Abstract

Objective:

To compare healthcare costs between clopidogrel and prasugrel over 30-day and 365-day periods after discharge from the hospital or emergency room (ER) in patients treated with prasugrel who were hospitalized or had an ER visit for an acute coronary syndrome (ACS) event.

Methods:

This retrospective observational study was based on claims from January 2009–July 2012 in the Truven Health Analytics MarketScan database. Clopidogrel patients were propensity-score matched 1:1 to prasugrel-treated patients. Lin’s frequentist cost history method for censored data and Bayesian zero-inflated gamma regression models were used to analyze healthcare costs.

Results:

The clopidogrel/prasugrel matched-cohort included 10,963 well-matched pairs of patients. Lin’s frequentist analysis showed that outpatient visit costs were significantly lower for clopidogrel than prasugrel after 30 days of follow-up. At 30 days, Bayesian data analysis showed strong evidence that clopidogrel was superior to prasugrel for all-cause and ACS-related hospitalization costs and showed very strong evidence that clopidogrel was superior to prasugrel for all-cause and ACS-related outpatient visit costs. At 365 days, Bayesian data analysis showed strong evidence that clopidogrel was superior to prasugrel for all-cause outpatient visit costs and very strong evidence that clopidogrel was superior to prasugrel for ACS-related outpatient visit costs. Point estimates of the all-cause and ACS-related ER visit costs at 30 days and 365 days were similar, but statistical results were inconclusive because of the large variability in this outcome variable.

Conclusion:

Based on retrospective observational data in a real-world setting, all-cause and ACS-related hospitalization and outpatient visit costs were lower for clopidogrel than prasugrel over 30 days after discharge from a hospitalization or ER visit associated with ACS in patients treated with prasugrel. At 365 days the difference in all-cause and ACS-related outpatient costs remained, but there was little evidence of a difference in either all-cause or ACS-related hospitalization costs.

Introduction

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) encompasses a range of ischemic conditions, including ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), non-STEMI (NSTEMI), and unstable angina (UA). Every year, there are ∼785,000 ACS events in the US, and ∼470,000 patients will experience a recurrent eventCitation1. Advanced treatments and improved control of risk factors have decreased mortality from cardiovascular diseaseCitation2. Despite this, hospital re-admissions for recurrent ACS events are frequent and associated with substantial costsCitation2,Citation3.

ACS has a high economic impact; ACS patients account for costs to the American healthcare system of more than $150 billion annuallyCitation4, with ∼60% of these costs related to ACS hospitalizationCitation3. Among 13,731 patients with ACS followed for a mean of 9.75 months after their initial event, healthcare costs were $22,529 per patient (including the index event) and, of those costs, 71% were attributable to hospitalizationsCitation5. A number of studies have found that both short- and long-term re-admission rates are high among ACS patients and that a relatively important proportion of those re-admissions could be preventableCitation4–12. Considering the sizeable costs of hospital re-admissions to the healthcare system, improved outcomes and treatements for ACS patients are of great interest.

Once patients have been clinically stabilized, standard therapy for ACS includes anti-ischemic and anti-thrombotic drugs. Aspirin decreases the short-term risk of cardiovascular death and non-fatal stroke. Dual anti-platelet therapy with a P2Y12 antagonist and aspirin has been shown to be clinically beneficial and is the standard therapy for ACSCitation13. As a central mediator of the hemostatic response, the P2Y12 receptor, activated by adenosine diphosphate, plays a central role in platelet activation. Of note, P2Y12 antagonist monotherapy is recommended when aspirin is contraindicatedCitation14,Citation15.

The CURE (Clopidogrel in Unstable angina to prevent Recurrent Events) placebo-controlled, double-blind trial showed the combination of clopidogrel and aspirin to be beneficial in ACS patients whether or not they undergo revascularization; based on CURE, clopidogrel was the first P2Y12 antagonist to be approved for use in ACSCitation16. Prasugrel was approved in 2009. In the TRITON-TIMI 38 (Trial to Assess Improvement in Therapeutic Outcomes by Optimizing Platelet Inhibition with Prasugrel-Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 38) trial, prasugrel had greater platelet inhibition and quicker onset of action than clopidogrel, but also was associated with increased bleedingCitation17.

Following an acute coronary event, either clopidogrel or prasugrel is recommended in conjunction with aspirinCitation18. According to most guidelines, clopidogrel and prasugrel should be administered for up to 12 months after an ACS eventCitation19–22. There is a lack of real-world evidence comparing economic outcomes between prasugrel and clopidogrel. This study, thus, aimed to compare healthcare costs between prasugrel and clopidogrel for up to 1 year of treatment in patients receiving prasugrel using healthcare claims from the US.

Methods

Data source

The Truven Health Analytics MarketScan database was used, which combines two separate databases, the Commercial Claims and Encounters database and the Medicare Supplemental and Coordination of Benefits database, to cover all age groups. It includes medical and pharmacy claims from ∼100 health plans, and government and public organizations, representing ∼30 million covered lives. Claims from January 1, 2009–July 31, 2012 were used.

The data elements used in this study included health plan enrolment records, participant demographics, inpatient and outpatient medical services, and outpatient prescription drug dispensing records. The data included in the MarketScan database are de-identified and are in compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 to preserve participant anonymity and confidentiality.

Study design

An observational matched-cohort design was used to compare all-cause and ACS-related costs of hospitalizations, emergency room (ER) visits, and outpatient visits for the 30-day and 1-year periods after initiation of treatment. Patients included in the analysis were ≥18 years of age, with one or more diagnosis claims of ACS (International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision [ICD-9]: 410.xx [except 410.x2], 411.1x, and 411.8x) during a hospitalization or ER visit. The first such event in the study period for which the patient was continuously enrolled (with insurance coverage) for the previous 6 months was the index event (hospitalization or ER visit). Patients also had at least one dispensing for clopidogrel or prasugrel (the date of the first dispensing being defined as the index date) within 14 days of the date of index hospitalization discharge or ER discharge. The 14-day window was used since patients may already have received clopidogrel or prasugrel medication for a short period of time during the hospital stay or ER visit (e.g. medication samples), which would not have been observed in the current study since patients were identified with outpatient pharmacy data because inpatient pharmacy data was not available. The 14-day window thus allowed patients the time to fill their prescription at the pharmacy after their hospital or ER discharge. It is worth noting that patients with an ER admission were discharged the same day. The observation period spanned January 1, 2009–July 31, 2012; patients were followed from the index date to the earliest of the following events: (1) end of treatment compliance (i.e. the first day after which there was a gap of at least 30 days in therapy), (2) end of insurance coverage, (3) end of data availability, or (4) 12 months after the index date. Demographic and baseline characteristics were based on data from the 6-month period before the index ACS event.

Study end-points

The main end-points of the study were actual paid healthcare costs (in $US), including costs of hospitalization, ER visits, and outpatient visits summarized over the 30-day and 365-day periods after the index date. ACS-related costs were determined separately from all-cause costs, based on one or more diagnosis claims of ACS (ICD-9: 410 xx [except 410.x2], 411.1x, and 411.8x). Of note, pharmacy costs were excluded to allow a comparison between clopidogrel and prasugrel cohorts not confounded by pharmacy costs.

Statistical analysis

Patients were matched first by percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) status (yes, no) and then by propensity scores. Propensity score matching was used to adjust for the differences in baseline characteristics and reduce confounding bias. Patient-level propensity scores were calculated using multivariable logistic regression. Within PCI strata, patients in the clopidogrel cohort were matched 1:1 to prasugrel patients based on propensity score calipers of 5% and all baseline characteristics listed in to form the study populations. All analyses with propensity score modeling, matching, and assessment of the quality of matching were part of the design phase of the study before any analyses of outcomes were conducted. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize patient baseline characteristics evaluated during the 6 months before the index ACS event. Means (±standard deviations [SDs]) are reported for continuous variables, and frequencies and percentages are reported for categorical variables. For each baseline variable, balance between treatment groups was assessed using the standardized difference in means; the balance for a particular variable was considered acceptable (good) if the standardized difference was at most 10%. The analysis methods for outcomes were pre-specified before looking at the outcomes data.

Table 1. Demographics and clinical characteristics of clopidogrel/prasugrel pre-matched and matched-cohorts.

Frequentist analysis of healthcare cost

Costs were calculated for each cohort using the method of Lin et al.Citation23 to account for different lengths of observation among studied patients. In our application of this analysis, we assumed that patients were censored at the end of follow-up and had no events that terminated cost accumulation (e.g., no deaths). Cost differences and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) based on 1000 bootstrap replications of the Lin et al.Citation23 analysis were used to compare costs between treatments. A difference in mean costs between treatments was declared statistically significant if the 95% CI did not include 0.

Bayesian data analysis of healthcare cost

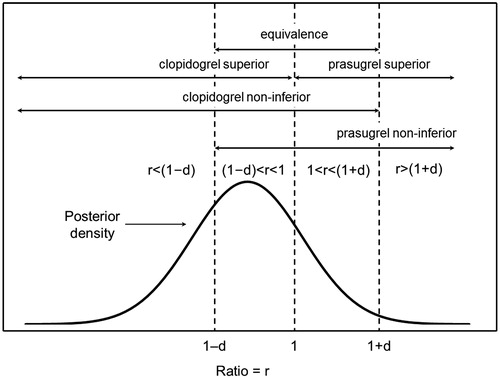

For the Bayesian data analysis, only the subset of cases with complete data up to and including the period of interest were included. A zero-inflated gamma regression model with non-informative flat priors was used and parameters (mean costs) were simulated from the posterior distribution for the model using Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC). From the MCMC samples, means, SDs, medians, and 95% credible intervals of mean healthcare costs are reported for the posterior distribution of mean costs for each cohort. Based on the MCMC for mean costs, the ratio of mean costs (clopidogrel mean/prasugrel mean) was simulated and its posterior distribution was summarized like those for mean costs. The probability that clopidogrel is superior to prasugrel (the posterior probability that the ratio of means is <1), and the probability that prasugrel is superior to clopidogrel (the posterior probability that the ratio of means is >1), were determined, and their ratio, the superiority Bayes factor, is presented. The scheme of Kass and RafteryCitation24 was used to assess the strength of evidence for or against the hypothesis that clopidogrel is superior relative to the hypothesis that prasugrel is superior ().

Table 2. Strength of evidence using Bayes factorsCitation21.

To better understand the magnitude of the differences between treatments, three additional probabilities were calculated at various non-inferiority/equivalence margins (d = 0.05, 0.10, 0.15, 0.20): (1) clopidogrel non-inferior to prasugrel, (2) prasugrel non-inferior to clopidogrel, and (3) clopidogrel equivalent to prasugrel ()Citation25. The minimum equivalence margin or minimum non-inferiority margin at which the probability of equivalence or non-inferiority were at least 0.95, Min(d), was taken to be a measure of the degree of equivalence or non-inferiority; for the data to support a conclusion of equivalence or non-inferiority, the margin would need to be at least Min(d) (minimum margin for which the drugs would be declared equivalent or non-inferior).

Figure 1. Illustration of the five key posterior probabilities. r, ratio of means; d, non-inferiority/equivalence margin. The posterior probabilities are the areas under the posterior density curve for the indicated intervals. This figure has been reproduced with permission from Olson et al.Citation26. © 2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Results

Among the 428,013 patients who had at least one ACS diagnosis, a total of 301,318 had at least 180 days of baseline eligibility prior to their index ACS event. Of those patients, 301,157 were at least 18 years, and 76,355 had at least one dispensing for clopidogrel (n = 65,392) or prasugrel (n = 10,963) between January 2009 and July 2012. In the clopidogrel/prasugrel matched-cohort (n = 10,963/n = 10,963), patients were well matched demographically and by all other baseline characteristics. Among the baseline characteristics that were well matched in the matched-cohort, there were baseline ischemic or bleeding risk factors such as acute myocardial infarction, hypertension, anemia, and previous ischemic stroke/TIA which were unbalanced (i.e., standardized difference in means >10%) in the pre-matcahed cohorts. The mean age of patients in the matched-cohort was 57.4 years in both arms, and 21.5% and 21.9% were female in the clopidogrel and prasugrel arms, respectively ().

Healthcare-associated costs

Frequentist analysis of costs

With the exception of both ACS-related and all-cause outpatient visit costs up to 30 days, there were no statistically significant differences in mean costs between clopidogrel and prasugrel based on Lin’s method (). The differences in mean costs per patient up to 30 days were −$201 in favor of clopidogrel for ACS-related outpatient costs ($1337 and $1538 for clopidogrel and prasugrel, 95% CI = −$337 to −$67) and −$153 in favor of clopidogrel for all-cause outpatient costs ($1740 and $1893 for clopidogrel and prasugrel, 95% CI = −$305 to −$8).

Table 3. Mean ACS-related healthcare cost and all-cause healthcare costs per patient for up to 30 and 365 days of follow-up for clopidogrel/prasugrel matched-cohort.

Although not assessed statistically, some patterns are evident in the cost summaries (). Of the three cost sources, mean costs for ER visits were the lowest and showed relatively small apparent increases from 30 days to 365 days and from ACS-related costs to all-cause costs. At up to 30 days, mean hospitalization costs and outpatient costs were intermediate in magnitude, with mean all-cause outpatient costs somewhat larger than mean ACS-related outpatient costs. Mean hospitalization and outpatient costs at 365 days were generally high; mean all-cause hospitalization costs were 5–10% higher than mean ACS-related hospitalization costs, while mean all-cause outpatient costs were 55–70% higher than mean ACS-related outpatient costs.

Bayesian analysis of costs

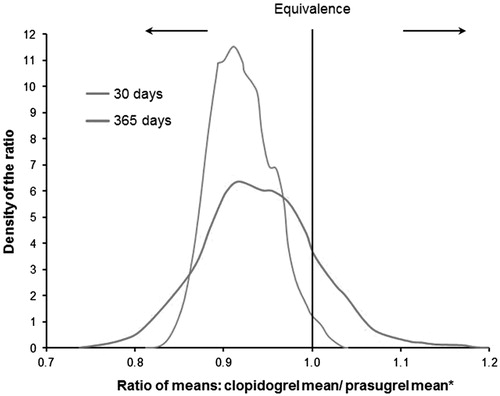

With the exception of the posterior means at 365 days for mean ACS-related hospitalization costs and for mean all-cause hospitalization costs, the posterior means for mean costs across outcome types (hospitalizations, ER visits, and outpatient visits) and causes (ACS-related and all-cause) were similar to those found in the frequentist analysis. The 95% credible intervals for the posterior distribution of the ratio of mean costs did not contain one (i.e., were statistically significant) for 30-day ACS-related hospitalization costs, 30-day and 365-day ACS-related outpatient visit costs, and 30-day all-cause outpatient costs (; ).

Figure 2. Posterior densities for ratio of means of ACS-related hospitalization costs at 30 days and 365 days. *A ratio of <1 indicates that the mean cost of clopidogrel is lower than the mean cost of prasugrel.

Table 4. Bayesian analysis: posterior distribution of ACS-related mean healthcare cost and all-cause mean healthcare costs for matched-cohorts.

and presents posterior probabilities of superiority and superiority Bayes factors for all-cause and ACS-related events at Days 30 and 365. At 30 days, there was strong evidence that clopidogrel was superior to prasugrel for both all-cause and ACS-related hospitalization costs and there was very strong evidence that clopidogrel was superior to prasugrel for all-cause and ACS-related outpatient costs. A similar pattern was seen at Day 365, except that there was no longer evidence of a difference in all-cause hospitalization costs and there was positive (in contrast to strong) evidence that clopidogrel was superior to prasugrel for ACS-related hospitalization costs.

Table 5. Posterior superiority probabilities and superiority Bayes factors for ratio of means of healthcare cost at 30 days (clopidogrel mean/prasugrel mean; clopidogrel, n = 10,562; prasugrel, n = 10,584).

Table 6. Posterior superiority probabilities and superiority Bayes factors for ratio of means of healthcare cost at 365 days (clopidogrel mean/prasugrel mean; clopidogrel, n = 2743; prasugrel, n = 2366).

and present the posterior probabilities of equivalence and non-inferiority for all-cause and ACS-related events across a range of margins for 30 days and 365 days. At 30 days, the minimum margin at which clopidogrel would be declared equivalent to prasugrel (the Min(d)) was between 0.10–0.15 for all cost variables, except ACS-related ER costs and ACS-related outpatient costs, for which the Min(d) was between 0.15–0.20. At 365 days, the equivalence Min(d) was between 0.05–0.10 for all-cause outpatient costs, between 0.10–0.15 for all-cause hospitalization costs, and between 0.15–0.20 for all-cause ER costs, ACS-related hospitalization costs, ACS-related ER costs, and ACS-related outpatient costs. At 30 days, the Min(d) at which prasugrel would be declared non-inferior to clopidogrel was between 0.05–0.10 for all-cause ER costs, between 0.10–0.15 for all-cause hospitalization costs, all-cause outpatient costs, and ACS-related hospitalization costs, and between 0.15–0.20 for ACS-related ER costs and ACS-related outpatient costs. The Min(d) at 30 days at which clopidogrel would be declared non-inferior to prasugrel was between 0.00–0.05 for all-cause hospitalization costs, all-cause outpatient costs, ACS-related hospitalization costs, and ACS-related outpatient costs, and between 0.10–0.15 for all-cause ER costs and ACS-related ER costs. At 365 days, the Min(d) at which prasugrel would be declared non-inferior to clopidogrel was between 0.05–0.10 for all-cause ER costs and all-cause outpatient costs, between 0.10–0.15 for all-cause hospitalization costs and ACS-related ER costs, and between 0.15–0.20 for ACS-related hospitalization costs and ACS-related outpatient costs. The Min(d) at 365 days at which clopidogrel would be declared non-inferior to prasugrel was between 0.00–0.05 for all-cause outpatient costs and ACS-related outpatient costs, between 0.05–0.10 for all-cause hospitalization costs and ACS-related hospitalization costs, and between 0.15–0.20 for all-cause ER costs and ACS-related ER costs.

Table 7. Posterior equivalence and non-inferiority probabilities of healthcare cost at 30 days based on posterior distribution of ratio of means (clopidogrel mean/prasugrel mean; clopidogrel, n = 10,562; prasugrel, n = 10,584).

Table 8. Posterior equivalence and non-inferiority probabilities for ratio of means of healthcare cost at 365 days (clopidogrel mean/prasugrel mean; clopidogrel, n = 2743; prasugrel, n = 2366).

Discussion

Either clopidogrel or prasugrel may be used along with aspirin for long-term anti-thrombotic management of patients with ACS. This analysis of the Truven Health Analytics MarketScan database reports the real-world healthcare costs of patients with ACS using clopidogrel or prasugrel. Bayesian analysis revealed that clopidogrel was superior to prasugrel in hospitalization costs and outpatient costs at 30 days and in outpatient costs at 365 days.

A previous study by the present authors estimated healthcare resource utilization in the same matched-cohorts that were used in the present studyCitation26. In that study there was positive evidence that the mean number of all-cause and ACS-related hospitalizations at 1 month were smaller for clopidogrel than for prasugrel, which is consistent with the cost findings at 30 days for these events of the present study. In the previous study, there was little evidence of a difference in these means (for mean number of all-cause and ACS-related hospitalizations) at 12 months, which is consistent with the reduced evidence for a difference in cost for these events over 365 days in this study. The cost findings of this study for ACS-related outpatient visits at 365 days are consistent with the number of such events at 12 months in the previous study. The finding of positive evidence for a difference in cost for all-cause outpatient visits at 30 days in this study is inconsistent with the finding of little evidence for a difference in the mean numbers of these events in the previous study. Finally, in both studies there was little evidence of differences between clopidogrel and prasugrel for the ER visit outcomes.

As noted below, a limitation of this study is that a Bayesian analysis that accounted for censoring of the cost data could not be implemented. This would not appreciably affect the 30-day cost results, but could affect the 365-day results. If the data that were missing because of censoring were missing completely at random, then an analysis based on the completers, as it was done in the Bayesian analyses, would be valid. An analysis not reported here supports the assumption that the missing data were missing completely at random for all outcomes except the ACS-related and all-cause hospitalization costs at 365 days. Because our findings for these outcomes are inconclusive, whether or not there is a difference remains an open question. So, the conclusions of the study were not affected by this limitation.

Well-designed observational studies with appropriate statistical techniques that adjust for potential confounding factors through matching techniques provide valuable information, with real-life scenarios and high generalizability. Since no equivalence/non-inferiority margins were pre-specified, we have assessed all of the hypotheses across a range of equivalence/non-inferiority margins.

Costs for clopidogrel have high probabilities to be superior (re-hospitalization, outpatient) or non-inferior/equivalent (ER) with the Bayesian approach, given reasonable choices of margins. A cost-effectiveness study was based on data from the TRITON-TIMI 38 analyzed resource use data for 6705 ACS patients with planned PCI over almost 15 monthsCitation27. Based on event rates in the trial and diagnosis-related group (DRG)-related cost methodology, it was estimated that endpoint-related re-hospitalization costs were $218 more for clopidogrel than prasugrel in the initial 30 days of treatment and $530 more for clopidogrel than prasugrel over the median duration of follow-up of 14.7 months in both groups, with neither difference being statistically significant. Two studies that developed economic models based on event rates from TRITON-TIMI 38 found unfavorable re-hospitalization cost-effectiveness ratios for clopidogrel relative to prasugrelCitation28,Citation29. The results of these economic modeling studies, which assign costs based on event rates in the TRITON-TIMI 38 trial and other non-primary sources, and those of our study, which are based on primary cost data, suggest that further real-world studies based on primary cost data are warranted.

Our study is subject to a number of limitations. First, claims data, while extremely valuable in establishing treatment patterns and healthcare resource utilization, are not collected for research purposes and may contain billing inaccuracies or missing data for procedures, diagnoses, and costs. Second, retrospective, observational designs are inherently susceptible to various biases, such as classification bias and hidden confoundersCitation30. False-positive or false-negative identification of an ACS event may be a factor. The effects of unmeasured variables are not known, and the results of this study may not be generalizable to other patient populations. Finally, for the frequentist analysis, Lin et al.’sCitation23 estimate was applied to adjust for censored count data. However, there is no censoring adjustment method available in the Bayesian analysis setting. Therefore, only complete patient data up to the analysis time point were used, although this should have only a minor impact, if any, on the 30-day results.

Conclusion

Based on retrospective observational data generated in a real-world setting, all-cause and ACS-related hospitalization costs and outpatient visit costs were lower for clopidogrel than for prasugrel over the 30 days after discharge from a hospitalization or ER visit associated with ACS in patients treated with prasugrel. At 365 days the difference in all-cause and ACS-related outpatient costs remained, but there was little evidence of a difference in either all-cause or ACS-related hospitalization costs. There was little evidence of a difference in all-cause and ACS-related ER visit costs at 30 and 365 days.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This research was funded by Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, Raritan, NJ.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

PL, FL, KD, and GG are employees of Groupe d’analyse, Ltée, a consulting company that has received research grants from Janssen Scientific Affairs. WHO, YM, CC, and JS are employees of Janssen Scientific Affairs. SML has received research grants from Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Lisa Grauer, MSc, who provided editorial support, with funding from Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC.

References

- Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2011 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2011;123:e18-e209

- Bassand J-P, Hamm CW, Ardissino D, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J 2007;28:1598-660

- Menzin J, Wygant G, Hauch O, et al. One-year costs of ischemic heart disease among patients with acute coronary syndromes: findings from a multi-employer claims database. Curr Med Res Opin 2008;24:461-8

- Kolansky DM. Acute coronary syndromes: morbidity, mortality, and pharmacoeconomic burden. Am J Managed Care 2009;15(2 Suppl):S36-41

- Etemad LR, McCollam PL. Total first-year costs of acute coronary syndrome in a managed care setting. J Managed Care Pharm: JMCP 2005;11:300-6

- McCollam P, Etemad L. Cost of care for new-onset acute coronary syndrome patients who undergo coronary revascularization. J Invasive Cardiol 2005;17:307-11

- Gurfinkel EP, Perez de la Hoz R, Brito VM, et al. Invasive vs non-invasive treatment in acute coronary syndromes and prior bypass surgery. Int J Cardiol 2007;119:65-72

- Yang Z, Olomu A, Corser W, et al. Outpatient medication use and health outcomes in post-acute coronary syndrome patients. Am J Managed Care 2006;12:581-7

- Jennings DL, Petricca JC, Yageman LA, et al. Predictors of rehospitalization after acute coronary syndromes. Am J Health-Syst Pharm: AJHP: Off J Am Soc Health-Syst Pharm 2006;63:367-72

- Krumholz HM, Lin Z, Keenan PS, et al. Relationship between hospital readmission and mortality rates for patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, or pneumonia. JAMA 2013;309:587-93

- Kociol RD, Lopes RD, Clare R, et al. International variation in and factors associated with hospital readmission after myocardial infarction. JAMA 2012;307:66-74

- Hess CN, Shah BR, Peng SA, et al. Association of early physician follow-up and 30-day readmission after non-ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction among older patients. Circulation 2013;128:1206-13

- Gurbel PA, Tantry US. Combination antithrombotic therapies. Circulation 2010;121:569-83

- Anderson JL, Adams CD, Antman EM, et al. ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina/non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction–executive summary. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;50:e1-157

- Jneid H, Anderson JL, Wright RS, et al. 2012 ACCF/AHA focused update of the guideline for the management of patients with unstable angina/non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (updating the 2007 guideline and replacing the 2011 focused update). Circulation 2012;126:875-910

- Fox KAA, Mehta SR, Peters R, et al. Benefits and risks of the combination of clopidogrel and aspirin in patients undergoing surgical revascularization for non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome: the Clopidogrel in Unstable angina to prevent Recurrent ischemic Events (CURE) trial. Circulation 2004;110:1202-8

- Wiviott SD, Trenk D, Frelinger AL, et al. Prasugrel compared with high loading- and maintenance-dose clopidogrel in patients with planned percutaneous coronary intervention: the prasugrel in comparison to clopidogrel for inhibition of platelet activation and aggregation-thrombolysis in myocardial infarction 44 trial. Circulation 2007;116:2923-32

- Levine GN, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI guideline for percutaneous coronary intervention. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2012;79:453-495

- Heart K, Nauheim B, Bassand J, et al. Updated ESC guidelines for managing patients with suspected non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J 2011;32:2909-10

- Steg PG, James SK, Atar D, et al. ESC guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J 2012;33:2569-619

- Amsterdam EA, Wenger NK, Brindi RG, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2014;130:e344-426

- O’Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2013;127:529-55

- Lin DY, Feuer EJ, Etzioni R, et al. Estimating medical costs from incomplete follow-up data. Biometrics 1997;53:419-34

- Kass RE, Raftery AE. Bayes factors. J Am Stat Ass 1995;90:773-95

- Kruschke JK. Bayesian assessment of null values via parameter estimation and model comparison. Persp Psychol 2011;6:299-312

- Olson WH, Ma Y-W, Laliberté F, et al. Prasugrel vs. clopidogrel in acute coronary syndrome patients treated with prasugrel. J Clin Pharm Ther 2014;39:663-72

- Mahoney EM, Wang K, Arnold SV, et al. Cost-effectiveness of prasugrel versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes and planned percutaneous coronary intervention: results from the trial to assess improvement in therapeutic outcomes by optimizing platelet inhibition with Prasug. Circulation 2010;121:71-9

- Davies A, Bakhai A, Schmitt C, et al. Prasugrel vs clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndrome undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: a model-based cost-effectiveness analysis for Germany, Sweden, the Netherlands, and Turkey. J Med Econ 2013;16:510-21

- Mauskopf JA, Graham JB, Bae JP, et al. Cost-effectiveness of prasugrel in a US managed care population. J Med Econ 2012;15:166-74

- Benson K, Hartz AJ. A comparison of observational studies and randomized, controlled trials. N Engl J Med 2000;342:1878-86