Abstract

This paper looks at the implications of user fees for women’s utilization of health care services, based on selected studies in Africa. Lack of access to resources and inequitable decision-making power mean that when poor women face out-of-pocket costs such as user fees when seeking health care, the cost of care may become out of reach. Even though many poor women may be exempt from fees, there is little incentive for providers to apply exemptions, as they too are constrained by restrictive economic and health service conditions. If user fees and other out-of-pocket costs are to be retained in resource-poor settings, there is a need to demonstrate how they can be successfully and equitably implemented. The lack of hard evidence on the impact of user fees on women’s health outcomes and reproductive health service utilization reminds us of the urgent need to examine how women cope with health care costs and what trade-offs they make in order to pay for health care. Such studies need to collect gender-disaggregated data in relation to women’s health service utilization and in relation to the range of reproductive health services, taking into account not only out-of-pocket fees charged by public health providers but also by private and traditional providers.

Résumé

Cet article examine l’influence de la rétribution des services de santé sur l’utilisation de ces services par les femmes, avec des études choisies en Afrique. Le manque d’accès aux ressources et le pouvoir de décision inéquitable font que si les femmes pauvres doivent payer les soins de leur poche, le coût de la santé risque de devenir inabordable. Beaucoup de femmes pauvres peuvent être exonérées, mais les prestataires de services hésitent à appliquer ces avantages, car ils sont également limités par des conditions économiques et de service restrictives. Pour maintenir la rétribution des services par les usagers dans des environnements pauvres en ressources, il faut montrer comment ces mesures peuvent être appliquées équitablement et avec succès. Le manque d’information sur l’impact de la rétribution sur la santé des femmes et l’utilisation des services de santé génésique rappelle qu’il faut étudier comment les femmes supportent le coût de la santé et à quelles dépenses elles renoncent pour y parvenir. Ces études recueilleront des données ventilées par sexe sur l’utilisation des services par les femmes et sur la gamme de services de santé génésique, en tenant compte des coûts versés par les usagers aux prestataires publics, mais aussi privés et traditionnels.

Resumen

Este trabajo utiliza unos estudios realizados en África sobre las implicaciones del costo de servicios de salud para las mujeres. Estos costos pueden ser inalcanzables para las mujeres pobres debido a su falta de acceso a los recursos y a la desigualdad en el poder de tomar decisiones. Aunque muchas mujeres pobres estén exoneradas del pago, los proveedores raramente aplican las excepciones, ya que ellos también están constreñidos por las condiciones económicas y por los servicios mismos. Si los usuarios deben pagar los honorarios y otros costos, entonces es necesario demostrar cómo se pueden implementar equitativa y exitosamente. La falta de datos sólidos acerca del impacto del pago de honorarios sobre la salud de la mujer y su utilización de los servicios de la salud reproductiva nos indica que urge examinar cómo cubren las mujeres el costo de la atención en salud y que sacrificios hacen para poder pagar. Se precisan estudios que recogen datos separados por género en relación a la utilización de los servicios de salud por las mujeres y en relación a la oferta de servicios de salud reproductiva, tomando en cuenta los honorarios cobrados por los proveedores de salud pública y también por los proveedores privados y tradicionales.

In the current environment of shrinking global and domestic resources for health care, there is an overwhelming pressure to achieve financial sustainability in the health sectors of developing countries Citation[1]. Within this context, there seems to be increasing acceptance of the view that individuals need to contribute to some of the costs of public health care through charges such as user fees and other cost-recovery mechanisms. The large body of empirical evidence on the impact of user fees on utilization of health care services, however, suggests that user fees are regressive and inequitable, in that poor people pay a greater proportion of their incomes out of pocket for health care than those who are better off, unless there are effective exemptions in place to protect them and the quality of health care is simultaneously improved Citation[1]Citation[2]Citation[3]. Hence, contemporary debates around user fees have shifted beyond arguing for the mere introduction of user fees, to a focus on how to target exemptions so that they can act as effective safety nets for the poor and on alternative mechanisms of cost recovery that are not regressive Citation[4].

Neglected in much of the literature and the evolving debates, however, are the ways in which user fees are regressive as regards gender equity. The overall lack of gender-disaggregated data in the studies on user fees exemplifies this problem Citation[5]. The purpose of this paper, through a review of the more recent literature on user fees in Africa, is to raise some of the gender considerations arising from user fees and the assumptions around their introduction and implementation. A gender-based analysis of user fees should look at two aspects of the problem: first, the differential impact of user fees on utilization of health care between men and women and second, how user fees affect women’s utilization of health care for themselves Citation[5]. There is a paucity of data on the first question. This paper will focus on the implications of user fees for women’s utilization of health care services.

Women’s poverty is critically linked to women’s health needs and ability to use health services. Of the 1.3 billion poorest people in the world, 70% are women Citation[6]. Within households, women bear an inequitable burden of providing food, health and shelter for themselves and their families. Women also face social and physical barriers to accessing health care services, especially due to their disproportionate need for reproductive health care.

For women living in poverty, user fees have direct and obvious links with the ability to pay out of pocket for health care. Where women are struggling to make ends meet, they have little to save for contingencies, which include health and sickness. Women may make trade-offs in not seeking health care in order to purchase food or fuel, or they may seek traditional health care that does not address their health needs adequately Citation[7]. Further, women in subsistence economies may not have access to cash income or men may have control over women’s earnings Citation[6].

This paper reviews some of the literature on user fees and their impact on health care utilization in Africa from the mid-1990s, the same time period when issues of gender equity started to influence health policies and debates, following the International Conference on Population and Development in 1994. Seminal articles from the late 1980s and early 1990s that formed the initial work on user fees have been included for a historical perspective and to shed light on contemporary debates.

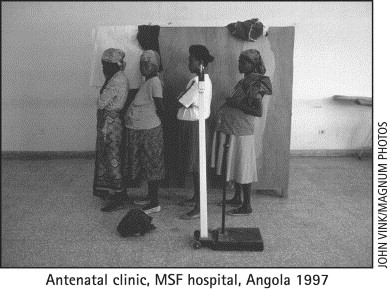

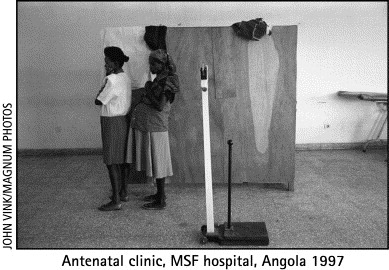

In addition to review articles, most of these papers examine the impact of user fees on outcomes such as drug supply, quality of care and utilization of health services in one or more countries. More recent studies use community-based surveys and other qualitative methods to analyze people’s ability to pay, their experience of exemptions and how they cope with out-of-pocket costs. Few of the studies reviewed have looked at women’s health outcomes or at patterns of utilization of antenatal care, maternity care or family planning services in relation to the introduction of user fees.

Context of user fees

User fees are charges to the individual for health care at the time of utilization. Unlike other forms of health care financing, such as pre-payment schemes or insurance, the timing of payment coincides with the need for health care Citation[4]. Of all cost recovery mechanisms, user fees have been viewed as the measure most amenable to immediate application and the one that would pave the way for other mechanisms Citation[1]. Fees are considered complementary to tax-based financing for government health services, including in countries that previously provided free public health care Citation[4]Citation[7].

User fees have been implemented in many countries since the 1980s. Their introduction can partly be traced to the structural adjustment policies that were initiated when many developing countries underwent severe economic recession due to the first “oil crisis”. The International Monetary Fund and World Bank loaned money to those with distressed economies with stringent conditions attached. These typically involved a cut in government expenditure for social sectors, e.g. in the health sector the privatization of government-provided health services, and cost recovery strategies such as user fees, health insurance and pre-payment schemes Citation[4]Citation[8]. It was also intended that they would contribute to increasing the resources available to governments to expand and upgrade their network of health care services, as well as reduce inefficiencies in health care delivery by decreasing frivolous use of services and improve the quality of services, e.g. through a more rational referral system and better availability of drugs and medical supplies. Another intended benefit was enhanced accountability to individuals and communities Citation[3].

The World Bank explicitly recommended user fees in its strategy “Agenda for Reform” in 1987 Citation[4]. User fees implemented through health sector reforms and specifically health financing reforms aimed to improve efficiency and equity in health systems Citation[8]. User fees have also been implemented as part of the Bamako Initiative in 1988, following the commitment to “Health for All by 2000” undertaken at Alma Ata. In contrast to the top-down user-fee model initiated through structural adjustment, the goals of the Bamako Initiative were to raise and control revenues at the primary health level through community-based activities and the development of community management capacities Citation[7].

Recent reviews from Ghana, Swaziland, Zaire and Uganda, suggest that the introduction of user fees is often followed by a subsequent decrease in service utilization Citation[9]Citation[10]Citation[11]. The magnitude of this drop in utilization is often greater and occurs over a longer period for the poorer population Citation[7]. A study from Swaziland suggests that those most affected by fee increase are patients who are either low income, those needing to make multiple visits or those who decide their ailment is not serious enough to justify costs Citation[11]. The same study noted that attendance for STDs dropped at government facilities without an accompanying increase at mission hospitals Citation[11]. In Kenya, as well, the introduction of user fees (amounting to half a day of pay for a poor person) in government outpatient health facilities led to a dramatic reduction in utilization of STD services by both men and women, but at significantly greater rates for women. Before the introduction of user fees, there were fewer women than men attending. Nine months after their introduction, the fees were revoked, and women’s utilization rose to a greater level than the pre-fees level Citation[12].

The studies that look at specific women’s health care services validate that they too are price sensitive and that utilization has tended to drop when fees have been charged. Evidence from several African countries suggests that use of maternal health care services is affected when fees are introduced or revoked. Decline in prenatal use was noted in Zimbabwe in the early 1990s when user fees were strongly enforced Citation[8]. A study of the impact of user fees for antenatal care in government hospitals in three districts of Tanzania showed a 53.4% decline in utilization after fees were introduced Citation[13]. A study from Nigeria reports that when user fees were introduced, maternal deaths in the Zaria region rose by 56% along with a decline of 46% in the number of deliveries in the main hospital Citation[14]. In contrast, in South Africa antenatal care attendance improved after charges were revoked Citation[15].

Challenging the assumptions of user fees

The rationale and support for user fees rests on several assumptions:

| • | fees are nominal and the majority of the poor are able to pay them; | ||||

| • | where the poor or indigent are unable to pay, exemptions can be put in place to protect them; | ||||

| • | there are tangible benefits to users as revenue from user fees can help enhance the quality of health services. | ||||

A review of the literature suggests that the reality of user fees may be different. A review of cost recovery policies in sub-Saharan Africa shows a narrow emphasis on raising revenue without explicit equity objectives Citation[3]. Several studies show user fees are often not accompanied by improvements in quality or availability of drugs Citation[9]Citation[16]Citation[17]. Even in terms of raising revenue, studies have found that the recovery rates are often not more than 5–10% of recurrent costs (although they could cover a higher proportion of non-recurrent costs) Citation[7]. The net revenue raised is insufficient to address the existing quality and weaknesses in coverage of the health system as a whole Citation[3]. The low revenue base in itself is an argument against implementing user fees because the potential revenue gained by collecting fees for essential services in resource poor settings is often miniscule given the high administrative costs involved in collecting and disbursing them Citation[7].

However, recent studies suggest that covering even a small proportion of overall revenue is a contribution to an under-funded health sector, even though it may not be enough to bring improvements in quality or compensate health workers for loss of revenue due to exemptions Citation[18]. If fees are retained at the local level, the income can be used to enhance staff salaries through bonuses Citation[19]. This becomes especially relevant in the face of increased demoralization and out-migration of health staff due to the low level and even non-payment of salaries, a reality faced by many of the African countries undergoing health sector reforms Citation[1]Citation[7]Citation[16]. The issue of revenue retention and how it can be used to improve quality of services is a critical one, and relevant also within the context of exemptions Citation[20].

Re-defining ability to pay

Proponents of user fees argue that the fees are often small, amounting on average to half a day’s wages in many countries, and therefore accommodate poor households’ ability to pay Citation[7]. The fact that poor people do pay for health care when they go to traditional and private facilities is said to signify their willingness and ability to pay for health care. Russell Citation[21] critiques this traditional view and counters that the entire consumption profile of a household needs to be examined. People are unable to pay when utilization is restrained by financial necessities or when consumption of other essential commodities, such as food, water or education, fall below minimum needs. He calls for a longer-term perspective and defines health care as affordable only when consumption of or investment in essential commodities does not fall below levels that may affect either future health, earning capacity or future expenditures.

At the individual level, the ability of the poor to pay user fees is not only affected by their income but also by the prices of other goods in their basket of commodities and services. For example, an increase in food prices impinges on the household income available to pay for health services Citation[8]. Therefore, if the poor are required to pay for health care, they may be forced to make trade-offs with consumption of other essentials such as food or education Citation[16]. Or families may take out loans to pay for health needs in more acute situations Citation[8]Citation[22].

When faced with health expenses they cannot immediately meet, households use resources other than cash, such as the sale of land and other assets, the exchange of labour or food for cash, loans, claims on kin, or use of common property Citation[21]. Sale of livestock has been reported as a common strategy to meet health care expenses in a study in Burkina Faso Citation[22]. Over time and with periodic or chronic illnesses, a household’s resources can be eroded, which further affects their overall ability to pay Citation[21]Citation[22].

In talking about ability to pay it is important to factor in other costs over and above user fees that people might encounter in seeking health care. User fees are often not isolated, but additive to other out-of-pocket costs that people incur in seeking health care. For example, the opportunity costs of time spent in travel and in queuing, amounting to loss of a day’s wage, can be a significant aspect of the total costs of using medical services. Where public services are distant, user fees add another layer of costs to the costs of transportation Citation[21].

Exploring women’s ability to pay for health care

Literature on women’s health-seeking behaviour suggests that women’s ability to pay needs to be redefined from a gender perspective, taking into account their access to and control over resources and decision-making about health. Further, their willingness to pay is determined by the social costs of health care, including factors such as perceived morbidity and severity of illness and perceived quality of care Citation[23]. A qualitative study from Ghana reports that within poor households, women generally find it more difficult to pay for health care, but especially widows and unmarried women with children Citation[16].

Furthermore, because illness necessitates reallocation of time and resources within a household, a person’s position in the household will determine the reallocations made towards that person’s health care Citation[22]Citation[23]. In a qualitative household study in Uganda on coping strategies to pay for health care, women were found to have the primary responsibility towards their own and their children’s health, while it is frequently men who have cash available, particularly that derived from the sale of cash crops Citation[24]. The burden of taking care of the sick falls on women, which not only increases their workload but also makes less time available for earning an income, creating a vicious cycle.

To those dependent on agricultural income, access to cash is seasonal and restricts ability to pay for costs like health care because of the lack of predictability of expenditures and lack of safety nets or savings Citation[23]. A 1999 study in Uganda by Lucas and Nuwagaba suggests that availability of cash at the community level is high only for four months of the year. In addition, women often do not control earnings from cash crops even if they do the work on the farms. Their ability to access cash at any time of the year is thus restricted. If a woman has a condition that needs regular care or treatment, she may not be able to afford this over a long period even if she can pay fees at any one point in time. Thus, several studies report that individuals opt for traditional care because payment can be on credit Citation[9]Citation[16]Citation[17]Citation[23].

Women’s ability to pay is not only affected by user fees but by other informal or hidden costs in addition to fees. Several studies have reported other out-of-pocket costs for maternity care, such as gloves, syringes and drugs Citation[25]Citation[26]. A study of maternity care in Uganda reports that these costs were significantly higher than the user fees (from the fee of 3,000 the actual costs could go up to 15,000 shillings) and included gloves, injections, paraffin and polythene bags for an attended delivery. If the expectant mother cannot cover these costs, she is likely to get poor attention even if she has paid the user fee Citation[26].

The effective decision for the very poor may be not to seek care at all, or to go to traditional healers or resort to partial treatment Citation[9]Citation[16]Citation[21]Citation[23]Citation[26]Citation[27]. However, there are likely to be further costs if care is sought only after an illness is severe, or if ineffectual treatment has been used or treatment is not completed.

Examining the practice of exemptions

In several countries, such as Zambia, Ghana and Tanzania, antenatal care and family planning services are exempt from user fees and often there are no fees for pregnant women, children under five or the very poor Citation[7]Citation[19]. In high fertility settings, exemptions for these categories of women would constitute the majority of women who seek health care to begin with. Patients with severe health conditions (e.g. AIDS, tuberculosis or other communicable diseases) are also treated free of charge irrespective of the ability to pay, due to public health considerations Citation[19]. Taken together, these criteria constitute a large proportion of health care seekers in a poor African community, especially women, defeating the primary motivation for applying user fees Citation[7].

The inconsistency in the objectives of protecting the poor on one hand, and generating revenue from user fees to pay for health services on the other, constitutes a dilemma for health managers entrusted with the responsibility of executing exemptions Citation[19]. The fact that women are affected by the inconsistencies and poor execution of exemption policies is stating the obvious when the exemption policies themselves recognize women as the main intended beneficiaries.

Women, constituting a significant proportion of potential beneficiaries of exemptions, often do not know that these are available. In many African settings women are semi-literate and have to rely on verbal information Citation[19]. There is often no systematic or formal process for them to find out about exemptions; most can obtain information informally from health care staff, friends or relatives.

In Tanzania, while maternal health and family planning services are exempt, other areas of women’s reproductive health (e.g. gynaecology, infertility, abortion or treatment for infectious diseases) are not exempt. Additionally, in some regions of the country and for some specific methods of family planning e.g. Norplant and voluntary sterilization, the only available services are offered at NGO-run clinics where women have to pay fees for these services Citation[28]. Exemptions may not have a significant impact on utilization if the public facilities do not offer those health services and women still need to pay for them elsewhere. Or women may need to pay for services for which the social costs are higher (such as treatment seeking for STDs) than those services for which they are exempt, such as maternal care. The consequences can be serious both for a woman’s health and from a public health standpoint.

Several studies from Ghana, Uganda, Kenya and Zimbabwe report the misuse of exemptions in clinic settings Citation[16]Citation[19]Citation[29]. Studies from Ghana, Uganda and Kenya report that records and monitoring of the exemptions systems were nearly non-existent Citation[16]Citation[19]Citation[29]Citation[30]. The leakages of exemptions to the non-poor and lack of incentives to exercise exemptions, given the low salary base of health workers, constitute some of the concerns with the practice Citation[19]. A comprehensive study of six countries, including Kenya, Ghana and Zimbabwe, suggests discretionary waiving of fees based on client characteristics and relations, or discretionary application of fees where exemptions should apply, based on the motivations and circumstances of providers Citation[19]. In Zambia providers reported discretionary application of fees to STD patients who are actually exempt because “they have called it upon themselves” Citation[31]. In the same study, providers also reported that STD patients could be denied drugs that had other competing uses because of acute drug shortages in the country. Overall, the evidence suggests that exemptions are vulnerable to subjectivity and distortion.

Discussion

The empirical evidence for the effects of user fees on women’s health outcomes is sparse. Most studies have tended to focus on the poor, but with no disaggregation by sex. Recognizing these limitations, this paper highlights several key points that are relevant to a gender-based analysis of user fees. Some of these points hold true for all vulnerable groups, as well as for those who are chronically ill. But the fact that women are often more marginalized by the social costs of seeking health care, as well as by their specific needs for reproductive health care, necessitates a more visible recognition of the problems they face if they have to pay out of pocket for health care.

The fact that user fees may be low or nominal does not preclude other costs that women experience over and above user fees, which together can add up to amounts beyond their means. The trade-offs that women may make in order to pay for health care can lead to debt, use of ineffectual treatments or neglect of their health and other needs.

There is little incentive for providers to apply exemptions, as they too are constrained by restrictive economic and health service conditions. Exemptions for those who cannot afford to pay as currently conceived often seem not to be applied, or are abused or applied inequitably. If user fees and other out-of-pocket costs are retained in resource-poor settings, then there is a need for research to demonstrate whether and how user fees can be successfully and equitably implemented.

To date, even in recent studies, there is little evidence that user fees work in terms of their ability to recover a sufficient proportion of recurrent costs to justify their continuation. The onus for future research is to demonstrate whether and how user fees can improve the resources available in primary health care settings without reducing utilization or hurting those who are poor and vulnerable. Only when there is evidence that user fees can be effective should they be implemented on a broader scale. Such studies need to collect gender-disaggregated data in relation to health services generally and also in relation to reproductive health services. This means not only antenatal care but also deliveries, family planning, abortions, treatment of STDs and tertiary-level gynaecological care, taking into account not only user fees and other out-of-pocket fees charged by public health providers but those of private and traditional providers as well. Issues around women’s ability to pay are pertinent to thinking about other methods of cost recovery, including pre-payment schemes and health insurance mechanisms.

Lastly, health economists need to give more credence to the reality of the daily lives of poor women in proposals for health sector policies that will impact women’s utilization of health services, including reproductive health services. This underscores the need to frame the right questions, such as how women cope with user and other out-of-pocket fees in relation to different health needs and services. The lack of hard evidence on the impact of user fees on women’s health outcomes or service utilization reminds us of the urgent need to examine the budgetary implications of user fees at the household level, what the health consequences are of delays in health care seeking or recourse to affordable but ineffectual care, and what trade-offs they make in order to pay for health care. This is imperative to mitigate the negative effects of current health economics policies on the health of poor women.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank my colleagues Anna Benton, Avni Amin and Jodi Jacobson from CHANGE for their support and comments on this paper.

References

- B. McPake. User charges for health services in developing countries: a review of the economic literature. Social Science and Medicine. 36(11): 1993; 1397–1405.

- B. Stanton, J. Clemens. User fees for health care in developing countries: a case study of Bangladesh. Social Science and Medicine. 29(10): 1989; 1199–1205.

- S. Russell, L. Gilson. User fee policies to promote health service access for the poor: a wolf in sheep’s clothing?. International Journal of Health Services. 27(2): 1997; 359–379.

- Arhin-Tenkorang D. Mobilizing Resources for Health: The Case for User Fees Revisited. Working Paper No. 81. Cambridge MA: Center for International Development, 2001

- H. Standing. Gender and equity in health sector reform programmes: a review. Health Policy and Planning. 12(1): 1997; 1–18.

- W. Harcourt. Women, Health and Globalisation. 2001; Society for International Development: Rome.

- L. Gilson. The lessons of user fee experience in Africa. Health Policy and Planning. 12(4): 1997; 273–285.

- Breman A, Shelton C. Structural adjustment and health: a literature review of the debate, its role players and presented empirical evidence. CMH Working Papers Series WG6: No. 6. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2001

- S. Haddad, P. Fournier. Quality, cost and utilisation of health services in developing countries: a longitudinal study in Zaire. Social Science and Medicine. 40(6): 1995; 743–753.

- S. Bennett, L. Gilson. Health Financing: Designing and Implementing Pro-Poor Policies. 2001; DFID Health Systems Resource Centre: London.

- R. Yoder. Are people willing and able to pay for health services?. Social Science and Medicine. 29(1): 1989; 35–42.

- S. Moses, F. Manji. Impact of user fees on attendance at a referral centre for sexually transmitted diseases in Kenya. Lancet. 340: 1992; 463–466.

- A.K. Hussein, P.G.M. Mujinja. Impact of user charges on government health facilities in Tanzania. East African Medical Journal. 74(12): 1997; 751–757.

- C.C. Ekwempu, D. Maine. Structural adjustment and health in Africa. Lancet. 336: 1990; 56–57.

- H. Schneider, L. Gilson. The impact of free maternal health care in South Africa. M. Berer, T.K.S. Ravindran. Safe Motherhood Initiatives: Critical Issues. 2000; Reproductive Health Matters: London.

- C. Waddington, K.A. Enyimayew. A price to pay. Part 2: The impact of user charges in the Volta Region of Ghana. International Journal of Health Planning and Management. 5: 1990; 287–312.

- B. Abel-Smith, P. Rawall. Can the poor afford “free” health services? A case study of Tanzania. Health Policy and Planning. 7(4): 1992; 329–341.

- Wouters A, Adeyi O, Marrow R. Quality of health care and its role in cost recovery with a focus on empirical findings about willingness to pay for quality improvements. HFS Major Applied Research Paper No. 8. Bethesda MD: Abt Associates, 1993

- R. Bitran, U. Giedion. User fees for health care: Waivers, exemptions and implementation issues. 2002; World Bank: Washington DC. (draft).

- Vogel R. Cost recovery in the health care sector: Selected country studies in West Africa. World Bank Technical Paper No. 62. Washington DC: World Bank, 1982

- S. Russell. Ability to pay for health care: concepts and evidence. Health Policy and Planning. 11(3): 1996; 219–237.

- R. Sauerborn, A. Adams, M. Hien. Household strategies to cope with the economic costs of illness. Social Science and Medicine. 43(3): 1996; 291–301.

- S. Muela, A. Mushi, J. Ribera. The paradox of the cost and affordability of traditional and government health services in Tanzania. Health Policy and Planning. 15(3): 2000; 296–302.

- Lucas H, Nuwagaba A. Household coping strategies in response to the introduction of user charges for social service: a case study on health in Uganda. IDS Working Paper 86. Brighton: Institute for Development Studies, 1999

- S. Nahar, A. Costello. The hidden cost of ‘free’ maternity care in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Health Policy and Planning. 13(4): 1998; 417–422.

- Konde-Lule J, Okello D. User Fees in Government Health Units in Uganda: Implementation, Impact, and Scope. PHR/SAR Paper No. 2. Bethesda MD: Abt Associates, 1998

- J. Litvack, C. Bodart. User fees plus quality equals improved access to health care: results of a field experiment in Cameroon. Social Science and Medicine. 37(3): 1993; 369–383.

- Richey L. Obstacles to Quality of Care in Family Planning and Reproductive Health Services in Tanzania. Working Paper 2. Measure Evaluation Project: University of North Carolina (Chapel Hill), 1998

- B. McPake, S.D. Asiimwe. Informal economic activities of public health workers in Uganda: implications for quality and accessibility of care. Social Science and Medicine. 49: 1999; 849–865.

- Newbrander W, Collins D. Equity in the provision of health care: ensuring access to the poor to services under user fee systems. Paper presented at East African Senior Policy Seminar on Sustainable Health Care Financing, Nairobi, 1997

- Nanda P. Health Sector Reforms in Zambia: Implications for Reproductive Health and Rights. CHANGE Working Paper. Takoma Park MD: Center for Health and Gender Equity, 2000