Abstract

Objective:

To estimate, from a US payer perspective, the cost offsets of treating gram positive acute bacterial skin and skin-structure infections (ABSSSI) with varied hospital length of stay (LOS) followed by outpatient care, as well as the cost implications of avoiding hospital admission.

Methods:

Economic drivers of care were estimated using a literature-based economic model incorporating inpatient and outpatient components. The model incorporated equal efficacy, adverse events (AE), resource use, and costs from literature. Costs of once- and twice-daily outpatient infusions to achieve a 14-day treatment were analyzed. Sensitivity analyses were performed. Costs were adjusted to 2015 US$.

Results:

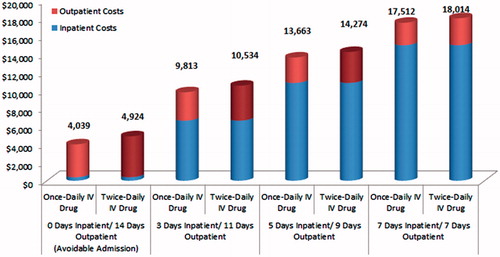

Total non-drug medical cost for treatment of ABSSSI entirely in the outpatient setting to avoid hospital admission was the lowest among all scenarios and ranged from $4039–$4924. Total non-drug cost for ABSSSI treated in the inpatient setting ranged from $9813 (3 days LOS) to $18,014 (7 days LOS). Inpatient vs outpatient cost breakdown was: 3 days inpatient ($6657)/11 days outpatient ($3156–$3877); 7 days inpatient ($15,017)/7 days outpatient ($2495–$2997). Sensitivity analyses revealed a key outpatient cost driver to be peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) costs (average per patient cost of $873 for placement and $205 for complications).

Limitations:

Drug and indirect costs were excluded and resource use was not differentiated by ABSSSI type. It was assumed that successful ABSSSI treatment takes up to 14 days per the product labels, and that once-daily and twice-daily antibiotics have equal efficacy.

Conclusion:

Shifting ABSSSI care to outpatient settings may result in medical cost savings greater than 53%. Typical outpatient scenarios represent 14–37% of total medical cost, with PICC accounting for 28–43% of the outpatient burden. The value of new ABSSSI therapies will be driven by eliminating the need for PICC line, reducing length of stay and the ability to completely avoid a hospital stay.

Introduction

ABSSSI are acute bacterial skin and soft tissue infections most often presenting as cellulitis and abscessesCitation1, with other clinical presentations including tissue necrosis, wound infections, burns, and sepsis. Staphylococcus aureus and recently methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) have been shown to be a common cause of ABSSSI. The emergence of MRSA in almost 60% of ABSSSI cases has made it difficult to successfully treat patients with many established antibioticsCitation2. Hospitalizations due to ABSSSI diagnoses such as cellulitis may be considered avoidable, since they can be managed in ambulatory settingsCitation3,Citation4. Nevertheless, ABSSSI represents a significant clinical and cost burden to both the US healthcare system and society at large. Steady increase in the incidence of community acquired ABSSSI has resulted in growing emergency department (ED) visits and inpatient stays for ABSSSI diagnoses. Total hospital admissions for ABSSSI increased by 29% between 2000–2004, whereas the diagnoses for ABSSSI in ED visits increased by nearly 3-times to 3.4 million ED visits from 1993–2005Citation5,Citation6. In 2010, nearly three quarters of inpatient admissions with a principal diagnosis of ABSSS, originated from the EDCitation7. The rise in hospitalizations of patients with MRSA ABSSSI may lead to an increase in the incidence of hospital acquired infections (HAIs) and re-admissions. Under the Affordable Care Act, hospitals will be penalized for higher than average rates of re-admissions, with the penalty increasing each yearCitation8. Avoiding hospital admission of ABSSSI patients and treating them in outpatient settings can be a valuable alternative aimed at reducing costs and improving the quality of care.

The objective of the present study was to estimate the potential cost savings associated with avoiding hospital admission by shifting treatment of gram positive ABSSSI from inpatient to outpatient settings, including an assessment of the cost burden of administering intravenous antibiotics through peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) lines.

Patients and methods

A literature-based economic model was developed to estimate the non-drug medical costs of comprehensive treatment of gram positive ABSSSI in inpatient and outpatient settings. Treatment of ABSSSI with two representative classes of antibiotics was compared to understand the typical drivers of treatment cost. Drug costs were excluded from the analysis, since the focus was to understand cost drivers in the inpatient and outpatient setting. The model compared resource use costs for ABSSSI treatment assuming either a typical glycopeptide antibiotic with a twice daily IV dose or a typical once daily IV antibiotic. ABSSSI cases with or without MRSA were considered in the analysis. No distinction was made between resource use and success rates of antibiotic treatment against different types of ABSSSI infections, such as cellulitis, abscess, wound, ulcer, etc. The clinical studies reported only aggregated data on all types of ABSSSI infections.

Analysis perspective

The analysis was carried out from a US payer perspective. Hence, only direct medical costs borne by a third-party payer are included, and indirect costs such as loss of productivity, which are not typically borne by payers, are excluded. All costs are expressed in 2015 US$.

Analysis time frame

This was a short-term economic model due to the acute nature of the bacterial infections being studied. Successful treatment of ABSSSI was assumed to take up to 14 days of antibiotic therapy based on current product labeling and expert opinion.

Model structure

Economic model structure was based on a simple decision tree () which mimicked the commonly used treatment pathway for ABSSSI patients. Patients entered the model with a suspected gram positive ABSSSI with or without MRSA. Patients were treated with a typical glycopeptide antibiotic with a twice daily IV administration or a typical once daily IV antibiotic. With the exception of the avoidable admission scenario, all patients started antibiotic treatment in the inpatient setting and were later shifted to the outpatient setting with varying length of stay. Under the avoidable admissions scenario, patients were treated entirely in the outpatient setting. Upon discharge from the hospital, patients on once daily IV antibiotic received infusions in the physician office, whereas patients taking a typical twice daily glycopeptide antibiotic received infusions at home via home care service. All patients were administered IV infusions using a PICC line. All patients required a follow-up physician visit after being discharged from the hospital. In the case of treatment success, patients received 14 days of treatment before exiting the model.

Model inputs

Inputs for the economic model consisted of clinical assumptions and resource use patterns that were gathered from published literature and validated using multiple rounds of expert review.

Clinical inputs

Equal efficacy was assumed for both once and twice daily IV antibiotics as differences in the efficacy of treatments would result in different incidence rates and costs of AEs. The model assumed a clinical success rate of ∼90% for ABSSSI based on various clinical studies and comparatorsCitation9,Citation10. For the remaining ∼10% considered failures, the model assumed that AEs requiring a switch of treatment (∼3%) require an additional 5-day LOS based on published dataCitation11. AE rates were assumed to be similar, regardless of frequency of administration, given the approach to analysis taken by Edelsburg et al.Citation11, which included a variety of antibiotics with various dosing frequencies. Patients assigned to a typical glycopeptide required laboratory testing to test renal function panel and check drug trough levels.

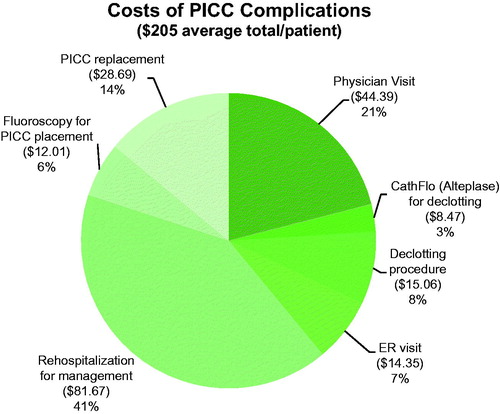

Administration of IV antibiotics through PICC lines may pose a risk of complications such as thrombosis, phlebitis, or catheter occlusion due to clotting of PICC, catheter-related infections, etc.Citation12. Serious cases of phlebitis may require replacement of the PICC line and a physician visit, whereas clotting and subsequent occlusion of catheters may require a declotting procedure or use of a tissue plasminogen activator such as alteplase. Catheter-related infections may require a physician visit or ER visit for administration of a new antibiotic. Based on an analysis carried out by Tice et al.Citation13, it was assumed that 17% of patients using PICC in the outpatient setting would require a physician visit, 7% would use a declotting procedure, and another 7% would use alteplase for management of PICC complications. Additionally, it was assumed, based on an analysis of PICC complications in the outpatient setting by Moureau et al.Citation12, that 2% of patients using PICC in the outpatient setting would require an ER visit, 1% would require re-hospitalization, and 5% would require PICC replacement and fluoroscopy for PICC replacement.

Cost inputs

presents the detailed cost inputs and references for the inpatient and outpatient components of ABSSSI treatment. Inpatient costs included the cost for hospital LOS and the cost of AEs (5 days of hospital LOS penalty). Outpatient costs included PICC line costs for administration of IV antibiotic, cost of IV infusion received at home via home care service or at a physician office, cost of follow-up physician visits, and laboratory costs for patients treated with a typical glycopeptide. All costs were obtained from a targeted review of the literature, as well as reimbursement rates for the specific current procedural terminology (CPT) codes. Inpatient resource use inputs included cost of hospital length of stay for treatment of ABSSSI ($2090/day) and the cost associated with the additional LOS due to treatment of AEs (5* $2090/day). Outpatient resource use inputs included the cost of IV infusion received at home via daily home care ($220) or at physician office ($165), cost of follow-up physician visits ($261), cost of laboratory testing for typical glycopeptide ($118), cost of PICC placement ($633), fluoroscopy for PICC placement ($240), and cost of PICC complications ($205). Cost of PICC complications was calculated based on the resource use pattern explained previously. Per patient per year cost of PICC complications was calculated by multiplying resource use costs by the percentages of patients requiring the specific resource use (). The resource use for treating PICC complications included an additional physician visit ($261), visit to an emergency room ($717), cost of Alteplase ($121), cost of de-clotting procedure ($215), cost of PICC replacement ($574), cost of fluoroscopy for replacement of PICC ($240), and cost of re-hospitalization for management of complications ($8167). All costs reflected 2015 costing resources or were inflated to 2015 US dollars.

Table 1. Medical resource use cost inputs.

Table 2. Cost calculations of PICC complications.

Model analyses

Several LOS scenarios were analyzed to assess the total non-drug medical cost of ABSSSI treatment and the cost implications of shifting patients to the outpatient setting. Inpatient length of stay scenarios included 0, 3, 5, and 7 days followed by outpatient treatment for 14, 11, 9, and 7 days, respectively. Scenarios were based on published data indicating an average LOS for ABSSSI patients was typically 4–6 days in the USCitation14. An avoidable admission scenario (0 days LOS, 14 days outpatient treatment) was analyzed to understand costs of treating ABSSSI completely in the outpatient setting. This scenario was based on the findings of a recent study showing that 41.5% of hospital admissions for skin and soft tissue infection were solely for the administration of IV antibioticsCitation15. In this avoidable admission scenario, patients were never hospitalized, except for treatment of AEs which incurred a 5-day LOS penalty, similar to all other scenarios. The model output generated the average total cost for treatment of ABSSSI per patient per year, as well as the average annual cost of the inpatient and outpatient components of ABSSSI treatment.

Univariate sensitivity analyses were carried out to understand the impact of clinical and cost inputs on both the total costs of ABSSSI treatment (inpatient and outpatient) and only on the outpatient costs. For both sensitivity analyses, the model inputs were varied by ±30%, one at a time, in order to assess their impact on the cost of care. For the sensitivity analysis on total cost of ABSSSI treatment, hospital LOS was assumed to be 5 days and 7 days for once daily and twice daily IV drugs, respectively. For the sensitivity analysis on outpatient costs of ABSSSI treatment, the inpatient LOS was set to zero, and it was assumed that patients were treated entirely in the outpatient setting.

Results

Total costs of ABSSSI treatment were the lowest for the avoidable admission scenario. The total non-drug medical cost was $4039 and $4924 for once daily IV drug and twice daily IV drug, respectively. During the 14 days of outpatient treatment of ABSSSI, the cost components of therapy included IV infusion at the physician office ($2313) or twice daily IV infusion at home ($3081), and the cost of AEs ($387) regardless of treatment type.

For model scenarios assuming patients incur a hospital stay, the total non-drug cost of ABSSSI treatment ranged from $9813–$18,014 (as shown in ), depending on the length of stay and the choice of antibiotic (once daily vs twice daily). The detailed costs for various LOS scenarios and the cost savings associated with 0 days, 3 days, and 5 days LOS scenarios compared to the 7 days LOS scenario are presented in and , respectively. As length of inpatient stay increased, costs increased. The 7 days inpatient/7 days outpatient scenario was associated with the highest per patient per year cost ($17,512 for once daily IV and $18,014 for twice daily IV treatments), whereas 3 days inpatient/11 days outpatient scenario was associated with the lowest per patient per year cost ($9813 for once daily IV drug and $10,534 for twice daily IV drug). The avoidable admission scenario led to savings of $5610–$5774 (53–59%), $9350–$9624 (66–70%), and $13,090–$13,473 (73–77%) compared to 3 days, 5 days, and 7 days LOS scenarios, respectively. Hospital LOS cost ($2090/day) was the largest component of total cost, increasing from $6270 for the 3 days inpatient scenario to $14,630 for the 7 days inpatient scenario. Cost of AEs remained constant at $387 for all model scenarios.

Table 3. Detailed cost outcomes for model scenarios.

Table 4. Cost savings associated with shifting ABSSSI care to the outpatient setting.

The outpatient component of costs ranged from $2495–$3877, depending on the number of days of outpatient treatment and the type of drug. For the once daily IV treatment, outpatient costs ranged from $2495 (7 days inpatient/7 days outpatient scenario) to $3156 (3 days inpatient/11 days outpatient scenario), whereas, for the twice daily IV treatment, outpatient costs ranged from $2997 (7 days inpatient/7 days outpatient scenario) to $3877 (3 days inpatient/11 days outpatient scenario). Outpatient component of care ranged from 14–37% of total cost of treatment as outpatient days increased. PICC cost, at $1078, represented the largest component of outpatient costs, ranging from 28–43% of outpatient costs. PICC complications were estimated to cost on average $205 per patient. The detailed costs of PICC complications including the individual resource use costs and incidence rates are illustrated in .

Sensitivity analysis results

Univariate sensitivity analyses were carried out to identify model inputs having maximum impact on the total cost and outpatient cost outcomes.

Univariate sensitivity analysis on total cost of ABSSSI treatment and outpatient cost

Based on the sensitivity analysis on the total cost of ABSSSI treatment, LOS was the top driver of total cost for both once and twice daily IV drugs followed by length of treatment (). Varying the cost per inpatient day by ±30% changed the total cost of care by ±$3135 and ±$4389 for once and twice daily IV drugs, respectively.

Table 5. Top drivers of total cost of ABSSSI treatment.

When performing the sensitivity analysis on the outpatient cost component of ABSSSI treatment, the top driver was the cost of the outpatient infusion visit for both once and twice daily IV drugs followed by PICC and physician visit costs (). Varying the IV infusion visit cost by ±30% changed the outpatient costs of care by ±$694 and ±$924 for once and twice daily IV drugs, respectively.

Table 6. Top drivers of outpatient cost of ABSSSI treatment.

Sensitivity analysis on PICC costs

PICC costs were the largest component of the outpatient costs. A series of univariate sensitivity analyses were carried out on the PICC complication costs to better understand their impact on total PICC costs and overall costs. The model assumes that each patient developing a PICC complication will incur the cost of a GP visit. Chapman et al.Citation16 reported that, on average, 25% of patients receiving OPAT will experience an adverse reaction. Seckold et al.Citation17 reported that, on average, 22.3% of non-oncology patients using PICC suffered from complications, while the complication rate ranged from 8–50% in all patients. Based on this data, the percentage of patients requiring a GP visit was varied from 8–50%. This resulted in the cost of PICC complications ranging from $108–$549 compared to $205 in the base case, while the total PICC costs ranged from $981–$1422 compared to $1078 in the base case. When the percentage of patients needing a declotting procedure was changed to 10.3%, based on the study by Seckold et al.Citation17, the average PICC complication costs increased marginally to $209, while the total PICC costs went up to $1082. Varying the percentage of patients requiring re-hospitalization for management of PICC complications from 4% to 12% based on numbers reported by Chapman et al.Citation16 (compared to 6% at baseline), resulted in average PICC complications cost ranging from $175–$286, while the total PICC costs ranged from $1048–$1159. Changing the percentage of patients requiring catheter replacement from 29% in the base case to 35% according to Leroyer et al.Citation18 increased the PICC complications costs to $208, and the total PICC costs increased to $1081.

Overall, these univariate sensitivity analyses resulted in PICC complication costs ranging from $181–$388, while the total PICC costs ranged from $1054–$1261.

Discussion

Avoidable admissions

Inpatient bed day cost and hospital LOS were the top two drivers impacting the total direct medical costs of treating ABSSSI, thus shifting care to outpatient settings may present a significant opportunity to offset hospital costs. In our analysis, potential cost savings under the avoidable admission scenario ranged from $13,090–$13,473, depending upon the frequency of infusion used (once daily or twice daily IV), compared to the 7 days inpatient and 7 days outpatient treatment scenario.

With the passage of the healthcare reform, the focus of national healthcare policy has been to improve the quality of care and simultaneously reduce costs. Unnecessary and duplicative services such as re-admissions and HAIs offer potential areas for improving quality and reducing costs. More than one-fifth of Medicare beneficiaries who are discharged from hospitals are re-admitted within 30 days, costing Medicare $17.4 billion in 2004 aloneCitation19. Therefore, Medicare and some other payers have resorted to financial penalties for hospitals performing poorly on quality indicators for re-admissions and HAIs. Under the Affordable Care Act of 2010, hospitals will be penalized for preventable re-admissions and will not be reimbursed for HAIs if they were not present on admissionCitation20. Avoiding admission of clinically stable MRSA infected patients could potentially reduce incidence of HAIs and re-admissions associated with treatment of HAI. This could translate into even higher cost savings for the avoidable admissions scenario. Others also have argued that allowing patients to self-administer antibiotics in the outpatient setting instead of keeping them hospitalized until they finish the entire course of treatment can be both clinically and financially advantageousCitation21.

Shifts to outpatient care

In a recent prospective study of 12 US emergency departments (n = 619 patients), Talan et al.Citation15 found that 41.5% of hospital admissions for skin and soft tissue infection were solely for the administration of IV antibiotics. If a patient can be treated efficiently and effectively in the outpatient setting, at home or in the physician office, the reimbursement mechanisms can be designed to incentivize the transition to shifting patients and avoiding admissions. Payers can work to adopt a reimbursement policy that facilitates treatment in the outpatient settings whenever clinically appropriate. Although private payers have started reimbursement of outpatient antibiotic therapy provided at home or in the physician office, Medicare does not currently cover antibiotic treatment provided at home, unless the patient is homeboundCitation22. The policy may be based on the thinking that favorable reimbursement policies for coverage of antibiotic treatment received at home would result in an increase in costs for Medicare. A report published by the Office of Technology Assessment concluded that, despite potential reduction in hospital payments, coverage of home infusion would lead to overall cost increasesCitation23. The data from this current analysis would support the need for an updated feasibility assessment of coverage of antibiotic treatment provided at home.

Clinical and economic burden of PICC

Although shifting ABSSSI care to outpatient settings may reduce overall costs associated with hospitalization, costs associated with PICC use and associated PICC complications in the outpatient setting remain a clinical and economic burden, accounting for 28–43% of outpatient antibiotic delivery costs. In our analysis, insertion of the PICC line and the management of complications were significant drivers of outpatient costs for administration of IV antibiotics in ABSSSI treatment. From a clinical perspective, therapies not requiring PICC insertion would be beneficial. A very recent study of 2193 PICCs in 1652 patients confirmed that certain types of PICC lines were associated with increased risk of bloodstream infection and venous thrombus (VT) formationCitation24.

Intravenous antibiotics with efficient extended dosing regimens (once weekly or longer intervals) that do not require administration through PICC lines have been recently approved. These new IV antibiotics may alter the treatment landscape by providing new treatment options to shift care into the outpatient setting, while at the same time reducing costs by avoiding hospital admissions in eligible patients, reducing the need for PICC line and the associated risks and costs of complications, and by significantly reducing the number of infusion visits in the outpatient setting. In this new outpatient-centered environment, IV antibiotics requiring the use of PICC for daily administration may be viewed less favorably with regard to patient preference and payer reimbursement.

Limitations

Our study estimated the economic burden associated with ABSSSI using an economic modeling approach, hence the study has limitations that are consistent with most economic modeling exercises that attempt to model a typical practice or scenario. Nevertheless, our assumptions were almost all literature based, and sensitivity analyses indicated that results were consistent and expected. While models can never replace real-world studies, they serve as one important method to provide comparative data in a consistent framework using typical assumptions about a patient population.

In addition, a limitation of this analysis was that it focused on IV treatments for more serious ABSSSI infections that would typically require initiation of treatment in a hospital setting. As such, our analysis did not address oral antimicrobial medications which may also prevent hospitalization and avoid PICC lines in some instances. Furthermore, there may be other reasons why patients are admitted to the hospital besides the need for IV therapy, such as social reasons or management of co-morbid conditions. In stable patients without a need for extended hospitalization, the value of this analysis underscored the importance of therapeutic strategies that help to reduce hospital stay as well as reduce IV outpatient antibiotic treatment and PICC line use.

Conclusion

The present analysis sheds light on the main cost drivers of ABSSSI parenteral treatment and potential cost savings associated with avoiding hospital admission by shifting care to outpatient settings. When considering solely outpatient parenteral treatment of ABSSSI, costs are mainly driven by outpatient infusion visits in the physician’s office or via homecare infusions, as well as the cost burden of PICC lines and associated complications. In an avoidable admission scenario, completely shifting ABSSSI treatment to outpatient settings resulted in medical cost offsets greater than 53%. Treatment scenarios with both inpatient and outpatient components revealed that reduction in LOS results in lower total direct medical costs for ABSSSI patients, with the outpatient component accounting for roughly one third of the cost of treatment.

In conclusion, the economic burden of hospital LOS and the use of PICC lines in outpatient parenteral antibiotic delivery for the treatment of ABSSSI is substantial. Treatment strategies that avoid the use of PICC and reduce hospital LOS or avoid it completely would be beneficial from the hospital and societal perspective.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was sponsored by Durata Therapeutics, in Chicago, IL.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

MD and KJn were employees of Durata Therapeutics (“Durata”). VE, AK, MX and JS were employees of Pharmerit International and were paid consultants to Durata in the development and execution of this study. JME peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgments

No assistance in the preparation of this article is to be declared.

References

- Ray GT, Suaya JA, Baxter R. Incidence, microbiology, and patient characteristics of skin and soft-tissue infections in a U.S. population: a retrospective population-based study. BMC Infect Dis 2013;13:252

- Moran GJ, Krishnadasan A, Gorwitz RJ, et al. Methicillin-resistant S. aureus infections among patients in the emergency department. N Engl J Med 2006;355:666-74

- Carter MW. Factors associated with ambulatory care–sensitive hospitalizations among nursing home residents. J Aging Health 2003;15:295-331

- Grabowski DC, O’Malley AJ, Barhydt NR. The costs and potential savings associated with nursing home hospitalizations. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007;26:1753-61

- Edelsberg J, Berger A, Weber DJ, et al. Clinical and economic consequences of failure of initial antibiotic therapy for hospitalized patients with complicated skin and skin-structure infections. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2008;29:160-9

- Pallin DJ, Egan DJ, Pelletier AJ, et al. Increased US Emergency Department visits for skin and soft tissue infections, and changes in antibiotic choices, during the emergence of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Ann Emerg Med 2008;51:291-29

- Lapensee K, Fan W, Economic burden of hospitalization with antibiotic treatment for ABSSSI in the US: an analysis of the Premier Hospital Database. Poster presented at the International Society of Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research, 17th Annual International Meeting, Washington DC, June 2012. Poster code: PIN22

- Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. CMS finalizes hospital readmissions reduction program in IPPS final rule. 2011. Available online at: http://cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/Readmissions-Reduction-Program.html/. Accessed August 27, 2015

- Boucher HW, Wilcox M, Talbot GH, et al. Once-weekly dalbavancin versus daily conventional therapy for skin infection. N Engl J Med 2014;370:2169-79

- Martone WJ, Lindfield KC, Katz DE. Outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy with daptomycin: insights from a patient registry. Int J Clin Pract 2008;62:1183-7

- Edelsberg J, Taneja C, Zervos M, et al. Trends in US hospital admissions for skin and soft tissue infections. Emerging Infect Dis 2009;15:1516-18

- Moureau N, Poole S, Murdock MA, et al. Central venous catheters in home infusion care: outcomes analysis in 50,470 patients. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2002;13:1009-16

- Tice A, Marsh PK, Craven PC, et al. Peripherally inserted central venous catheters for OP intravenous antibiotic therapy. Infect Dis Clin Pract 1993;2:186-90

- Barrett M, Whalen D. HCUP Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) Comparison Report. In: HCUP Methods Series Report, 2010-03. Rockville, MD: US Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2007.

- Talan DA, Salhi B, Moran GJ, et al. Factors associated with the decision to hospitalize emergency department patients with a skin and soft tissue infection. W J Emerg Med 2014;16:89-97

- Chapman AL, Seaton RA, Cooper MA, et al. Good practice recommendations for outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy (OPAT) in adults in the UK: a consensus statement. J Antimicrobial Chemo 2012;67:1053-62

- Seckold TL, Walker S, Dwyer T. A comparison of silicone and polyurethane PICC lines and postinsertion complication rates: a systematic review. J Vasc Access 2015;16:167-77

- Leroyer C, Lasheras A, Marie V, et al. Prospective follow-up of complications related to peripherally inserted central catheters. Méd Malad Infect 2013;43:350-5

- Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med 2009;360:1418-8

- Kavanagh KT. Financial incentives to promote health care quality: the hospital acquired conditions nonpayment policy. Social Work Public Health 2011;26:524-41

- Farroni JS, Zwelling L, Cortes J, et al. Saving Medicare through patient-centered changes—the case of injectables. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1572-3

- Paladino JA, Poretz D. OP parenteral antimicrobial therapy today. Clin Infect Dis: Offic Pub Infect Dis Soc Am 2010;51(Suppl 2):S198-208

- Office of Technology Assessment. Home drug infusion therapy under Medicare, OTA-H-509. Washington, DC: Office of Technology Assessment; 1992

- Baxi SM, Shuman EK, Scipione CA, et al. Impact of postplacement adjustment of peripherally inserted central catheters on the risk of bloodstream infection and venous thrombus formation. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2013;34:785-92

- Ingenix. National fee analyzer. Eden Prairie, MN: Ingenix; 2015

- Tice AD, Turpin RS, Hoey CT, et al. Comparative costs of ertapenem and piperacillin-tazobactam in the treatment of diabetic foot infections. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2007;64:1080-6

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. Consumer Price Index; Medical Component. Washington, DC: Bureau of Labor Statistics; 2015

- Tice AD, Hoaglund PA, Nolet B, et al. Cost perspectives for OP intravenous antimicrobial therapy. Pharmacotherapy 2002;22(2 Pt 2):63S-70S

- Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, Hospital adjusted expenses per inpatient day. 2012. Available online at: http://kff.org/other/state-indicator/expenses-per-inpatient-day. Accessed August 27, 2015