Abstract

This paper discusses health sector reforms and what they have meant for sexual and reproductive health advocacy in low-income countries. Beginning in the late 1980s, it outlines the main macro-economic shifts and policy trends which affect countries dependent on external aid and the main health sector reforms taking place. It then considers the implications of successive macro-economic and reform agendas for reproductive and sexual health advocacy. International debate today is focused on the conditions necessary for socio-economic development and the role of governments in these, and how to improve the performance of health sector bureaucracies and delivery systems. A critical challenge is how to re-negotiate the policy and financial space for sexual and reproductive health services within national health systems and at international level. Advocacy for sexual and reproductive health has to tread the line between a vision of reproductive health for all and action on priority conditions, which means articulating an informed view on needs and priorities. In pressing for greater funding for reproductive health, advocates need to find an appropriate balance between concern with health systems strengthening and service delivery and programmes, and create alliances with progressive health sector reformers.

Résumé

Cet article décrit les réformes du secteur sanitaire et leurs conséquences sur le plaidoyer pour la santé génésique dans les pays á faibles revenus. Il souligne les réorientations économiques et les tendances politiques touchant les pays dépendants de l’aide extérieure et les principales réformes qui s’y déroulent depuis la fin des années 80. Puis il étudie les conséquences des mesures macro-économiques et des réformes successives sur le plaidoyer. Le débat international est aujourd’hui centré sur les conditions du développement socio-économique et le rôle des gouvernements dans celles-ci, et sur les moyens de relever les performances des administrations du secteur sanitaire et des systèmes de services. Il importe de renégocier l’espace politique et financier pour les services de santé génésique aux niveaux national et international. Jusqu’á récemment, les réformes du secteur sanitaire et le plaidoyer pour la santé génésique suivaient des voies parallèles, sans beaucoup de communication. Le plaidoyer doit concilier une vision de la santé génésique pour tous et l’action sur les conditions prioritaires, en comprenant les besoins et les priorités. Lorsqu’ils demandent d’accroı̂tre le financement de la santé génésique, les responsables du plaidoyer doivent trouver un juste équilibre entre leurs préoccupations pour les systèmes de santé et les programmes et la prestation de services, et créer des alliances avec des réformateurs progressistes du secteur de la santé.

Resumen

Este artı́culo trata de las reformas del sector salud y su significado para la promoción y defensa de la salud sexual y reproductiva en los paı́ses de bajos ingresos. Traza los cambios macroeconómicos principales y las tendencias polı́ticas que afectan los paı́ses que dependen de la ayuda externa desde los finales de los ochenta, además de las principales reformas del sector salud ya en curso. El debate internacional de hoy estȧ enfocado en las condiciones necesarias para el desarrollo socio-económico y el papel de los gobiernos en ellas, y en cómo mejorar el desempeño de las burocracias y los servicios del sector salud. Un desafı́o crı́tico es cómo re-negociar el cuadro polı́tico y financiero correspondiente a los servicios de salud sexual y reproductiva dentro del sector salud, tanto a nivel nacional como internacional. La promoción y defensa de la salud sexual y reproductiva tiene que seguir una lı́nea entre una visión de la salud reproductiva para todos, por un lado, y el tratamiento de condiciones prioritarias, por otro, el cual significa articular un punto de vista informado acerca de las necesidades y prioridades. Quienes insisten en incrementar el financiamiento para la salud reproductiva deben encontrar un equilibrio apropiado entre su interés en fortalecer los sistemas de salud, y la creación de alianzas con reformadores del sector salud progresistas.

Health sector reforms have been taking place in many countries over the last decade or more. Whilst not necessarily driven by the same economic, political and social forces, there are nevertheless some common themes to the international health sector reform agenda, which stem partly from the dominance of multilateral and bilateral funding agencies in setting the terms of the debate in relation to macro-economic policy in developing countries.

This overview focuses mainly on the experience of low-income countries in Asia and sub-Saharan Africa (those with gross national income per capita below $755). These countries are the most heavily dependent on external assistance and their health sector reform programmes show a corresponding convergence. However, some of this experience is also shared by middle-income countries, particularly the transition economies of the former Communist blocs in central and east Asia, which are less aid dependent but in which similar stresses have emerged within the health sector.

In these countries, public sector services have deteriorated as costs have risen and investment has fallen short of need. This has resulted in a flight by users to alternative forms of provision, often within an unregulated market for services, together with a significant rise in the proportion of out-of-pocket expenditure by households. Governments generally are struggling to develop financing mechanisms in contexts of severe income inequality and low access and utilisation of services by the poor. Health services in many countries are seriously overburdened by diseases such as AIDS and are also facing increasing burdens from ageing populations and a rise in non-communicable diseases. These all require policy responses. Some of these factors contributed to a broader technical consensus on health sector reform which began to be exported around the world from the late 1980s, drawing particularly on the reform experiences of the United States and Britain Citation[1]Citation[2].

This overview addresses three main questions: What was the macro-economic and policy environment against which the reforms were taking place? What health sector reforms and related initiatives were being proposed or tried? What were the implications for sexual and reproductive health advocacy?

The chronology below does not imply that the reforms themselves have been taking place within such clearly delineated periods. The reform agenda is still a vibrant one and is being modified in light of the changing policy and macro-economic environment.

1980s to mid-1990s

Macro-economic and policy environment

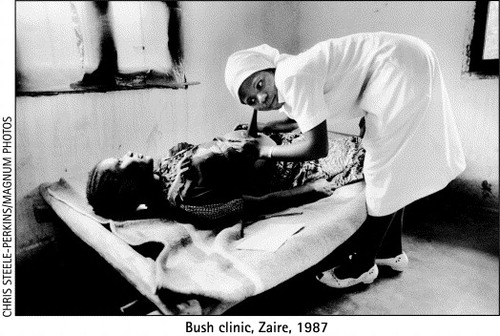

The 1980s was a decade of economic crisis in many low-income countries, particularly those of sub-Saharan Africa. Declining commodity prices, collapsing fiscal regimes and structural adjustment programmes took their toll on public investment and expenditure, with severe effects on health sectors. Public sector health facilities at all levels fell into chronic disrepair, with essential equipment missing or broken and drug and surgical supplies erratic. Service quality deteriorated. Many facilities lacked health staff as wages fell and were often irregularly paid. Informal payments by patients to staff became common as providers developed their own livelihood strategies to compensate Citation[3].

Supervisory systems lapsed and referral chains from primary to tertiary levels ceased to function properly. Hospitals increasingly levied charges for items such as drugs and surgical supplies and relied on relatives for basic nursing care. An unregulated market of providers (including “moonlighting” government employees) emerged with few or no checks on competence. The costs of health care, particularly for the poor, rose and have continued rising. There was an accelerated flight to the private sector, and declining utilisation of public services. There was also an increasing trend towards out-of-pocket expenditure and self-treatment Citation[4]Citation[5]Citation[6]. Health sector reforms during this period were an attempt to respond to the serious challenges posed by collapsing health service delivery in many poor countries Citation[7].

Health sector reform responses

This period saw the rise of what has become the mainstream health sector reform agenda, driven strongly by the World Bank, World Health Organization and a number of bilateral aid agencies. The reforms were particularly influenced by management reforms in the US and UK health systems and were concerned with redefining the relationships between the state, service providers, users and other health-related organisations, such as hospital boards and private sector providers of goods and services Citation[4].

Reforms particularly focused on improving the functioning of national Ministries of Health through more efficient financial and human resource management Citation[1]. Financing reforms advocated reduced reliance on public financing and greater emphasis on mixed public and private mechanisms to improve cost control and increase cost recovery. These included user charges, pre-payment schemes and insurances Citation[8]. Human resource management was linked to reform of civil service contracts and introduction of other means of performance monitoring, such as incentive-based pay structures.

In terms of improving the quality of service delivery, governments were encouraged to develop a more selective approach to primary health care by introducing packages of low-cost, selective interventions as a guaranteed minimum “basic package” of services Citation[9]. Decentralisation of health services either to lower tiers of government or to other agencies was recommended as a way of increasing accountability to local populations. There was a push to develop more and stronger contractual arrangements with private sector providers in both the non-profit and for-profit sectors. This was a response to the existing widespread use of these services. It also reflected a prevailing ideological view of the potentially greater quality and efficiency of the private sector and the virtues of using competitive contracting as a way of shaking up the public sector Citation[1]Citation[10].

There were also some important regionally-driven initiatives. One such was the Bamako Initiative by a group of African countries alarmed by the severe deterioration of their health services, which focused on improving service delivery through community-based financing of basic supplies Citation[11]. This has had mixed results. It improved the affordability of services in some countries for some of the poor but had little impact on access for very poor and marginalised groups Citation[12].

The mainstream approach led to concern from a number of directions. Some health advocates have consistently been critical of health sector reform, seeing it as deriving from a structural adjustment-led cost control and privatisation agenda Citation[13]Citation[14]. Footnote1 The agencies which were pushing reforms most strongly began to be concerned about their lack of impact on health systems functioning. It proved much more difficult to implement reforms in practice, particularly where they entailed wider structural reforms in the public sector and on matters of governance. There was also a more general concern that the slogan of “equity, efficiency and quality” was in reality a concern with privileging efficiency over equity and quality Citation[15].

There were also other concerns. A “one size fits all” approach does not take into account contextual factors, such as the nature of the political regime, which influence the outcome of reforms. As a largely technocratic exercise, health sector reform ignored important stakeholders such as civil society organisations. There was a neglect of what was happening at service delivery level. The focus was on system level change but with no associated monitoring of outcomes for health or their impact on service delivery Citation[3]Citation[17].

Implications for sexual and reproductive health advocacy

Sexual and reproductive health was almost invisible in this particular agenda. This is perhaps surprising, given the international importance of the Programme of Action of the 1994 International Conference on Population and Development, reinforced by the Platform of Action of the Beijing Women’s Conference, both of which contributed to a coherent, rights-based and comprehensive vision of reproductive health.

Three reasons largely account for this. First, there was a serious language and discourse gap between the two. The one spoke (and in many ways continues to speak) a managerial/technocratic language; the other spoke an advocacy language. The two sets of protagonists rarely interacted internationally, nationally or locally. Second, whilst health sector reform has been mainly focused on supply side interventions such as financing mechanisms and human resources management, sexual and reproductive health advocacy at a sectoral level has been concerned more with services and how they are delivered. At a broader level, the latter has emphasised the need for and pioneered approaches to improving gender inequality as a prerequisite to improved reproductive health. Third, sexual and reproductive health services tended to be seen by health sector reformers as vertical or “special interest” programmes. Health sector reformers therefore neglected them except as a bureaucratic challenge to improving supply side efficiency. For their part, sexual and reproductive health advocates did not sufficiently understood the importance of engaging with reforms at a systems level Citation[18].

Mid to late 1990s

Macro-economic and policy environment

By the mid-1990s, shifts were occurring in international financial architecture. Bilateral aid budgets continued to decline as a total proportion of international transfers to poorer countries. There was, however, an increase in the proportion of loans from multilateral agencies, particularly for sectoral expenditure such as health Citation[19], partly as a response to increasing concern over the impact of structural adjustment programmes on the social sectors of poor countries. In countries with significant donor support to the health sector, there was a move away from donor-specific project funding to what became known as sector investment programmes and sector-wide approaches (SWAps).

The argument against project-based funding was that it distorted national planning and priority setting by creating islands of better resourced programmes and services. It also created inefficiencies, as agencies funded activities often with little co-ordination of efforts. There was thus a move towards longer-term planning and financing of health and other sectors, negotiated between governments and the “pool” of aid donors and multilateral agencies Citation[1]Citation[20]. This has not meant the end of project-based funding. Much “parallel” funding continues to occur in countries with SWAps, but some concern among NGOs about loss of funding is being expressed.

In recognition of the limitations of supply-driven, technically focused reforms, this resulted in some broader thinking about health sector reforms, e.g. it produced greater attention to the needs and concerns of users and to the importance of involving a wider range of stakeholders, albeit at a rhetorical level. Some countries institutionalised mechanisms for consulting users on issues such as priority setting Citation[21]. In others, coalitions of civil society stakeholders – such as consumer groups and trade unions – developed advocacy strategies to enable them to voice users’ needs and interests Citation[22]Citation[23].

In health sectors, two accelerating trends could be seen. One was that of decentralisation in its many forms Citation[24]Citation[25]. The other was the continuing growth and use of private provisioning. This produced an associated shift in focus towards governance and accountability concerns and how market provision could be better regulated Citation[23].

Health sector reform responses

Evaluations of the impact of the first decade of health sector reforms produced concern at their relative failure in a number of countries, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, to deliver any obvious improvements to service delivery, particularly for the poor Citation[15]Citation[26]. This failure cannot all be laid at the door of the health sector. HIV/AIDS has produced an economic and social crisis in some countries which goes well beyond issues of health service delivery and has seriously affected health and social indicators Citation[27]. Wider systemic failures of governance, often linked to armed conflict, in some of the poorest parts of the world were major contributors to health system crises. However, in other countries too, widening gaps between rich and poor in health status and health care access (e.g. China and India) raised serious questions about the content and direction of reforms Citation[17]Citation[28]Citation[29].

Nonetheless, the basic ingredients of health sector reforms remained intact, but emphasising some elements rather than others. Earlier reform efforts were dominated by health service management and human resource perspectives on restructuring. The mid-1990s became the era of health economists and epidemiologists as the emphasis shifted to the assessment of priority health needs and how to meet them.

Stemming from the 1993 World Development Report Citation[9] and work at Harvard, taken up by the World Health Organization, global burden of disease analysis and associated priority setting methodologies became the recommended basis for planning and allocating health expenditure, and were adopted in a number of countries Citation[30]. These methodologies were particularly associated with the development of basic packages and selective interventions based on assessments of greatest health need and on maximum health gain per unit of expenditure. Though powerful tools, critics have contested the claimed objectivity of these measures, the decontextualised nature of the rankings used, and potential gender biases due to lack of gender disaggregated data and subsequent factoring in of gender inequalities in health Citation[31]Citation[32]Citation[33].

The finding in so many surveys over the last decade that many people, including the poor, use private or independent health providers, resulted in greater attention to ways of regulating and harnessing the private sector in service delivery. This produced experiments and initiatives in contracting out of selective services, and in the social marketing of packageable health goods and services such as condoms, contraceptives and mosquito nets Citation[34]Citation[35].

Implications for reproductive and sexual health advocacy

The political and organisational challenges of implementing the Cairo agenda became more apparent in this period. Sexual and reproductive health was a vision of what should be achieved. It proved less easy to translate into practice Citation[3]Citation[37]. Further, there remained a considerable gap between the broader concerns of women’s empowerment and gender equity and on-the-ground service delivery issues, and system-level approaches to health sector reform. For instance, there has been a very large number of micro-level initiatives and demonstration projects and a lot of good experience, particularly among NGOs, for delivering quality sexual and reproductive health services, especially to women. But there has been less experience of or capacity for scaling up or delivering the comprehensive vision of the ICPD Programme of Action. There were institutional, managerial and political reasons for this. Many programmes lacked capacity to deliver services in an integrated way or to broaden service provision beyond family planning and maternal and child health services. Managers and staff often felt threatened by integration, and donors continued to fund these services vertically, despite the rhetoric of and moves towards SWAps Citation[38]Citation[39]Citation[40]Citation[41]Citation[42]Citation[43].

There was little evidence of broader stakeholder and advocacy involvement in health sector reform initiatives and negotiations with donors. The US Agency for International Development, the largest donor in the reproductive health field, still does not participate in sector-wide approaches Citation[44]. Meanwhile, international bureaucratic interventions such as Safe Motherhood programmes and Integrated Management of Childhood Illnesses (IMCI) have formed further parallel tracks, often with separate management structures and budgets.

Late 1990s to 2000s

Macro-economic and policy environment

This period has seen signs that the earlier triumphalism of neo-liberal economics in international financial institutions is being replaced by a more sober assessment of developmental failures Citation[45]. This was symbolised most notably by the recent scathing attack on the International Monetary Fund’s “one size fits all” approach to structural adjustment by Joseph Stiglitz, the Nobel Prize-winning, former vice president and chief economist of the World Bank Citation[46]. Looking beyond the sector, poverty has re-emerged as a global concern in key macro-economic fora such as the G7 group of industrialised countries and international financial institutions Citation[47]. Health has again risen up the international aid agenda with the reassertion of the multiple links between poverty and poor health Citation[48].

This has produced a spate of recent initiatives, notably the Commission on Macro-Economics and Health, set up by the World Health Organization, whose report at the end of 2001 argues for an increased international investment in health of US$27 billion per year over the next five years Citation[49]. However, this must be set against a continuing gap between promise and reality by the industrialised countries in the funding of such international recommendations and commitments.

The Heavily Indebted Poor Countries Initiative, focusing on the 40 poorest countries, links debt relief to increased national spending on the social sector. Poverty reduction strategy papers (PRSPs), which set out the macro-economic strategy and policy instruments for producing growth which will benefit the poor, are now required by countries in receipt of World Bank “soft” loans (i.e. loans at concessional interest rates available to low-income countries) Citation[50]. The World Bank underwent its own conversion to the need to consult with the poor. Countries are therefore now expected to undertake poverty assessments involving discussions with poor people on their concerns and needs. Health concerns have figured prominently in these consultations. People have particularly stressed the devastating effects of major illness on their capacity to work, and the high costs of treatment which cause further impoverishment Citation[51]Citation[52].

International debates about poverty have seen a shift from using a predominantly income-focused concept towards concepts of poverty which focus on risk, vulnerability and exclusion Citation[53]Citation[54]. This has brought health risks more centrally into policy debate. That ill-health can be both a cause and a consequence of poverty has long been clear but, as already noted, it dropped off the international agenda during the 1980s. Consultations undertaken for the PRSPs have contributed to re-asserting this broader view of poverty, which is currently most influential in emerging social protection strategies. These new strategies have produced some experimentation with safety net mechanisms to protect the poor against catastrophic illness and provision of basic insurance for health care Citation[18]Citation[53]Citation[55]Citation[56].

International agency commitments to poverty reduction have become enshrined in the International Development Targets (IDTs), which were replaced by and mostly re-affirmed as the Millenium Development Goals (MDGs). Controversially, the IDT commitment to reproductive health for all was dropped from the MDGs, due to conservative opposition to the Cairo Agenda Citation[57]Citation[58]. What remains are some high-level sexual and reproductive health indicators, including maternal mortality ratios, under-five mortality ratios and targets for HIV/AIDS prevention.

There have also been changes in the “discourse” of international health. Whilst rights have continued to be the language of advocates and of the United Nations, the concept of health as a “global public good” has come increasingly to dominate international debate (e.g. in the Commission on Macro-Economics and Health). A “global public good” is defined technically as a good where one person’s use does not prevent another person from using it (“non-rivalrous”), the use of which is available to everyone (“non-excludable”) and the benefits of which extend across national boundaries. Examples of global public goods in health are disease eradication initiatives, shared biomedical research and development and affordable vaccines Citation[59]. In an era of concern (particularly by high-income countries) about the increasingly international nature of threats from communicable diseases, the concept of a global public good has neatly brought together self-interest with altruism.

The discourse of “health as a global public good” is embedded in the proliferation of international initiatives and coalitions of interest in international health issues among international agencies, national governments, private philanthropic organisations and commercial interests such as pharmaceutical companies. These new public-private partnerships aim to promote a common (so far usually biomedical) outcome, such as a particular drug or vaccine. The Global Alliance on Vaccines and Immunisation (GAVI), and the WHO Roll Back Malaria programme are examples.

Health sector reform responses

The main elements of the reform agenda - particularly financial and institutional reform and enhancing and regulating the role of the private sector - have continued to be important. However, in the current macro-economic and policy environment, governance and accountability issues have become a key concern. This is part of a larger international debate about the underlying conditions necessary for economic and social development and the role that governments play in creating them, and about how to improve the performance of bureaucracies and delivery systems in the health sector Citation[60].

This is therefore less a debate about who delivers the services than about how they are delivered. It also marks a concern to reinstate the role of government as the regulator and guarantor of trustworthy services, but in a context of multiple actors and interests. In practical terms, this has shifted interest to different ways of holding governments and service providers to account, and particularly the role of civil society organisations in this process. The chronology of this debate is clearest in successive World Development Reports and changes in dominant discourses in development economics. Here one can see the shift from earlier enthusiasm for privatisation of social goods and services and “rolling back the frontiers of the state” to a more considered position on the importance of the role of governments in regulating, managing or providing services Citation[9]Citation[53]Citation[61].

International poverty reduction targets and renewed emphasis on health and poverty links have brought social protection concerns to the fore, influencing reforms in health sector financing Citation[62]. Many countries are now considering insurance-based models for meeting health needs, or are assessing their viability Citation[52]. Increasingly, in poor and middle-income countries, a segmentation of populations is emerging in terms of how individual and household health care needs are going to be met. This consists of public or private insurance schemes for formal sector workers, basic health insurance or community financing for the moderately poor, and micro-credit and safety net funds for catastrophic illness for the very poor Citation[18].

These financing mechanisms raise larger issues about gender and social equity Citation[18]. It is also arguable that the strong emphasis in the poverty reduction lobby on individual and household-level protection (while a social good in many ways) is distracting attention from a broader public health agenda of preventive health care and environmental improvement, which particularly benefits poor women.

This period has also seen the rise of new international financing mechanisms, explicitly linked to the poverty reduction agenda. The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria was launched by the G7 countries in 2001, but at least initially it has fallen substantially short in terms of amounts pledged. The “new philanthropy,” best epitomised by the Gates Foundation, is resulting in large amounts of money going directly into mainly biomedical interventions, such as immunisation and improved drug supply. These huge grants have injected a new and uncharted dynamic into the international health scene. They have also introduced new tensions. After more than a decade of focus on health systems, such interventions increasingly seem to mark a return to “vertical” and biomedical approaches to health. They will co-exist uneasily with a systems-driven approach to sectoral reform.

Implications for reproductive and sexual health advocacy

The current macro-economic climate and policy agenda in international health pose a number of challenges. Under the Bush administration, powerful anti-progressive forces have mobilised to undo the gains in advocacy for sexual and reproductive health of the last decade. Health sector reforms have largely marginalised the Cairo agenda. Re-verticalisation is implicit in internationally-driven initiatives such as the Global Fund. All spell a warning for sexual and reproductive health.

A critical challenge is how to use effective advocacy to re-negotiate the policy and financial space for sexual and reproductive health services within both national health systems and at international level and building (or rebuilding) bridges between different stakeholders and sets of interests to try to find policy leverage.

First, much remains to be done to operationalise the expanded concept of sexual and reproductive health which emerged from the hard fought advocacy of ICPD and to go beyond programmes to tackle not only health systems reforms but the wider determinants of reproductive health, such as gender inequality. At the same time, advocacy for sexual and reproductive health also has to tread the line between an international vision of reproductive health for all and the urgent need for action on priority conditions, such as maternal morbidity and mortality, which means articulating an informed and forceful view on needs and priorities Citation[36]Citation[37].

In fact, all is not lost with the Millenium Development Goals. Maternal mortality remains a key target and the subject of international concern. HIV/AIDS is obviously there. Gender equality and empowerment are also there, particularly in the context of education targets. The task here will be to advocate for a clearer understanding and acceptance of the fact that the wider determinants of maternal mortality and STD/HIV transmission and prevention encompass all sexual and reproductive health, as encapsulated in the ICPD agenda. It is difficult to see how many of the MDGs can be achieved outside of that agenda.

Second, health sector reforms need attention at both national and international levels. Nationally, women’s health advocates need to look particularly at the implications of financing reforms for how they are likely to affect the availability and accessibility of sexual and reproductive health services Citation[63]Citation[64]. In pressing for greater national funding for reproductive health, advocates need to come to a view on the appropriate balance between concern with health systems strengthening and with more delivery and programme-focused actions, and create alliances with progressive systems reformers.

Third, international advocacy needs to gear up arguments that cannot be dismissed as “special interest” pleading by hardened systems reformers. Here, a bridge may usefully be constructed between rights-based advocacy approaches and other discourses around global spending commitments, such as global public goods. A powerful case needs building for why reproductive and sexual health is more than a matter of local or national concern. This means learning from the success, for instance, of the Commission on Macro-Economics and Health and of the education lobby in producing powerful “human capital” arguments for increased health and education expenditure Citation[49]Citation[65]. Perhaps now is the time to start arguing for a macro-economics commission on reproductive health?

Acknowledgements

This is an expanded version of a presentation at “Health Sector Reforms: Implications for Sexual and Reproductive Health Services”, 25–28 February 2002, Bellagio, Italy. Thanks to participants for their comments and to Jan Boyes at IDS for editorial assistance.

Notes

1 The continuing tension in discussions of the role of private provision in the health sector reflects broader macro-economic debates about public versus private social service provision Citation[16]. The World Bank and IMF are criticised for putting forward privatisation as their major policy response to government failure and poor public sector performance, and critics are deeply suspicious of attempts to engage with the private sector in health. Others consider engagement to be a pragmatic response to the existing status quo in many countries, where private health care use and expenditure outstrips that in the public sector. Neither view is “wrong”. In fact, the private sector is not one unified institution, but covers a heterogeneous range of services – traditional healers, non-profit providers ranging from women’s health groups to churches to local pharmacies, as well as the for-profit sector. It is therefore important to make clear distinctions between them when considering the role of these services.

References

- A. Cassels. Health sector reform: key issues in less developed countries. Journal of International Development. 7(3): 1995; 329–347.

- P. Berman. Health Sector Reform in Developing Countries. 1995; Harvard University Press: Boston.

- C. Simms, M. Rowson, S. Peattie. The bitterest pill of all: the collapse of Africa’s health system. 2001; Save the Children Fund UK: London.

- Standing H. Frameworks for Understanding Gender Inequalities and Health Sector Reform: An Analysis and Review of Policy Issues. Working Paper Series No 99.06 Cambridge MA: Harvard Center for Population and Development Studies, 1999

- Standing H, Bloom G. Pluralism and Marketisation in the Health Sector: Meeting Health Needs in Contexts of Social Change in Low and Middle Income Countries. IDS Working Paper 136. Brighton: Institute of Development Studies, 2001

- M. Ainsworth, P. Shaw. Financing Health Services through User Fees and Insurance: Case Studies from sub-Saharan Africa. 1996; World Bank: Washington DC.

- D. Nabarro, A. Cassels. Strengthening Health Management Capacity in Developing Countries. 1994; Overseas Development Administration: London.

- Kutzin J. Experience with Organizational and Financing Reform of the Health Sector: Current Concerns. SHS Paper No. 8 (SHS/CC/94.3). Geneva: World Health Organization, 1995

- World Bank. Investing in Health: World Development Report. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993

- H. Standing. Gender and equity in health sector reform programmes: a review. Health Policy and Planning. 12(1): 1997; 1–18.

- S.W. Jarrett, Amaah Ofasu. Strengthening health services for MCH in Africa: the first four years of the Bamako Initiative. Health Policy and Planning. 7(2): 1992; 164–176.

- B. McPake, A. Hanson, A. Mills. Community financing of health care in Africa: an evaluation of the Bamako Initiative. Social Science and Medicine. 36(11): 1993; 1383–1395.

- D. Sahn, R. Bernier. Has structural adjustment led to health sector reform in Africa. P. Berman. Health Sector Reform in Developing Countries. 1995; Harvard University Press: Boston.

- I. Quadeer, K. Sen, K.R. Nayar. Public Health and the Poverty of Reforms: The South Asian Predicament. 2001; Sage: New Delhi.

- D.A. Leon, G. Walt, L. Gilson. International perspectives on health inequalities and policy. BMJ. 322(10 March): 2001; 591–594.

- D. Giusti, B. Criel, X. Bethune. Public versus private health care delivery: beyond the slogans. [Viewpoint]. Health Policy and Planning. 12(3): 1997; 193–198.

- A. Cassels. Aid instruments and health systems development: an analysis of current practice. Health Policy and Planning. 11(4): 1996; 354–368.

- Standing H. Gender impacts of health reforms – the current state of policy and implementation. Women’s Health Journal 2000;3–4(July–Dec):10–19

- G. Walt. Health sector development: from aid co-ordination to resource management. Health Policy and Planning. 14(3): 1999; 207–218.

- Evers B. Economic liberalisation – Health sector reform – Gender and reproductive health. Working document for discussion at Reproductive Health Advisory Group meeting, October 1999

- A.B. Zwi, A. Mills. Health policy in less developed countries: past trends and future directions. Journal of International Development. 7(3): 1995; 299–328.

- Loewenson R. Public Participation in Health: Making People Matter. IDS Working Paper 84. Sussex: Institute of Development Studies, 1999

- Cornwall A, Lucas H, Pasteur K. (editors) Accountability through participation: developing workable partnership models in the health sector. IDS Bulletin 2000;31(1)

- C. Collins, A. Green. Decentralization and primary health care : some negative implications in developing countries. International Journal of Health Services. 24(3): 1994; 459–475.

- R.L. Kolehmainen-Aitken. Myths and Realities about the Decentralization of Health Systems. 1999; Management Sciences for Health: Boston.

- Simms C, Milimo JT, Bloom G. Reasons for the Rise in Childhood Mortality During the 1980s in Zambia. IDS Working Paper 76. Brighton: Institute of Development Studies, 1998

- Bloom G, Lucas H with Edun A, et al. Health and Poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa. IDS Working Paper 103. Brighton: Institute of Development Studies, 2000

- Bloom G, Wilkes A, editors. Health in transition: reforming China’s rural health services. IDS Bulletin 1997;28(1)

- M. Das Gupta, L.C. Chen, T.N. Krishnan. Health, Poverty and Development in India. 1996; Oxford University Press: Delhi.

- Murray CJL, Lopez AD, editors. The Global Burden of Disease, Vol.1. Boston: Harvard School of Public Health/World Health Organization/World Bank, 1996

- Reichenbach LJ. Priority Setting in International Health: Beyond DALYs and Cost Effectiveness Analysis. Working Paper Series No 99.06. Cambridge MA: Harvard Center for Population and Development Studies, 2001

- K. Hanson. Measuring up: gender, burden of disease and priority setting. G. Sen, A. George, P. Ostlin. Engendering International Health: The Challenge of Equity. 2002; MIT Press: Boston.

- E. Nygaard. Is it feasible or desirable to measure the burdens of disease as a single number. Reproductive Health Matters. 9(15): 2000; 117–125.

- Mills A, Broomberg J. Experiences of Contracting: An Overview of the Literature. WHO/ICO/MESD.33. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1998

- E. Smith. Working with Private Sector Providers for Better Health Care: An Introductory Guide. 2001; Options/London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine: London.

- J. DeJong. The role and limitations of the Cairo International Conference on Population and Development. Social Science and Medicine. 51: 1999; 941–953.

- Petchesky R. Reproductive and Sexual Rights: Charting the Course of Transnational Women’s NGOs. UNRISD Occasional Paper 8. Geneva: United Nations Research Institute for Social Development, 2000

- International Council on Management of Population Programmes. Managing Quality Reproductive Health Programmes: After Cairo and Beyond. Report of an International Seminar, Addis Ababa, December 1996. Kuala Lumpur: ICOMP, 1997

- Hardee K, et al. Reproductive health policies and programs in eight countries: progress since Cairo. International Family Planning Perspectives 1999;25(Suppl):S2–9

- S.H. Mayhew, L. Lush, J. Cleland. Implementing the integration of component services for reproductive health. Studies in Family Planning. 31(2): 2000; 151–162.

- Mayhew SH, Walt G, Lush L. Donor involvement in reproductive health: saying one thing and doing another? International Journal of Health Services (forthcoming 2002)

- UN Population Fund. Reorientation of national family planning programmes towards a broader reproductive health approach, including family planning and sexual health, in East and South East Asia. Occasional Paper Series No 5, New York: UNFPA, 1998

- Walker G. Implementation challenges of reproductive health, including family planning and sexual health: issues concerning the integration of reproductive health components, 1999. At: http://www.unescap.org/pop/icpd/walker.htm, accessed 11 April 2002

- M. Foster. Lessons of Experience from Health Sector SWAps. 1999; CAPE/Overseas Development Institute: London.

- Stiglitz JE. More instruments and broader goals: moving toward the post-Washington consensus. World Institute for Development Economics Research, WIDER Annual Lectures 2. Helsinki: WIDER, 1998

- Stiglitz JE. What I learned at the World Economic Crisis, 2000. The Insider. The New Republic On Line. At: http://www.thenewrepublic.com/041700/stiglitz041700.html, accessed 18 July 2001

- Sachs J. A new global consensus on helping the poorest of the poor. Proceedings of the World Bank Annual Conference on Development Economics, Washington: IBRD, 2000. p 39–47

- D. Gwatkin. Poverty and inequalities in health within developing countries: filling the information gap. D. Leon, G. Walt. Poverty, Inequality and Health: An International Perspective. 2000; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 217–246.

- World Health Organization. Macro-economics and Health: Investing in Health for Development. Report of the Commission on Macroeconomics and Health. Geneva: WHO, 2001

- Review of the PRSP Experience. Issues Paper for the International Conference on Poverty Reduction Strategies, 14-17 January 2002. Washington DC: World Bank. At: http://www.worldbank.org/poverty/strategies/review/index.htm, accessed 9 May 2002

- D. Narayan, R. Chambers, M.K. Shah. Crying Out for Change. Voices of the Poor. 2000; World Bank: Washington DC.

- Gwatkin DR. Reducing Health Inequalities in Developing Countries. In Oxford Textbook of Public Health, 4th edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002. p 1791–1810

- World Bank. Attacking Poverty: World Development Report 2000/2001. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001

- D.R. Gwatkin. Health inequalities and the health of the poor: What do we know? What can we do?. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 78(1): 2000; 3–18.

- P. Gertler. On the road to health insurance: the Asian experience. World Development. 26(4): 1998; 717–732.

- Pollner JD. Managing Catastrophic Disaster Risks Using Alternative Risk Financing and Pooled Insurance Structures. Washington DC: World Bank, 2001

- F. Girard. Reproductive health under attack at the United Nations. [letter]. Reproductive Health Matters. 9(18): 2001; 68.

- M. Berer. Images, reproductive health and the collateral damage to women of fundamentalism and war. Reproductive Health Matters. 9(18): 2001; 6–11.

- Kaul I, Grunberg I, Stern MA. Global Public Goods: International Cooperation in the 21st Century. New York: Oxford University Press for UN Development Programme, 1999

- World Health Organization. Health Systems: Improving Performance. World Health Report 2000. Geneva: WHO, 2000

- World Bank. The State in a Changing World. World Development Report. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997

- International Labor Organization. Income Security and Social Protection in a Changing World: World Labor Report 2000. Geneva: ILO, 2000

- E. Gómez. Gender, equity and access to health services: an empirical approximation. Pan American Journal of Public Health. 11(5/6): 2002; 327–334.

- Standing H. Towards an equitable financing strategy for reproductive health. IDS Working Paper 155. Brighton: Institute of Development Studies, 2002

- P. Schultz. Investment in Women’s Human Capital. 1995; University of Chicago Press: Chicago.