Abstract

There are at least 83 countries where homosexuality is condemned in the criminal code; 26 of these are Muslim countries and in seven the death penalty for persons presumed guilty of homosexual acts makes sexual minorities extremely vulnerable. In spite of such obstacles, same-sex relationships do take place, even in the most repressive countries. Sometimes the very segregation of the sexes allows for intimacy between people of the same sex without it being considered abnormal. There are positive examples of same-sex relationships to be found in different Muslim cultures, e.g. in travelling theatre and musical groups and in poetry. Controversy regarding the position of Islam on homosexuality is ongoing, as the Qur'an is far from clear on the issue. There is also a strong connection between homophobic assaults by fundamentalists and those directed against women who do not “behave”. Sexuality and sexual conformity may be the focus of attention by fundamentalist forces because individual choice and autonomy, especially for women, is seen as a threat. Despite a threatening environment, sexual minorities are organising and becoming more visible in Muslim countries and communities; whether mainly political, social or religious in their motivation, these organisations all aim at breaking the isolation faced by sexual minorities.

Résumé

Dans au moins 83 pays, dont 26 pays musulmans, l'homosexualité est punie par le droit pénal ; dans sept d'entre eux, la peine capitale prévue pour les présumés coupables d'actes homosexuels rend les minorités sexuelles extrêmement vulnérables. Malgré ces obstacles, des personnes du même sexe ont des relations, même dans les pays les plus répressifs. Parfois, la ségrégation sexuelle autorise une intimité entre personnes du même sexe sans qu'elle soit considérée anormale. On trouve de nombreux exemples positifs de relations homosexuelles dans différentes cultures musulmanes, par exemple dans le théâtre ambulant, les groupes musicaux et la poésie. La controverse sur la position de l'Islam sur l'homosexualité se poursuit, car le Coran est loin d'être clair sur la question. Il existe également une forte relation entre les violences homophobes de fondamentalistes et celles qui frappent les femmes qui « se conduisent mal ». Si les fondamentalistes s'intéressent à la sexualité et à la conformité sexuelle c'est peut-être qu'ils considèrent le choix individuel et l'autonomie, particulièrement pour les femmes, comme une menace. En dépit des risques, les minorités sexuelles s'organisent et deviennent plus visibles dans les communautés et les pays musulmans; que leur motivation soit principalement politique, sociale ou religieuse, ces organisations visent toutes à rompre l'isolement des minorités sexuelles.

Resumen

La homosexualidad es condenada en el código penal de por lo menos 83 paı́ses, entre ellos 26 paı́ses musulmanes. En siete de estos paı́ses, la pena de muerte para personas supuestamente culpables de actos homosexuales hace muy vulnerables las minorı́as sexuales. A pesar de dichos obstáculos, las relaciones entre personas del mismo sexo sı́ ocurren, hasta en los paı́ses más represivos. A veces la segregación de los sexos permite relaciones ı́ntimas entre personas del mismo sexo sin que se considere anormal. Existen muchos ejemplos positivos de relaciones entre personas del mismo sexo en diferentes culturas musulmanas, como por ejemplo en el teatro itinerante, en grupos musicales y en la poesı́a. Hay una controversia permanente acerca de la postura del Islam hacia la homosexualidad, ya que el Corán es poco claro al respecto. Hay además un vı́nculo fuerte entre los asaltos homofóbicos por fundamentalistas y los asaltos a las mujeres que “no se comportan bien”. La sexualidad y la conformidad sexual posiblemente atraen la atención de las fuerzas fundamentalistas porque la opción y la autonomı́a, especialmente de las mujeres, se perciben como una amenaza. A pesar del ambiente amenazante, las minorı́as sexuales están organizándose y haciéndose más visibles en los paı́ses y comunidades musulmanes. Todas estas organizaciones –sea su motivación polı́tica, social o religiosa—pretenden romper el aislamiento enfrentado por dichas minorı́as.

I was born and raised in Algiers, of a French father and an Algerian mother. Having access to both cultures made me realize early on that racism as well as sexism were all pervasive on both sides of the Mediterranean. It took me a few more years to come to the conclusion that homophobia was just as widespread.

Amnesty International counts at least 83 countries where homosexuality is explicitly condemned in the criminal code; 26 of these are Muslim.Footnote* This means that the majority of Muslim countries, including supposedly “liberal” ones like Tunisia as well as dictatorships like Sudan, outlaw same-sex relationships.

The seven countries in the world that carry the death penalty for persons presumed guilty of homosexual acts, justify this punishment with the shari'a—or standard interpretation of Muslim jurisprudence. Though not always applied, the existence of the death penalty makes sexual minorities extremely vulnerable.

The state is not alone in practicing repression. Communities and families have a part to play. In the Philippines, for example, in 1998 “Muslim militia” launched an anti-gay campaign on the island of Mindanao during which gay Muslims were terrorized, beaten up, and ordered to leave or be castrated.

Jordan does not specifically outlaw homosexuality either. But that did not stop four Jordanians last year trying to kidnap their 23-year-old lesbian relative studying in the US, beating her and attempting to force her onto a plane bound for Jordan. The police acted promptly and came to her rescue, but such an outcome tends to be the exception rather than the rule. Violence, harassment, persecution and extra-judicial or “shame” killings are not uncommon.

Sex and tradition

In spite of such obstacles and hostility, same-sex relationships do take place, even in the most repressive countries. As one researcher on the Gulf told a Pan Arab Conference on Sexuality, held in Oxford in June 2000: “In prison same-sex sex is the norm. Saudi Arabia is just a large prison.”

Sometimes, the very segregation of the sexes allows for intimacy between people of the same sex without it being considered abnormal. As long as one keeps a low profile, such behaviour may generally go unchallenged. This is true for both sexes. For women, cultural patterns may allow particular opportunities for intimacy: it is fairly acceptable to share a bed with your female cousin, your best friend and so on. And traditional women-only ceremonies may actually enable rural lesbians to make regular contact with other women.

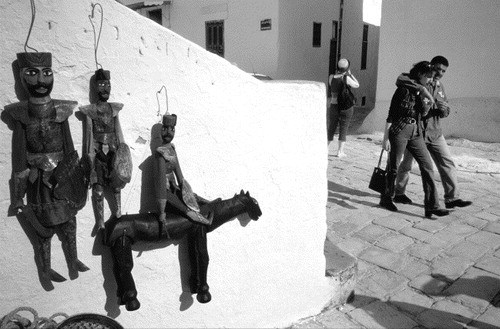

Culture is not, therefore, always against us and there are positive examples of same-sex relationships to be found in different Muslim cultures. Nor is invisibility always required. For example, in some traditional travelling theatres and musical groups in Pakistan, the younger men who play female roles sometimes live as a couple with the group leader. Among such communities, male couples may live love relationships quite openly. There is also an entire body of poetry in local and Urdu literature that is clearly based on male love, yaari.Footnote*

Positive as they are, such examples should not make us forget that homophobia is prevalent, as well as systematically promoted by conservative forces, everywhere.

Conservative manipulation

“The Qur'an clearly states that homosexuality is unjust, unnatural, a transgression, ignorant, criminal and corrupt,” declares the Jamaat-e-Islami, an extreme right politico-religious party in Pakistan.

In fact, the Qur'an is far from clear on the issue and the controversy regarding the position of Islam and homosexuality is ongoing. For some people, homosexuality is “unlawful” in Islam; for others, the Qu'ran does not clearly condemn homosexual acts.Footnote*

The only actual reference to homosexuality in the Qur'an can be found in the sections about Sodom and Gomorrah. While the harsh punishment inflicted on the people of Sodom and Gomorrah at the time of the prophet Lut is for some people a clear proof that Allah meant to eradicate homosexual practice, others argue that there is no specific punishment for homosexuality. The people of Sodom were punished for “doing everything excessively” and for not respecting the rules of hospitality. They insist that it is not the Qur'an itself that brings condemnation of homosexuals but rather the homophobic culture prevailing in Muslim societies.

In the Women Living Under Muslim Laws Network,Footnote† to which I belong, we maintain that “fundamentalism” is not a return to the “fundamentals” of any given religion; “fundamentalists” are extreme-right political forces seeking to obtain or maintain political power through manipulation of religion and religious beliefs, as well as other ethnic, culturally-based identities. And the rise of “fundamentalism” is a global phenomenon which affects not just Islam but all major religions.

There is also a strong connection between fundamentalist homophobic assaults and those directed against women who do not “behave”, who may be unmarried or living alone. Extremist religious leaders and their followers target sexual minorities and women first. They focus their offensive against homosexuals as well as others who transgress boundaries of “acceptable” behaviour. The very same rhetoric is used to justify repression against homosexuals, feminists or “different” women who all are systematically denounced as non-Muslim, non-indigenous and so forth. It is always through manipulation of religious, national or cultural identities that violence is legitimised.

Both extremist religious leaders and state officials are likely to demonise sexual minorities, often as a means to distract from economic crisis or political controversy. Indeed, incitement to hatred and manifestations of homophobia increase in places where the local political agenda is most affected by growing fundamentalist forces.

For example, one of the very first victims of Algerian fundamentalists was Jean Sénac, a gay poet assassinated in the early 1980s. Also in Algeria, Oum Ali, an unmarried woman living alone with her children in the Southern town of Ouargla, was stoned and her house burned down in 1989, killing her youngest son. These two incidents occurred long before the “official” beginning of the conflict; they reveal the untruth of Algerian fundamentalists' claims that they only resorted to violence in 1992 after being robbed of victory by the Government's cancellation of elections. In fact they targeted both homosexuals and women earlier on, but there was hardly anyone to stand up for such “second class victims”.

Why sexuality?

Why are sexuality and sexual conformity the focus of so much attention by fundamentalist forces? A possible answer is that people making individual choices appear as a challenge: autonomy, especially for women, is seen as a threat.

It is interesting to note that in past centuries Arabs attributed homosexual behaviour to the bad influence of Persians. Today, it is much the same story, though the characters may change. In June 2000, Malaysian Foreign Minister Syed Hamid Albar stated that homosexuality was “against nature” and, following a call by Human Rights Watch to ban Malaysia's sodomy law, insisted, “We can't amend the country's laws merely due to calls by outsiders.”

Not just a local or national phenomenon, fundamentalism has taken on a global dimension. Extremist religious leaders from various faiths are coming together to oppose sexual rights. By “closing ranks”, coalitions of Christians, Muslims and other fundamentalists affect the international agenda. We saw the effect of such alliances on women's reproductive rights at the Cairo Conference on Population and Development in 1994. Such alliances also blocked the recognition of the rights of lesbians at both the 1995 World Conference on Women held in Beijing and the review of the Beijing Platform for Action in June 2000.

Of course, similar coalitions influence local political agendas. Take Great Britain, a secular country with a very vocal extremist Muslim minority. A Muslim–Christian alliance was recently formed to oppose the repeal of Section 28, a law introduced in 1988 which forbids the “promotion” of homosexuality in schools as “a pretended family relationship”. At a conference in May 2000, religious spokesperson Dr Majid Katme stated that “lesbianism is spreading like fire in society. We must vaccinate our children against this curse”. He is supported in this view by Sheikh Sharkhawy, a senior cleric at the prestigious Regent's Park mosque in central London, who publicly advocates the execution of gay males over the age of 10 and life imprisonment for lesbians.

At least as worrying is the support for fundamentalist politics by the so-called “free West”. The help extended by states pretending to defend democracy is not a new phenomenon. Imam Khomeiny was resident in France for several months in 1978, just before going back to Iran to lead the “Islamic” revolution. In Afghanistan, the CIA not only trained the Taliban but has also “admitted bringing 25,000 Arab volunteers to fight against the Red Army”. Incidentally, both these countries, Iran and Afghanistan, currently sentence homosexuals to death.

What does that teach us? First, that the hypocrisy of most political leaders knows no limit: their ever-changing definition of “fundamentalism” allows them to turn against their allies of yesterday who, if guided by moral values, they should never have got involved with in the first place. Second, it is obvious that economic and geo-strategic concerns will always prevail. We can only regret that there are so few allies at the international level who are ready to compromise their interests in order to defend the rights of women and sexual minorities.

Strategies of resistance

Despite a threatening environment, sexual minorities are organising and becoming more visible in Muslim countries and communities. For example, much research is being carried out to interpret religious texts. The Qu'ran is being re-examined by gay, or gay-friendly, theologians and believers in order to break the monopoly of male homophobic interpretation. To counter the stereotype of homosexuality as foreign, others are engaged in reclaiming homoerotic literature.

Another positive example is found in Lebanon, where homosexuality is illegal, but a popular weekly TV programme (Al Shater Yahki) has been focusing on sexuality since 1997 and includes gay voices. The fact that they speak from behind masks gives a measure of the risks involved.

Nevertheless, new solidarity associations are being set up. These organisations are, for obvious security reasons, often located outside Muslim countries and communities. Most of them, however, connect with either individuals or groups within Muslim countries. Whether mainly political, social or religious in their motivation these organisations all aim at breaking the isolation faced by sexual minorities. In Muslim countries and communities, sexual minorities have only just begun. Threats of violence and accusations of betraying one's culture and religion have discouraged many from taking a public stand. However, more and more people are rejecting the idea that violence against sexual diversity is “divinely sanctioned”.

Acknowledgements

This article is based on a talk presented at the International Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Conference, Rome, 3 July 2000, on “The Separation of Faith and Hate: Sexual Diversity, Religious Intolerance and Strategies for Change” World Pride. It is reprinted with kind permission from WLUML and New Internationalist, No.328, October 2000 (〈www.newint.org〉). It was nominated as best feature article of the year by Huriyah (Arabic for freedom), a magazine for queer Muslims worldwide.

Notes

* The 26 countries Muslim countries that condemn homosexuality are: Afghanistan, Algeria, Bahrain, Bangladesh, Bosnia, Iran, Jordan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgystan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Malaysia, Mauritania, Morocco, Oman, Pakistan, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, Syria, Tajikistan, Tunisia, Turkmenistan, United Arab Emirates and Yemen. According to the winter 2000 issue of Outfront, the newsletter of Amnesty International's Programme on Human Rights and Sexual Identity, the number of predominantly Muslim countries in which homosexuality is “officially criminalised” is as high as 34.

* Examples of poetry celebrating male love include Sufi poets such as Jalaluddin Rumi about his lover Shams-e-Tabriz and the Ottoman “divan literature” by male poets celebrating their male lovers. Also, feminists in Bangladesh recently reprinted “Sultana's dream” and WLUML reprinted a novel by Indian author Ismat Chughtal.

* The main schools of thought within Islam differ in their treatment of homosexuals: for example, the Hana'ite school (to be found mainly in South and East Asia) does not advocate physical punishment while the Hanabalites (prevalent in the Arab world) call for a severe punishment; the Sha'fi school (also seen in the Arab world) makes it very difficult to actually prove homosexual acts (a minimum of four male direct witnesses is required).

† Women Living Under Muslim Laws is a network of women whose lives are shaped, conditioned or governed by laws, both written and unwritten, drawn from interpretation of the Koran tied up with local traditions. While the imposed rules defining the identity of women living in Muslim countries and communities vary according to sect, culture, ethnicity and class, they share one common ground: all embody and promote patriarchal structures and values.