45, NCT00285376Citation46,Citation47), a 1-year open-label phase III trial (NCT00644358Citation42,Citation45), and two phase IV trials (NCT01473381Citation48, NCT01473394Citation49,Citation50), vilazodone was found to be effective and generally well tolerated in adults with MDDCitation51,Citation52. Although the net effect of 5-HT1A receptor partial agonist on serotonergic transmission is not yet known, some evidence from clinical and pre-clinical studies suggests that activating 5-HT1A receptors may enhance antidepressant efficacy by improving time to onset of action, and may also reduce the risk of experiencing sexual dysfunction, a side-effect associated with some SSRIsCitation44,Citation45,Citation52–54.

Due to its recent introduction into clinical practice, the economic outcomes of vilazodone treatment relative to other SSRI therapies have not yet been investigated. However, this information is important to physicians in determining the optimal treatment choice for their patients; to payers, in evaluating the comparative effectiveness of available antidepressant treatments; and to the greater society, in terms of health policy – making informed decisions on resource allocation for the treatment of the disease. Thus, the current retrospective observational study assessed healthcare resource utilization and costs among adult patients with MDD treated with vilazodone vs other SSRIs (citalopram, escitalopram, fluoxetine, paroxetine, and sertraline) using real-world administrative claims data.

Methods

Data source

Data were extracted from the Truven Health Analytics MarketScan® database (January 1, 2010 to December 31, 2012) – a private insurance database which reflects the healthcare experience of employees and dependents covered by the health benefit programs of large employers. Medicare-eligible retirees with employer-provided Medicare Supplemental plans are also included in this database. Data are collected from ∼100 different insurance companies. The database includes enrollment history and claims for medical and pharmacy services. Data are de-identified, comply with the patient confidentiality requirements of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, and are exempt from institutional review board approval.

Sample selection

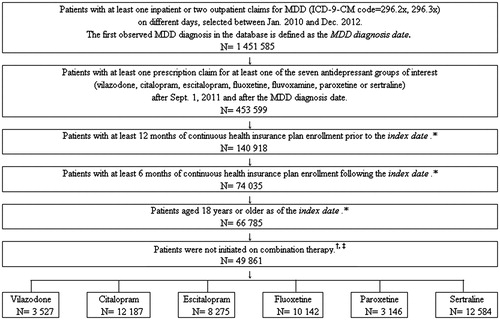

Adult patients with MDD were selected for the study if they had at least one inpatient or two outpatient claims for the diagnosis code of MDD on different days (International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM] code: 296.2x or 296.3x) between January 2010 and December 2012, where the first observed MDD diagnosis in the database was defined as the MDD diagnosis date. Patients were further required to have at least one prescription claim for at least one of the seven antidepressants (i.e., vilazodone, citalopram, escitalopram, fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, or fluvoxamine) filled after the MDD diagnosis date, between September 1, 2011 and December 31, 2012. The date of the earliest prescription claim for any of the seven antidepressants, whichever occurred first, was defined as the index date, and the antidepressant filled on that date was defined as the index drug. A washout period (during which patients did not use the index drug) of 12 months prior to the index date was required for each eligible patient. Additionally, patients were at least 18 years old of age at the index date and had at least 12 months of continuous enrollment in the health insurance plan without a prescription fill for the index drug prior to the index date (baseline period and washout period) and at least 6 months of continuous enrollment in the health insurance plan following the index date (study period). Furthermore, patients were selected for the study only if they were not initiated on any combination therapy (i.e., did not use or augment with a second second-generation antidepressant or antipsychotic other than index drug within 2 weeks after the index date; second-generation antidepressants included SSRIs, SNRIs, bupropion, nefazodone, trazodone, and mirtazapine). For all analyses, patients were classified into one of the six treatment groups (vilazodone, citalopram, escitalopram, fluoxetine, paroxetine, or sertraline) based on the index drug received. Patients receiving fluvoxamine as the index drug were excluded from the following analysis due to small sample size.

Patient characteristics

Patient characteristics – demographics, insurance type, comorbidities (Charlson comorbidity index [CCI] score, selected comorbiditiesCitation8, see Supplementary Appendix A for detailed code information of the comorbidities included in the study), antidepressant treatment (see Supplementary Appendix B for a list of GPI codes used to identify prior treatment), pharmacy copayment, and healthcare resource use and costs – were measured during the baseline period.

Outcome measures

Healthcare resource utilization – number of hospitalizations, length of hospital stay (days), number of emergency department (ED) visits, and number of outpatient visits – was assessed during the study period for each study cohort. Both all-cause and MDD-related utilization was evaluated. Medical visits were considered MDD-related if they were associated with a primary or secondary MDD diagnosis (ICD-9 CM code: 296.2x or 296.3x).

Healthcare costs were measured during the study period and calculated for each study cohort. MDD-related healthcare costs included all costs paid for an MDD-related medical visit. Pharmacy costs for second generation antidepressants were considered MDD-related. All-cause and MDD-related healthcare costs, including inpatient, emergency department (ED), outpatient, pharmacy, medical service (inpatient + ED + outpatient costs), and total healthcare costs (medical service + pharmacy costs), were calculated for each cohort.

All costs were measured from a payer’s perspective and adjusted for inflationCitation55 to 2012 USD.

Statistical analyses

Patient baseline characteristics were compared between vilazodone and each of the other SSRI cohorts using Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for continuous variables and Chi-squared tests for categorical variables. Unadjusted healthcare resource utilization was summarized as incidence rates and average healthcare costs. Healthcare resource utilization was compared between each SSRI treatment group and vilazodone using adjusted Poisson regression models with robust standard errors. Results were reported as adjusted incidence rate ratios (IRRs) with their respective 95% confidence intervals and p-values. Healthcare costs were compared between vilazodone and SSRI cohorts using generalized linear regression models with robust standard errors, and results were reported as adjusted mean cost differences. All multivariable models were adjusted for age, gender, insurance type, index year, comorbidities, antidepressant treatment, and pharmacy copay at baseline.

All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS Version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). A two-sided alpha error of 0.05 indicated statistical significance.

Results

Study sample and patient baseline characteristics

The study cohort included 49 861 patients with a diagnosis of MDD: 3527 were treated with vilazodone, 12 187 with citalopram, 8275 with escitalopram, 10 142 with fluoxetine, 3146 with paroxetine, and 12 584 with sertraline (). The mean patient age was 44.0 years and 70% were female (data not shown); however, patients in the vilazodone group were significantly older than patients in all other treatment groups (46.5 years old vs 42.4–45.0, p < 0.05) (). Patients’ CCI score ranged from 0.51–0.67; vilazodone-treated patients had a significantly lower CCI (0.54) than patients who were taking citalopram or paroxetine (0.66–0.67, p < 0.01). Several comorbidities were more common during the baseline period in the vilazodone cohort compared to other SSRIs: bipolar disorder (13.8% vs 8.3–10.8%, p < 0.001), sleep disorder (10.0% vs 7.7–7.8%, p < 0.001, with the exception of paroxetine), sexual dysfunction (2.9% vs 1.7–2.1%, p < 0.05), fibromyalgia (8.9% vs 5.8–7.0%, p < 0.001), and hyperlipidemia (30.1% vs 21.0–25.8%, p < 0.001).

Figure 1. Sample selection flowchart for patients with MDD treated with vilazodone or other SSRIs between 2010 and 2012. * The date of the earliest prescription claim on or after September 1, 2011, for citalopram, escitalopram, fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, or vilazodone, whichever occurred first, was defined as the index date (with a 12-month wash-out period prior), and the antidepressant filled on that date was defined as the index drug. † Patients did not use any second-generation antidepressant or antipsychotic other than the index drug within 2 weeks after the index date. Second-generation antidepressants included SSRIs, SNRIs, bupropion, nefazodone, trazodone, and mirtazapine. ‡ Patients receiving fluvoxamine as the index drug were excluded from the analysis due to small sample size. MDD, major depressive disorder; SNRI, serotonin and norepinephrine re-uptake inhibitor; SSRI, selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitor.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of patients treated with vilazodone vs other SSRIs†,‡.

During the baseline period, patients in the vilazodone group had more prior treatments with antidepressants than patients in other SSRI cohorts (p < 0.001) (). Patients in the vilazodone group incurred higher pharmacy costs than other treatment groups in the same period ($4362 vs $2006–$2382, p < 0.001). Total costs were also higher for vilazodone patients than for patients on other SSRIs during the baseline period ($14 166 vs $10 961–$12 173, p < 0.001).

Healthcare resource utilization during study period

Vilazodone users had fewer hospitalizations than other SSRI users. The mean number of all-cause hospitalizations during the 6-month period after the index date was 9.9 per 100 patients – lower than the incidence rates for the other treatment groups (13.2–17. 1 per 100 patients) (). Moreover, hospital stays were shorter for patients taking vilazodone than those taking other SSRIs (64.1 days vs 79.3–110.3 days per 100 patients). Similar findings were noted for MDD-related hospitalizations (). However, vilazodone users had more outpatient visits during the 6-month study period than other SSRI users: all-cause outpatient visits occurred at a rate of 1539.9 per 100 patients in the vilazodone group, compared to 1330.1–1487.2 per 100 patients for all other SSRI cohorts. Similarly, MDD-related outpatient visits were more frequent in the vilazodone group compared to all other cohorts.

Table 2. Comparison of 6-month healthcare resource utilization between SSRIs and vilazodone; unadjusted incidence rates (per 100 patients).

After adjusting for differences in baseline characteristics, patients treated with vilazodone had significantly lower risk of hospitalization than those treated with other SSRIs, with IRRs for all other SSRIs vs vilazodone ranging from 1.48–1.70 for all-cause hospitalization, 1.50–1.68 for all-cause length of stay, and 1.50–1.79 for MDD-related hospitalization (all p < 0.001) (). Similarly, patients treated with vilazodone had significantly fewer ED visits than patients treated with other SSRIs: adjusted IRR for other treatment groups vs vilazodone ranged from 1.15–1.34 (p < 0.05 for all comparisons) ().

Table 3. Comparison of 6-month healthcare resource utilization between SSRIs and vilazodone; adjusted incidence rate ratios (95% CI) vs vilazodone†,‡.

Healthcare costs during study period

Consistent with hospital resource utilization trends, all-cause average inpatient costs for vilazodone during the 6-month study period were lower than those estimated for all other SSRI cohorts ($1532 vs $1546–$2027 per patient) (). All-cause average medical service costs for the vilazodone group were also lower than the costs incurred by all other SSRI cohorts ($4879 vs $4942–$5418 per patient), with the exception of the fluoxetine group ($4792 per patient).

Table 4. Comparison of 6-month healthcare costs between SSRIs and vilazodone; average healthcare costs (mean ± SD)†.

After adjusting for baseline characteristics, all-cause medical service costs were significantly higher across all other SSRI cohorts than for the vilazodone-treated group by $758–$1165 (p < 0.05 for all comparisons) (). Consistent with trends in resource utilization, the vilazodone group had an adjusted reduction in inpatient and outpatient costs of $303–$653 and of $287–$475, respectively, compared to the other SSRIs (). All-cause ED visit costs were lower (by $40–$82) in the vilazodone group than in all other SSRI groups (p < 0.001), with the exception of the escitalopram. However, pharmacy costs were higher for vilazodone-treated patients than for all other SSRIs, with the exception of escitalopram, both for all-cause and for MDD-related pharmacy costs: cost differences ranged from $383–$418 for all-cause pharmacy costs in favor of the other SSRI groups (p < 0.001); and from $264–$304 for MDD-related pharmacy costs (p < 0.001).

Table 5. Comparison of 6-month healthcare costs between SSRIs and vilazodone; adjusted difference in average healthcare costs (95% CI) vs vilazodone†,‡,$.

Discussion

This retrospective study used a large administrative claims database to assess healthcare resource utilization and costs for patients treated with vilazodone or with other SSRIs in a real-world clinical practice setting in order to understand how the use of vilazodone could impact patients with MDD. The results of this analysis show that vilazodone-treated patients had fewer hospitalizations and emergency department visits than patients treated with older SSRIs, but more outpatient visits. Costs reflected these differences in utilization, with all-cause medical service costs being lower in the vilazodone group compared to other SSRIs.

The comorbidity profiles and prior prescription patterns of the study cohorts seem to indicate that physicians may have prescribed vilazodone more frequently to older patients, or patients who had inadequate response to other medications (more previously-treated patients in the vilazodone group). Although the vilazodone-treated patients had lower inpatient and ED utilization during the study period, they had an increased number of outpatient visits compared to other SSRI cohorts. One possible explanation is that these patients may have one or more previous treatment failures, which necessitate more outpatient visits with their healthcare practitioner to facilitate treatment success. However, the use of inpatient and ED services remained significantly lower for the vilazodone-treated cohort than that of the other cohorts, which might suggest a decreased need for emergency care for the vilazodone cohort. This trend was previously observed in a real-world retrospective analysis of healthcare utilization patterns for escitalopram vs its parent compound, citalopramCitation56, and many economic evaluation studies reported higher cost-effectiveness of the newer SSRICitation57–62. Previous meta-analyses of clinical trial data, however, have not examined healthcare utilizations and costs for these compoundsCitation63,Citation64. Furthermore, patients enrolled in RCTs may have higher average adherence than those seen in the clinical office practice setting, and these adherence differences have been known to impact clinical effectiveness and economic outcomesCitation65–69.

Cost differences observed in this study were generally consistent with the observed utilization patterns: a trend of lower inpatient and ED service costs was noted for the vilazodone cohort compared to other SSRIs. After adjusting for baseline characteristics, medical service costs indicate significantly lower costs for the vilazodone group, and these were mainly due to lower costs for inpatient and ER outweighing increased pharmacy costs for the same groups. Pharmacy costs for vilazodone were higher than those for all other SSRIs except for escitalopram, because only these two medications did not have generic versions on the market until March 2012; and this difference is also reflected in the correspondingly higher MDD-related total costs for these two drugs compared to the remaining SSRIs. Previous claims analyses comparing other SSRIs have also found that inpatient costs are a major cost driver, where lower hospitalization rates can compensate for higher drug costsCitation56,Citation70. In the current analysis, even when pharmacy costs are taken into account, the vilazodone cohort still has lower total costs than other SSRIs, but the difference is no longer statistically significant. However, it is important to note that lower inpatient costs generally result in lower overall costs; moreover, a prior study has shown that further attempts to reduce costs by switching from branded medication to the generic version resulted in increased total costs (mainly due to increased medical service costs)Citation71.

A substantial portion of the differences in healthcare utilization and costs between the vilazodone and other SSRI groups was not MDD-related. MDD-related comorbidities may drive a portion of these costs, as a recent study has demonstrated that nearly 62% of the costs of MDD are not directly disease-relatedCitation7. Future research is warranted on the effect of candidate drugs on these MDD-associated comorbidities. Furthermore, as shown here and by others, it is important for future drug therapy assessments to focus on real-world healthcare utilization and cost considerations, as well as on clinical efficacy and safety, as demonstrated in clinical trial settings, when making patient care and policy decisions for the treatment of MDD.

The current study is subject to several limitations associated with insurance claims dataCitation72–74, including the potential introduction of errors or inaccuracies in the management of data, lack of detailed clinical information (such as disease severity, treatment history, symptom relief) in patients’ records, and generalizability limitations. While possible data or coding errors are unlikely to affect the treatment cohorts differentially, potential selection bias could exist in our study if patients in the comparator groups had different depression severity levels that could affect healthcare utilization in the study periodCitation56. To minimize this effect, only patients treated with SSRI monotherapy during the baseline period were included in the sample selection, and differences in important baseline characteristics were adjusted for in our multivariable analyses of healthcare utilization and cost differences among various SSRIs. Finally, the findings of this study are based on analysis of patients with private healthcare insurance and may not be generalizable to other populations (e.g., with public insurance coverage). Despite these limitations, this claims study reflects real-world economic outcomes in a large and representative sample of practice patternsCitation72–74.

Further limitations of the study may include possible cost under-estimates deriving from the use of partial coverage of the Medicare-eligible population in the current dataset and short follow-up duration. For patients over 65 years of age, if services are 100% covered by Medicare, the costs are not included in the MarketScan database. To evaluate how partial information could impact the main analysis, we conducted sensitivity analysis among patients aged 18–64 years; all sensitivity analysis findings were consistent with those of the main analysis (data not shown). Furthermore, the current study examined treatment utilization and costs for various SSRIs for a relatively short (6-month) follow-up period, thus it focuses only on short-term economic implications. Future research may be needed to assess the long-term and indirect costs of SSRI treatment in terms of effect on productivity and disability.

Conclusion

MDD treatment with vilazodone was associated with significantly lower rates of inpatient and emergency services, and with significantly lower all-cause medical service costs and numerically (non-significantly) lower total costs to payers, than treatment with other approved SSRIs included in the analysis. Vilazodone pharmacy costs were significantly higher than pharmacy costs for the other SSRIs included in this study and vilazodone patients had generally more outpatient visits than patients taking other SSRIs. Future research is warranted to evaluate the differences in real-world effectiveness that may be underlying these differences in economic outcomes.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This research was sponsored by Forest Research Institute, Inc., an affiliate of Actavis, Inc.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

SS is a current employee of Forest Research Institute, Inc., an affiliate of Actavis, Inc. ZYZ, PC (former employee), YZ (former employee), TT, and JS are employees of Analysis Group, Inc., which has received consultancy fees from Forest Research Institute, Inc., an affiliate of Actavis, Inc. JME peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgments

Medical writing assistance was provided by Ana Bozas, PhD, an employee of Analysis Group, Inc.

References

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). JAMA 2003;289:3095-105

- Hasin DS, Goodwin RD, Stinson FS, et al. Epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcoholism and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005;62:1097-106

- US Burden of Disease Collaborators. The State of US Health, 1990-2010: Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors. JAMA 2013;310:591-606 doi:10.1001/jama.2013.13805

- Whiteford HA, Degenhardt L, Rehm J, et al. Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2013;382:1575-86

- Ferrari AJ, Charlson FJ, Norman RE, et al. Burden of depressive disorders by country, sex, age, and year: findings from the global burden of disease study 2010. PLoS Med 2013;10:e1001547

- Moussavi S, Chatterji S, Verdes E, et al. Depression, chronic diseases, and decrements in health: results from the World Health Surveys. Lancet 2007;370:851-8

- Greenberg PE, Fournier A-A, Sisitsky T, et al. The economic burden of adults with major depressive disorder in the United States (2005 and 2010). J Clin Psychiatry 2015;76:155-62

- Ivanova JI, Birnbaum HG, Kidolezi Y, et al. Direct and indirect costs of employees with treatment-resistant and non-treatment-resistant major depressive disorder. Curr Med Res Opin 2010;26:2475-84

- IsHak WW, Mirocha J, Pi S, et al. Patient-reported outcomes before and after treatment of major depressive disorder. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2014;16:171-83

- Mrazek DA, Biernacka JM, McAlpine DE, et al. Treatment outcomes of depression: the pharmacogenomic research network antidepressant medication pharmacogenomic study. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2014;34:313-17

- IsHak WW, Greenberg JM, Balayan K, et al. Quality of life: the ultimate outcome measure of interventions in major depressive disorder. Harv Rev Psychiatry 2011;19:229-39

- Woo J-M, Kim W, Hwang T-Y, et al. Impact of depression on work productivity and its improvement after outpatient treatment with antidepressants. Value Health 2011;14:475-82

- Tournier M, Crott R, Gaudron Y, et al. Economic impact of antidepressant treatment duration in naturalistic conditions. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2013;127:365-72

- Pan Y-J, Knapp M, McCrone P. Impact of initial treatment outcome on long-term costs of depression: a 3-year nationwide follow-up study in Taiwan. Psychol Med 2014;44:1147-58

- Davidson JRT. Major depressive disorder treatment guidelines in America and Europe. J Clin Psychiatry 2010;71(E Suppl):e04

- Nutt DJ, Davidson JRT, Gelenberg AJ, et al. International consensus statement on major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2010;71(E Suppl):e08

- Uchida N, Chong M-Y, Tan CH, et al. International study on antidepressant prescription pattern at 20 teaching hospitals and major psychiatric institutions in East Asia: analysis of 1898 cases from China, Japan, Korea, Singapore and Taiwan. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2007;61:522-8

- Exeter D, Robinson E, Wheeler A. Antidepressant dispensing trends in New Zealand between 2004 and 2007. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2009;43:1131-40

- Bauer M, Monz BU, Montejo AL, et al. Prescribing patterns of antidepressants in Europe: results from the Factors Influencing Depression Endpoints Research (FINDER) study. Eur Psychiatry 2008;23:66-73

- Ornstein S, Stuart G, Jenkins R. Depression diagnoses and antidepressant use in primary care practices: a study from the Practice Partner Research Network (PPRNet). J Fam Pract 2000;49:68-72

- Lin H-C, Erickson SR, Balkrishnan R. Physician prescribing patterns of innovative antidepressants in the United States: the case of MDD patients 1993-2007. Int J Psychiatry Med 2011;42:353-68

- Schatzberg AF. Safety and tolerability of antidepressants: weighing the impact on treatment decisions. J Clin Psychiatry 2007;68(8 Suppl):26-34

- Anderson IM. Meta-analytical studies on new antidepressants. Br Med Bull 2001;57:161-78

- Koenig AM, Thase ME. First-line pharmacotherapies for depression - what is the best choice? Pol Arch Med Wewnętrznej 2009;119:478-86

- Valuck R. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: a class review. Pharm Ther 2004;29:234-43

- Warden D, Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, et al. The STAR*D project results: a comprehensive review of findings. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2007;9:449-59

- Huynh NN, McIntyre RS. What are the implications of the STAR*D trial for primary care? A review and synthesis. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 2008;10:91-6

- Thase ME, Nierenberg AA, Vrijland P, et al. Remission with mirtazapine and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from 15 controlled trials of acute phase treatment of major depression. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2010;25:189-98

- Machado M, Einarson TR. Comparison of SSRIs and SNRIs in major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of head-to-head randomized clinical trials. J Clin Pharm Ther 2010;35:177-88

- Thase M, Connolly KR. Unipolar depression in adults: treatment of resistant depression. In: Roy-Byrne PP, ed. Waltham, MA: Wolters Kluwer Health; 2015. Available at: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/unipolar-depression-in-adults-treatment-of-resistant-depression. Accessed May 19, 2015

- Taylor D, Lenox-Smith A, Bradley A. A review of the suitability of duloxetine and venlafaxine for use in patients with depression in primary care with a focus on cardiovascular safety, suicide and mortality due to antidepressant overdose. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol 2013;3:151-61

- Papakostas GI, Fava M, Thase ME. Treatment of SSRI-resistant depression: a meta-analysis comparing within- versus across-class switches. Biol Psychiatry 2008;63:699-704

- Lam RW, Lönn SL, Despiégel N. Escitalopram versus serotonin noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors as second step treatment for patients with major depressive disorder: a pooled analysis. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2010;25:199-203

- Signorovitch J, Ramakrishnan K, Ben-Hamadi R, et al. Remission of major depressive disorder without adverse events: a comparison of escitalopram versus serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors. Curr Med Res Opin 2011;27:1089-96

- Santaguida P (Lina), MacQueen G, Keshavarz H, et al. Treatment for depression after unsatisfactory response to SSRIs. Comparative Effectiveness Reviews, No. 62. McMaster University Evidence-based Practice Center Report No.: 12-EHC050-EF. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2012 Apr. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/PMH0046379/. Accessed May 19, 2015

- Millan MJ. Multi-target strategies for the improved treatment of depressive states: conceptual foundations and neuronal substrates, drug discovery and therapeutic application. Pharmacol Ther 2006;110:135-370

- Connolly KR, Thase ME. Emerging drugs for major depressive disorder. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs 2012;17:105-26

- Forest Labs Inc. Vilazodone. Silver Spring, MD: U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2011. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2011/022567s000ltr.pdf. Accessed November 8, 2014

- Watson JM, Dawson LA. Characterization of the potent 5-HT(1A/B) receptor antagonist and serotonin reuptake inhibitor SB-649915: preclinical evidence for hastened onset of antidepressant/anxiolytic efficacy. CNS Drug Rev 2007;13:206-23

- Hughes ZA, Starr KR, Langmead CJ, et al. Neurochemical evaluation of the novel 5-HT1A receptor partial agonist/serotonin reuptake inhibitor, vilazodone. Eur J Pharmacol 2005;510:49-57

- Ashby CR, Kehne JH, Bartoszyk GD, et al. Electrophysiological evidence for rapid 5-HT1A autoreceptor inhibition by vilazodone, a 5-HT1A receptor partial agonist and 5-HT reuptake inhibitor. Eur J Pharmacol 2013;714:359-65

- Robinson DS, Kajdasz DK, Gallipoli S, et al. A 1-year, open-label study assessing the safety and tolerability of vilazodone in patients with major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2011;31:643-6

- Pierz KA, Thase ME. A review of vilazodone, serotonin, and major depressive disorder. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2014;16:e1-e8

- Jain R, Chen D, Edwards J, et al. Early and sustained improvement with vilazodone in adult patients with major depressive disorder: post hoc analyses of two phase III trials. Curr Med Res Opin 2014;30:263-70

- Clayton AH, Kennedy SH, Edwards JB, et al. The effect of vilazodone on sexual function during the treatment of major depressive disorder. J Sex Med 2013;10:2465-76

- Rickels K, Athanasiou M, Robinson DS, et al. Evidence for efficacy and tolerability of vilazodone in the treatment of major depressive disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry 2009;70:326-33

- Khan A, Sambunaris A, Edwards J, et al. Vilazodone in the treatment of major depressive disorder: efficacy across symptoms and severity of depression. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2014;29:86-92

- Mathews M, Gommoll C, Chen D, et al. Efficacy and safety of vilazodone 20 and 40 mg in major depressive disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2015;30:67-74

- Citrome L, Gommoll CP, Tang X, et al. Evaluating the efficacy of vilazodone in achieving remission in patients with major depressive disorder: post-hoc analyses of a phase IV trial. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2015;30:75-81

- Croft HA, Pomara N, Gommoll C, et al. Efficacy and safety of vilazodone in major depressive disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry 2014;75:e1291-8

- Wang S-M, Han C, Lee S-J, et al. A review of current evidence for vilazodone in major depressive disorder. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract 2013;17:160-9

- Citrome L. Vilazodone for major depressive disorder: a systematic review of the efficacy and safety profile for this newly approved antidepressant - what is the number needed to treat, number needed to harm and likelihood to be helped or harmed? Int J Clin Pract 2012;66:356-68

- Dawson LA. The discovery and development of vilazodone for the treatment of depression: a novel antidepressant or simply another SSRI? Expert Opin Drug Discov 2013;8:1529-39

- Deardorff WJ, Grossberg GT. A review of the clinical efficacy, safety and tolerability of the antidepressants vilazodone, levomilnacipran and vortioxetine. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2014;15:2525-42

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Consumer Price Index-All Urban Consumers: U.S. Medical Care, 1982-84. Washington, DC: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2014. http://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/surveymost. Accessed November 26, 2014

- Wu EQ, Greenberg PE, Ben-Hamadi R, et al. Comparing treatment persistence, healthcare resource utilization, and costs in adult patients with major depressive disorder treated with escitalopram or citalopram. Am Heal Drug Benefits 2011;4:78-87

- Wade AG, Toumi I, Hemels MEH. A probabilistic cost-effectiveness analysis of escitalopram, generic citalopram and venlafaxine as a first-line treatment of major depressive disorder in the UK. Curr Med Res Opin 2005;21:631-42

- Wade AG, Toumi I, Hemels MEH. A pharmacoeconomic evaluation of escitalopram versus citalopram in the treatment of severe depression in the United Kingdom. Clin Ther 2005;27:486-96

- Hemels MEH, Kasper S, Walter E, et al. Cost-effectiveness of escitalopram versus citalopram in the treatment of severe depression. Ann Pharmacother 2004;38:954-60

- Sørensen J, Stage KB, Damsbo N, et al. A Danish cost-effectiveness model of escitalopram in comparison with citalopram and venlafaxine as first-line treatments for major depressive disorder in primary care. Nord J Psychiatry 2007;61:100-8

- Demyttenaere K, Hemels MEH, Hudry J, et al. A cost-effectiveness model of escitalopram, citalopram,and venlafaxine as first-line treatment for major depressive disorder in Belgium. Clin Ther 2005;27:111-24

- Lançon C, Verpillat P, Annemans L, et al. Escitalopram in major depressive disorder: clinical benefits and cost effectiveness versus citalopram. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract 2007;11:44-52

- Trkulja V. Is escitalopram really relevantly superior to citalopram in treatment of major depressive disorder? A meta-analysis of head-to-head randomized trials. Croat Med J 2010;51:61-73

- Svensson S, Mansfield PR. Escitalopram: superior to citalopram or a chiral chimera? Psychother Psychosom 2004;73:10-16

- Cantrell CR, Eaddy MT, Shah MB, et al. Methods for evaluating patient adherence to antidepressant therapy: a real-world comparison of adherence and economic outcomes. Med Care 2006;44:300-3

- Sansone RA, Sansone LA. Antidepressant adherence: are patients taking their medications? Innov Clin Neurosci 2012;9:41-6

- Sawada N, Uchida H, Suzuki T, et al. Persistence and compliance to antidepressant treatment in patients with depression: a chart review. BMC Psychiatry 2009;9:38

- Aljumah K, Ahmad Hassali A, AlQhatani S. Examining the relationship between adherence and satisfaction with antidepressant treatment. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2014;10:1433-8

- Hunot VM, Horne R, Leese MN, et al. A cohort study of adherence to antidepressants in primary care: the influence of antidepressant concerns and treatment preferences. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 2007;9:91-9

- Wu E, Greenberg PE, Yang E, et al. Comparison of escitalopram versus citalopram for the treatment of major depressive disorder in a geriatric population. Curr Med Res Opin 2008;24:2587-95

- Wu EQ, Yu AP, Lauzon V, et al. Economic impact of therapeutic substitution of a brand selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor with an alternative generic selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor in patients with major depressive disorder. Ann Pharmacother 2011;45:441-51

- Garnick DW, Hendricks AM, Comstock CB. Measuring quality of care: fundamental information from administrative datasets. Int J Qual Heal Care 1994;6:163-77

- Motheral BR, Fairman KA. The use of claims databases for outcomes research: rationale, challenges, and strategies. Clin Ther 1997;19:346-66

- Melfi CA, Croghan TW. Use of claims data for research on treatment and outcomes of depression care. Med Care 1999;37:AS77-80