Abstract

Purpose

The aim of the study was to explore self-perceived change in work ability among persons attending occupational rehabilitation programs.

Method

We interviewed 17 persons 6 months after they had attended an inpatient occupational rehabilitation program in Norway. At the time of the interview, five participants worked full time, six worked reduced hours, and six were not working. Data were analyzed by use of the systematic text condensation method.

Results

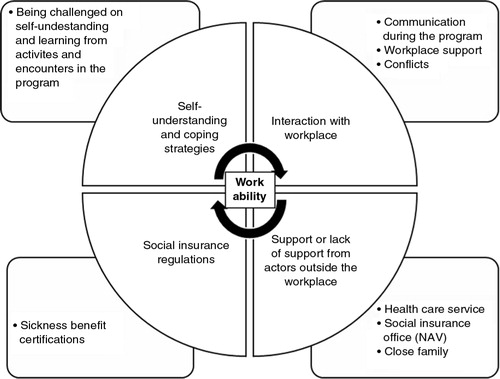

Self-perceived change in work ability during and after the rehabilitation program was influenced by the development of the participants’ self-understanding and coping strategies, interaction with the workplace, support from actors outside the workplace, and social insurance regulations. The participants increased their self-understanding and coping strategies after being challenged on self-understanding and learning through counseling from rehabilitation professionals, through interaction with fellow participants, or through experiences from physical activities. After the program, the participants’ interaction with their surroundings influenced their self-perceived work ability in different ways, depending on whether they were working or not. Those who were working experienced their interaction with the workplace, and support from other actors, as a positive contribution to their work ability. Those not working described problems in their interaction with the workplace, such as lack of workplace support or conflicts, and lack of support from actors outside the workplace, that had a negative influence on their work ability.

Conclusions

Self-understanding and coping strategies, interaction with the workplace, support from actors outside the workplace, and social insurance regulations were intertwined categories, influencing each other and consequently the participants’ self-perceived work ability during and after occupational rehabilitation.

Working-age persons with health problems might have reduced work ability, leading to long-term or permanent sickness benefits, unemployment, or early retirement (Lagerveld et al., Citation2010). There is concern about the large number of persons on sickness benefits in Norway and many other Western countries (OECD, Citation2010). The number of persons on sickness benefits represents a challenge for these persons, their families and workplaces, and for the society as a whole (Alexanderson & Hensing, Citation2004; Pransky, Gatchel, Linton, & Loisel, Citation2005; Waddell, Citation2006). Musculoskeletal disorders and mental health problems are the main reasons for sickness absence and disability pension (OECD, Citation2010).

OCCUPATIONAL REHABILITATION

To include persons on sickness benefits in the working life, increasing emphasis has been put on occupational rehabilitation. A number of interventions are offered to persons on sickness benefits to enhance work ability, but there is limited knowledge about their effects (Palmer et al., Citation2012; van Oostrom et al., Citation2009). There is some evidence that interdisciplinary rehabilitation combined with workplace interaction can promote work ability and return to work (RTW) after sickness absence (Carroll, Rick, Pilgrim, Cameron, & Hillage, Citation2010; Hoefsmit, Houkes, & Nijhuis, Citation2012; Kuoppala & Lamminpaa, Citation2008; Norlund, Ropponen, & Alexanderson, Citation2009). Cooperation between the involved actors to reach common goals and strategies toward RTW are emphasized (Schandelmaier et al., Citation2012). Despite this knowledge, a large number of patients do not RTW after they have completed a rehabilitation program. Identifying factors that facilitate or inhibit improvement of work ability in relation to the rehabilitation process may be helpful in designing such interventions (Hedlund, Landstad, & Wendelborg, Citation2007; Selander, Marnetoft, & Asell, Citation2007).

FACTORS INFLUENCING WORK ABILITY

Work ability is a dynamic and relational concept resulting from the interaction of multiple dimensions that overlap and influence each other (Lederer, Loisel, Rivard, & Champagne, Citation2014). Work ability encompasses the physical, mental, social, environmental, and organizational demands of a person's work and his or her capacity to meet these demands (Fadyl, McPherson, Schluter, & Turner-Stokes, Citation2010). A great number of factors that influence work ability and RTW among persons on sickness benefits have been identified, both in quantitative systematic reviews (Blank, Peters, Pickvance, Wilford, & Macdonald, Citation2008; Cornelius, van der Klink, Groothoff, & Brouwer, Citation2011; Lagerveld et al., Citation2010; Selander, Marnetoft, Bergroth, & Ekholm, Citation2002) and in qualitative systematic reviews (Andersen, Nielsen, & Brinkmann, Citation2012; MacEachen, Clarke, Franche, & Irvin, Citation2006). Only modifiable factors such as self-perceived work ability and work-related factors can provide a sound basis for interventions (Cornelius et al., Citation2011). At the individual level, increased self-understanding and adaptive coping skills have been identified as important factors for regaining work ability and RTW (Franche & Krause, Citation2002; Haugli, Maeland, & Magnussen, Citation2011; Norlund, Fjellman-Wiklund, Nordin, Stenlund, & Ahlgren, Citation2013). Haugli et al. (Citation2011) found that increased self-understanding implied increased awareness of own identity, values, and resources. This may open up for new possibilities and choices, and new ways of acting to manage the life situation and the RTW process. Such learning and changing processes can be facilitated in occupational rehabilitation. Social and environmental dimensions influencing work ability include work tasks, work environment, labor market conditions, health care and social insurance services, regulations, and relationship between involved actors (Ilmarinen, Citation2009; Nordenfelt, Citation2008). Workplace support and cooperation between involved actors are seen as especially important for RTW (Andersen et al., Citation2012; MacEachen et al., Citation2006; Stahl, Svensson, Petersson, & Ekberg, Citation2010).

A rehabilitation program aims to assist a person to regain work ability to achieve a successful RTW process. This process is thought of as a behavioral change encompassing a series of events, transitions, and phases, in addition to the interactions with other persons and the environment (Young et al., Citation2005a). It comprises the person's self-perceived changes in work ability and changes in his or her readiness for RTW (Franche & Krause, Citation2002). RTW can be graded or a return to full-time work. Those who are not able to continue with their former work tasks may be able to resume work if the employer modifies their work tasks on a temporary or a permanent basis. If this is not an option, a person's chances of gaining new employment depends on the possibilities and demands in the labor market and the person's capacities for work.

SELF-PERCEIVED WORK ABILITY

RTW perceptions and self-perceived work ability among persons on sickness benefits have been identified as crucial for future RTW (Braathen et al., Citation2014; Iles, Davidson, & Taylor, Citation2008; Landstad, Wendelborg, & Hedlund, Citation2009; Reiso, Nygard, Brage, Gulbrandsen, & Tellnes, Citation2001). A person's perception of RTW and work ability should be viewed from a framework that incorporates the complexity of the RTW process, including the influence multiple actors and contextual factors have on what the person perceives as important (Franche & Krause, Citation2002; Loisel et al., Citation2005; Young et al., Citation2005a). These perceptions are a central basis for occupational rehabilitation (Grahn, Ekdahl, & Borgquist, Citation2000; Gard & Larsson, Citation2003; Harkapaa, Jarvikoski, & Gould, Citation2014). There is a need to unravel factors that may influence self-perceived work ability, to guide the focus of the rehabilitation process, and to provide tailored interventions (Harkapaa et al., Citation2014). Knowledge concerning self-perceived changes in work ability among persons attending occupational rehabilitation programs is limited (Andersen et al., Citation2012; MacEachen et al., Citation2006).

AIM

The aim of this study was to explore self-perceived change in work ability among persons attending occupational rehabilitation programs.

METHODS

Study setting

The study setting was at an inpatient occupational rehabilitation clinic in Norway. The clinic is a part of the specialist health service in Norway, and offers a 4-week occupational rehabilitation program. The program is offered to 18- to 67-year-old persons with multiple health problems in situations where medical treatment and interventions at the workplace have not resulted in sustainable RTW. The most common medical diagnoses are related to musculoskeletal and mental health problems. The persons are referred to the clinic by general practitioners, social insurance offices (NAV offices), or hospitals. Persons in the program are on long-term sickness benefits, or they are currently working with a history of earlier sickness absence and at risk of sickness absence recurrence. They are assessed as having a chance of being able to RTW. Exclusion criteria for the rehabilitation program were serious psychiatric disorders, undecided applications for disability pension, or insurance claims.

The rehabilitation program

The aim of the rehabilitation program is threefold: first, to change the direction of the person's focus from health problems and disability to an increased awareness of his or her own resources; second, to improve their way of coping with their health problems and disability; and third, to assist the cooperation between the actors (workplace, general practitioner, the NAV office, and others) in the RTW process, aiming at common goals and strategies for the person to RTW. The rehabilitation program is led by an interdisciplinary team (physician, nurse, sport pedagogue, physiotherapist, and work counselor), and the interventions are given partly in the form of group activities and partly as individual follow-up. The physical group activities included various exercises (outdoor activities, water training, spinning, gym, and stretching) as well as body awareness training and relaxation. Confidence, coping, and learning were important objectives for all physical activities offered. Educational sessions included topics such as work-related issues, exercise, diet, lifestyle, and awareness of relationship between thoughts, emotions and bodily reactions. The persons also attended individual and group-based counseling with a cognitive behavioral approach aiming to increase function and work ability and making goals and plans for RTW. Other types of individual follow-up were carried out based on the team's assessment of the need of each person and included individual consultations with the team members, the workplace, the NAV office, and the primary health care service. In consultations with the workplace and other involved actors, RTW options and plans were discussed. At the end of the program, an individual report was sent to the general practitioner and the NAV office.

In the Norwegian social insurance system, a person is entitled to sickness benefits if he or she is incapable of working due to disease, illness, or injury (The National Insurance Act, Citation1997). The sickness absence benefit is paid from the first day of absence for the maximum of 52 weeks, and is in general at the same level as the employment income. After the sickness absence period, a person can be granted work assessment allowance or disability pension, if the work ability of the person is reduced by 50% or more. Usually, these benefits equal about two-thirds of the employment income level. The employer has the primary responsibility for organizing the follow-up of the employees on sickness absence, whereas the employee is obliged to cooperate to find solutions that prevent unnecessary use of sickness benefits (The Work Environment Act, Citation2005). In addition, health personnel certifying sickness benefits and the NAV office have formal roles in the follow-up.

Study design and participants

The study was based on in-depth interviews with persons who had attended the 4-week inpatient occupational rehabilitation program in Norway. The interviews were conducted in 2012. The medical secretary at the rehabilitation clinic distributed an invitation letter to a strategically selected sample of 101 persons who had completed the program, and who had an employment contract when they attended the program. Twenty-two persons returned a written consent (21.8%), and interviews were conducted with 17 of them. We included persons until we had sufficient information about different RTW processes among those who had returned to work full time or part time in combination with partial sickness benefits, and those who did not RTW. Interviews were conducted with 3 men and 14 women; their age ranged from 32 to 62 years (median 48.5 years) (Table ). Nine participants had completed higher level of education (university/university college), and eight had completed elementary or secondary education. The participants were employed in various occupations. Most were in person-related and administrative jobs at hospitals, schools, or municipalities, and some were in manual jobs. Their diagnoses included depression, anxiety, fatigue, low back pain, fibromyalgia, and other muscular pain conditions. Many participants reported several health problems related to muscular pain conditions, depression, and fatigue. They described a close relation between their health problems and challenges in past or present life. Such challenges were at the personal, family, or workplace level. Shortly before the program, 10 were on full sickness benefit; 4 were working reduced hours combined with partial sickness benefit; and 3 were working full time. Two of the participants had a partial permanent disability pension. At the time of the interviews, 6 months after the program, six were on full sickness benefit; six were working reduced hours combined with partial sickness benefit; and five were working full time. Compared to their working hours before rehabilitation, eight participants had increased their working hours, four had reduced their working hours, and five were on the same level.

Table I Demographic and work participation characteristics of the study participants who had attended a Norwegian occupational rehabilitation program.

Interviews

The interviews addressed the participants’ perceptions of changes in work ability during and after the rehabilitation program. The participants in the study were informed about the purpose of the interview, that participation was voluntary, and that they were free to end the interview at any time. They gave their permission for the interview to be audiotaped and were assured confidentiality and that data would be securely stored. The South East Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics in Norway approved the study (Reference number 2010/1901b).

The interviews were based on a semi-structured written guide with open-ended questions (Table ). The guide was developed by the authors. It was discussed with a user representative (patient delegate), tested on two persons in the program, and thereafter adjusted to ensure validity of the questions asked. The two test interviews were included in the total data collection and data analysis, because only small adjustments of the interview guide were made. The participants answered questions about how they perceived their work ability and possible changes in their work ability, related to their former and current situation regarding work and RTW goals. Some related their work ability to their original job, others to new work tasks, a new job, or to their possibility of securing a new job. Flexibility in the interviews was emphasized to give the participants an opportunity to tell their story, and to ask follow-up questions directly related to themes important to the participants. Two of the study authors (TNB and LH) conducted the interviews, which lasted for 45–90 minutes. The authors who conducted the interviews were not staffed in the rehabilitation program. The interviews were conducted over the telephone, at their workplace, in the participants’ homes, or in a neutral place near home, based on the wish of the participants. We emphasized confidence and trust in the interview situation to ensure validity of the data collection.

Table II Semi-structured interview guide exploring self-perceived change in work ability among persons attending a Norwegian occupational rehabilitation program.

Analysis

The interviews were transcribed verbatim. Data were analyzed by the systematic text condensation method, which is a strategy for qualitative analysis aiming at thematic analysis of meaning and content of data across cases (Malterud, Citation2012). This method is a pragmatic approach where the experience of the participants, as expressed by them, is presented. This method holds an explorative ambition to present vital examples from persons’ life worlds. It implies analytic reduction with specified shifts between decontextualization and recontextualization of data. The analysis was conducted through the following four steps: (1) reading all the material to obtain an overall impression and bracketing previous preconceptions; (2) identifying units of meaning, representing different aspects of self-perceived changes in work ability, and coding for these; (3) condensing the content of each of the coded groups; and (4) summarizing the contents of each meaning unit to generalize descriptions and concepts concerning self-perceived changes in work ability. In Step 4, the findings were recontextualized to make sure the synthesized results reflected the original contexts, and were compared with existing research. Our analysis strategy was data driven, although supported by earlier models of work ability and the RTW process (Lederer et al., Citation2014; Loisel et al., Citation2005; Young et al., Citation2005a). The stepwise analysis of the interviews was conducted during the data collection. The steps in the analysis were performed in several sequences, as suggested by Malterud (Citation2012). This was done to sustain an overview of the empirical data and to sharpen the focus and aim. In the first sequence of analysis, we included five participants. This preliminary analysis was limited to central themes, codes, and meaning units (analysis Step 1 and 2). The preliminary analysis was also used to inform further sampling. In the second sequence, we added five more participants, and investigated whether the same themes were identified, whether any new themes emerged, and whether we still needed more participants. We stopped inclusion of new participants when we assessed that the sample was sufficiently large and varied to elucidate the aim (Malterud, Citation2012), in our case 17 participants. In the third sequence of analysis, we included all 17 participants. All analysis steps described by Malterud were performed. In addition to the steps of analysis, we synthesized the individual transcripts into individual summaries, in order to maintain an overview of each participant's self-perceived change in work ability. The qualitative data analysis software NVivo (version 10) was used to organize the material, code units of meaning, and to secure a systematic and transparent approach. All authors were part of the data analysis. The first author (TNB) conducted the coding and the translation from Norwegian into English. The transcripts were read separately by the authors and units of meaning, condensations, and summations were discussed, adjusted, and documented during several meetings, contributing to validity.

RESULTS

The self-perceived change in work ability from the start of the rehabilitation program through the following months showed great variability between the participants. These change processes were unique for each participant, and were mediated by different factors. Self-perceived change in work ability was influenced by the participants’ self-understanding and coping strategies, interaction with their workplace, support from actors outside the workplace (the NAV office, the health care service, and close family), and social insurance regulations. The participants expressed retrospectively that during the rehabilitation program they increased their self-understanding and improved their coping strategies. The persons interviewed described their interaction with the workplace and support from other actors differently depending on whether they were working or not. Those working felt they were able to cope with challenges and demands at work after attending the rehabilitation program. Their interaction with the workplace and support from other actors promoted their self-perceived work ability. Nevertheless, some said they were balancing on an edge in terms of what they could cope with. Participants not working described problems in their interaction with the workplace, such as lack of workplace support or conflicts at work, and lack of support from actors outside the workplace. The categories that emerged from the data are presented in . In the following paragraphs, the identified categories are summarized.

Figure 1 Dimensions influencing self-perceived change in work ability among persons attending a Norwegian occupational rehabilitation program. Categories and subcategories are presented.

Self-understanding and coping strategies

The participants expressed that they increased their self-understanding and improved their coping strategies during the rehabilitation program. Being challenged on self-understanding and learning from activities and encounters in the rehabilitation program facilitated such changes. Increased self-understanding comprised increased awareness of own thoughts, emotions and bodily reactions, and increased awareness of the relationship between these. The persons interviewed, especially those working, described how during the rehabilitation program they got an increased awareness of own capacity, own values, and how to live in accordance with own values. They expressed that they managed to take control of their situation and make important choices and priorities.

I have become more aware of myself, my body and how I react, especially in situations where I am exhausted and stressed … I am more aware of my capacity, both my strengths and weaknesses. (woman, 59 years, partial work participation at time of interview)

was important to me to understand that I could not carry on like before. It was a real eye-opener, when I became aware that I was actually running myself down. (woman, 50 years, full work participation at time of interview)

I realized what was important to me and made different priorities than before. (man, 45 years, partial work participation at time of interview)

I have regained control of myself and my situation, and have filtered out things that are not important to me … It has been important to me to become physically active, have a healthy diet and to set limits in everyday life. (woman, 47 years, partial work participation at time of interview)

Through increased self-understanding, the participants improved their coping strategies during and after the program. They developed and used new coping strategies, such as taking breaks and setting limits in everyday life. They felt they coped better with stressful situations both at home and at work after the program. Before the program, many described lack of structure in everyday life. This was experienced as destructive, adding to the negativity of being ill. During the program, they kept the days firmly structured and they felt that this increased their energy and general functioning. Many maintained the structure when they got home, for example, having regular physical activity, stable sleep routines, and a healthier diet. Some also learned that when thinking and doing things differently, the response from their surroundings changed. Several reported that they had strengthened their self-confidence, enthusiasm, and self-satisfaction, and that they felt stronger and more flexible. Several found tools they could use to become more active in their own life, get out of a vicious circle, and get on with their life.

When I got back home – meeting everyday life, I had strategies I did not have before. My surroundings was the same as I had earlier. It is about handling it differently than before – saying, thinking and doing things differently. Things that are good to me. The response from my surroundings is different when I change my strategy … I have more power and energy … and my self-confidence have improved. (woman, 60 years, partial work participation at time of interview)

I got a real kick, making me move on, and now things go easier. (woman, 37 years, full work participation at time of interview)

Being challenged on self-understanding and learning from activities and encounters in the program

Several components of the program contributed to increased self-understanding and improved coping strategies. Participants expressed that they were pleased with the focus on resources and possibilities in the program, rather than on the medical diagnosis. They felt that they were challenged to increased awareness of own ways of thinking and acting. Some pointed out that they received well-informed explanations regarding their health problem and were reassured to resume normal activity and RTW. Several also experienced that the physical activities and the feedback from the rehabilitation professionals contributed to increased self-understanding and improved coping strategies.

It was good that the rehabilitation professionals focused on me as a human being, rather than the disease. I first thought; “They must know I am ill” … However, in retrospect I have thought that it was good they focused so little on disease and more on what I managed and what I was able to. I think they (the professionals) helped me to change my direction … I was challenged to think about what I can change and what areas I cannot change. (woman, 59 years, partial work participation at time of interview)

I was challenged in the activities, but experienced coping and discovered that I had capacity to achieve more than I believed. (man, 50 years, full work participation at time of interview)

The group dynamic between the peers in the rehabilitation program also contributed to increased self-understanding and improved coping strategies. The participants said that the group members supported each other and helped each other to participate more in social settings. Several of the persons interviewed described that they received understanding, comfort, and challenges from their group members. Such feedback helped them to a better understanding of their own challenges.

Among participants not working, few described elements of such changes in self-understanding and coping strategies during the program. Instead, some became more aware of their own limitations and that they were not ready to RTW. They were referred to further medical assessment or treatment and chose to focus more on their health and activities promoting their health than on RTW. Furthermore, they talked about how to accept their reduced work ability.

I became conscious about speaking more positive about myself, be more satisfied with what I manage, and feel that I have abilities in other areas than at work … And to accept that some days I am not capable of anything, but to be satisfied despite my reduced abilities … And to enjoy the little things I can manage. (woman, 49 years, no work participation at time of interview)

I got a diagnosis that I accepted. I adjusted to it … I accepted it and felt it was right. That I was not ready to RTW, which I thought I would be when I came into the rehabilitation program. That it was going to take longer than I had thought. I had realized that I did not have the capacity to work that I thought I had. (woman, 59 years, no work participation at time of interview)

Some persons experienced problems in the encounters with the rehabilitation professionals during the program. A few did not get the individual consultations after the initial assessment as they had expected.

I experienced no good match with one of the rehabilitation professionals, and I did not have the confidence that he/she could help me. (woman, 62 years, no work participation at time of interview)

My needs were not understood early enough, and the individual adaptation was too general. (woman, 43 years, partial work participation at time of interview)

Interaction with the workplace

The participants’ descriptions of interaction with the workplace comprised experiences from communication with the workplace during the rehabilitation program, workplace support, and conflicts.

Communication during the rehabilitation program

Retrospectively, several participants expressed that communication with their workplace during the rehabilitation program was helpful. The work counselor at the rehabilitation clinic assisted in the communication. The participants said that they through the contact with their leader could discuss needs and opportunities for work modifications. They also made agreements before returning to work.

Through the contact we got an understanding of what was important and helpful to me when I returned to work, and made arrangements before I returned. The agreements were implemented, and it was a very good experience to come back to work. (woman, 43 years, partial work participation at time of interview)

Some of the participants not working expressed retrospectively that they had expected more assistance from the rehabilitation team regarding communication with their workplace.

I informed my employer about what I considered was needed in order to return to work. Since there was no formal written feedback to my employer after the program, the employer had limited possibilities. (woman, 62 years, no work participation at time of interview)

I expected more assistance from the rehabilitation team regarding the employer dialogue, because work modifications were difficult to achieve. (woman, 32 years, no work participation at time of interview, work training)

Workplace support

The persons interviewed described support from their leader as important for their work ability. Those who experienced that their leader had been available for them and showed understanding toward their situation, and those who felt that they were wanted back at work, perceived that their work ability was promoted. Some participants experienced that support from colleagues and the positive value of being part of the social fellowship at work promoted their RTW. Especially, working participants experienced that work modifications had a positive impact. This included changes in work days, work hours, work tasks, responsibility and physical aspects. These modifications were experienced as essential to be able to cope with work. For example, a child welfare officer did not cope with the mental and emotional demands of her job. She agreed with her leader and human resource personnel to look for a job outside child welfare. She was offered a job as a parking warden, and the changes in work tasks promoted her self-perceived work ability.

The leader and I knew I had the ability to work, only not in my former job. The new job is completely different. Earlier I struggled with the mental and emotional demands. Now, my work tasks are great and no longer difficult to me. (woman, 42 years, full work participation at time of interview)

Several of those working reduced hours had had the possibility to modify their original jobs and gradually adjust the work demands according to their capacity.

I was fortunate to be allowed modified work, and gradually approached my regular work tasks in a pace I was able to cope with. (woman, 59 years, partial work participation at time of interview)

Currently, I do not have sole responsibility to keep and settle accounts for companies or responsibility regarding deadlines … This has made it possible for me to work 60%. If the work had not been modified, I guess I would have been 100% on sickness absence. (woman, 43 years, partial work participation at time of interview)

The participants not working had different experiences regarding workplace support. Some reported difficulties being understood and to obtain an agreement with their leader. They felt they had to return to full work with restricted possibilities for getting the work modifications they needed. A headmaster experiencing lack of workplace support did not feel ready to RTW:

I asked (the employer) if anything had happened during the last year, and the answer was no. It was the same. Then I felt that I sort of collapsed … It is not a job for me, at least not a job where I can stay in good health … I still need help to clear my thoughts. I need help to clarify my circumstances, what I can cope with myself and what I need help coping with. (woman, 62 years, no work participation at time of interview)

In addition, some participants not working did not cope with the modified work or work training they were offered after the rehabilitation program, because they experienced that their health problems were aggravated when working.

When I got there (work training), I got outburst of anxiety and did not manage to control myself. I was standing in the stockroom, hiding … I wanted to terminate the whole thing … I completed the arranged period, but only for about one and a half hour per day … Now I am waiting for a meeting at the NAV office … We are simply going to talk about trying to apply for a permanent disability pension. (woman, 49 years, no work participation at time of interview)

Conflicts

Several participants described conflicts at their workplace that influenced their work ability. Some were resolved, whereas others remained unresolved. Conflicts that were not resolved had a negative impact on self-perceived work ability. Participants involved in conflicts expressed that they had problems accepting their work situation, and were unsure about their RTW options. A teacher involved in a conflict at work did not RTW after the rehabilitation program. She was offered another position, but did not accept it. She tells:

I got into further treatment where I have worked to clear my thoughts regarding work and my reactions concerning things that happened at work … I feel I am not where I should be. I cannot talk about my work situation without finding it difficult … Should I fight to return to the original job or should I just accept the situation? (woman, 59 years, no work participation at time of interview)

Some persons returned to work after the program, but experienced difficult events at work and then returned to a new period of sickness absence. An auxiliary nurse returned to part-time work after the program, but she reacted in an unacceptable way in an emotionally challenging situation for her in communication with a patient. Her leader sent her a written complaint. Subsequently, she was certified sick again. She felt her leader handled the situation unprofessionally. Her leader was willing to offer her modified work within the nursing home, but instead she decided to look for new jobs while she was on sickness benefit.

After the event, I went back into full sickness absence. I was not well … It was a challenge just to come to the workplace after the event … I felt all the eyes looking at me, and thought I was the “bad wolf” … I felt the new tasks they were offering me afterwards were going to be difficult to me, moving from my work as auxiliary nurse to help with different tasks, on top of the other colleagues … I do not wish to go back to that workplace. I think it is healthily for me to get away, to a new environment, and deal with new people. (woman, 48 years, no work participation at time of interview)

The participants’ experiences from the interaction with the workplace reflect the importance of establishing a close contact between the workplace and the participant during the rehabilitation program. The rehabilitation professionals can assist this communication, and ensure that different aspects of the work situation are clarified, such as possibilities for work modifications or potential work conflicts. They could also facilitate a discussion of realistic RTW goals and strategies.

Support or lack of support from actors outside the workplace

The participants also expressed that support from actors outside the workplace, or lack of such support, influenced their work ability. These actors could work in the health care service, at the NAV office, or be close family. Some participants were satisfied with the support from the health care service that focused on treatment and further clarification of medical diagnosis. Participants experienced the NAV office as a key actor when a participant terminated the employment contract. Those experiencing support from the NAV office felt that their work ability was promoted when the NAV office was active in decision-making regarding possible RTW interventions. Some participants expressed that cooperation between different actors was important, giving them new possibilities in the labor market, for example, through work training and education. One example is the experience of an industrial worker. He received support from the NAV office and other service providers after having terminated his employment contract. They arranged appropriate work training, gave him encouraging feedback, and supported him when he decided to start studying to get into a new job.

I met people who saw opportunities and lifted me up. (man, 53 years, no work participation at time of interview, student)

On the contrary, some participants described lack of support from NAV and the health care service after the rehabilitation program. They missed local coordination after the program, and experienced that waiting for therapy and insufficient follow-up influenced their work ability in a negative way.

There has been too long time from I ended therapy one place until I started the next. It feels like I need to start all over again. When I attend such a rehabilitation program, it should be conditional that I receive the follow up needed afterwards, when I still am in such a “flow.” I have invested in it, and have mobilized my willpower, and then there is a terrible disappointment if it takes too long before the next round is coming. (woman, 62 years, no work participation at time of interview)

At the family level, some of the persons interviewed described that support from their close family helped them in the RTW process. They were challenged in a positive way and got feedback about improvements in their capacity and lifestyle changes. This helped them to maintain new coping strategies. However, other participants expressed that strain from the family situation negatively influenced their work ability. A woman working full time described her difficulties coping with the demands both at work and at home:

I have a high strain at home, and difficulties to meet the demands both at home and at work. The workplace is surprised of how much absence I need and they have asked me to consider reducing working hours. However, if I should only work 80%, from where can I get my last 20% (of income) then? I am not disabled for work. So I am not sure about what to do. (woman, 42 years, full work participation at time of interview)

The descriptions given by these participants point out the importance of continued and coordinated support from the health care service, the NAV office, and close family after the rehabilitation program to succeed with the RTW process. Some participants also expressed that follow-up from the professionals in the rehabilitation program after the 4-week period could have assisted them in their process toward sustainable RTW.

Social insurance regulations

Social insurance regulations and sickness benefit certifications also seemed to affect self-perceived work ability. Some participants expressed that regulations and decisions regarding sickness benefits made by the NAV office were important for their own RTW decisions. A teacher's application for partial sickness benefit was declined because her work ability was not considered to be reduced by at least 50% due to illness or injury, as required by the regulation. Because she was dependent on the income, she chose to return to full-time work instead of part-time work as she had planned, even though it challenged her health situation. For her, the economic incentive facilitated a faster return to full-time work.

I started 70% partial work after the rehabilitation program, but soon afterwards I was informed that my application for partial sickness benefit was not approved, and I started working full time. It was a challenge to start working full time. It had some costs for me. But I am so dependent on the income. (woman, 50 years, full work participation at time of interview)

On the contrary, some participants told about prolonged sickness benefit certifications. A nurse working part time had been certified for partial sickness benefit for the next 5 months. She expressed that she had these months before she would consider returning to full-time work.

The sickness benefit is approved for the next five months. That is the time I have got. (woman, 47 years, partial work participation at time of interview)

These examples illustrate that the social insurance regulations, and how these regulations are put into practice through decisions made by NAV offices and certifying physicians, influence the participants’ RTW decisions.

DISCUSSION

Self-perceived change in work ability during and after the rehabilitation program was influenced by the participants’ self-understanding and coping strategies, their interaction with the workplace, support or lack of support from actors outside the workplace, and social insurance regulations. They were intertwined categories. Being challenged on self-understanding and learning from activities and encounters in the rehabilitation program facilitated increased self-understanding and improved coping strategies. These changes influenced behavior and subsequently the response from the surroundings. Conversely, interaction with the workplace and support from other actors affected self-understanding and coping strategies. Participants who were working described that their interaction with the workplace and support from other actors had contributed to their improved work ability. Participants not working described that problems in their interaction with the workplace, such as lack of support or conflicts, and lack of support from actors outside the workplace, negatively influenced their work ability.

These findings suggest that it is essential to examine the importance of the elements in the person-environment interaction to fully grasp changes in work ability during and after rehabilitation. Other studies support these findings (Ilmarinen, Citation2009; Landstad et al., Citation2009; Lederer et al., Citation2014; Loisel et al., Citation2005; Norlund et al., Citation2013). A person's work ability is multidimensional and dynamic, indicating that professionals working with occupational rehabilitation should address several influential factors simultaneously to assist the person to improve his or her work ability. A multidimensional approach can lead to new ways to address the full spectrum of conditions positively or negatively affecting RTW. This is also in line with previous research showing that multimodal and interdisciplinary rehabilitation can increase work ability and RTW (Hoefsmit et al., Citation2012; Kuoppala & Lamminpaa, Citation2008; Norlund et al., Citation2009). Furthermore, this study provides descriptions of different RTW processes after an occupational rehabilitation program, such as resuming ordinary work, getting into a new job, moving back into sickness benefit, and termination of the employment contract. These descriptions reveal mechanisms that hinder or promote the RTW process. Several implications for rehabilitation will be addressed in the following discussion.

Self-understanding and coping strategies

Our results indicate that increased self-understanding and development of coping strategies are important for a person to regain work ability. Increased self-understanding has earlier been pointed out as a central aspect in rehabilitation and RTW processes (Fjellman-Wiklund, Stenlund, Steinholtz, & Ahlgren, Citation2010; Haugli et al., Citation2011). Haugli et al. (Citation2011) concluded that persons who had reentered work after occupational rehabilitation, emphasized the experience of increased awareness of own identity, values, and resources as an important step toward successful RTW in spite of their health problems. Our findings are also in line with the findings of Norlund et al. (Citation2013), who stated that insights and adaptive coping skills were vital to regain work ability among persons with exhaustion disorder. Our findings related to self-understanding and coping strategies are in accordance with important processes of change in the readiness for RTW model, entailing how people change to progress through stages of readiness for RTW (Franche & Krause, Citation2002). Increased self-understanding and improved coping strategies can promote changes that enable a person to improve work ability and increase readiness for RTW. Being challenged on self-understanding and learning from activities and encounters in the rehabilitation program facilitated such changes. Our study supports that rehabilitation programs should address increased awareness of own thinking and behavioral patterns, own resources, possibilities, and physical activity to promote self-perceived work ability and the likelihood of RTW. In line with these results, other studies underline that cognitive behavioral approaches and physical activity are important factors for RTW among persons with musculoskeletal disorders (Costa-Black, Citation2013; Dionne et al., Citation2013; Oesch, Kool, Hagen, & Bachmann, Citation2010). Rehabilitation professionals should enable the person to become more active in, and take charge of his or her own RTW process. This is consistent with components in the person-centered approach where the person is regarded as an active participant, power and responsibility are shared, and focus is on ability rather than disability (Leplege et al., Citation2007). Furthermore, our findings indicate that support from peers in the program contributes to increased self-understanding. This is in accordance with previous studies (Fjellman-Wiklund et al., Citation2010; Haugli et al., Citation2011).

Some participants experienced relational problems with professionals at the rehabilitation clinic and were less content with the individual adaptations in the rehabilitation program. This might reflect some of the challenges occurring during a rehabilitation process. Assisting a person to identify what he or she actually needs in order for him or her to regain work ability, and then to tailor the rehabilitation according to these needs within a group setting are challenging. The quality of the therapeutic alliance seems to be an important precondition to deliver tailored interventions, and to increase the likelihood of RTW (Mussener, Svensson, Soderberg, & Alexanderson, Citation2008; Soderberg, Jumisko, & Gard, Citation2004).

Interaction with the workplace

Positive experiences regarding workplace support facilitated self-perceived work ability, in line with previous research (Andersen et al., Citation2012; Campbell, Wynne-Jones, Muller, & Dunn, Citation2013; MacEachen et al., Citation2006). Problems in the interaction with the workplace, such as lack of support or conflicts, became important barriers to RTW. In some persons it also contributed to recurrence of sickness absence, in accordance with findings in previous studies (Arends, van der Klink, van Rhenen, De Boer, & Bultmann, Citation2014; Noordik, Nieuwenhuijsen, Varekamp, van der Klink, & van Dijk, Citation2011). Our findings indicate that the rehabilitation professionals should emphasize and address the person's situation at the workplace and incorporate the workplace into the rehabilitation process. This is in accordance with previous research concluding that RTW interventions need to take social relations among workplace actors into account (Tjulin, MacEachen, & Ekberg, Citation2010). The employers are in charge of workplace modifications, and their opinions and interests are decisive for the employee's RTW possibilities. Another study (Seing, Stahl, Nordenfelt, Bulow, & Ekberg, Citation2012) described that the employers have the “trump card,” illustrating the unequal power among the cooperating actors in meetings held to discuss the work ability and rehabilitation needs of an employee on sickness absence. A previous literature review (Shaw, Hong, Pransky, & Loisel, Citation2008) concluded that RTW depends more on work modification, communication, and conflict resolution rather than medical training and treatment. Thus, the rehabilitation professionals need to listen to the person's thoughts and feelings of RTW, obtain the perspective of the employer and other workplace actors, and then facilitate a constructive communication to promote a successful RTW (Lydell, Hildingh, Mansson, Marklund, & Grahn, Citation2011; Young et al., Citation2005b).

In our study, participants not working experienced that their distance to their original job had increased after the rehabilitation program. Some experienced a defeat regarding the return to their workplace and terminated their employment contract. They were concerned about their future possibilities for participation in working life, thus describing their employability more than their work ability (Nilsson & Ekberg, Citation2013). Hence, results from this study indicate that the rehabilitation program needs to be tailored to the individual situation. In some cases it would be reasonable to promote return to the same workplace, whereas in others job mobility may be a better option (Ekberg, Wahlin, Persson, Bernfort, & Oberg, Citation2011). Some consider seeking other jobs because of earlier experiences at their workplace or because they suffer from ill health due to their job. However, changing job may be strenuous and risky from a financial and job security perspective. Changes in the labor market, including changing demands on employees in working life, have reduced the possibilities for finding new permanent jobs, and persons on long-term sickness absence may perceive themselves as more vulnerable when seeking new employment. Thus, knowledge of the person's resources in relation to both the workplace and the labor market is important when developing tailored RTW interventions.

Support or lack of support from actors outside the workplace

Support from the NAV office, the health care service, and close family promoted self-perceived work ability. The importance of cooperation between the involved actors in our study is in line with earlier RTW research (MacEachen et al., Citation2006; Stahl et al., Citation2010). As in previous research, experiences of insufficient coordination and follow-up after the program had a negative influence on self-perceived work ability and RTW (Andersen et al., Citation2012; Landstad, Hedlund, Wendelborg, & Brataas, Citation2009). Some of the problems in the follow-up and coordination after the rehabilitation program may be due to lack of time, resources, or lack of decision-making authority available to the employees in the NAV office or in the health care service. Lack of coordination may also be due to different perspectives and approaches to work ability among the involved actors. Apparently, the rehabilitation professionals could increase their efforts of cooperation with the involved actors in order to facilitate a common understanding and strategy. Rehabilitation professionals have an important role as mediators between the person, the workplace, and other involved actors (Briand, Durand, St-Arnaud, & Corbiere, Citation2008). Enhanced cooperation between these actors might further improve the RTW process for persons attending occupational rehabilitation programs. One possibility is to ensure this cooperation by the use of a RTW coordinator who can support participants in the rehabilitation process during and after such a rehabilitation program. This might facilitate a sustainable RTW and prevent sickness absence recurrence (Franche et al., Citation2005).

Some participants also expressed that support from close family promoted their RTW process, in line with previous research (Jakobsen & Lillefjell, Citation2014). However, family burdens could influence self-perceived work ability negatively. Earlier research has shown that especially women experience family burdens and caring responsibilities as factors influencing sickness absence (Batt-Rawden & Tellnes, Citation2012a, Batt-Rawden & Tellnes, Citation2012b). The importance of the family indicates that rehabilitation professionals should consider the whole life situation of the person in the RTW process.

Social insurance regulations

Social insurance regulations and sickness benefit certification might influence self-perceived work ability and RTW decisions in different ways. We found that the denial of an application for sickness benefit, in addition to financial strain, contributed to the decision of returning to work sooner than planned. Such economic incentives for RTW are not surprising. However, for some persons this might increase the risk of sickness absence recurrence (Pransky et al., Citation2000). On the contrary, some participants had been certified long periods of sickness benefits. This may lead to unnecessary long periods of sickness absence. Prolonged sickness benefit certifications may lead to negative health effects, compared to the potential health benefits of working (Dunstan, Citation2009; Waddell & Burton, Citation2006). Previous research has shown that physicians experience sickness benefit consultations and certifications as problematic (Winde et al., Citation2012). When persons on sickness benefits consider RTW, they are weighing pros and cons of returning to work depending on their perceptions of own resources, earlier experiences with their surroundings, and their economic situation (Askildsen, Bratberg, & Nilsen, Citation2002; Franche & Krause, Citation2002). In addition, the perception of the value of work, own career, work ethics, and life outside work might influence the decisional balance when RTW opportunities and consequences are considered. Thus, the impact of social insurance regulations on self-perceived work ability should be analyzed in conjunction with other influencing factors. Important questions are whether the social insurance regulations in some cases can hinder or promote RTW, and whether the involved professional actors have sufficient knowledge about the health benefits of returning to work.

Methodological considerations

The findings gained in this study increase knowledge about self-perceived change in work ability among persons in similar occupational rehabilitation programs. However, the participants were only recruited from one rehabilitation program, which limits the external validity of the study. Furthermore, one should be careful about transferring the results to countries with different social insurance regulations. As aimed for in the data collection, the included participants varied according to work status at the time of the interviews. However, only 3 of 17 participants were male, which is a limitation to the study. Normally, about 34% of the persons in the program are men (Oyeflaten, Lie, Ihlebaek, & Eriksen, Citation2014). It is not clear why so few men wanted to take part in the study. One implication of this limitation might be that mechanisms and variations in men's self-perceived work ability are not revealed. Previous research has found sex differences regarding RTW (Cote & Coutu, Citation2010; Lillefjell, Citation2006), and such knowledge must be taken into account in designing rehabilitation interventions. In addition, the proportion of persons consenting participation in the study was low, and may have led to selection bias. A possible implication of this is that certain aspects of changes in self-perceived work ability were not elucidated. We did not have information to compare those that returned the written consent with those who did not. We only included participants with an employment contract at the start of the program. For patients without an employment contract, changes in self-perceived work ability are probably different from the findings in this study. In addition, this study addressed self-perceived change in work ability in persons with different types of medical diagnoses, and we did not focus on medical treatment. However, dimensions related to specific medical diagnoses should also be carefully considered in the rehabilitation, because different medical diagnoses influence the RTW process (Cornelius et al., Citation2011; Gjesdal, Bratberg, & Maeland, Citation2009; Selander et al., Citation2002).

The wording in the information letter about the study, and the way we asked questions in the interviews, reflected our point of view on work ability and RTW. This view may have influenced whom we recruited and how the participants responded. In addition, the interviewers’ relation to the rehabilitation clinic may have influenced the questions asked and the answers of the participants. All authors had experience with rehabilitation and RTW research, and three of the authors had experience with qualitative research. Three of the authors (TNB, ME, and LH) had a scientific position at the rehabilitation clinic but were not part of the rehabilitation staff. We did not experience any pressure from the employer connected to this study, but cannot deny that we unconsciously have been influenced by norms, values, and etiquette for polite behavior at the workplace. Our experience and closeness to the field increased our possibility to acquire knowledge and understand the phenomenon being studied. However, being close to the research field and the data can make it difficult to keep sufficient analytical distance.

Interviews were conducted 6 months after the rehabilitation program, and the time factor may represent a recall bias. On the contrary, the participants’ descriptions showed that important changes still took place 6 months after the program. This demonstrates that the RTW processes are complex and time-consuming. Follow-up interviews could have enriched the data in the study capturing the sustainability of the change processes. Follow-up interviews could also have given opportunities for reflection, maturation, and further discussion about important themes, leading to more in-depth analysis.

CONCLUSIONS

The aim of the study was to explore self-perceived change in work ability among persons attending occupational rehabilitation programs. Self-perceived change in work ability was influenced by persons’ self-understanding and coping strategies, interaction with the workplace, support or lack of support from actors outside the workplace, and social insurance regulations. These dimensions were intertwined influencing each other. To be challenged on self-understanding and coping strategies through activities and encounters with professionals and peers in the rehabilitation program seem important to regain work ability. The results of the study support that rehabilitation professionals should address increased awareness of the participants’ thinking and behavioral patterns, their resources and possibilities, and physical activity. Our findings support a multidimensional approach to assist a person to regain work ability and indicate that professionals in occupational rehabilitation should address several influential factors simultaneously. Furthermore, rehabilitation professionals should increase their efforts of cooperation with the workplace, the social insurance office (NAV), and the health care service to promote work ability. The study has contributed with knowledge about how the interaction between the person and the different actors in the surroundings hinders or promotes self-perceived work ability and RTW. Such knowledge can be applied to develop tailored occupational rehabilitation programs.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST AND FUNDING

The National Centre for Occupational Rehabilitation in Norway financed this research project. None of the authors were involved in the rehabilitation of the participants, but three of the authors (TNB, ME, and LH) had a scientific position at the rehabilitation clinic. The authors’ interest and knowledge in the field and the relation to the rehabilitation clinic have influenced the questions and dialog in the interviews and the analysis.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Søren Brage, Marianne Hedlund, and colleagues at the National Centre for Occupational Rehabilitation for helpful assistance.

REFERENCES

- Alexanderson K., Hensing G. More and better research needed on sickness absence. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health. 2004; 32: 321–323.

- Andersen M.F., Nielsen K.M., Brinkmann S. Meta-synthesis of qualitative research on return to work among employees with common mental disorders. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health. 2012; 38: 93–104.

- Arends I., van der Klink J.J., van Rhenen W., De Boer M.R., Bultmann U. Predictors of recurrent sickness absence among workers having returned to work after sickness absence due to common mental disorders, Scandinavian Journal of Work. Environment & Health. 2014; 40: 195–202.

- Askildsen J.E., Bratberg E., Nilsen Ø.A. Unemployment, labour force composition and sickness absence. 2002; Bergen, Norway: Department of Economics, University of Bergen.

- Batt-Rawden K.B., Tellnes G. Social causes to sickness absence among men and women with mental illnesses. Psychology. 2012a; 3: 315–321.

- Batt-Rawden K.B., Tellnes G. Social factors of sickness absences and ways of coping: A qualitative study of men and women with mental and musculoskeletal diagnoses, Norway. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion. 2012b; 14: 83–95.

- Blank L., Peters J., Pickvance S., Wilford J., Macdonald E. A systematic review of the factors which predict return to work for people suffering episodes of poor mental health. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation. 2008; 18: 27–34.

- Braathen T.N., Brage S., Tellnes G., Oyeflaten I., Jensen C., Eftedal M. A prospective study of the association between the readiness for return to work scale and future work participation in Norway. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation. 2014; 24: 650–657.

- Briand C., Durand M.J., St-Arnaud L., Corbiere M. How well do return-to-work interventions for musculoskeletal conditions address the multicausality of work disability?. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation. 2008; 18: 207–217.

- Campbell P., Wynne-Jones G., Muller S., Dunn K.M. The influence of employment social support for risk and prognosis in nonspecific back pain: A systematic review and critical synthesis. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health. 2013; 86: 119–137.

- Carroll C., Rick J., Pilgrim H., Cameron J., Hillage J. Workplace involvement improves return to work rates among employees with back pain on long-term sick leave: A systematic review of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of interventions. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2010; 32: 607–621.

- Cornelius L.R., van der Klink J.J., Groothoff J.W., Brouwer S. Prognostic factors of long term disability due to mental disorders: A systematic review. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation. 2011; 21: 259–274.

- Costa-Black K.M. Loisel P., Anema J.R. Core components of return-to work interventions. Handbook of work disability. 2013; New York: Springer. 427–440.

- Cote D., Coutu M.F. A critical review of gender issues in understanding prolonged disability related to musculoskeletal pain: How are they relevant to rehabilitation?. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2010; 32: 87–102.

- Dionne C.E., Bourbonnais R., Fremont P., Rossignol M., Stock S.R., Laperriere E. Obstacles to and facilitators of return to work after work-disabling back pain: The workers’ perspective. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation. 2013; 23: 280–289.

- Dunstan D.A. Are sickness certificates doing our patients harm. Australian Family Physician. 2009; 38: 61–63.

- Ekberg K., Wahlin C., Persson J., Bernfort L., Oberg B. Is mobility in the labor market a solution to sustainable return to work for some sick listed persons?. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation. 2011; 21: 355–365.

- Fadyl J.K., McPherson K.M., Schluter P.J., Turner-Stokes L. Factors contributing to work-ability for injured workers: Literature review and comparison with available measures. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2010; 32: 1173–1183.

- Fjellman-Wiklund A., Stenlund T., Steinholtz K., Ahlgren C. Take charge: Patients’ experiences during participation in a rehabilitation programme for burnout. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine. 2010; 42: 475–481.

- Franche R.L., Cullen K., Clarke J., Irvin E., Sinclair S., Frank J. Workplace-based return-to-work interventions: A systematic review of the quantitative literature. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation. 2005; 15: 607–631.

- Franche R.L., Krause N. Readiness for return to work following injury or illness: Conceptualizing the interpersonal impact of health care, workplace, and insurance factors. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation. 2002; 12: 233–256.

- Gard G., Larsson A. Focus on motivation in the work rehabilitation planning process: A qualitative study from the employer's perspective. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation. 2003; 13: 159–167.

- Gjesdal S., Bratberg E., Maeland J.G. Musculoskeletal impairments in the Norwegian working population: The prognostic role of diagnoses and socioeconomic status: A prospective study of sickness absence and transition to disability pension. Spine. 2009; 34: 1519–1525.

- Grahn B., Ekdahl C., Borgquist L. Motivation as a predictor of changes in quality of life and working ability in multidisciplinary rehabilitation. A two-year follow-up of a prospective controlled study in patients with prolonged musculoskeletal disorders. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2000; 22: 639–654.

- Harkapaa K., Jarvikoski A., Gould R. Motivational orientation of people participating in vocational rehabilitation. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation. 2014; 24: 658–659.

- Haugli L., Maeland S., Magnussen L.H. What facilitates return to work? Patients experiences 3 years after occupational rehabilitation. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation. 2011; 21: 573–581.

- Hedlund M., Landstad B.J., Wendelborg C. Challenges in disability management of long-term sick workers. International Journal of Disability Management. 2007; 2: 47–56.

- Hoefsmit N., Houkes I., Nijhuis F.J. Intervention characteristics that facilitate return to work after sickness absence: A systematic literature review. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation. 2012; 22: 462–477.

- Iles R.A., Davidson M., Taylor N.F. Psychosocial predictors of failure to return to work in non-chronic non-specific low back pain: A systematic review. Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2008; 65: 507–517.

- Ilmarinen J. Work ability—A comprehensive concept for occupational health research and prevention, Scandinavian Journal of Work. Environment & Health. 2009; 35: 1–5.

- Jakobsen K., Lillefjell M. Factors promoting a successful return to work: From an employer and employee perspective. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2014; 21: 48–57.

- Kuoppala J., Lamminpaa A. Rehabilitation and work ability: A systematic literature review. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine. 2008; 40: 796–804.

- Lagerveld S.E., Bultmann U., Franche R.L., van Dijk F.J., Vlasveld M.C., van der Feltz-Cornelis C.M., Nieuwenhuijsen K. Factors associated with work participation and work functioning in depressed workers: A systematic review. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation. 2010; 20: 275–292.

- Landstad B., Hedlund M., Wendelborg C., Brataas H. Long-term sick workers experience of professional support for re-integration back to work. Work. 2009; 32: 39–48.

- Landstad B.J., Wendelborg C., Hedlund M. Factors explaining return to work for long-term sick workers in Norway. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2009; 31: 1215–1226.

- Lederer V., Loisel P., Rivard M., Champagne F. Exploring the diversity of conceptualizations of work (dis)ability: A scoping review of published definitions. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation. 2014; 24: 242–267.

- Leplege A., Gzil F., Cammelli M., Lefeve C., Pachoud B., Ville I. Person-centredness: Conceptual and historical perspectives. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2007; 29: 1555–1565.

- Lillefjell M. Gender differences in psychosocial influence and rehabilitation outcomes for work-disabled individuals with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation. 2006; 16: 659–674.

- Loisel P., Buchbinder R., Hazard R., Keller R., Scheel I., van Tulder M., Webster B. Prevention of work disability due to musculoskeletal disorders: The challenge of implementing evidence. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation. 2005; 15: 507–524.

- Lydell M., Hildingh C., Mansson J., Marklund B., Grahn B. Thoughts and feelings of future working life as a predictor of return to work: A combined qualitative and quantitative study of sick-listed persons with musculoskeletal disorders. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2011; 33: 1262–1271.

- MacEachen E., Clarke J., Franche R.L., Irvin E. Systematic review of the qualitative literature on return to work after injury, Scandinavian Journal of Work. Environment & Health. 2006; 32: 257–269.

- Malterud K. Systematic text condensation: A strategy for qualitative analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health. 2012; 40: 795–805.

- Mussener U., Svensson T., Soderberg E., Alexanderson K. Encouraging encounters: Sick-listed persons’ experiences of interactions with rehabilitation professionals. Social Work in Health Care. 2008; 46: 71–87.

- Nilsson S., Ekberg K. Employability and work ability: Returning to the labour market after long-term absence. Work. 2013; 44: 449–457.

- Noordik E., Nieuwenhuijsen K., Varekamp I., van der Klink J.J., van Dijk F.J. Exploring the return-to-work process for workers partially returned to work and partially on long-term sick leave due to common mental disorders: A qualitative study. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2011; 33: 1625–1635.

- Nordenfelt L. The concept of work ability. 2008; Brussels: P.I.E. Peter Lang.

- Norlund A., Ropponen A., Alexanderson K. Multidisciplinary interventions: Review of studies of return to work after rehabilitation for low back pain. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine. 2009; 41: 115–121.

- Norlund S., Fjellman-Wiklund A., Nordin M., Stenlund T., Ahlgren C. Personal resources and support when regaining the ability to work: An interview study with exhaustion disorder patients. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation. 2013; 23: 270–279.

- OECD. Sickness, disability and work: Breaking the barrier. A synthesis of findings across OECD countries. 2010; Paris: OECD.

- Oesch P., Kool J., Hagen K.B., Bachmann S. Effectiveness of exercise on work disability in patients with non-acute non-specific low back pain: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine. 2010; 42: 193–205.

- Oyeflaten I., Lie S.A., Ihlebaek C.M., Eriksen H.R. Prognostic factors for return to work, sickness benefits, and transitions between these states: A 4-year follow-up after work-related rehabilitation. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation. 2014; 24: 199–212.

- Palmer K.T., Harris E.C., Linaker C., Barker M., Lawrence W., Cooper C., Coggon D. Effectiveness of community- and workplace-based interventions to manage musculoskeletal-related sickness absence and job loss: A systematic review. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2012; 51: 230–242.

- Pransky G., Benjamin K., Hill-Fotouhi C., Himmelstein J., Fletcher K.E., Katz J.N., Johnson W.G. Outcomes in work-related upper extremity and low back injuries: Results of a retrospective study. American Journal of Industrial Medicine. 2000; 37: 400–409.

- Pransky G., Gatchel R., Linton S.J., Loisel P. Improving return to work research. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation. 2005; 15: 453–457.

- Reiso H., Nygard J.F., Brage S., Gulbrandsen P., Tellnes G. Work ability and duration of certified sickness absence. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health. 2001; 29: 218–225.

- Schandelmaier S., Ebrahim S., Burkhardt S.C., de Boer W.E., Zumbrunn T., Guyatt G.H., Kunz R. Return to work coordination programmes for work disability: A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. PLoS.One. 2012; 7: e49760.

- Seing I., Stahl C., Nordenfelt L., Bulow P., Ekberg K. Policy and practice of work ability: A negotiation of responsibility in organizing return to work. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation. 2012; 22: 553–564.

- Selander J., Marnetoft S.U., Asell M. Predictors for successful vocational rehabilitation for clients with back pain problems. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2007; 29: 215–220.

- Selander J., Marnetoft S.U., Bergroth A., Ekholm J. Return to work following vocational rehabilitation for neck, back and shoulder problems: Risk factors reviewed. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2002; 24: 704–712.

- Shaw W., Hong Q.N., Pransky G., Loisel P. A literature review describing the role of return-to-work coordinators in trial programs and interventions designed to prevent workplace disability. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation. 2008; 18: 2–15.

- Soderberg S., Jumisko E., Gard G. Clients’ experiences of a work rehabilitation process. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2004; 26: 419–424.

- Stahl C., Svensson T., Petersson G., Ekberg K. A matter of trust? A study of coordination of Swedish stakeholders in return-to-work. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation. 2010; 20: 299–310.

- The National Insurance Act. The Norwegian Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs. [Lov om folketrygd]. 1997. Retrieved October 1, 2014 from http://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/1997-02-28-19.

- The Work Environment Act. The Norwegian Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs. [Lov om arbeidsmiljø, arbeidstid og stillingsvern mv.]. 2005. Retrieved October 1, 2014 from http://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/2005-06-17-62.

- Tjulin A., MacEachen E., Ekberg K. Exploring workplace actors experiences of the social organization of return-to-work. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation. 2010; 20: 311–321.

- van Oostrom S.H., Driessen M.T., de Vet H.C., Franche R.L., Schonstein E., Loisel P., … Anema J.R. Workplace interventions for preventing work disability. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2009 2 006955.

- Waddell G. Preventing incapacity in people with musculoskeletal disorders. British Medical Bulletin. 2006; 77–78: 55–69.

- Waddell G., Burton K. Is work good for your health and well-being?. 2006; London: The Stationary Office.

- Winde L.D., Alexanderson K., Carlsen B., Kjeldgård L., Wilteus A.L., Gjesdal S. General practitioners’ experiences with sickness certification: A comparison of survey data from Sweden and Norway. BMC Family Practice. 2012; 13: 10.

- Young A.E., Roessler R.T., Wasiak R., McPherson K.M., van Poppel M.N., Anema J.R. A developmental conceptualization of return to work. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation. 2005a; 15: 557–568.

- Young A.E., Wasiak R., Roessler R.T., McPherson K.M., Anema J.R., van Poppel M.N. Return-to-work outcomes following work disability: Stakeholder motivations, interests and concerns. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation. 2005b; 15: 543–556.