Abstract

Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) is a prevalent illness that is frequently associated with significant disability, morbidity and mortality. Despite the development and availability of numerous treatment options for MDD, studies have shown that antidepressant monotherapy yields only modest rates of response and remission. Clearly, there is an urgent need to develop more effective treatment strategies for patients with MDD, One possible approach towards the development of novel pharmacotherapeuiic strategies for MDD involves identifying subpopulations of depressed patients who are more likely to experience the benefits of a given (existing) treatment versus placebo, or versus a second treatment. Attempts have been made to identify such “subpopulations, ” specifically by testing whether a given biological or clinical marker also serves as a moderator, mediator (correlate), or predictor of clinical improvement following the treatment of MDD with standard, first-line antidepressants. In the following article, we will attempt to summarize the literature focusing on several major areas (“leads”) where preliminary evidence exists regarding clinical and biologic moderators, mediators, and predictors of symptom improvement in MDD, Such clinical leads will include the presence of hopelessness, anxious symptoms, or medical comorbidity. Biologic leads will include gene polymorphisms, brain metabolism, quantitative electroencephalography, loudness dependence of auditory evoked potentials, and functional brain asymmetry

El trastorno depresivo mayor (TDM) es una enfermedad prevalente que está asociada frecuentemente con incapacidad, morbilidad y mortalidad significativas. A pesar del desarrollo y de la disponibilidad de numerosas opciones terapéuticas para el TDM, los estudios han mostrado que la monoterapia antidepresiva sólo produce bajas frecuencias de respuesta y remisión. Es claro que hay una urgente necesidad de desarrollar estrategias terapéuticas más efectivas para los pacientes con TDM, Una posible aproximación para el desarrollo de novedosas estrategias farmacoterapéuticas para el TDM implica identificar subpoblaciones de pacientes depresivos que con mayor probabilidad experimenten los beneficios de un tratamiento dado (existente) versus placebo, o versus un segundo tratamiento. Se han realizado intentas para identificar tales “subpoblaciones”, especificamente analizando si un determinado marcador biológico o clinico también sirve como un moderador, mediador (correlato) o predictor de la mejorfa clinica en el tratamiento del TDM con antidepresivos estándar de primera linea. En este articulo se intentará resumir la literatura focalizada en algunas áreas principales (“pistas”) donde existe evidencia preliminar relacionada con moderadores, mediadores y predictores clinicosy biológicos de mejorfa de sintomas en el TDM, Las pistas clinicas incluirán la presencia de desesperanza, sintomas ansiosos o comorbilidad médica. Las pistas biológicas incluirán polimorfismo genético, metabolismo cerebral, electroencefalografia cuantitativa, dependencia a la intensidad del volumen de los potenciales avocados auditives y asimetria cerebral funcional.

Le trouble dépressif majeur (TDM) est une pathologie prêvalente fréquemment associée à une invalidité, une morbidité et une mortalité significatives. Malgré le développement et l'existence de nombreux traitements pour le TDM, des études ont montré que les monothérapies antidépressives ne donnaient que de modestes taux de réponse et de rémission. Il devient vraiment urgent de développer des stratégies thérapeutiques efficaces pour les patients atteints de TDM, Une approche éventuelle pour un tel développement serait d'identifier des sous-populations de patients déprimés plus susceptibles de bénéficier d'un traitement donné (existant) versus placebo ou versus un second traitement. Des tentatives ont été menées afin d'identifier de telles « sous-populations », en vérifiant en particulier si un marqueur biologique ou clinique donné pouvaitt aussi servir de modérateur, médiateur (corrélat) ou prédicieur de l'amélioration clinique consécutive au traitement du TDM avec des antidépresseurs standard de première intention. Dans cet article, nous allons essayer de résumer la littérature dirigée vers plusieurs axes importants (« directeurs ») et pour lesquels il existe des arguments préliminaires en ce qui concerne les prédicteurs, médiateurs et modérateurs cliniques et biologiques de l'amélioration des symptômes du TDM, Ces symptômes cliniques « directeurs » incluront les symptômes de désespoir, d'anxiété ou de comorbidité médicale. Le polymorphisme génétique, le métabolisme cérébral, l'éleciroencéphalographie quantitative, la dépendance à l'intensité du son des potentiels évoqués auditifs et l'asymétrie cérébrale fonctionnelle feront partie des critères biologiques directeurs exposés.

Definitions

Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) is a prevalent illness that is frequently associated with significant disability, morbidity, and mortality. Results from the 2003 National Comorbidity Replication study found that the lifetime prevalence of MDD among American adults is 16.2%, ranking it among the most common and costly medical illnesses.Citation1 Despite the development and availability of numerous treatment options for MDD, studies have shown that antidepressant monotherapy yields only modest rates of response and remission. For example, a metaanalysisCitation2 of all double-blind placebo-controlled studies of antidepressants published since 1980 revealed response rates of 53% for antidepressants and 36% for placebo (absolute difference in response rate of 16.8%). Similarly, Petersen et alCitation3 report remission rates as low as 20% to 23% following each successive treatment among patients with MDD enrolled in one of two academically affiliated, depression-specialty clinics. In fact, only about. 50% of all patients enrolled ultimately achieved full remission of their depression. Similarly, only about one in three patients with MDD experienced a remission of their depression following treatment with the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) citalopram during the first level of the large, multicenter, Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) trial.Citation4 Clearly, there is an urgent need to develop safer, better-tolerated, and more effective treatments for MDD.

There are three major “paths” towards the development of novel pharmacotherapeutic strategies for MDD (Table I).Citation5 The first, approach involves developing new antidepressants to be used as monotherapy. A second approach involves combining pharmacologic agents, including established treatments (ie, established antidepressants), existing but not established agents, and new or novel agents. Finally, a third approach involves identifying subpopulations of depressed patients who are more likely to experience the benefits of a given (existing) treatment versus placebo, or versus a second treatment. Attempts have been made to identify such “subpopulations,” specifically by testing whether a given biological clinical marker also serves as a moderator, mediator (correlate), or predictor of clinical improvement following the treatment of MDD with standard, first-line antidepressants. A predictor of treatment (efficacy) outcome can involve factors (whether clinical or biologic), the presence or magnitude of which influences the likelihood of a particular outcome occurring during treatment. Efficacy outcomes in MDD commonly include either the resolution of depressive symptoms during treatment (the magnitude of reduction in depressive symptoms), the rapidity of response (the time course of symptom reduction), the attainment of a treatment response, or the attainment of symptom remission.

Table I Common pathways towards the development of more effective pharmacologic strategies for Major Depressive Disorder (MDD).

Differential predictors or moderators of efficacy outcome are a special subcategory of outcome predictors. Moderators of outcome involve factors (clinical or biologic), the presence or magnitude of which at baseline (immediately before treatment is initiated) influences the relative likelihood of a particular outcome occurring following treatment with one versus another agent. Thus, moderators of response can help predict differential efficacy between two or more treatments for MDD (for example, patients who present with a given moderator are more likely to respond to treatment with one antidepressant versus another than patients who do not present with that, given moderator).

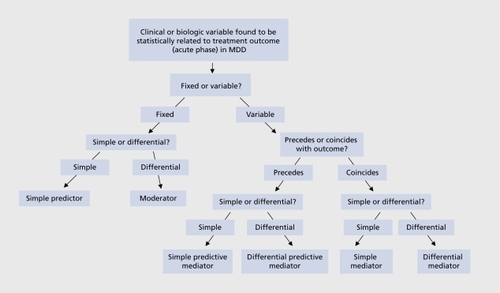

Mediators of efficacy outcome (sometimes also referred to as correlates) are measurable changes (usually biologic) that occur during treatment and correlate with treatment outcome. These changes can either precede (in which case they may also predict outcome - “predictive mediators”), or temporally coincide with treatment outcome (“simple mediators”). Differential mediators of outcome are also possible (changes that predict or correlate with an event, following treatment with one agent but not another). Figure 1 provides an overview regarding the combinations pertaining to mediators, moderators, and predictors of efficacy outcome in MDD. Table II outlines potential clinical, scientific, and treatment-development implications that may derive by identifying mediators, moderators, and predictors of efficacy outcome in MDD.

Table II Potential clinical, scientific and treatment development applications of predictors, moderators and mediators of treatment outcome in Major Depressive Disorder.

In the following paragraphs, we will attempt to summarize the literature focusing on several major areas (“leads”) where preliminary evidence exists regarding clinical and biologic moderators, mediators, and predictors of symptom improvement in MDD. In the first section, we will focus on clinical variables while, in the second section, on biological variables.

Clinical factors

To date, the overwhelming majority of published studies focusing on identifying predictors of response during the acute-phase of treatment of M'DD involve the SSRIs. These studies focus on examining the role of illness characteristics (ie, depressive subtype) or comorbidity (psychiatric (ie, axis I), characterologic (axis II), and medical (axis III), and will be reviewed according to antidepressant class.

SSRI treatment

In general, the presence and/or extent of factors associated with personality or temperament, including the presence of a Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)-defined personality disorder,Citation6-Citation9 neuroticism,Citation10 hypochondriacal concerns,Citation11 dysfunctional attitudes,Citation12 or temperamental styleCitation13 do not appear to predict response to the SSRIs.

In contrast, the presence and or degree of generalCitation14 as well as specific medical comorbidity, including hypercholesterolemia,Citation15 greater body weight,Citation16 other risk factors for vascular disease,Citation17,Citation18 hypofolatcmia,Citation18-Citation20 and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) white-matter hyperintensitiesCitation18,Citation21,Citation22 consistently appear to predict poorer outcome during the acute phase of treatment of MDD with the SSRIs, although other factors, such as the presence of mild hypothyroidismCitation23 and anemia,Citation24 do not.

The presence and severity of several symptoms of depression have also been linked to poorer prognosis, including hopelessness,Citation25 cognitive symptoms of depression including executive dysfunction,Citation26 physical symptoms of depression (somatic symptoms including pain, fatigue, physical symptoms of anxiety, and gastrointestinal symptoms),Citation27-Citation30 and psychomotor retardation.Citation27 Early improvement in depressive symptoms appears to also predict better outcome during the acute phase of treatment of MDD with fluoxetine, and vice versa.Citation31,Citation32

Illness features including greater chronicity,Citation7,Citation8 atypical depression,Citation7 depression with anger attacks,Citation7 or depression with comorbid attention deficity-hyperactivity disorder,Citation33 or insomniaCitation8,Citation34,Citation35 do not appear to confer a worse prognosis. However, greater MDD severity was found to predict a greater likelihood of attaining remission of depression following treatment with the SSRI escitalopram than several older SSRIs (fluoxetine, sertraline, paroxetine, citalopram) in MDD (moderator).Citation36

The presence of an anxious MDD subtype (defined using the “syndromal” approach as MDD presenting with at least one comorbid DSM anxiety disorder) was found to result, in poorer outcome during the acute phase of treatment of MDD with fluoxetineCitation7 but not sertraline.Citation8 Until recently, however, several relatively small studiesCitation9,Citation37-Citation40 defining anxious MDD using the “dimensional” approach (most commonly defined as a score of 7 or more on the anxiety-somatization subscale (HDRS-AS)Citation41 of the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS),Citation42 and have not confirmed earlier findings by Fava et al.Citation7 The HDRSAS subscale is comprised of the following HDRS items: psychic anxiety, somatic anxiety, somatic symptoms-gastrointestinal, somatic symptoms-general, hypochondriasis, and insight. Other studiesCitation37,Citation43,Citation44 which employ a scale different than the HDRS-AS to define anxious MDD (dimensional approach) have also not confirmed the findings of the earlier work by Fava et al.Citation7 However, recently, evidence stemming from Levels 1 and 2 of STAR*D do suggest significantly lower remission rates following the treatment of MDD with either first-line (citalopram) or second-line treatment strategies (switching to antidepressants versus augmentation or combination strategies).Citation45

Most of the studies described above examining the potential role of several factors as possible predictors of outcome following the acute phase of treatment of MDD with an SSRI share two major limitations: (i) most involve a relatively small sample size, resulting in limited statistical power to detect an effect of a factor on treatment, outcome; and (ii) most involve analyses conducted in either univariate or bivariate fashion (ie, simply controlling for overall depression severity at baseline). More recently, Trivedi et alCitation4 conducted multivariate analyses in STAR*D, examining potential predictors of response to open-label citalopram (up to 60 mg, up to 14 weeks of treatment) in MDD utilizing a datasct of unprecedented statistical power (n=2876). Variables examined as potential predictors of outcome included several demographic (ie, age, gender, race, sociodemographic variables) and clinical (age of onset of MDD, duration of episode, the presence of psychiatric and medical comorbidity) factors. Participants who were Caucasian, female, employed, or had higher levels of education or income had higher chances of success. Longer depressive episodes, more concurrent psychiatric disorders (especially anxiety disorders and or drug abuse) and general medical disorders, and lower baseline psychosocial functioning and quality of life were associated with poorer chances of success.

Treatment with older agents (TCAs and MAOIs)

In general, results of these studies parallel those focusing on the use of SSRIs in MDD.

While the results of two studies suggest, that the presence of a comorbid personality disorder confers an increased risk of poor outcome during the treatment, of MDD with the tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs),Citation46,Citation47 the majority of studies do not. support this relationship.Citation8,Citation48-Citation55 However, two studies do report poorer outcome among MDD patients with than without a comorbid cluster C personality disorder during TCA treatment.Citation53-Citation56

Several studies do not report the presence of neuroticism to predict antidepressant response following TCA treatment in MDD.Citation50-Citation52,Citation55 The interactions of certain elements of temperament, (novelty seeking, harm avoidance, and reward dependence) were found to help predict response to TCAs in one,Citation50 but not a subsequent, study.Citation57

Symptom chronicity was found to result in poor outcome during treatment of MDD with the TCAs in one,Citation52 but not. a second study.Citation8 Finally, specific symptoms including insomniaCitation8,Citation35 and suicidal ideationCitation58 do not appear to predict response to TCA treatment. However, the presence of somatic symptoms of depression,Citation59 elevated cholesterol levels,Citation60 but. not the presence and/or extent of medical comorbidityCitation61 have been linked to lower chances of responding to the TCA nortriptyline in MDD.

Although earlier studies had suggested that patients with anxious MDD may respond more poorly to treatment with the TCAs and/or monamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs),Citation62-Citation64 a number of studies did not find a significant relationship between the presence of an anxious MDD subtype and poorer outcome following treatment with an MAOICitation65-Citation70 or TCA.Citation9,Citation38,Citation40,Citation48,Citation65-Citation70 .Finally, the presence of atypical MDD has been shown to predict a greater likelihood of clinical response to treatment with the M AOI phenelzine than the TCA imipramine.Citation69,Citation71

Treatment with newer agents

Only a handful of studies specifically focus on identifying predictors of acute-phase outcome (efficacy) during the treatment of MDD with newer agents. Nelson and CloningerCitation72 reported the interaction of several temperamental factors, including reward dependence and harm avoidance, to predict response to the serotonin (5HT2-receptor antagonist ncfazodone in MDD (n=18). This was confirmed shortly thereafter using a larger database (n=1119).Citation73 However, the predictive power of neuroticism in the latter study accounted for a trivial 1.1% of the total variance in outcome, raising questions regarding the clinical relevance of this finding.

Rush et alCitation43,Citation41,Citation74 did not find the presence of pretreatment anxiety or insomnia to confer a better or poorer prognosis during treatment with the noradrenaline-dopamine reuptake inhibitor (NDRI) bupropion. However, a more recent, analysis involving 10 randomized, double-blind clinical trials comparing bupropion with an SSRI for MDD did reveal a greater likelihood of clinical response following treatment, with an SSRI than bupropion among patients with anxious MDD (moderator).Citation75

Sir et alCitation39 and Davidson et alCitation76 did not find that, the presence of an anxious subtype of MDD or anxious symptoms in MDD had influenced the likelihood of responding to venlafaxine in MDD, although Silverstone and SalinasCitation77 found a slower onset of antidepressant effects among venlafaxinc-trcated patients with MDD and comorbid generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) than those without, comorbid GAD, and patients with anxious depression, as defined by elevated scores on the HDRSAS scale, were significantly less likely to remit, following venlafaxine treatment in Level 2 of STAR*D.Citation45 However, postmenopausal women with MDD who were not on hormone-replacement therapy were found to be much more likely to attain remission of MDD following treatment with the serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) venlafaxine than an SSRI than either premenopausal women or postmenopausal women on hormone replacement therapy in one study.Citation78

Kornstein et alCitation79 did not find either age nor gender to influence efficacy outcome following treatment with the SNRI duloxetine. Mallinckrodt et alCitation80 did not find the presence of a melancholic subtype to influence efficacy outcome following treatment with duloxetine. However, greater MDD severity was found to predict a greater likelihood of attaining remission of depression following treatment with the SNRI duloxetine than the SSRIs fluoxetine and paroxetine in MDD (moderator).Citation81

Biologic factors

To date, numerous studies have explored several potential genetic markers of outcome during the acute phase of treatment of MDD. The majority of these studies stem from one of two fields: genetics and neurophysiology. Due to the paucity of reports focusing on non-SSRI agents, biologic factors will be reviewed according to field (ie, genetics versus neurophysiology) rather than class (ie, SSRI versus non-SSRI treatment).

Genetic markers

A number of reports explore various genetic markers as predictors of clinical response to antidepressants in MDD. The vast majority of these focus on genes coding for proteins directly involved in the monoaminergic system, including tryptophan hydroxylase (TPH - the rate -limiting step in serotonin synthesis), the serotonin transporter (5-HTT),the serotonin 5-HT-2 receptors, the monoamine oxidase enzyme (MAO), and the catechol-O-methyltransf erase enzyme (COMT). The overwhelming majority of these studies involve treatment with the SSRIs.

SSRIs

Three studies suggest that patients with a specific polymorphism (A218C) in the gene coding for the TPH enzyme may respond more poorly to SSRIs than those without such a polymorphism,Citation82-Citation84 although this was not confirmed in three other studies.Citation85-Citation88 Early on, the results of someCitation88-Citation98 but not allCitation99 Citation103 studies also suggested that depressed patients with a certain (insertion/deletion) polymorphism located in the promoter region of the gene coding for the serotonin transporter (5 HTTPR) have a relatively poorer response to the SSRIs than those without. Several pooled analyses and meta-analyses have subsequently confirmed a predictive role for 5HTTPR genotype with regards to SSRI response in MDD, more so for Caucasian than Asian patients.Citation104-Citation106 More recently, however, Kraft, et alCitation107 and, subsequently, Hu et alCitation108 did not find an association between response to the SSRI citalopram and 5 HTTPR genotype among 1914 subjects who participated in the first level of the STAR*D trial. This report, provides the strongest, evidence to date against a role for variation at this gene as a factor predicting clinical response to the SSRIs.

Similarly, there have been conflicting reports regarding the role of 5-HT2-receptor genotype as a predictor of SSRI response. Specifically, two studies have identified a specific single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in the promoter region of the 5-HT2 receptor (A1438G) that appears to predict response to the SSRIs in MDD.Citation91,Citation109 However, this finding was not confirmed in a third report.Citation110 More recently, however, McMahon et alCitation111 conducted an analysis of numerous candidate genes as potential predictors of response to open-label citalopram in MDD utilizing the STAR*D level-1 dataset (n=1953). Of 68 candidate genes investigated, only genetic variation at the locus coding for the 5-HT7 receptor gene was found to consistently predict clinical outcome,Citation111 with differences in genotype (comparison of two homozygous groups) accounting for an 18% difference in the absolute risk of having no response to treatment.

Relatively fewer studies have focused on genes coding for proteins not directly related to the monoaminergic system. Using a STAR*D-based dataset, Pcrlis et alCitation112 demonstrated a relationship between the presence of a variant (KCNK2) in a gene (TREK1) coding for a potassium channel and the likelihood of experiencing symptom improvement, following treatment of MDD with the SSRI citalopram. In a separate study, Paddock et alCitation113 reported that genetic variation in a kainic acid-type glutamate receptor was associated with response to the antidepressant citalopram (marker (rsl954787) in the GRIK4 gene, which codes for the kainic acid-type glutamate receptor KA1). There is also a STAR*D-based report, suggesting a relationship between the likelihood of achieving remission of symptoms during treatment with the SSRI citalopram and genotype at. one of the markers (rs4713916) in the FKBP5 gene, a protein of the hypothalamic-pituitary adrenal (HPA) system modulating the glucocorticoid receptor.Citation114

Other agents

Studies looking at genetic markers as predictors of response to other antidepressants are few. The results of one study report 5HTTPR genotype to influence the likelihood of responding to the tricyclic antidepressant (TCA) nortriptyline in MDDCitation115 although this could not be replicated in a separate study.Citation99 Two separate studies report. 5HTTPR genotype to predict response to the SNRI venlafaxine,Citation116 and the 5-HT2 alpha-2 adrenergic receptor inhibitor mirtazapine.Citation117 Finally, there is also a single study examining the role of MAO-A genotype as a predictor of clinical response to the MAOI moclobemide; no relationship was found.Citation118

Reports from studies comparing agents of different classes

Reports examining for genetic predictors of response from randomized, double-blind clinical trials comparing two antidepressants of different classes are few Although preliminary, such studies can be useful in genetic markers that may serve as moderators of treatment, efficacy. Joyce et alCitation119 studied 169 MDD patients randomized to treatment with either fluoxetine or nortriptyline, and examined whether 5HTTPR or G-protein beta3-subunit (C825T) genotype influenced symptom improvement, following treatment with either of these two agents. For patients younger than 25 years of age, the T allele of the G protein beta3 subunit, was associated with a poorer response to nortriptyline. There was no relationship between 5HTTPR genotype and response to treatment with either antidepressant among this age group, nor was there any relationship between G protein beta3 subunit genotype status and response to paroxetine. Among patients 25 years of age or older, however, 5HTTPR genotype predicted response to both fluoxetine and nortriptyline. Findings stemming from this report have yet to be replicated. Similarly, Szegcdi et alCitation120 studied the relationship between the COMT (vall58met) polymorphism status and antidepressant response following treatment with paroxetine versus mirtazapine (5-HT2-alpha-2 adrenergic receptor antagonist) in MDD. Patients homozygous for COMT-met showed a poorer response to mirtazapine than patients with other genotypes. A similar finding was not observed during paroxetine treatment. Preliminary findings from these two trials have yet to be prospectively confirmed.

Neurophysiology

Brain functioning and metabolism

A number of studies have examined the potential relationship between functional changes, including changes in regional blood glucose metabolism as measured by positron emission tomography (PPT), and clinical response following the treatment of MDD with standard antidepressants. Mayberg,Citation121,Citation122 for instance, studied the relationship between regional metabolic changes in the central nervous system (CNS) and clinical response following a 6-week trial of the SSRI fluoxetine for MDD. The results of her work suggest, that metabolism in certain brain areas, as measured by PET, may serve as a mediator of response to the SSRIs. Specifically, she found an increase in brain stem and dorsal cortical metabolism (prefrontal, parietal, anterior cingulatc, and posterior cingulate), and a decrease in limbic and striatum metabolism (subgenual cingulate, hippocampus, insula, and palladium) from week 1 to week 6 of treatment among fluoxetine responders. Fluoxetine nonrcsponders did not demonstrate changes in these areas during the same treatment period (weeks 1-6). Similarly, Tosifescu et alCitation123 established a relationship between normalization in measures of brain biocnergetic metabolism among patients with SSRI-resistant MDD who experienced symptom improvement (clinical response) following T3 augmentation of their SSRI treatment, regimen.

In a recent work, Mayberg et alCitation121 reviewed earlier studies examining the relationship between regional metabolic changes and symptom improvement during the treatment of MDD with antidepressants, and concluded that a significant correlation between normalization of frontal hypometabolism and clinical improvement was the best-replicated finding. However, a similar relationship (ie, between an increase in frontal metabolism and symptom improvement) was also reported during placebo treatment.Citation121 The results of the latter study suggest that such changes, at least as detected by the technology available at the time, appear to be related to nonspecific (placebo) rather than specific (drug) treatment effects and, therefore, may not serve as robust differential treatment mediators. Little et al,Citation124 for instance, examined whether there are differences in the relationship between brain metabolism at baseline (predictor or moderator) and symptom improvement between two antidepressants of different class (the NDRI bupropion versus the SNRI venlafaxine). For the most part, similar findings predicted symptom improvement for both agents (frontal and left temporal hypometabolism), although some differences emerged (compared with control subjects, bupropion responders (n = 6) also had cerebellar hypermetabolism, whereas venlafaxine responders showed bilateral temporal and basal ganglia hypometabolism). This study has yet to be replicated, either with regards to baseline brain metabolism (ie, moderator of response), or changes in baseline brain metabolism (ie, mediator of response).

Quantitative EEG

Quantitative electroencephalography (QEEG) involves the use of computer software analysis to deconstruct, electroencephalographic (EEG) tracings and quantify parameters including frequency and amplitudes (traditional EEG involves manual readings). A relevant measurement, generated by the software traditionally employed by QEEG is called cordance, which involves a combination of absolute power (the power of a frequency band) and relative power (the percentage of power in a frequency band compared with the total power across all frequency bands).Citation125,Citation126 Cordance of frontal EEG measurements in the theta band (4 to 8Hz) has consistently been found to correlate with antidepressant response in M'DD. Specifically, the result of several studies suggest a decrease in theta cordance from prefrontal EEG leads during the first, week of treatment, with either an SSRI, an SNRI, or a variety of antidepressants, to predict, greater symptom improvement, following 4 to 10 weeks of treatment.Citation127-Citation129 In contrast, an increase in prefrontal theta cordance during the first week of treatment was demonstrated among placeboresponders, suggesting that prefrontal theta cordance may serve as a differential (predictive) mediator of response to antidepressants versus placebo.Citation130 Interestingly enough, a report by Hunter et alCitation131 suggests that the decrease in prefrontal EEG theta cordance during the week immediately preceding the initiation of treatment of MDD with antidepressants (fluoxetine, venlafaxine) or placebo (placebo lead-in period) is related to the likelihood of responding to antidepressants but not placebo following 9 weeks of treatment (moderator of response). Thus, the sum of the evidence reviewed above suggests a potential role for the change in prefrontal theta EEG cordance during the first week of treatment in MDD as a mediator and predictor of response to antidepressants but not placebo (differential mediator). Although the exact physiologic relevance of this probable treatment mediator is, at present, unclear, several lines of evidence suggest it may serve as a proxy for changes in underlying prefrontal cortex metabolism (see ref 127 for further details).

Loudness dependence of auditory evoked potentials

Much less is known regarding the potential predictive ability of other EEG-related biomarkers. Loudness dependence of auditory evoked potentials (LDAEP) is one such measurement, derived from EEG recordings thought to correspond to the primary auditory cortex following the administration of an auditory stimulus.Citation125 A “strong” LDAEP suggests that the characteristics of evoked potentials following an auditory stimulus are highly dependent on the intensity (loudness) of the auditory stimulus.Citation134 In contrast, a “weak” LDAEP suggests that evoked potentials following an auditory stimulus do not vary much as a function of how loud the sound is.Citation132 To date, a variety of clinical studies have demonstrated that patients with “strong” LDAEP at baseline are more likely to respond to treatment with SSRIs than those with “weak” LDEAP.Citation133-Citation137 However, in a small (n=35) randomized, open-label trial comparing the SSRI citalopram with the norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (NRI) reboxetine for MDD, patients with ”strong“ LDAEP were more likely to respond to citalopram than reboxetine while patients with ”weak“ LDAEP were more likely to response to reboxetine than citalopramCitation138 (differential predictor or moderator of response). Doubleblind, randomized clinical trials involving treatment with antidepressants of different class (ie, SSRI versus NRI) which are specifically designed to examine any potential moderating effects of LDAEP (ie, randomization based on LDAEP status would also need to occur) have yet to be conducted.

Brain functional asymmetry (dichotic listening)

Dichotic listening tasks involve auditory stimuli being presented to both the left and the right ear. Potential differences in perception (perceptual asymmetry) are then used as a proxy for brain functional asymmetry. Brader et alCitation140 first studied the relationship between the presence of perceptual asymmetry following dichotic listening tasks at baseline and symptom improvement following treatment with the TCAs. A left-car (right hemisphere) advantage was significantly more common among nonresponders than responders. This was replicated for fluoxetine (SSRI) treatment in two different studiesCitation140,Citation141 and bupropion (NDRI) treatment in a separate study.Citation142

Conclusion

A number of potential clinical predictors of symptom improvement, during the pharmacologic treatment of MDD have been identified to date, mostly from studies focusing on the acute phase of treatment of MDD with the SSRIs. These include the presence of a greater number of concurrent psychiatric disorders (especially anxiety disorders), or general medical disorders (ie, cardiovascular illness, hypofolatemia).The presence of or more of these factors should alert clinicians to alter their treatment approach in order to help optimize the chances of patients recovering from depression. For instance, clinicians may chose to initiate therapy with two treatments, ie, pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy, schedule more frequent follow-up visits, increase the dose sooner in treatment nonresponders, or resort to various switching, augmentation, or combination strategies sooner for patients who do not experience a sufficient improvement in symptoms. Several potential clinical mediators of response have also been identified including the presence of severe MDD (escitalopram and duloxetine versus “older” SSRIs), anxious M..DD (bupropion versus SSRIs), atypical MDD (MAOIs versus TCAs), and hormonal status among women (venlafaxine versus “older” SSRIs). However, at the present time, such “leads” are preliminary and have not been prospectively confirmed in randomized, double-blind clinical trials. Finally, preliminary studies have identified a number of putative “biomarkers,” relating to genetic or neurophysiologic (particularly quantitative EEG (QEEG)-based measurements as well as measures of prefrontal cortical metabolism), which appear to correlate with symptom improvement during the treatment of MDD with standard antidepressants (mediators of response). Conducting further studies designed to establish reliable, replicable, and robust biological factors which function as predictors, mediators, or moderators of clinical improvement in MDD could benefit, the field in several ways, from enhancing our ability to develop more effective treatments to improving our ability to choose an individualized pharmacotherapeutic regimen for patients with MDD which would result in a more rapid and robust resolution of depressive symptoms.

Selected abbreviations and acronyms

| 5-HT | = | serotonin |

| DSM | = | Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders |

| EEG | = | electroencephalogram |

| HDRS | = | Hamilton Depression Rating Scale |

| LDAEP | = | loudness dependence of auditory evoked potentials |

| MAOI | = | monoamine oxidase inhibitor |

| MDD | = | Major Depressive Disorder |

| SSRI | = | selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor |

| STAR*D | = | Sequenced Alternatives to Relieve Depression |

| TCA | = | tricyclic antidepressant |

REFERENCES

- KesslerRC.BerglundP.DernierO.et alThe epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R)JAMA.20032893095310512813115

- PapakostasGI.FavaM.Does the probability of receiving placebo influence the likelihood of responding to placebo or clinical trial outcome? A meta-regression of double-blind, randomized clinical trials in MDDNeuropsychopharmacology.200631(s1)s158

- PetersenT.PapakostasGI.PosternakMA.et alEmpirical testing of two models for staging antidepressant treatment resistanceJ Clin Psychopharmacoi.200525336341

- TrivediMH.RushAJ.WisniewskiSR.et alSTAR*D Study TeamEvaluation of outcomes with citalopram for depression using measurement-based care in STAR*D: implications for clinical practiceAm J Psychiatry.2006163284016390886

- PapakostasGl.Augmentation strategies in the treatment of MDD: examining the evidence involving the use of atypical antipsychotic agentsCNSSpectr.200712(12 suppl 22)1012

- FavaM.BouffidesE.PavaJA.McCarthyMK.SteingardRJ.RosenbaumJF.Personality disorder comorbidity with major depression and response to fluoxetine treatmentPsychother Psychosom.1994621601677846259

- FavaM.UebelackerLA.AlpertJE.NierenbergAA.PavaJA.RosenbaumJF.Major depressive subtypes and treatment responseBiol Psychiatry.1997425685769376453

- HirschfeldRM.RussellJM.DelgadoPL.et alPredictors of response to acute treatment of chronic and double depression with sertraline or imipramineJ Clin Psychiatry.1998596696759921701

- RussellJM.KoranLM.RushJ.et alEffect of concurrent anxiety on response to sertraline and imipramine in patients with chronic depressionDepress Anxiety.200113182711233456

- PetersenT.PapakostasGl.BottonariK.et alNEO-FFI factor scores as predictors of response to fluoxetine treatment in depressed outpatientsPsychiatry Res.200210991611850046

- DemopulosC.FavaM.McLeanNE.AlpertJE.NierenbergAA.RosenbaumJF.Hypochondriacal concerns in depressed outpatientsPsychosomatMed.199658314320

- FavaM.BlessE.OttoMW.PavaJA.RosenbaumJF.Dysfunctional attitudes in major depression. Changes with pharmacotherapyJ Nerv Ment Dis.199418245498277301

- NewmanJR.EwingSE.McCollRD.et alTridimensional personality questionnaire and treatment response in major depressive disorder: a negative studyJ Affect Disord.20005724124710708838

- losifescuDV.NierenbergAA.AlpertJE.et alThe impact of medical comorbidity on acute treatment in major depressive disorderAm J Psychiatry.20031602122212714638581

- SonawallaS.PapakostasGl.PetersenT.et alElevated cholesterol levels in major depressive disorder associated with non-response to fluoxetine treatmentPsychosomatics.20024331031612189257

- PapakostasGl.PetersenT.losifescuDV.et alObesity among outpatients with major depressive disorderInt J Neuropsychopharmacol.200471514720317

- losifescuDV.Clementi-CravenN.FraguasR.et alCardiovascular risk factors may moderate pharmacological treatment effects in major depressive disorderPsychosomatMed.200567703706

- PapakostasGl.losifescuDV.RenshawPF.et alBrain MRI white matter hyperintensities, cardiovascular risk factors, and one-carbon cycle metabolism in non-geriatric outpatients with major depressive disorder (Part II)Psychiatry Res: Neuroimag.2005140301307

- FavaM.BorusJS.AlpertJE.NierenbergAA.RosenbaumJF.BottiglieriT.Folate, vitamin B12, and homocysteine in major depressive disorderAm J Psychiatry.19971544264289054796

- PapakostasGl.PetersenT.LebowitzBD.etal.The relationship between serum folate, vitamin B12 and homocysteine levels in major depressive disorder and the timing of clinical improvement to fluoxetineInt J Neuropsychopharmacol.2005852352815877935

- losifescuDV.RenshawPF.LyooIK.et alBrain MRI white matter hyperintensities, cardiovascular risk factors, and treatment outcome in major depressive disorderBr J Psychiatry.200618818018516449707

- AlexopoulosGS.MurphyCF.Gunning-DixonFM.et alMicrostructural white matter abnormalities and remission of geriatric depressionAm J Psychiatry.200816523824418172016

- FavaM.LabbateLA.AbrahamME.RosenbaumJF.Hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism in major depression revisitedJ Clin Psychiatry.1995561861927737957

- MischoulonD.BurgerJK.SpillmannMK.WorthingtonJJ.FavaM.AlpertJE.Anemia and macrocytosis in the prediction of serum folate and vitamin B12 status, and treatment outcome in major depressionJ Psychosomat Res.200049183187

- PapakostasGl.PetersenT.PavaJ.et alHopelessness as a predictor of non-response to fluoxetine in major depressive disorderAnn Clin Psychiatry.2007195817453655

- AlexopoulosGS.KiossesDN.HeoM.MurphyCF.ShanmughamB.Gunning-DixonFExecutive dysfunction and the course of geriatric depressionBiol Psychiatry.20055820421016018984

- BurnsRA.LockT.EdwardsDR.et alPredictors of response to aminespecific antidepressantsJ Affect Disord.199535971068749837

- DenningerJW.PapakostasGl.MahalY.et alSomatic symptoms in outpatients with major depressive disorder treated with fluoxetinePsychosomatics.20064734835216844895

- PapakostasGl.PetersenT.losifescuDV.AlpertJE.NierenbergAA.FavaM.Somatic symptoms as predictors of time to onset of response to fluoxetine in major depressive disorderJ Clin Psychiatry.2004554354615119918

- PapakostasGl.McGrathPJ.StewartJ.et alPsychic and somatic anxiety symptoms as predictors of response to fluoxetine in major depressive disorderPsychiatry Res.200816111612018755514

- NierenbergAA.McLeanNE.AlpertJE.WorthingtonJJ.RosenbaumJF.FavaM.Early nonresponse to fluoxetine as a predictor of poor 8-week outcomeAm J Psychiatry.1995152150015037573590

- NierenbergAA.FarabaughAH.AlpertJE.et alTiming of onset of antidepressant response with fluoxetine treatmentAm J Psychiatry.20001571423142810964858

- AlpertJE.MaddocksA.NierenbergAA.O'SullivanR.et alAttention deficit hyperactivity disorder in childhood among adults with major depressionPsychiatry Res.1996622132198804131

- FavaM.HoogSL.JudgeRA.KoppJB.NilssonME.GonzalesJS.Acute efficacy of fluoxetine versus sertraline and paroxetine in major depressive disorder including effects of baseline insomniaJ Clin Psychopharmacoi.200222137147

- SimonGE.HeiligensteinJH.GrothausL.KatonW.RevickiD.Should anxiety and insomnia influence antidepressant selection: a randomized comparison of fluoxetine and imipramineJ Clin Psychiatry.19985949559501885

- KennedySH.AndersenHF.LamRW.Efficacy of escitalopram in the treatment of major depressive disorder compared with conventional selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and venlafaxine XR: a meta-analysisJ Psychiatry Neurosci.200631122131 16575428

- FeigerAD.FlamentMF.BoyerP.GillespieJA.Sertraline versus fluoxetine in the treatment of major depression: a combined analysis of five double-blind comparator studiesInt Clin Psychopharmacoi.200318203210

- LenzeEJ.MulsantBH.DewMA.et alGood treatment outcomes in late-life depression with comorbid anxietyJ Affect Disord.20037724725414612224

- SirA.D'SouzaRF.UguzS.et alRandomized trial of sertraline versus venlafaxine XR in major depression: efficacy and discontinuation symptomsJ Clin Psychiatry.2005661312132016259546

- TollefsonGD.HolmanSL.SaylerME.PotvinJH.Fluoxetine, placebo, and tricyclic antidepressants in major depression with and without anxious featuresJ Clin Psychiatry.19945550598077155

- ClearyP.GuyW.Factor analysis of the Hamilton Depression ScaleDrugs Exp CliniRes.19771115120

- HamiltonM.A rating scale for depressionJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry.196023566214399272

- RushAJ.TrivediMH.CarmodyTJ.et alResponse in relation to baseline anxiety levels in major depressive disorder treated with bupropion sustained release or sertralineNeuropsychopharmacology,20012513113811377926

- RushAJ.BateySR.DonahueRMJ.AscherJA.CarmodyTJ.MetzA.Does pretreatment anxiety predict response to either bupropion SR or sertraline?J Affect Disord.2001 64818711292522

- FavaM.RushAJ.AlpertJE.et alDo Outpatients with anxious vs. nonanxious major depressive disorder have different treatment outcomes? A STAR*D ReportAm J Psychiatry.2008165342351 18172020

- PatienceDA.McGuireRJ.ScottAI.FreemanCP.The Edinburgh Primary Care Depression Study: personality disorder and outcomeBr J Psychiatry.19951673243307496640

- ReichJH.Effect of DSM-III personality disorders on outcome of tricyclic antidepressant-treated nonpsychotic outpatients with major or minor depressive disorderPsychiatry Res.1990321751812367602

- FriedmanRAParidesMBaffRMoranMKocsisJHPredictors of response to desiprarnine in dysthymiaJ Clin Psychopharmacoi.199515280283

- JoffeRT.ReganJJ.Personality and response to tricyclic antidepressants in depressed patientsJ Nerv Ment Dis.19891777457492592964

- JoycePR.MulderRT.CloningerCR.Temperament predicts clomipramine and desiprarnine response in major depressionJ Affect Disord.19943035468151047

- KocsisJH.MasonBJ.FrancesAJ.SweeneyJ.MannJJ.MarinD.Prediction of response of chronic depression to imipramineJ Affect Disord.1989172552602529294

- Mynors-WallisL.GathD.Predictors of treatment outcome for major depression in primary carePsychol Med.1997277317369153693

- PapakostasGl.PetersenT.FarabaughA.et alPsychiatric comorbidity among responders and nonresponders to nortriptyline in treatment-resistant major depressive disorderJ Clin Psychiatry.2003641357136114658951

- SheaMT.PilkonisPA.BeckhamE.et alPersonality disorders and treatment outcome in the NIMH Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research ProgramAm J Psychiatry.19901477117182343912

- ZuckermanDM.PrusoffBA.WeissmanMM.PadianNS.Personality as a predictor of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy outcome for depressed outpatientsJ Consult Clin Psychol.1980487307357440829

- PeselowED.FieveRR.DiFigliaC.Personality traits and response to desiprarnineJ Affect Disord.1992242092161578076

- SatoT.HiranoS.NaritaT.etal.Temperament and character inventory dimensions as a predictor of response to antidepressant treatment in major depressionJ Affect Disord.19995615316110701472

- PapakostasGl.PetersenT.PavaJ.et alHopelessness and suicide in treatment-resistant depression: prevalence and impact on treatment outcomeJ Nerv Ment Dis.200319144444912891091

- PapakostasGl.PetersenT.DenningerJ.et alSomatic symptoms in treatment-resistant depressionPsychiatry Res.2003118394512759160

- PapakostasGl.PetersenT.SonawallaS.et alSerum cholesterol in treatment-resistant depressionNeuropsychobiology.20034714615112759558

- PapakostasGl.PetersenT.losifescuDV.et alAxis III co-morbidity in treatment-resistant depressionPsychiatry Res.200311818318812798983

- FlintAJ.RifatSL.Anxious depression in elderly patients. Response to antidepressant treatmentAm J Geriatr Psychiatry,199751071159106374

- GrunhausL.RabinD.GredenJF.Simultaneous panic and depressive disorder: response to antidepressant treatmentsJ Clin Psychiatry.198647473941058

- GrunhausL.HarelY.KruglerT.PandeAC.HaskettRF.Major depressive disorder and panic disorder. Effects of comorbidity on treatment outcome with antidepressant medicationsClin Neuropharmacol.1988114544613219677

- AngstJ.ScheideggerP.StablM.Efficacy of moclobemide in different patient groups. Results of newsubscales of the Hamilton Depression Rating ScaleClin Neuropharmacol.199316 (suppl)2S55S628313398

- Delini-StulaA.MikkelsenH.AngstJ.Therapeutic efficacy of antidepressants in agitated anxious depression - a meta-analysis of moclobemide studiesJ Affect Disord.19953521308557884

- LiebowitzMR.QuitkinFM.StewartJW.et alAntidepressant specificity in atypical depressionArch Gen Psychiatry.1988451291373276282

- QuitkinFM.StewartJW.McGrathPJ.et alPhenelzine versus imipramine in the treatment of probable atypical depression: defining syndrome boundaries of selective MAOI respondersAm J Psychiatry.19881453063113278631

- QuitkinFM.McGrathPJ.StewartJW.et alAtypical depression, panic attacks, and response to imipramine and phenelzine. A replicationArch Gen Psychiatry.1990479359412222132

- RobinsonDS.KayserA.CorcellaJ.LauxD.YinglingK.HowardD.Panic attacks in outpatients with depression: response to antidepressant treatmentPsychopharmacoi Bull.198521562567

- QuitkinFM.HarrisonW.StewartJW.et alResponse to phenelzine and imipramine in placebo nonresponders with atypical depression. A new application of the crossover designArch Gen Psychiatry.1991483193232009033

- NelsonEC.CloningerCR.The tridimensional personality questionnaire as a predictor of response to nefazodone treatment of depressionJ Affect Disord.19953551578557887

- NelsonECloninger.CRExploring the TPQ as a possible predictor of antidepressant response to nefazodone in a large multi-site studyJ Affect Disord.1997441972009241580

- RushAJ.CarmodyTJ.HaightBR.RockettCB.ZisookS.Does pretreatment insomnia or anxiety predict acute response to bupropion SR?Ann Clin Psychiatry.2005171915941026

- PapakostasGl.StahlSM.KrishenA.et alEfficacy of bupropion and the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in the treatment of major depressive disorder with high levels of anxiety (anxious depression)J Clin Psychiatry.2008691287129218605812

- DavidsonJR.Meoni P, Haudiquet V, Cantillon M, Hackett D. Achieving remission with venlafaxine and fluoxetine in major depression: its relationship to anxiety symptomsDepress Anxiety.20021641312203668

- SilverstonePH.SalinasE.Efficacy of venlafaxine extended release in patients with major depressive disorder and comorbid generalized anxiety disorderJ Clin Psychiatry.20016252352911488362

- Thase MEEntsuah R.Cantillon MKornstein SG.Relative antidepressant efficacy of venlafaxine and SSRIs: sex-age interactionsJ Womens Health.200514609616

- KornsteinSG.WohlreichMM.MallinckrodtCH.WatkinJG.StewartDE.Duloxetine efficacy for major depressive disorder in male vs. female patients: data from 7 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trialsJ Clin Psychiatry.20066776177016841626

- MallinckrodtCH.WatkinJG.LiuC.WohlreichMM.RaskinJ.Duloxetine in the treatment of Major Depressive Disorder: a comparison of efficacy in patients with and without melancholic featuresBioMed Central Psychiatry,20055115631624

- ThaseME.PritchettYL.OssannaMJ.SwindleRW.XuJ.DetkeMJ.Efficacy of duloxetine and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: comparisons as assessed by remission rates in patients with major depressive disorderJ Clin Psychopharmacoi.200727672676

- HamBJ.LeeBC.PaikJW.et alAssociation between the tryptophan hydroxylase-1 gene A218C polymorphism and citalopram antidepressant response in a Korean populationProgr Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry.200731104107

- SerrettiA.ZanardiR.RossiniD.CusinC.LilliR.SmeraldiE.Influence of tryptophan hydroxylase and serotonin transporter genes on fluvoxamine antidepressant activityMol Psychiatry.2001658659211526473

- SerrettiA.ZanardiR.CusinC.RossiniD.LorenziC.SmeraldiE.Tryptophan hydroxylase gene associated with paroxetine antidepressant activityEurop Neuropsychopharmacology,200111375380

- HongCJ.ChenTJ.YuYW.TsaiSJ.Response to fluoxetine and serotonin 1A receptor (C-1019G) polymorphism in Taiwan Chinese major depressive disorderPharmacogenomics J.20066273316302021

- KatoM.FukudaT.WakenoM.et alEffects of the serotonin type 2A, 3A and 3B receptor and the serotonin transporter genes on paroxetine and fluvoxamine efficacy and adverse drug reactions in depressed Japanese patientsNeuropsychobiology.20065318619516874005

- YoshidaK.NaitoS.TakahashiH.et alMonoamine oxidase: A gene polymorphism, tryptophan hydroxylase gene polymorphism and antidepressant response to fluvoxamine in Japanese patients with major depressive disorderProgr Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry.20022612791283

- AriasB.CatalanR.GastoC.GutierrezB.FananasL.5-HTTLPR polymorphism of the serotonin transporter gene predicts non-remission in major depression patients treated with citalopram in a 12-weeks follow up studyJ Clin Psychopharmacoi.200323563567

- DurhamLK.WebbSM.MilosPM.ClaryCM.SeymourAB.The serotonin transporter polymorphism, 5HTTLPR, is associated with a faster response time to sertraline in an elderly population with major depressive disorderPsychopharmacology.200417452552912955294

- BozinaN.PelesAM.SagudM.BilusicH.JakovljevicM.Association study of paroxetine therapeutic response with SERT gene polymorphisms in patients with major depressive disorderWorld J Biol Psychiatry.2008919019717853254

- KatoM.WakenoM.OkugawaG.FukudaT.AzumaJ.KinoshitaT.SerrettiA.No association of TPH1 218A/C polymorphism with treatment response and intolerance to SSRIs in Japanese patients with major depressionNeuropsychobiology.20075616717118332644

- KronenbergS.ApterA.BrentD.Serotonin transporter polymorphism (5-HTTLPR) and citalopram effectiveness and side effects in children with depression and/or anxiety disordersJ Child Adolescent Psychopharmacoi.200717741750

- NgCH.EastealS.TanS.SchweitzerI.HoBK.AzizS.Serotonin transporter polymorphisms and clinical response to sertraline across ethnicitiesProgr Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry.200630953957

- RauschJL.HobbyHM.ShendarkarN.JohnsonME.LiJ.Fluvoxamine treatment of mixed anxiety and depression: evidence for serotonergically mediated anxiolysisClin Psychopharmacoi.200121139142

- SmeraldiE.ZanardiR.BenedettiF.Di BellaD.PerezJ.CatalaneM.Polymorphism within the promoter of the serotonin transporter gene and antidepressant efficacy of fluvoxamineMol Psychiatry.199835085119857976

- YuYW.TsaiSJ.ChenTJ.LinCH.HongCJ.Association study of the serotonin transporter promoter polymorphism and symptomatology and antidepressant response in major depressive disordersMol Psychiatry.200271115111912476327

- ZanardiR.BenedettiF.Di BellaD.CatalanoM.SmeraldiE.Efficacy of paroxetine in depression is influenced by a functional polymorphism within the promoter of the serotonin transporter geneJ Clin Psychopharmacoi.200020105107

- ZanardiR.SerrettiA.RossiniD.etal.Factors affecting fluvoxamine antidepressant activity: influence of pindolol and 5-HTTLPR in delusional and nondelusional depressionBiol Psychiatry.20015032333011543734

- Dmitrzak-WeglarzM.Rajewska-RagerA.GattnerK.et alAssociation studies of 5HT2Â and 5HTTLPR polymorphisms and drug response in depression patientsEur Neuropsychopharmacol.200717(s4)S238

- KimD.K.LimS.W.LeeS.et alSerotonin transporter gene polymorphism and antidepressant responseNeuroreport.20001121521910683861

- KraftJB.SlagerSL.McGrathPJ.HamiltonSP.Sequence analysis of the serotonin transporter and associations with antidepressant responseBiol Psychiatry.20055837438115993855

- MinovC.BaghaiTC.SchuleC.et alSerotonin-2A-receptor and -transporter polymorphisms: lack of association in patients with major depressionNeurosci Lett.200130311912211311507

- YoshidaK.ItoK.SatoK.et alInfluence of the serotonin transporter gene-linked polymorphic region on the antidepressant response to fluvoxamine in Japanese depressed patientsProgr Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry.200226383386

- SerrettiA.CusinC.RauschJL.BondyB.SmeraldiE.Pooling pharmacogenetic studies on the serotonin transporter: a mega-analysisPsychiatry Res.2006145616517069894

- SerrettiA.KatoM.De RonchiD.KinoshitaT.Meta-analysis of serotonin transporter gene promoter polymorphism (5-HTTLPR) association with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor efficacy in depressed patientsMol Psychiatry.20071224725717146470

- SmltsKM.SmitsLJ.SchoutenJS.StelrnaFF.NelemansP.PrinsMH.Influence of SERTPR and STin2 in the serotonin transporter gene on the effect of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in depression: a systematic reviewMol Psychiatry,2004943344115037864

- KraftJB.PetersEJ.SlagerSL.et alAnalysis of association between the serotonin transporter and antidepressant response in a large clinical sampleBiol Psychiatry.20076173474217123473

- HuXZ.RushAJ.CharneyD.et alAssociation between a functional serotonin transporter promoter polymorphism and citalopram treatment in adult outpatients with major depressionArch Gen Psychiatry.20076478379217606812

- ChoiMJ.KangRH.HamBJ.JeongHY.LeeMS.Serotonin receptor 2A gene polymorphism (-1438A/G) and short-term treatment response to citalopramNeuropsychobiology.20055215516216127283

- SatoK.YoshidaK.TakahashiH.et alAssociation between -1438G/A promoter polymorphism in the 5-HT(2A) receptor gene and fluvoxamine response in Japanese patients with major depressive disorderNeuropsychobiology.20024613614012422060

- McMahonFJ.BuervenichS.CharneyD.et alVariation in the gene encoding the serotonin 2Â receptor is associated with outcome of antidepressant treatmentAm J Hum Genet.20067880481416642436

- PerlisRH.MoorjaniP.EagernessJ.et alPharmacogenetic analysis of genes implicated in rodent models of antidepressant response: association of TREK1 and treatment resistance in the STAR(*)D StudyNeuropsychopharmacol.20083328102819

- PaddockS.LajeG.CharneyD.et alAssociation of GRIK4 with Outcome of Antidepressant Treatment in the STAR*D CohortAm J Psychiatry.20071641181118817671280

- LekmanM.LajeG.CharneyD.et alThe FKBP5-gene in depression and treatment response-an association study in the sequenced treatment alternatives to relieve depression (STAR*D) cohortBiol Psychiatry.2008631103111018191112

- TsapakisEM.CheckleyS.KerwinRW.AitchisonKJ.Association between the serotonin transporter linked polymorphic region gene (5HTTLPR) and response to tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs)Eur Neuropsychopharmacol.200313S250

- ChoiTK.KooMS.LeeSH.SeokJH.KirnSJ.Serotonin transporter gene polymorphism associated with venlafaxine treatment responseEur Neuropsychopharmacol.200717(s4)S228

- KangRH.WongML.ChoiMJ.PaikJW.LeeMS.Association study of the serotonin transporter promoter polymorphism and mirtazapine antidepressant response in major depressive disorderProgr Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry.20073113171321

- MullerDJ.SchulzeTG.MacciardiF.et alMoclobemide response in depressed patients: association study with a functional polymorphism in the monoamine oxidase A promoterPharmacopsychiatry,20023515715812163988

- JoycePR.MulderRT.LutySE.et alAge-dependent antidepressant pharmacogenomics: polymorphisms of the serotonin transporter and G protein beta3 subunit as predictors of response to fluoxetine and nortriptylineInt J Neuropsychopharmacol.2003633934614604448

- SzegediA.RujescuD.TadicA.et alThe catechol-O-methyltransferase Val108/158Met polymorphism affects short-term treatment response to mirtazapine, but not to paroxetine in major depressionPharmacogenomics J.20055495315520843

- MaybergHS.SilvaJA.BrannanSK.et alThe functional neuroanatomy of the placebo effectAm J Psychiatry.200215972873711986125

- MaybergHS.BrannanSK.TekellJL.etal.Regional metabolic effects of fluoxetine in major depression: serial changes and relationship to clinical responseBiol Psychiatry.20004883084311063978

- losifescuDV.BobNR.NierenbergAA.JensenJE.FavaM.RenshawPFBrain bioenergetics and response to triiodothyronine augmentation in major depressive disorderBiol Psychiatry.2008631127113418206856

- LittleJT.KetterTA.KimbrellTA.et alBupropion and venlafaxine responders differ in pretreatment regional cerebral metabolism in unipolar depressionBiol Psychiatry.20055722022815691522

- HunterAM.CookIA.LeuchterAF.The promise of the quantitative electroencephalogram as a predictor of antidepressant treatment outcomes in major depressive disorderPsychiatr Clin N Am.200730105124

- LeuchterAF.CookIA.LufkinRB.et alCordance: a new method for assessment of cerebral perfusion and metabolism using quantitative electroencephalographyNeurolmage.19941208219

- BaresM.BrunovskyM.KopecekM.et alChanges in QEEG prefrontal cordance as a predictor of response to antidepressants in patients with treatment resistant depressive disorder: a pilot studyJ Psych Res.200741319325

- CookIA.LeuchterAF.MorganM.et alEarly changes in prefrontal activity characterize clinical responders to antidepressantsNeuropsychopharmacol.200227120131

- CookIA.LeuchterAF.MorganML.StubbemanW.SlegmanB.AbramsM.Changes in prefrontal activity characterize clinical response in SSRI nonresponders: a pilot studyJ Psych Res.200539461466

- LeuchterAF.CookIA.WitteEA.MorganM.AbramsM.Changes in brain function of depressed subjects during treatment with placeboAm J Psychiatry.200215912212911772700

- HunterAM.LeuchterAF.MorganML.CookIA.Changes in brain function (quantitative EEG cordance) during placebo lead-in and treatment outcomes in clinical trials for major depressionAm J Psychiatry.20061631426143216877657

- HegerlU.JuckelG.Intensity dependence of auditory evoked potentials as an indicator of central serotonergic neurotransmission: a new hypothesisBiol Psychiatry.1993331731878383545

- GalllnatJ.BottlenderR.JuckelG.et alThe loudness dependency of the auditory evoked N1/P2-component as a predictor of the acute SSRI response in depressionPsychopharmacology (Berl).200014840441110928314

- LinkaT.MillierBW.BenderS.SartoryG.The intensity dependence of the auditory evoked N1 component as a predictor of response to Citalopram treatment in patients with major depressionNeurosci Lett.200436737537815337269

- MulertC.JuckelG.AugustinH.HegerlU.Comparison between the analysis of the loudness dependency of the auditory N1/P2 component with LORETA and dipole source analysis in the prediction of treatment response to the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor citalopram in major depressionClin Neurophysiol.20021131566157212350432

- MulertC.JuckelG.BrunnmeierM.et alPrediction of treatment response in major depression: integration of conceptsJ Affect Disord.20079821522516996140

- PaigeSR.FitzpatrickDF.KlineJP.BaloghSE.HendricksSE.Event-related potential amplitude/intensity slopes predict response to antidepressantsNeuropsychobiology.1994301972017862269

- JuckelG.PogarellO.AugustinH.et alDifferential prediction of first clinical response to serotonergic and noradrenergic antidepressants using the loudness dependence of auditory evoked potentials in patients with major depressive disorderJ Clin Psychiatry.2007681206121217854244

- BruderGE.StewartJW.VoglmaierMM.et alCerebral laterality and depression: relations of perceptual asymmetry to outcome of treatment with tricyclic antidepressantsNeuropsychopharmacology.199031102306330

- BruderGE.OttoMW.McGrathPJ.et alDichotic listening before and after fluoxetine treatment for major depression: relations of laterality to therapeutic responseNeuropsychopharmacology,1996151711798840353

- BruderGE.StewartJW.McGrathPJ.DeliyannidesD.QuitkinFM.Dichotic listening tests of functional brain asymmetry predict response to fluoxetine in depressed women and men.Neuropsychopharmacology,2004291752176115238992

- BraderGE.StewartJW.SchallerJD.McGrathPJ.Predicting therapeutic response to secondary treatment with bupropion: Dichotic listening tests of functional brain asymmetry.Psychiatry Res.200715313714317651813