Abstract

Anxiety disorders, including panic disorder with or without agoraphobia, generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, specific phobias, and separation anxiety disorder, are the most prevalent mental disorders and are associated with immense health care costs and a high burden of disease. According to large population-based surveys, up to 33.7% of the population are affected by an anxiety disorder during their lifetime. Substantial underrecognition and undertreatment of these disorders have been demonstrated. There is no evidence that the prevalence rates of anxiety disorders have changed in the past years. In cross-cultural comparisons, prevalence rates are highly variable. It is more likely that this heterogeneity is due to differences in methodology than to cultural influences. Anxiety disorders follow a chronic course; however, there is a natural decrease in prevalence rates with older age. Anxiety disorders are highly comorbid with other anxiety disorders and other mental disorders.

Los trastornos de ansiedad, que incluyen el trastorno de pánico con o sin agorafobia, el trastorno de ansiedad generalizada, el trastorno de ansiedad social, las fobias específicas y el trastorno de ansiedad por separación son los trastornos mentales más prevalentes y están asociados con inmensos costos de atención de salud y una alta carga de enfermedad. De acuerdo con investigaciones basadas en grandes poblaciones, hasta un 33,7% de la población presenta un trastorno de ansiedad durante su vida. Se ha demostrado que el subdiagnóstico y el subtratamiento de estos trastornos es significativo. No existe evidencia acerca del cambío en las frecuencias de prevalencia de los trastornos de ansiedad en los últimos años. En comparaciones interculturales las frecuencias de prevalencía son altamente variables. Es más probable que esta heterogeneidad se deba a diferencias en la metodología más que a influencias culturales. Los trastornos de ansiedad siguen un curso crónico; sin embargo, hay una disminución natural en las frecuencias de prevalencia a mayor edad. Los trastornos de ansiedad son altamente comórbidos con otros trastornos ansiosos y otros trastornos mentales.

Les troubles anxieux, dont le trouble panique avec ou sans agoraphobie, le trouble anxieux généralisé, l'anxiété sociale, les phobies spécifiques et l'anxiété de séparation, sont les troubles mentaux les plus prévalents avec des coûts immenses en termes de santé et une charge élevée. D'après de grandes études basées sur la population, jusqu'à 33,7 % de la population souffre d'un trouble anxieux au cours de la vie. Ces pathologies sont manifestement sous-diagnostiquées et sous-traitées. Leur prévalence n'a pas montré de modification ces dernières années et est très variable dans les comparaisons interculturelles. Cette hétérogénéité est probablement plus due à des biais méthodologiques qu'à des influences culturelles. L'évolution des troubles anxieux est chronique mais leur prévalence diminue cependant naturellement avec l'âge. Leur comorbidité avec les autres troubles anxieux et les autres maladies mentales est très élevée.

Introduction

In 1621, Robert Burton described the symptoms of anxiety attacks in socially anxious people in his book The Anatomy of Melancholy Citation1: “Many lamentable effects this fear causeth in man, as to be red, pale, tremble, sweat; it makes sudden cold and heat come over all the body, palpitation of the heart, syncope, etc. It amazeth many men that are to speak or show themselves in public.” In the same book, Burton cited Hippocrates' writing on one of his patients, who apparently suffered from what we would call “social anxiety disorder” today: “He dare not come into company for fear he should be misused, disgraced, overshoot himself in gestures or speeches, or be sick; he thinks every man observeth him.”

Pathological anxiety, such as social phobia, has always existed in humans. Is there a reason to believe that anything has changed in the 21st century? There is a widespread opinion that anxiety is a characteristic feature of our modern times, and that the prevalence of anxiety disorders has increased due to certain political, societal, economical, or environmental changes.

Among all mental diseases, the anxiety disorders, including panic disorder with or without agoraphobia, generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), social anxiety disorder (SAD), specific phobias, and separation anxiety disorder, are the most frequent.Citation2 Because patients with anxiety disorders are mostly treated as outpatients, they probably receive less attention from clinical psychiatrists than patients with other disorders that require inpatient treatment but are less frequent, such as schizophrenia or bipolar affective disorders.

Methodology of epidemiologic studies

Epidemiologic studies in psychiatry may help in assessing the importance of a certain disorder in order to develop treatment strategies and in planning special health prevention programs. They may provide useful information on the use of health services and the economic impact of psychiatric disorders on the health care system. Epidemiologic research may also help us to better understand the etiology of mental disorders.

Prevalence rates

In epidemiologic studies, different kinds of prevalence rates are assessed. The lifetime prevalence is the proportion of individuals who have suffered from a certain disorder once in their life. The annual prevalence is the percentage of probands who experienced the disorder in the 12 months before the survey. Disorders of longer duration are likely to be overrepresented in annual prevalence rates compared with those of short duration. The more chronic a disease, the more similarities between lifetime and 12-month prevalence rates should be found. The point prevalence is the prevalence of a disorder on a certain effective day.

Representativeness of epidemiological studies

Community surveys

One relatively simple way to find out how many people suffer from certain psychiatric disorders would be to review the charts of all patients who attend a large mental health service. However, by simply counting the individuals suffering from major depression or panic disorder who consult a psychiatrist in private practice or a mental hospital, one would obtain prevalence rates that are significantly biased, as they may be influenced by various factors such as specialty of the physician or the institution. Moreover, the representativeness of such rates would be limited because patients with certain psychiatric disorders, such as patients with somatization disorder, tend to have high medical care utilization, while others, such as patients with specific phobias, may only rarely seek psychiatric help. Due to the stigma associated with mental disorders, many affected individuals are reluctant to contact mental health professionals. Finally, many patients in some countries can simply not afford to see a physician, which would lead to an underestimation of the prevalence of certain disorders in this population.

The only way to obtain reliable prevalence rates is a so-called “doorknock” survey, in which representative samples are collected by using methods known from population polls. From a listing of all residential addresses, systematic samples are selected from different regions, including urban and rural sites. Then, interviewers contact these households and interview the selected member using a structured questionnaire. To obtain a complete overview, representative surveys should also include patients currently hospitalized or in long-term facilities. However, not all published studies have incorporated the inpatient population, perhaps due to the high administrative burden associated with such surveys.

The sample sizes of epidemiological surveys should be very large, in order to obtain reliable and generalizable results not only for frequent disorders but also for rare illnesses. In particular, subgroup analyses that compare prevalence rates with regard to gender, age, ethnicity, and other factors require large sample sizes.

Community surveys are associated with certain strengths and weaknesses. They are representative, not confounded by the factor of treatment-seeking, and provide large sample sizes, which allow statistical analyses with sufficient power. However, it is a disadvantage that in community surveys diagnoses are not made by experienced psychiatrists or psychologists. When large samples are investigated in population surveys, it would not be feasible to employ psychiatrists or psychologists as interviewers, due to the higher expenditures and the difficulty of recruiting a sufficient number of trained specialists for the assessment. Therefore, these studies are usually conducted by professional interviewers without medical backgrounds, who go through a specific training program for psychiatric interviews. The fact that the prevalence rates for some mental disorders obtained in community services seem to be grossly exaggerated has often been criticized. For example, according to the NCS study,Citation3 every third woman suffers from an anxiety disorder once in her life. Even for well-trained lay interviewers, it may be difficult to reliably differentiate between subthreshold cases and clinically significant cases on the basis of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (DSM) and International Classification of Diseases (ICD) classification systems. Some of the DSM and ICD criteria were decided by committees rather than being empirically derived from field studies, and do not provide clear cutoff scores to identify clinical cases. For anxiety disorders, in particular, it is difficult to draw a clear line between pathological and well-founded fear. Anxiety belongs to our daily life, and individuals without fear would not survive for long. For example, even for qualified psychiatrists it may be a challenge to differentiate between mild forms of social anxiety disorder and “normal” shyness or modesty. Likewise, many mothers would say “yes” to the question as to whether they worry constantly that some accident could happen to their children, but an interview could feasibly lead to a diagnosis of GAD in a healthy mother. A psychiatrist who is seeing patients with GAD every day would probably take other signs and symptoms into account when differentiating between normal worries and pathological fear.

Some representative surveys have been conducted in recent years, using complex sampling methods, well-defined diagnostic criteria, elaborate questionnaires, and sophisticated statistical methods. In Table I, the largest studies are shown: the Epidemiologic Catchment Area Program (ECA), the National Comorbidity Survey-Replication (NCS), and the European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD)

Table I Large epidemiological community surveys.

Surveys in clinical settings

However, studies conducted in psychiatric outpatient services or in primary care settings may also yield valuable information. If interviews are conducted by psychiatrists (eg, Wittchen et alCitation4) or the study uses a general psychiatric outpatient sample (eg, Lepine et alCitation5), the clinical cases will probably be identified more reliably. A worldwide survey conducted by the World Health Organization (WHO) explored the frequency of mental problems in primary care or general health settings.Citation6 In this study, persons who were consulting health care services were screened for psychological problems and psychiatric disorders, regardless of their reason for attending that service, ie, persons consulting the doctor for a nonpsychiatric disorder, such as diabetes or hypertension, were also included. These studies are not appropriate for obtaining representative prevalence rates for the reasons given above. However, they may yield valuable information on the use of health services and the social and financial burden of psychiatric disorders.

In statistical investigations conducted in hospitalized psychiatric patients, mental disorders like depression, schizophrenia, or personality disorders are usually overrepresented, because certain features of these disorders require inpatient treatment, including suicidality, hostility, or reduced social integration. In these surveys, patients with anxiety disorders are generally underrepresented, as anxiety disorders rarely require inpatient treatment.

Diagnosis and interview technique

In order to obtain reliable diagnoses, interviews are usually based on the current version of the standard diagnostic tools DSM Citation7 or ICD Citation8 In order to structure the diagnostic process and to obtain objective results, special interview manuals have been developed. These include:

The Structured Interview for DSM (SCID),Citation9,Citation10 a semistructured interview for major DSM Axis I diagnoses, which is administered by clinicians

The Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS),Citation11 which made it possible for the first time for trained lay interviewers to carry out assessments of clinically significant mental disorders. Before its development, the comparability of cross-national comparisons was hampered by the the absence of common standards and operational procedures for diagnostic interviews

The Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) 3.0 for DSM,Citation12 which combines questions from the DIS with Present State Examination questions and is administered by lay interviewers

The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I 6.0), Citation13 a structured diagnostic tool for DSM and ICD, which was designed to be a short but accurate psychiatric interview for epidemiologic studies.

Prevalence rates

In Table II, the prevalence rates for the three large community surveys are presented. Additionally, Wittchen and JacobiCitation14 have summarized the results of 27 European studies (including the ESEMeD study). Twenty-four of these were national studies and three were cross-national studies. According to these surveys, specific phobias and SAD are the most common disorders.

Table II Prevalence rates of anxiety disorders in epidemiological surveys. ECA, Epidemiologic Catchment Area Program; NCS-R, National Comorbidity Survey-Replication; ESEMeD, European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders

Even the representative population surveys show substantial discrepancies in prevalence rates. This may be attributed to various factors, including methodological differences that could distort the actual prevalence rates, for example:

Variation in the use of the diagnostic criteria (eg, different versions of the DSM)

Variation in the use of the diagnostic interview tools

Methods of data collection

Type of interviewer

Interviewer instructionsCitation15

Language differences or translating problems

Cultural styles in conveying psychiatric symptoms

Target population of the sample investigated (eg, differences in age range, inclusion of hospitalized patients etc)Citation2

Standardization of prevalence rates to the census population of each site instead of to an identical population.Citation16

However, actual differences between the investigated populations may also exist, which may be due to:

Biological differences across races and ethnic groups

Culturally determined psychosocial differences (eg, different roles of women in society)

Traumatic stressors that influence whole nations or ethnic groups (eg, war, poverty, natural disasters, or suppression of minorities).

Separation anxiety disorder

Before the development of DSM-5,Citation7 separation anxiety disorder could only be diagnosed in children or adolescents. Therefore, adult separation anxiety disorder did not appear in the older epidemiological studies. According to a newer survey, the lifetime prevalence rate for adolescents aged 13 to 17 was 7.7%, while it was 6.6% in adults aged 18 to 64.Citation3

Sex differences

In Table III, the female:male ratios for the prevalence rates of anxiety disorders are shown. Although these rates are heterogenous, it is a consistent finding that the prevalence of anxiety disorders in women is approximately twice as high as in men. Psychosocial contributors (eg, childhood sexual abuse and chronic stressors), but also genetic and neurobiological factors, have been discussed as possible causes for the higher prevalence in women.Citation17

Table III Female-to-male ratio of prevalence rates for anxiety disorders (calculated from the prevalence rates reported in major epidemiological surveys). ECA, Epidemiologic Catchment Area Program; NCS-R, National Comorbidity Survey-Replication; ESEMeD, European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders

Age of onset and course

Prospective studies suggest that anxiety disorders are chronic, ie, patients may suffer from their disorder for years or decades. However, this does not mean that an anxiety disorder lasts permanently for the rest of the patient's life. Anxiety disorders start in childhood, adolescence, or early adulthood until they reach a peak in middle age, then tending to decrease again with older age.

In the NCS-R, mental disorders were studied in a large sample of 10 148 adolescents aged 13 to 17 years.Citation18 As in adults, anxiety disorders are the most common class of mental disorders, with a 12-month prevalence rate of 24.9%. Specific phobias and social anxiety disorder were the most common disorders. Compared with adults aged 18 to 64, the lifetime prevalence was less for panic disorder, GAD, and SAD, whereas specific phobias, separation anxiety disorder, and agoraphobia without a history of panic attacks were more common in adolescents aged 13 to 17 years.Citation3

The median age of onset for anxiety disorders is 11 years.Citation19 Specific phobias and separation anxiety disorder start earliest, with a median age of onset of 7 years, followed by SAD (13), agoraphobia without panic attacks (20), and panic disorder (24). GAD has the latest median age at onset (31 years). According to a German epidemiological study,Citation20 the 12-month prevalence rates for SAD, GAD, and specific phobia were highest in the 18- to 34-year age group, while they were highest for panic disorder in the 35- to 49-year group. In the 50- to 64-year age group, prevalence rates decreased. They were and were lowest in the elderly (65 to 79 years). That means that even without treatment, anxiety disorders do not last until old age in most cases.

Health care utilization

Anxiety disorders can be treated successfully with medication and psychological therapies, eg, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT).Citation21,Citation22 According to newer meta-analytical data, improvement effect sizes obtained with psychopharmacological drugs are higher than those achieved with CBT.Citation23 However, a substantial underrecognition and undertreatment of anxiety disorders and depression has been reported. According to a WHO study, only approximately half of the cases of anxiety disorders have been recognized, and only one third of the affected patients were offered drug treatment.Citation24 In the ESEMeD study, only one fifth (20.6%) of participants with an anxiety disorder sought help from health care services. Of those who contacted health services, 23.2% received no treatment of all. Of the others, 30.8% received only drug treatment, 19.6% received only psychological treatment, and 26.5 were treated with both medication and psychotherapy.Citation25

For many patients it may last years until they are referred to a specialist. According to a survey among psychiatrists who were experienced in the treatment of anxiety disorders, 45% of patients suffered from symptoms of GAD for 2 years or more before they were correctly diagnosed with the disorder.Citation26

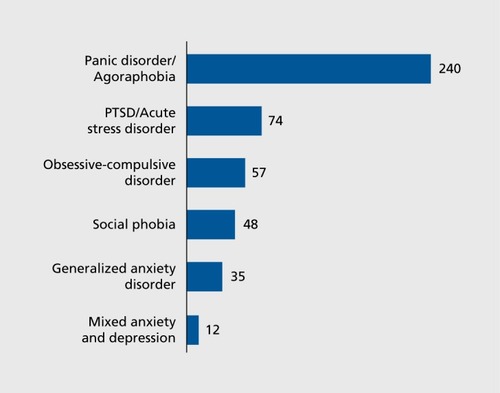

The different anxiety disorders show varying patterns in health care utilization, explaining why prevalence rates found in representative epidemiologic surveys differ from statistical studies in clinical settings. For example, 54.4% of patients with panic disorder, but only 27.3% of patients with phobias, contacted health care services.Citation27 Patients with panic disorder often assume that they have a medical rather than a psychiatric condition, and tend to have themselves re-examined repeatedly in internal medical or emergency wards. In contrast, patients with social phobia tend to hide their problem. As shyness and shame are typical features of social anxiety, it is not surprising that these patients are hesitant to see a physician and to talk about their problem. Patients with specific phobias can mostly cope with their problem. They can avoid having contact with the objects or situations they fear, such as dogs, heights, or insects, without major restrictions in quality of life. Thus, these persons very rarely seek professional help. These considerations may explain why psychiatrists or special anxiety disorders units mostly see patients with panic disorder. For example, in our special anxiety disorders unit at the University of Gottingen, Germany, the number of patients seeking help differed substantially from the actual prevalence rates in the population ( ). Panic disorder with or without agoraphobia was by far the most frequent reason to consult the unit. SAD and GAD patients were underrepresented in this clinical setting, and no patient sought help for a specific phobia.Citation28

Burden of illness

It was estimated that in 2004, anxiety disorders cost in excess of 41 billion Euros in the European Union.Citation29 Results from a German survey showed that the excess costs associated with anxiety disorders ranged from €500 to €1600 per case in 2004.Citation29 The work loss days for some anxiety disorders are higher than for common somatic disorders such as diabetes.Citation30 In the European Union, anxiety disorders are responsible for a large proportion of overall burden of disease. Disability-adjusted life years lost (DALY) is a global measure of disease burden, expressed as the number of years lost due to illness, disability, or early death. The DALY which can be attributed to panic disorder were estimated at 383 783,Citation14 This is less than the DALY caused by the most important contributors to burden of disease — depression, dementia, and alcohol abuse, but more than the DALY for Parkinson's disease, epilepsy, or multiple sclerosis.

Is the prevalence of anxiety disorders increasing?

It is a widespread opinion in the media that “each year more and more people are suffering from anxiety disorders,” suggesting there has been a relative increase in anxiety disorders over the past 10, 50, or 100 years. However, it is difficult to find reliable evidence for a change in prevalence rates for anxiety disorders. Epidemiologic data obtained before the introduction of psychiatric classification systems such as the DSM-III Citation31 are too imprecise to be comparable with modern studies. In 1980, the anxiety disorders were reclassified, and panic disorder was incorporated as a new diagnostic entity.

To verify the hypothesis that there is an increase or decrease in certain psychiatric disorders, one would have to repeat large epidemiologic surveys after a certain time span in the same population using the same methodological setting. There is one epidemiological program that can provide comparable data for two timepoints: the National Comorbidity Survey (NCS) was performed in the years 1990 to 1992Citation2 and replicated 11 years later (NCS-R) in the years 2001 to 2003.Citation32 For this relatively short time span, no significant increase of prevalence rates could be demonstrated for mental disorders in general.Citation2,Citation33 However, the rate of treatment-seeking individuals increased, which may the reason for the general impression that these disorders are more frequent. Likewise, a comparison of data from the European Union did not show a significant change in prevalence rates for anxiety disorders between 2005 and 2011.Citation34

There is a reason that it is unlikely that the prevalence rates have changed substantially over the years. For all anxiety disorders, a heritability of approximately 30% to 50% has been reportedCitation35 — and heritable disorders would not change their clinical picture substantially over decades or centuries.

Cross-cultural differences

When it is found that the prevalence rates of the anxiety disorders are more or less the same in many different countries, despite different cultural and social environments, it seems less probable that these disorders can be attributed mainly to cultural or psychosocial causes. If this is the case, genetic and neurobiological determinants that are distributed statistically among all people, regardless of their sociocultural surroundings, must also be seen as a relevant etiological factor. When, however, the distribution of anxiety disorders is different across various cultures and time periods, this would support environmental influences in the etiology of these disorders.

In a review of 27 epidemiological studies, Wittchen and Jacobi compared the prevalence rates in 16 European countries. The findings were highly heterogenous. For example, 12-month prevalence rates were found to be between 0.6 and 7.9% for SAD and between 0.2 and 4.3 for GAD in the different countries. Likewise, other articles comparing the prevalence of panic disorder across different countries and cultures (included Canada, Germany, Italy, Korea, Lebanon, New Zealand, Puerto Rico, the USA, and Taiwan) found high variability in prevalence rates.Citation36,Citation37 It would be premature to attribute these differences to actual cultural influences — as the same high heterogeneity in prevalence rates was found when different samples from the same countries were compared with each other. It is more likely that differences in methodology account for these differences.

Comorbidity

Most studies show a high overlap among the anxiety disorders and between the anxiety disorders and other mental disorders, respectively. In the NCS-R,Citation32 the highest tetrachoric correlations among the anxiety disorders were found between SAD and agoraphobia (r=0.68), between panic disorder and agoraphobia (0.64), and between specific phobia and agoraphobia (0.57). Regarding the overlap with other mental disorders, the correlation between GAD with major depression (r=0.62) was particularly high. Also, high correlations of 0.55 each were found between dysthymia and GAD or SAD, respectively.

In clinical settings, the relative proportion of comorbid cases is usually higher than that found in representative population surveys, because individuals with two concomitant disorders, suffering from a high overall burden, are more likely to seek treatment than individuals with only one disorder (Berkson's paradox).

Conclusions and future perspectives

Anxiety disorders are the most prevalent psychiatric disorders. According to epidemiological surveys, one third of the population is affected by an anxiety disorder during their lifetime. They are more common in women. During midlife, their prevalence is highest. These disorders are associated with a considerable degree of impairment, high health-care utilization and an enormous economic burden for society. Although effective psychological and pharmacological treatments exist for anxiety disorders, many affected individuals do not contact health services for treatment, and of those who utilize these services, a high percentage is not diagnosed correctly or not offered state-of-the-art treatment. There is no evidence that the prevalence rates have changed in the past years. Differences in prevalence rates found in different countries and cultures may be due to differences in methodology rather than to culture-specific factors. High comorbidity is found among the anxiety disorders and between the anxiety disorders and other mental disorders, respectively. Epidemiologic studies may help in planning treatment and prevention programs, and they may also help us to better understand the etiology of these disorders.

REFERENCES

- BurtonR.The Anatomy of Melancholy. London, UK:1621

- KesslerRC.McGonagleKA.ZhaoS.et alLifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Results from the National Comorbidity Survey.Arch Gen Psychiatry19945118198279933

- KesslerRC.PetukhovaM.SampsonNA.ZaslavskyAM.WittchenHU.Twelve-month and lifetime prevalence and lifetime morbid risk of anxiety and mood disorders in the United States.Int J Methods Psychiatr Res.201221316918422865617

- WittchenHU.EssauCA.von ZerssenD.KriegJC.ZaudigM.Lifetime and six-month prevalence of mental disorders in the Munich Follow-Up Study.Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci.199224142472581576182

- LepineJP.ParienteP.BoulengerJP.et alAnxiety disorders in a French general psychiatric outpatient sample. Comparison between DSM-III and DSM-IIIR criteria.Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol.19892463013082512648

- SartoriusN.UstunTB.Costa e SilvaJA.et alAn international study of psychological problems in primary care. Preliminary report from the World Health Organization Collaborative Project on 'Psychological Problems in General Health Care'.Arch Gen Psychiatry199350108198248215805

- American Psychiatric Association.Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association;2013

- World Health Organization.The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioral Disorders. Clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization;1992

- SpitzerRL.WilliamsJB.GibbonM.FirstMB.The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID). I: History, rationale, and description.Arch Gen Psychiatry.19924986246291637252

- WilliamsJB.GibbonM.FirstMB.et alThe Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID). II. Multisite test-retest reliability.Arch Gen Psychiatry19924986306361637253

- RobinsLN.HelzerJE.CroughanJ.RatcliffKS.National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule. Its history, characteristics, and validity.Arch Gen Psychiatry.19813843813896260053

- KesslerRC.UstunTB.The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI).Int J Methods Psychiatr Res.20041329312115297906

- SheehanDV.LecrubierY.SheehanKH.et alThe Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N. I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10.J Clin Psychiatry199859suppl 202233;quiz 34-579881538

- WittchenHU.JacobiF.Size and burden of mental disorders in Europe — a critical review and appraisal of 27 studies.Eur Neuropsychopharmacol.200515435737615961293

- RobinsLN.HelzerJE.WeissmanMM.et alLifetime preva lence of specific psychiatric disorders in three sites.Arch Gen Psychiatry.198441109499586332590

- BlandRC.OrnH.NewmanSC.Lifetime prevalence of psychiatric disorders in Edmonton.Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl.198833824323165592

- BandelowB.DomschkeK.Panic Disorder. In: Stein D, Vythilingum B, eds.Anxiety Disorders and Gender. Cham, Switzerland: Springer;2015

- KesslerRC.AvenevoliS.CostelloEJ.et alPrevalence, persistence, and sociodemographic correlates of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement.Arch Gen Psychiatry201269437238022147808

- KesslerRC.BerglundP.DernierO.JinR.MerikangasKR.WaltersEE.Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication.Arch Gen Psychiatry2005626 59360215939837

- JacobiF.HoflerM.StrehleJ.et al[Mental disorders in the general population: Study on the health of adults in Germany and the additional module mental health (DEGS1-MH)].Nervenarzt.2014851778724441882

- BandelowB.ZoharJ.HollanderE.et alWorld Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of anxiety, obsessive-compulsive and post-traumatic stress disorders - first revision.World J Biol Psychiatry.20089424831218949648

- BaldwinDS.AndersonIM.NuttDJ.et alEvidence-based pharmacological treatment of anxiety disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder: a revision of the 2005 guidelines from the British Association for Psychopharmacology.J Psychopharmacol.201428540343924713617

- BandelowB.ReittM.RoverC.MichaelisS.GorlichY.WedekindD.Efficacy of treatments for anxiety disorders: a meta-analysis.Int Clin Psychopharmacol.201530418319225932596

- SartoriusN.UstunTB.LecrubierY.WittchenHU.Depression comorbid with anxiety: results from the WHO study on psychological disorders in primary health care.Br J Psychiatry199630303843

- AlonsoJ.LepineJP.CommitteeESMS.Overview of key data from the European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD).J Clin Psychiatry200768suppl 23917288501

- BaldwinDS.AllgulanderC.BandelowB.FerreF.PallantiS.An international survey of reported prescribing practice in the treatment of patients with generalised anxiety disorder.World J Biol Psychiatry201213751051622059936

- RegierDA.NarrowWE.RaeDS.ManderscheidRW.LockeBZ.GoodwinFK.The de facto US mental and addictive disorders service system. Epidemiologic catchment area prospective 1-year prevalence rates of disorders and services.Arch Gen Psychiatry199350285948427558

- BandelowB.Epidemiology of depression and anxiety. In: Kasper S, den Boer JA, Sitsen AJM, eds.Handbook on Depression and Anxiety. New York, NY: M. Dekker;2003x4968

- Andlin-SobockiP.WittchenHU.Cost of anxiety disorders in Europe.Eur J Neurol.200512suppl 1394415877777

- AlonsoJ.AngermeyerMC.BernertS.et alUse of mental health services in Europe: results from the European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD) project.Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl.2004 420475415128387

- American Psychiatric Association.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 3rd ed. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association;1980

- KesslerRC.ChiuWT.DernierO.MerikangasKR.WaltersEE.Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication.Arch Gen Psychiatry200562661762715939839

- KesslerRC.DemlerO.FrankRG.et alPrevalence and treatment of mental disorders, 1990 to 2003.N Engl J Med.2005352242515252315958807

- WittchenHU.JacobiF.RehmJ.et alThe size and burden of mental disorders and other disorders of the brain in Europe 2010.Eur Neuropsychopharmacol.201121965567921896369

- Shimada-SugimotoM.OtowaT.HettemaJM.Genetics of anxiety disorders: Genetic epidemiological and molecular studies in humans.Psychiatry Clin Neurosci.201569738840125762210

- AmeringM.KatschnigH.Panic attacks and panic disorder in crosscultural-perspective.Psychiatr Annals.1990209511516

- WeissmanMM.BlandRC.CaninoGJ.et alThe cross-national epidemiology of panic disorder.Arch Gen Psychiatry19975443053099107146

- FichterMM.NarrowWE.RoperMT.et alPrevalence of mental illness in Germany and the United States. Comparison of the Upper Bavarian Study and the Epidemiologic Catchment Area Program.J Nerv Ment Dis.1996184105986068917156

- BourdonKH.RaeDS.LockeBZ.NarrowWE.RegierDA.Estimating the prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adults from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area Survey.Public Health Rep.199210766636681454978

- RegierDA.NarrowWE.RaeDS.The epidemiology of anxiety disorders: the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) experience.J Psychiatr Res.199024suppl 23142280373

- AlonsoJ.AngermeyerMC.BernertS.et alPrevalence of mental disorders in Europe: results from the European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD) project.Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl.2004 420212715128384