Abstract

Some 84,000 children with HIV/AIDS live in the Côte d'Ivoire, where very little therapeutic or psychological help is available to them. The Yopougon Child Programme of the “Agence Nationale de Recherche sur le Sida” was launched in Abidjan in October 2000. It provides services for HIV-infected children and psychological consultations for children and their parents. This paper is about the psychosexual development of the HIV-positive adolescents in the Programme, 11 girls and 8 boys aged 13–17, their problems with HIV-related physiological and psychosexual changes, and relationships with their parents. The information was gathered in individual therapy sessions, group discussions and family support sessions. Bodily development was of major importance to these adolescents, particularly among those who had not yet developed secondary sexual characteristics and were shorter and weighed less than their peers. Those who had not achieved puberty were unable to participate in traditional rituals and worried whether they could ever marry or have children. In most cases, adolescents with HIV have been infected by a sexually transmitted virus without having had sexual relations themselves. They need support dealing with their sexual development and sexual feelings, along with medical care, in a context in which HIV infection is a secret, impossible to talk about with their peers.

Résumé

Environ 84 000 enfants séropositifs vivent en Cô te d'Ivoire, où ils ont accès à peu de soins ou de soutien psychologique. Le programme Enfants Yopougon de l'Agence Nationale de Recherche sur le SIDA a été lancé à Abidjan en octobre 2000 et fournit des services aux enfants séropositifs et des consultations psychologiques aux enfants et à leurs parents. L'article décrit le développement psychosexuel des adolescents séropositifs participant au programme, 11 filles et 8 garçons de 13 à 17 ans, les problèmes que suscitent chez eux les changements physiologiques et psychosexuels liés au VIH, et leurs rapports avec leurs parents. L'information provient de séances individuelles de thérapie, de discussions de groupe et de sessions de soutien aux familles. Le développement corporel était très important pour ces adolescents, notamment pour ceux dont les caractéristiques sexuelles secondaires n'étaient pas encore apparentes, et qui pesaient et mesuraient moins que leurs camarades du même âge. Ceux dont la puberté n'était pas achevée ne pouvaient participer aux rituels traditionnels et se demandaient s'ils pourraient se marier et avoir des enfants. La plupart des adolescents avaient été infectés par un virus sexuellement transmissible sans avoir eu de rapports sexuels. Outre les soins médicaux, ils avaient besoin d'aide pour affronter leur développement sexuel et leurs sentiments sur la sexualité, dans un environnement où le VIH est un secret dont ils ne peuvent parler avec leurs camarades.

Resumen

Unos 84,000 niños con VIH/SIDA viven en Côte d'Ivoire, donde tienen acceso a muy poca ayuda terapéutica o psicológica. En octubre 2000, se inauguró en Abidjá n el Programa Infantil Yopougon de la Agence Nationale de Recherche sur le Sida, que provee servicios para niños infectados con VIH y consultas psicológicas para los niños y sus padres. Este artículo examina el desarrollo psicosexual de los adolescentes que participan en el programa (11 niñas y 8 niños de entre 13 y 17 años), sus problemas con los cambios fisiológicos y psicosexuales relacionados con el VIH, y sus relaciones con sus padres. La información se recopiló en sesiones de terapia individual, en plá tica en grupo, y en sesiones de apoyo a lafamilia. A estos adolescentes les importaba mucho su desarrollo fı́sico, especialmente a aquellos que todavı́a no habı́an desarrollado rasgos sexuales secundarios y que eran má s pequeñ os que sus pares. Los niñ os y las niñas que no habı́an alcanzado la pubertad no podı́an participar en rituales tradicionales y les preocupaba la posibilidad de no poder casarse ni tener hijos. La mayorı́a de los adolescentes con VIH está n infectados con un virus transmitido sexualmente sin que ellos hayan tenido relaciones sexuales. Necesitaban apoyo parasobrellevar su desarrollo y sus sentimientos sexuales, y la atención médica, en un contexto donde la infecció n con VIH era secreto e imposible de abordar con sus pares.

Some three million children throughout the world have HIV/AIDS,Citation1 of whom 84,000 live in Côte d'Ivoire,Citation2 where very little therapeutic or psychological aid is available to them. In most cases, HIV infection was acquired perinatally.Citation3 While there are many studies of HIV-infected children and adolescents in Africa, most of them concern the situation of AIDS orphans, and prevention and awareness-raising campaigns on HIV/AIDS for adolescents.Citation4, Citation5

The psychosexual development of HIV-positive adolescents has not yet been the subject of specific studies in Africa. However, studies among large numbers of HIV-positive adolescents in Europe illustrate the urgent need for such research to improve care for these adolescents.Citation6 In a review of the literature on the impact of HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa, Geoff Foster and John Williamson noted that the only psychological aspects observed were psychosocial problems.Citation7 These have been well studied in relation to AIDS orphans, i.e. the stigmatisation and depression that results.

On the other hand, existing research among HIV-positive adolescents has lacked a psychosexual dimension. In general, adolescence is a period in which young people feel caught in an in-between world.Citation8, Citation9 This is a period of conflict, involving self-centred crises and questioning of identity. Adolescents are often preoccupied with their bodies, with the development of their genital organs and secondary sex characteristics. They may also be fascinated by risk-taking and playing with death.Citation10, Citation11

The Yopougon Child Programme

The Yopougon Child Programme, a project of the Agence Nationale de Recherche sur le Sida (ANRS, National AIDS Research Agency), was launched in Abidjan in October 2000, to address the lack of appropriate care and provide services for a growing number of HIV-infected children. To date, 250 children, including 19 adolescents, have received free medical and psychological care, with community support. In addition to treatment for AIDS-specific conditions, the national medical treatment programme has provided them with access to antiretroviral therapy free of charge, according to their needs. Psychological therapy has also been provided for all the children covered under the Programme, in order to produce an appropriate profile of these patients. A psychological consultation has been available both for psychologically disturbed children and their parents, whenever they express the need, as HIV/AIDS has been the cause of both psychological and physical suffering. This differs according to age, sex, living conditions and life experience of the children concerned. Citation2 Citation12 Citation13 Citation14

Characteristics of the adolescents in the Programme

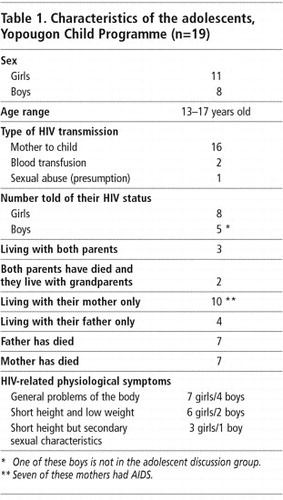

Nineteen of the children, 11 girls and 8 boys, were aged 13 to 17 and had specific problems connected with HIV, as well as the usual physiological and psychosexual changes found in adolescents and pre-adolescents. The parents of three were both alive. Seven had lost their fathers, and seven others had lost their mothers. Two were orphans with neither father nor mother still alive, and were cared for by their grandparents. Some were children of single mothers who had died and had been taken in by the family on the mother's side.

Most of the adolescents came from underprivileged socio-economic classes but attended school nevertheless. There were only four cases of school drop-outs. However, some pupils were several years behind with their schooling, and in a few cases they were very unlikely to get beyond the first stage of secondary education, given their poor financial situation and health. However, in spite of economic difficulties, their parents or guardians were deeply concerned that their studies should continue, especially when the mother was raising the child on her own or when, after her death, the child was being raised by a woman from the maternal family.

Sixteen of the 19 adolescents had contracted HIV infection through their mothers perinatally, and two through a blood transfusion. Sexual abuse was suspected in the one remaining case but was never clearly established. Twelve adolescents, eight girls and four boys, were aware of their HIV serostatus. In the case of the other seven, there had been strong opposition to disclosure from the parents, who were not prepared to tell their children the truth about their condition. Seven of the ten living with their mothers had AIDS, and four of them were taking antiretroviral treatment.

Methodology

We first met this group of adolescents as clinical psychologists during psychological support sessions provided under the aegis of the Yopougon Child Programme, which included both individual interviews and, when requested by the parents, family support sessions for both parents and children. The 12 adolescents who were aware of their HIV status were also offered the possibility of meeting in monthly group sessions with psychologists, where they could talk freely and discuss subjects of their own choice. These sessions allowed them to share their anxieties regarding HIV infection and treatment, and also to discuss the experience of adolescence more broadly. The topics covered included parent–adolescent relations, the impact of medical treatment on their lives, how they handled the secret of their HIV status, and the development of their bodies. These sessions made them feel safe to put into words things they had never dared to talk about before and which would have been impossible in any other environment.

A qualitative approach was used to gather the information presented in this paper and came from interviews in individual therapy sessions, group discussions and family support sessions during periods of distress and crisis, as well as data from the medical and psychological files on these adolescents. These permitted us to make detailed observations regarding their emotional experiences and personality development. We did cross-sectional analysis of the information gathered according to the type of problems the adolescents identified, and how they dealt with these problems and with their relationships with others. Overall, our approach highlighted the perceptions of these young people regarding their bodies and sexuality. The personal perceptions of the adolescents related here are based on what they themselves told us when we talked with them.

The importance of the adolescent body

Their bodies were of major importance to these adolescents.Citation8 This was where they felt the pain and located the stigma attached to HIV. The state of their bodies should have been the source of proof of their social integration in their age group, a guarantee of recognition by their peers and a sign of the essential development of relations with their parents. Their bodies were therefore subjected to all manner of contemplation, self-inspection, appraisal and deciphering, but also of daydreaming and denial.

The prevailing and most visible feature among six of the eight girls and two of the four boys in the discussion group was their short height and low weight compared to others of the same age.

The two boys who were concerned about their height presented an exceptionally high level of intellectual development, while in their emotional relationships they adopted an immature type of behaviour similar to that of pre-adolescents (a social status which they were able to identify with because of their height). On the other hand, perhaps in compensation, they also exhibited characteristic adolescent behavioural disorders such as nightly outings, drinking alcohol and absenteeism from school. Both boys expressed their adolescent crisis by opposing the standards and limitations imposed by society.

One of the two boys, René,Footnote* was the child of an unknown father and rejected by his half-brothers. He lived with a deep sense of identification with his mother and even went so far as to reproduce her behaviour. His mother, who felt helpless due to the precariousness of her social and economic situation and because both she and her son were HIV-positive, turned to drink periodically. In spite of his mother's prohibition, René seemed to find by going out at night and in bouts of drinking one way of expressing both opposition and self-affirmation. René rarely took initiative in the group. His interventions highlighted his lack of self-confidence and how deeply he was hurt by a body and a face that “people” considered ugly. He still kept in the back of his mind whispers heard during his childhood:

“Such a puny and ugly child! Why on earth does his mother persist in caring for him? He will certainly not survive. And even if he does, what is he going to look like?”

Simon, who until his father's death enjoyed the over-protective affection of both his parents, was trying to break free from his mother, refused to go to school regularly and committed petty theft. He scorned any kind of authority and was at risk of becoming a delinquent.

Eloi came from a background of manual work and had to earn a living from an early age. He was of average height but had some behavioural difficulties. Beyond a strong desire for independence vis-à-vis his family, we noted his extreme vigilance regarding any comments on his physical appearance or minor skin diseases, to which he was always ready to burst out with physical or verbal aggressiveness. Personal and family honour were of fundamental importance for him, and he often had fights with his peers. His body was also important to him, as demonstrated by the particular care he took of his looks, e.g. by wearing jewellery and in his choice of clothes, studied care of hairstyle and so on.

The fourth boy in the group, Martin, did not have any particular difficulties due to his height or behaviour. We did, however, observe a certain lack of confidence in his body whenever he had to undress, in the swimming pool, for instance. But we could not link his behaviour specifically to HIV, which he had acquired through a blood transfusion.

The boys rarely talked about sexuality although they seemed to be well informed on the subject by their friends. As with pre-adolescent boys, their relations with girls were jeeringly aggressive and they made fun of sexual or sentimental situations. Except for Eloi, they did not care how they dressed and tended to minimise their apparent sexual characteristics. On the whole, we observed little indulgence in sexual fantasy and a preference for action.

Among the girls, the appearance or not of secondary sexual characteristics with which their age group identified had an even more dramatic influence. Three of the eight girls, who were of average height and weight, experienced their bodies the same as almost any other adolescent would. The problems they expressed were mainly connected with the “quality” of their bodies and whether they might deteriorate. Their major preoccupation was with not falling ill and avoiding the outward signs of HIV-related disease that would expose their secret to the outside world. For them, being as thin as fashion might require was, in the eyes of people in Côte d'Ivoire, too obvious a sign of AIDS.

Three of the other five girls were shorter than average in height but had developed secondary sexual characteristics. Self-esteem was frequently damaged in this group. It was hard for the girls when they mentioned their age to have to face the resulting look of disbelief or to feel that they might be taken for dwarves. Even a stranger's inquisitive look or an expression of simple curiosity rendered this all the more painful a secret, which was difficult to hide. As a result, they developed a negative preoccupation vis-à-vis their bodies, refusing to accept that they had a body that did not correspond to what they needed from it. One of these three girls, however, was socially active; she worked with her grandmother selling goods in the market and paid ostentatious attention to her looks (make-up, hairdo, feminine clothes). For the two others, an under-developed body made it easier to come to terms with being behind in school and allowed them to be better integrated in their class. When these girls did achieve good marks, the other pupils found it difficult to accept due to their short height for their age and made fun of the girls as “dwarves”.

The remaining two girls looked like pre-adolescents physically, with no outward signs of puberty, and their physical appearance was combined with emotional and psychological immaturity, though not with lack of sexual awareness. Their worlds were still focused on playing. They took no initiative but felt that they had to obey adults completely and were not authorised to act on their own. They had hardly any social interests other than in their families and a limited number of friends.

It was typical of this group not to be bothered about life's problems. We did not observe any adolescent-type intellectualisation about major life questions or profound discussions except for the usual outbursts against their mothers or mother-surrogates. However, in spite of the fact that their bodies were not growing or developing, and because of social pressures and internal psychological changes, these girls would fantasise about their bodies sexually. They thus lived in a state of anticipation, waiting for their bodies to mature and at the same time wishing that their bodies could already inspire interest. The waiting for changes to occur was agonising for them.

Indeed, all eight girls, who remained small for their age, lived in a state of anguish because they were not growing or developing enough. “What if there will never be any change?” At the same time, they continually feared these physical changes taking place. Being in this in-between phase, the question of how to present their “incomplete” bodies was of ceaseless concern–clothes had to be fashionable and looking like a child had to be avoided. Unable to rely on an inner defence mechanism, they had to build an outer shield. This situation was one of the most important sources of conflict with their mothers. In spite of financial difficulties, the daughters wanted to live up to the usual adolescent standards, while the mothers, worried about their daughters' desire to look seductive, would try to use the excuse of their daughters' small height to ask, even with a 15-year-old, “But she is still only a child, isn't she, doctor?” and continue to dress her as though she were only ten. Thus, we encountered all the elements of adolescent crises against a background of physical immaturity in the girls, with the result that their reactions were even more unpredictable and less easy to understand than with other adolescents of their age.

The interviews and discussion groups emphasised that most of the girls deeply lacked confidence in bodies which they could not appreciate and which, moreover, were eventually likely to betray them due to HIV-related disease. They dared not value their bodies even when forced to act out the psychosexual behaviour of an adolescent in the absence of its corollary, puberty. They played at “seducing” but did not talk about sexuality as such, or if they did, it was only in the form of a pre-adolescent kind of teasing.

The magical value of anti-HIV treatment

In this context, antiretroviral treatment against HIV acquired a magical value: the miracle pills would set in motion all the normal physiological functions. The stakes were important. The parents could dream that one day their children would lead a normal life. The adolescents could hope that medication would enable them to belong fully to their own age group without the development of their bodies and their feelings lagging behind.

Treatment therefore sometimes became an object of enthrallment for this group, but at the same time its symbolic value became a source of all their other emotional upsets. Not taking the drugs symbolised committing suicide or self-mutilation, and a means of punishing or manipulating their mothers or the nursing staff.Citation11, Citation12 Because treatment was so important to their parents, the adolescents would use it to make them suffer. Rina, for example, aged 15, pretended to swallow the pills under pressure from her mother, but then spat them out and threw them under the table. When her mother discovered this, the conflict between them was dramatic as, obviously, the mother took it as pure provocation.

Antiretroviral treatment visibly improved the physical condition of those adolescents who adhered to the requirements for taking it, but awareness of this benefit did not prevent them from abusing the therapy. Everyday life was sustained by the hope of continuing well-being and by the hopes and encouragement of their parents and the nursing staff. Whenever there was any kind of problem in their relationships with these adults, at whatever level, problems with compliance in taking their medication would manifest themselves.

The 12 adolescents who knew they were HIV-positive needed to talk about and understand their treatment and the difficulties of adherence, and they needed encouragement and support. That others should believe that they had a future was a confirmation of their own sense of hope for themselves. However, this was regularly damaged every time an HIV prevention campaign came out with a description of the devastating effects of the disease.

“Doctors on TV, they say that we are going to die. But I take my pills because I want to live”.

The link between medication and life was obvious to them and regularity in complying with treatment was always close to the heart of their desire for life.

The condition of not knowing

The other seven adolescents, who had not been told that they had HIV, experienced an anguished dissatisfaction that was linked with unvoiced feelings and their awareness of open secrets about their health.Citation14, Citation15 Taking medication whose purpose had not been fully explained to them made them anxious. Although their parents and guardians persisted in believing that they alone really knew what was happening to their children, these seven adolescents, through information gathered from all around them, had drawn their own conclusions. As a result they adopted either a provocative or self-defensive attitude towards their parents and anyone else who knew their “secret”.

Body, body image and culture

In the Côte d'Ivoire, social custom has traditionally dictated a number of rituals to celebrate the different stages of a girl's life, e.g. at the onset of menstruation and of secondary sexual characteristics, as well as at marriage, births, widowhood and so on. Parents are normally proud to acknowledge the development of puberty in their offspring, who are thereby recognised as belonging to their particular social group through these rituals. As far as boys are concerned, however, rites of passage are less usual today. There are fewer and fewer secret societies where youths are initiated, and few parents make use of them for their offspring. Circumcision of boys now takes place a few months after birth and there is no particular ritual to celebrate it. Social integration therefore takes place essentially within a boy's friendship group, where group outings, drinking, smoking and experimenting with sex are typical adolescent behaviours. Later on, the need to earn money to care for one's parents, having children as a sign of virility and getting married in order to have an organised home life become important. But for those living with HIV and AIDS, sex, children and marriage are anguished preoccupations that only lead to depression. “Can I, as all the others, have a wife and children one day…?” “Will I live long enough so that my parents can enjoy the fruit of my labour…?” These are questions which the medical staff cannot answer. So it is all the more understandable that boys prefer other forms of proof of adult social integration such as aggressiveness and drinking.

Although traditional rituals are still considered important and celebrated for girls, parents cannot count on their HIV-positive daughters reaching puberty by the usual age, and hence cannot present their daughters for the celebration of these rituals. Nor can they project themselves into the future with their daughters as they are not sure of their own survival. Thus, HIV-positive girls have to find a way to cope with the fact of being excluded from the rituals and of their friends going through the rituals without them.

For them, sex remains a taboo that cannot be discussed. Talking about sex, in spite of all the varnish of modern life, is still not tolerated in Côte d'Ivoire and is usually confined to jokes, playful remarks or forbidden words. Talking about oneself, about sex or private feelings is “not done”. Information about sex and sexuality is hidden, gathered in fragmented bits and pieces within the limitations of what is culturally permitted. Sexual education is all the more taboo in families where the parents bear the weight not only of the cultural taboos but also of their own guilt at having acquired HIV sexually. Adolescents in this situation suffer from being out of place in more ways than one during this period of their growing up, trapped in an immature body that cannot meet their expectations and living with many agonising questions that remain unanswered because it is forbidden to ask them.

Adolescent psychosexual development

Children with HIV/AIDS are born into and grow up in a fragile emotional environment. Families are being totally re-organised because of AIDS deaths, with profound effects on the self-identity and development of young people, as well as on how they identify with other people in their lives. Whether or not they actually knew their fathers and mothers was of particular importance to these adolescents. Because of AIDS, they may have lost one or both parents at an early age, or their parents may be relatively unavailable because they have to fight to stay alive themselves or struggle to provide for the vital needs of the family on their own. Among the adolescent girls in the group, for example, Morine had a very negative image of the father she never knew and blamed him for having infected her mother. In fact, she considered men as particularly dangerous beings, all too ready to exploit women. Rina did not know her father either, and she was in search of a substitute able to impose authority as a paternal figure; she thus often purposely disobeyed the law and defied school regulations.

Surrogate parents who may be more (or perhaps less) caring appear on the scene and may act over-protective and anxious, or may become exasperated by the children's numerous HIV-related illnesses.Citation10 Citation15 Citation16 Citation17 We found that many of these children had been crushed by their experiences. Some had been infantilised, while others had become independent in ways that they should never have had to do. For example, because of their parents' illness, many of the children had to learn at an early age how to prepare meals, travel on public transport for long distances and sometimes at night, figure out how to live alone in a home deserted by hospitalised parents, play the part of an adult in looking after a helpless parent, and then suffer the death of their parents.

Their psychosexual personalities were formed in the context of these difficulties. When they became adolescents, the difficulties trying to cope on their own that they had encountered as children returned, but their reactions were very different. Simone, who was never recognised by her father or his family, is today expressing her femininity through her body and visibly presents herself as a seductress. It is her way of taking revenge on life and she conveys this with outrageous make-up and extravagant clothes, unperturbed whether she shocks or not. “Even without my father, I have become a person.” She has confirmed her existence as an individual during this period of her adolescence.

Symbolic importance of the father–child relationship

Five of the 11 adolescent girls had lost their fathers and four others were no longer in touch with theirs. For these nine adolescents, the father represented the family's history and this affected their relationships with their mothers. Whether idealised as the healer of all evils or cursed as the cause of their infection, their father's image was a fluctuating one, making it possible to believe in the innocence of their mother. The father was seen as an ambiguous and unreliable figure, which did not encourage the girls to see themselves as having a relationship with a man very easily.

In the case of the two adolescent girls who were living with their fathers but without their mothers, the father was an important figure in their discourse. These two fathers poured love and care on their daughters, in both a paternal and maternal way. This relationship was ultimately a confining and exclusive one which created the problem for these two girls of developing a fixation on men primarily as protectors.

Of the four boys in the peer group, three had lost their fathers but were supported by their mother's family. It was difficult for them to talk about their fathers. They said their mothers could not talk about their fathers either and felt guilty about them. The fourth boy was rejected by his father and his paternal family, and considered his father responsible for his socio-economic difficulties. The substitute for absent fathers was in general a maternal uncle or older brother. These adolescent boys generally had a good relationship with their mothers. They denied the likely relation between their fathers and AIDS in order to protect their mothers from feeling guilty or grieving.

The only adolescent boy who lived with his father had contracted HIV infection through a blood transfusion. He had a good relationship with his father, but it was his brother who supported him because his father was quite old.

Symbolic importance of the mother–child relationship

Children inherit their parents' past, especially that of their mothers, and this is very important in the context of mother-to-child transmission of HIV. Parents and mothers in particular feel exceptionally upset about having infected their children, and that affects their own self-confidence as well as their confidence in others.

In the case of the boys who were infected through their mothers, their relationship with her was troubled because it was related to the sexuality of the mother and turned her into a possible sex object. Thus, the boys felt sex was at the root of all their misfortune. Because of their disease, they felt that in some way, they were being punished for their mother's sexuality, and thus “castrated” even before committing a misdeed. The death of the father (for three of the four boys) made the situation more complex. In practice, the father was hardly ever mentioned and the relationship with the mother oscillated between possessiveness and aggressive opposition. The search for independence was a constant one but accompanied by multiple demands vis-à-vis the mother. Here too, ambivalence was constant at all levels.

When the eight girls learned of their HIV-status and the fact that their mothers had transmitted HIV to them at birth or soon after, they put all the blame on their mother, turning her into a “non-person”. As a result mother–child relations became aggressive and the girls engaged in open conflict with their mothers, refusing to respond to their expectations. In one case, however, the daughter regarded her unknown father as the person responsible for transmitting the virus to her mother and thereby to her. When she reached adolescence it was impossible for her to place any trust in a father figure but that led to a tremendous closeness with her mother. In all cases, however, we observed a lack of self-acceptance prompted all the more by the absence of signs of puberty in their bodies. The adolescent girls found it particularly difficult to identify with their mothers and to embark upon womanhood both sexually and socially.

We also observed that there were mothers who refused to see that their daughter was an adolescent who was growing up and ready to assert herself. The tendency to overprotect the infected children combined with their fragile health made it difficult to foresee a constructive separation and projection into the future. With her own painful past experience, due to HIV infection, the mother was unable to detach herself from the adolescent and allow her the autonomy she aspired to. In the words of one mother of a 14-year-old girl:

“My daughter does not want to grow up nor does she want to detach herself from me….she just can't. I myself, I refuse to let her out on her own without me because she can't follow her treatment without me–I have to take care of everything.”

In addition, the immature bodies of these adolescent girls only contributed to the mothers' belief that their daughters could not possibly be an object of sexual pleasure for someone else. Thus, their daughters remained fragile beings in need of protection. Yet the mothers also experienced ambivalence. On the one hand, they wished to free themselves from the constraints of caring for their daughters and would have liked them to become autonomous and emotionally mature; at the same time, they refused to grant that autonomy to their daughters for fear that they would not be able to defend themselves in life.

The need for psychosexual counselling and support

In most cases, adolescents with HIV have been infected by a sexually transmitted virus without having had sexual relations themselves. We found through our programme that they needed support dealing with the beginnings of their sexual development and their sexual feelings, along with medical care, in a context in which their HIV status was a secret that was impossible to talk about with their peers.

Individual interviews with a psychologist and discussion groups made it possible for both the adolescents and their parents to give voice to their feelings about their bodies and body images and their approach to sexuality. For our part, we gave them information about HIV-related disease and its treatment, and about sexuality.

We recommend that any programme that assumes responsibility for HIV-infected children must also include a component with psychological support and counselling, for adolescents in particular. This means taking into account frustrations experienced in relation to bodily development, because the body becomes identified as the carrier of the virus and marks the person as negatively different from others. Psychological support makes it possible to translate suffering into words and facilitates an acceptance of the situation. It will not be successful, however, without the support of parents and peers and should be undertaken after the youngster is first informed of his/her HIV status. We believe this should be done as early as pre-adolescence (12–13 years of age) so that the child can overcome the depression that often occurs, and before there is a more serious maladjustment expressed during adolescence, which HIV makes all the more difficult. When such support is adequately provided from an early stage, it is possible to optimise parent–child relations, to encourage the child to adhere to medical treatment, to re-establish an identity that acknowledges HIV and is able to replace the inability to adapt by verbalising and understanding the problems.

The adolescents in our care are still ill-at-ease where sex is concerned. Discussions on the subject remain difficult and must be approached individually. Compared with other adolescent groups, the emotional burden that must be dealt with is heavier. Although our group are aware of the need for safe sex, in the coming year we plan to organise information sessions with the boys and girls in separate groups, with a male nurse for the boys and a midwife for the girls. We thereby hope to consolidate their knowledge and to offer them a new focus for expression on the subject. As yet, we have not attempted to gather specific information on whether any of them are actively practising safe sex (use of condoms), mostly because of their relatively young age and immaturity. In the years to come and during the course of their development, we will be able to learn, little by little, how their lives and sexual relationships are shaped vis-à-vis their present difficulties and with the psychological support that we have been able to provide to them.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the children and mothers in the Programme Enfant Yopougon and the social medicine team. This research was conducted with the support of the Agence Nationale de Recherches sur le Sida through its coordinated action 1277/1278. Our thanks to Becky Rubine, who translated the text and our revisions from French into English.

Notes

* All names are pseudonyms.

References

- ONUSIDA. Rapport sur l'épidémie mondiale de VIH/SIDA. 2002; ONUSIDA: Geneva, 26F.

- H Aka Dago-Akribi. Rôle du psychologue clinicien dans la prise en charge et la lutte contre le VIH/SIDA. Revue Ivoirienne des Lettres et Sciences Humaines. 5: 2003; 5–21.

- LK Brown, KJ Lourie. Children and adolescents living with HIV and AIDS: a review. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 41(1): 2000; 81–96.

- ONUSIDA. Les enfants au bord du gouffre. HRN-C-00-99-00005-00. 2002; 36.

- R Nduati, W Kiai. Communicating with adolescents on HIV/AIDS in East and Southern Africa. 1996; Regal Press Kenya: Nairobi.

- I Funck-Brentano. Enjeux psychologiques. L'infection à VIH de la mère et de l'enfant. 1998; Médecine-Sciences Flammarion: Paris, 256–278.

- G Foster, J Williamson. A review of the impact of HIV/AIDS on children in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS. 14(Suppl.3): 2000; S275–S284.

- F Dolto. L'image inconsciente du corps. 1984; Seuil, La Couleur des Idées: Paris, 379.

- D Sibony. Entre-Deux. L'origine en partage. 1991; Seuil, La Couleur des Idées: Paris, 399.

- AC Dumaret, N Boucher, D Rosset. Aspects psycho-sociaux et dynamiques familiales. 1995; INSERM: Paris, 157.

- S Freud. Trois essais sur la théorie de la sexualité. 1949; Gallimard-NRF: Paris.

- I Celérier. Adolescents séropositifs: le difficile apprentissage de l'autonomie. Transcriptase. 82: 2000; 23–25.

- A Collette. Introduction à la psychologie dynamique. 1990; éd de l'Université de Bruxelles: Bruxelles, 267.

- I Funck-Brentano. Troubles psychiatriques des enfants infectés par le virus d'immunodéficience humaine (VIH). Enc. Med. Chirur. Pédiatrie. 4-102-C-200: 1998; 1–8.

- J Nicolas, VIH Enfants. et Sida: quelle qualité de vie?. 1999; INSERM: Paris, 250.

- DJ Nasio. Enseignements de 7 concepts cruciaux de la psychoanalyse. 1988; éd Rivages: Paris, 267.

- UNICEF. Les orphelins du Sida. Réponses de la ligne de front en Afrique de l'Est et en Afrique Australe. UNICEF/C-110-8. 1999; Andrew: New York, 36.